USHMM Finding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Guide to Holocaust-Related Holdings at Library and Archives Canada

Research guide to Holocaust-related holdings at Library and Archives Canada August 2013 Library and Archives Canada Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 4 LAC’S MANDATE ..................................................................................................... 5 CONDUCTING RESEARCH AT LAC ............................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE ........................................................................................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE LAC’S ONLINE SEARCH TOOLS ......................................................................................................... 5 LANGUAGE OF MATERIAL.......................................................................................................................................... 6 ACCESS CONDITIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Government of Canada records ................................................................................................................ 7 Private records ................................................................................................................................................ 7 NAZI PERSECUTION OF THE JEWISH BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR............... 7 GOVERNMENT AND PRIME MINISTERIAL RECORDS................................................................................................ -

Holocaust Fiction/Non-Fiction

Holocaust Fiction/Non-Fiction Sorted by Call Number / Author. 341.4 ALT Altman, Linda Jacobs. Impact of the Holocaust. Berkeley Heights, N.J. : Enslow Publishers, 2004. This book discusses the urgency to establish a Jewish homeland and the need for a worldwide human rights policy. 362.87 AXE Axelrod, Toby. Rescuers defying the Nazis : non-Jewish teens who rescued Jews. New York : Rosen Publishing, 1998. This book relates the stories of courageous non-Jewish teenagers who rescued Jews from the Nazis. 741.5 HEU Heuvel, Eric, 1960-. A family secret. 1st American ed. New York : Farrar Straus Giroux, 2009. While searching his Dutch grandmother's attic for yard sale items, Jeroen finds a scrapbook which leads Gran to tell of her experiences as a girl living in Amsterdam during the Holocaust, when her father was a Nazi sympathizer and Esther, her Jewish best friend, disappeared. In graphic novel format. 741.5 HEU Heuvel, Eric, 1960-. The search. 1st American ed. New York : Farrar, Straus, Giroux Books, 2009. After recounting her experience as a Jewish girl living in Amsterdam during the Holocaust, Esther, helped by her grandson, embarks on a search to discover what happened to her parents before they died in a concentration camp. 920 AYE Ayer, Eleanor H. Parallel journeys. 1st Aladdin Paperbacks ed. New York : Aladdin Paperbacks, 2000, c1995. An account of World War II in Germany as told from the viewpoints of a former Nazi soldier and a Jewish Holocaust survivor. 920 GRE Greenfeld, Howard. After the Holocaust. 1st ed. New York : Greenwillow Books, c2001. Tells the stories of eight young survivors of the Holocaust, focusing on their experiences after the war, and includes excerpts from interviews, and personal and archival photographs. -

Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland During World War II1

July 2008 Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland during World War II1 Mark Paul Collaboration with the Germans in occupied Poland is a topic that has not been adequately explored by historians.2 Holocaust literature has dwelled almost exclusively on the conduct of Poles toward Jews and has often arrived at sweeping and unjustified conclusions. At the same time, with a few notable exceptions such as Isaiah Trunk3 and Raul Hilberg,4 whose findings confirmed what Hannah Arendt had written about 1 This is a much expanded work in progress which builds on a brief overview that appeared in the collective work The Story of Two Shtetls, Brańsk and Ejszyszki: An Overview of Polish-Jewish Relations in Northeastern Poland during World War II (Toronto and Chicago: The Polish Educational Foundation in North America, 1998), Part Two, 231–40. The examples cited are far from exhaustive and represent only a selection of documentary sources in the author’s possession. 2 Tadeusz Piotrowski has done some pioneering work in this area in his Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces, and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998). Chapters 3 and 4 of this important study deal with Jewish and Polish collaboration respectively. Piotrowski’s methodology, which looks at the behaviour of the various nationalities inhabiting interwar Poland, rather than focusing on just one of them of the isolation, provides context that is sorely lacking in other works. For an earlier treatment see Richard C. Lukas, The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation, 1939–1944 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986), chapter 4. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Archives United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives: Record Group 02, “Survivor Testimonies” Baumrin, Zvi. “A Short Autobiography.” RG-02.145; Acc. 1994.A.0143. Beer, Susan. “To Auschwitz and Back: An Odyssey.” RG-02*144; Acc. 1994.A.073. Berman, Gizel. “The Three Lives of Gizel Berman.” RG-02.157; Acc. 1994.A.0235. Bohm, Rose Eizikovic. “Remember Never to Forget Memoir.” RG-02.207; Acc. 1996. A.333. Büchler, Jehoshua Robert. “The Expulsion Testimony.” RG-02.102 (1994.A.160). Ferera, Rosa. RG-02.002*11; Acc. 1991.A.0089. Feuer, Katarina Bloch. “Diary Nearly 50 Years Later.” RG-02.209; Acc. 1994.A.150. Gross, Eva. “Prisoner 409.” RG-02.111; Acc. 1994.A.202. Gundel, Kay. “Reborn: Memoirs of a Camp Survivor, 1947–1986.” RG-02.004*01; Acc. 1986.019. Herstik, Rose. RG-02.002*03. Hilton, Rita Kerner. “My Story.” RG-02.164; Acc. 1994.A.0274. Hoffman, Regina Godinger. “A Void in My Heart.” RG-02.152; Acc. 1994.A.0237. Kahn, Regina. RG-02.002*04; Acc. 1991.A.0089. Kalman, Judith. RG-02.002*10. Krausz, Anna Heyden. RG-02.002*10. Machtinger, Sophie. “Recollections from My Life’s Experiences.” Trans. Douglas Kouril. RG-02.012*01. Pollak, Zofia. RG-02.002*22. Rajchman, Chiel M. RG-02.137; Acc. 1994.A.138. Sachs, Gisela Adamski. “Unpublished Testimony.” RG-02.002*08. Spiegel, Pearl. RG-02.002*04; Acc. 1991.A.0089. Weisberger, Madga Willinger. “I Shall Never Forget.” RG-02.002*05. Zavatzky, Jenny. RG-02.002*27; Acc. -

