Can an Artificial Channel Help Save the Tuggerah Lakes?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gosford City Centre Masterplan the Gosford Challenge Gosford City Centre Masterplan

City, Our destiny Gosford City Centre Masterplan The Gosford ChallenGe Gosford City Centre Masterplan r City, u O destiny a World Class reGional Waterfront City r City, iii u O destiny The Gosford ChallenGe Gosford City Centre Masterplan acknowledgments JOINT PROJeCt SPONSORS DESIGn TEAM Gosford City Council land and property Gosford Challenge team Clr Chris Holstein Management authority Colleen Worthy-Jennings Mayor Hon Tony Kelly MHR Stephen Fairnham Clr Craig Doyle Warwick Watkins Duncan Clarke Deputy Mayor Graham Harding Helen Polkinghorne Clr Chris Burke Brett Phillips John Tilston Clr Peter Freewater Stewart Veitch Barbara Cruise Clr Amy Houston Robert Eyre Clr Terri Latella Scott Burton Clr Jim Macfadyen Steve Green Clr Laurie Maher Sue Verhoek Clr Vicki Scott Kerr Partnering Clr Jeff Strickson Cox Architects and Planners Peter Wilson Patrick Condon Stephen Glen Rob Lane Gary Chestnut Aurecon Rod Williams Arup Nic Pasternatsky Oculus Terry Thirlwell teaming with ideas r City, u O destiny Contents 1 GROWING A REGIONAL CITY 2 4 MAKING IT HAPPEN 92 1.1 gosford as a regional city 3 4.1 implementation plan 93 1.2 greater metropolitan context 4 4.2 the beginning - two priority areas 96 1.3 regional context 5 APPENDICES 1.4 local context 6 appendix 1 sustainability 102 1.5 attributes of a regional city 8 appendix 2 regional benchmarks 110 1.6 purpose of a masterplan 10 appendix 3 retail and commercial market 114 1.7 the journey 12 appendix 4 participants 116 1