16 Freuen in Di Ghettos: Leib Spizman, Ed

Noten INLEIDING: STRIJDBIJLEN 16 Freuen in di Ghettos: Leib Spizman, ed. Women in the Ghettos (New York: Pioneer Women’s Organization, 1946). Women in the Ghettos is a compilation of recollections, letters, and poems by and about Jewish women resisters, mainly from the Polish Labor Zionist movement, and includes excerpts of longer works. The text is in Yiddish and is intended for American Jews, though much of its content was originally published in Hebrew. The editor, Leib Spizman, escaped occupied Poland for Japan and then New York, where he became a historian of Labor Zionism. 18 Wat als Joodse verzetsdaad ‘telt’: For discussion on the definition of “resistance,” see, for instance: Brana Gurewitsch, ed. Mothers, Sisters, Resisters: Oral Histories of Women Who Survived the Holocaust (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998), 221–22; Yehudit Kol- Inbar, “ ‘Not Even for Three Lines in History’: Jewish Women Underground Members and Partisans During the Holocaust,” in A Companion to Women’s Military History, ed. Barton Hacker and Margaret Vining (Leiden, Neth.: Brill, 2012), 513–46; Yitchak Mais, “Jewish Life in the Shadow of Destruction,” and Eva Fogelman, “On Blaming the Victim,” in Daring to Resist: Jewish Defiance in the Holocaust, ed. Yitzchak Mais (New York: Museum of Jewish Heritage, 2007), exhibition catalogue, 18–25 and 134–37; Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman, “Resistance and Rescue,” in Women in the Holocaust, ed. Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 171–74; Gunnar S. Paulsson, Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw 1940–1945 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 7–15; Joan Ringelheim, “Women and the Holocaust: A Reconsideration of Research,” in Different Voices: Women and the Holocaust, ed. -

Thématiques Dans Les Récits Des Enfants Cachés Dans L'univers Catholique En France

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-17-2014 12:00 AM Thématiques dans les récits des enfants cachés dans l'univers catholique en France Carmen P. McCarron The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Alain Goldschläger The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in French A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Carmen P. McCarron 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McCarron, Carmen P., "Thématiques dans les récits des enfants cachés dans l'univers catholique en France" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2595. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2595 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THÉMATIQUES DANS LES RÉCITS DES ENFANTS CACHÉS DANS L’UNIVERS CATHOLIQUE EN FRANCE (Thesis format : Monograph) by Carmen McCarron Graduate Program in French Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada Carmen McCarron, 2014 Résumé Cette thèse examine des thématiques communes à une vingtaine de récits publiés en français par des enfants de la Shoah qui ont été cachés dans des familles et des institutions catholiques, surtout en France. La bibliographie étendue de l’Institut de recherche sur la littérature de l’Holocauste nous a donné la possibilité de rassembler et d’étudier ces textes en un corpus cohérent, pour la première fois. -

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion

Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion STUDY GUIDE Produced by the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme in partnership with the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education and Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority asdf United Nations “JEWISH WOMEN PERFORMED TRULY HEROIC DEEDS DURING THE HOLOCAUST. They faced unthinkable peril and upheaval — traditions upended, spouses sent to the death camps, they themselves torn from their roles as caregivers and pushed into the workforce, there to be humiliated and abused. In the face of danger and atrocity, they bravely joined the resistance, smuggled food into the ghettos and made wrenching sacrifices to keep their children alive. Their courage and compassion continue to inspire us to this day”. BAN KI-MOON, UNITED NATIONS SECRETARY-GENERAL 27 January 2011 Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion Women and the Holocaust: Courage and Compassion STUDY GUIDE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following individuals who contributed to this project: Na’ama Shik, Yehudit Inbar, Dorit Novak, Stephen D. Smith, Ita Gordon, Irena Steinfeldt, Jonathan Clapsaddle, Liz Elsby, Sheryl Ochayon, Yael G. Weinstock, Inbal Eshed, Olga Yatskevitch, Melanie Prud’homme, Amanda Kennedy Zolan, Allan Markman, Matias Delfino and Ziad Al-Kadri. Editor: Kimberly Mann © United Nations, 2011 Historical photos provided courtesy of Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, all rights reserved. For additional educational resources, please see www.yadvashem.org. Images and testimony of participating survivors provided courtesy of the USC Shoah Foun- dation Institute for Visual History and Education, all rights reserved. For more information on the Shoah Foundation Institute, please visit www.usc.edu/vhi. -

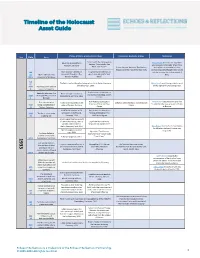

Timeline of the Holocaust Asset Guide

Timeline of the Holocaust Asset Guide Photos, Artifacts, & Instructional Videos Documents, Handouts, & Maps Testimonies Year Date Entry Stickers with Nazi propaganda Hindenburg and Hitler in Harry Hankin describes the day Hitler slogans: "One People, One Potsdam, Germany was appointed Chancellor of Germany Reich, One Fuhrer" Echoes Student Handout: The Weimar and reflects on the belief of older Republic and the Rise of the Nazi Party German Jews who thought Hitler would JAN Key Historical Concepts in A sign calling on Germans to only be in power for a short period of 30- Adolf Hitler becomes Holocaust Education: The greet each other with "Heil time. FEB 1 chancellor of Germany Weimar Republic Hitler" FEB The Reichstag building after being set on fire in Berlin, Germany, Henry Small recalls being called to work 27- on February 27, 1933 on the night of the Reichstag arson. MAR Reichstag arson leads to 5 state of emergency Graph: results of elections to Reichstag elections: the Hitler voting in elections at the German Reichstag, March MAR Nazis gain 44 percent of Koenigsberg, Germany, 1933 5, 1933 5 the vote Key Historical Concepts in Herbert Kahn describes why and how First concentration A view of the barracks in the Echoes Student Handout: Concentration Holocaust Education: Nazi his older brother was arrested and sent MAR camp is established in camp of Dachau, Germany Camps 22 Dachau, Germany Camps to Dachau. Adolf Hitler watches an SA Key Historical Concepts in MAR The Nazis sponsor the procession in Dortmund, Holocaust Education: The 24 Enabling Act Germany, 1933 Totalitarian Regime A man supporting the boycott of Jewish businesses, next to Sign from Nazi Germany: a Jewish-owned store in "Jews are not wanted here" Berlin, Germany, April 1933 Otto Hertz remembers the humiliation he felt when his family's store was Nazi propaganda, boycott boycotted. -

Chapter 1. a Holocaust in Trains (Introduction)

– Chapter 1 – INTRODUCTION A Hidden Holocaust in Trains “Move over. Make room for the others!” We squeezed and crushed in as if we were animals. A man with only one leg cried out in agony and his horrifi ed wife pleaded with us not to press against him. We traveled in the dark crush for a long, long time. No air. No food. People urinating continuously in the latrines. Then the shriek. Over the moans and helpless little cries, there rose a piercing scream I shall never forget. From a woman on the fl oor beneath the small, barred window came the horrifying scream. She held her head in both her hands and then we who were close by saw the words scratched in tiny letters: “last transport went to Auschwitz.”1 When we were marched out to the cattle trains, you have a cattle train in the Washington museum, I never really knew what the dimensions were, nobody could tell me, it’s about three quarters the size of a regular tour bus … there were about 170 people packed into this cattle car. At fi rst some people wanted to pre- vent the panic, to tell people, “look people, organize, stand up, there is no room for everyone to sit” … but it didn’t work, people were in a panic, the young and strong were standing at the windows, blocking whatever air there was.2 Even today freight cars give me bad vibes. It is customary to call them cattle cars, as if the proper way to transport animals is by terrorizing and overcrowd- ing them. -

Teaching Night

Teaching NIGHTCreated to accompany the memoir by Elie Wiesel Teaching NIGHT Created to accompany the memoir by Elie Wiesel Facing History and Ourselves is an international educational and professional devel- opment organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote the devel- opment of a more humane and informed citizenry. By studying the historical devel- opment of the Holocaust and other examples of genocide, students make the essential connection between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives. For more information about Facing History and Ourselves, please visit our website at www.facinghistory.org. Copyright © 2017 by Facing History and Ourselves, Inc. All rights reserved. Facing History and Ourselves® is a trademark registered in the US Patent & Trademark Office. ISBN: 978-1-940457-23-9 CONTENTS Using This Study Guide 1 Exploring the Central Question 1 Section Elements 2 Supporting the Memoir with Historical Context 2 Helping Students Process Emotionally Powerful Material 3 Section 1 Pre-Reading: The Individual and Society 5 Overview 5 Introducing the Central Question 5 Activities for Deeper Understanding 6 Map: Eliezer’s Forced Journey 9 Reading: Elie Wiesel’s Childhood 10 Visual Essay: Pre-War Sighet 12 Section 2 Introducing NIGHT 21 Overview 21 Exploring the Text 22 Connecting to Central Question 22 Activities for Deeper Understanding 22 Handout: Identity Timeline 24 Reading: The Holocaust in Hungary 25 Handout: Iceberg Diagram 27 Reading: The Difference between Knowing and Believing 28 Section 3 Separation and Deportation 31 Overview 31 Exploring the Text 31 Connecting to the Central Question 32 Activities for Deeper Understanding 32 Reading: Universe of Obligation 37 Handout: Universe of Obligation 39 Reading: Witnesses, Bystanders, and Beneficiaries in Hungary 40 Handout: Night and Day 42 Handout: Found Poem: Mrs. -

© Copyright by Anna Marie Anderson May, 2013

© Copyright by Anna Marie Anderson May, 2013 JEWISH WOMEN IN THE CONCENTRATION CAMPS: PHYSICAL, MORAL, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL RESISTANCE ________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston ________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _______________ By Anna Marie Anderson May, 2013 JEWISH WOMEN IN THE CONCENTRATION CAMPS: PHYSICAL, MORAL, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL RESISTANCE ______________________ Anna Marie Anderson APPROVED: ______________________ Sarah Fishman, Ph.D. Committee Chair ______________________ Nancy Beck Young, Ph.D. ______________________ Irene Guenther, Ph.D. _______________________ John W. Roberts, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of English JEWISH WOMEN IN THE CONCENTRATION CAMPS: PHYSICAL, MORAL, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL RESISTANCE ________________ An Abstract of a Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston ________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _______________ By Anna Marie Anderson May, 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the methods of resistance used by Jewish women in the concentration camps. These women based their resistance on their pre-camp experiences, having learned valuable skills during the economic crises and violent anti-Semitism of the 1920s to 1930s. This study demonstrates that Jewish women had to rely on alternative forms of resistance—such as the formation of “camp families,” saving food, repairing clothing, and personal hygiene—in order to survive the camps. This work relies on survivor testimonies and memoirs. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Sarah Fishman, whose guidance enabled me to develop this thesis. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. -

Women's Resistance Through Testimony Astudy Of

Faculty of Arts Department of Cultural Sciences WOMEN’S RESISTANCE THROUGH TESTIMONY – A STUDY OF SURVIVORS’ TALES FROM THE HOLOCAUST Master’s Thesis in Gendering Practices, 30 hec Author: Katarina Tullia von Sydow Supervisor: Katarina Leppänen Spring 2015 Abstract This thesis analyses Jewish women Holocaust survivor’s testimonies. The purpose is to investigate what events the women tell of, how they tell of the choice and act of giving testimony, and to analyse whether resistance is manifest in their stories. I offer an interpretation with a feminist and intersectional historical outlook through the use of oral history as method and collective memory as an overarching framework. Common gender essentialist readings of women’s survivor stories from the Holocaust are enhancements of the "heroine" aspect of the characters that emerge in survivor testimonies, and the diminution of character aspects that do not correspond with preconceived gender roles. By further reinforcing epithets such as “heroine”, there is a risk of withholding complex readings. In taking use of Avery Gordon’s concept of complex personhood and Joan W. Scott and Judith Butlers understandings of gender as a useful category of historical analysis, I attempt to avoid essentialism and further a feminist analysis of women’s testimonies from the Holocaust. I argue that the actual acts the women tell of, in addition to the telling of the stories themselves and how they speak of this, all serve as means of resistance. The result of the analysis is that the women’s testimonies together create a powerful collective memory, a collective solidarity, which seeks to make amends for, and thereby retroactively show resistance to what they endured, while also hindering oppression in the contemporary.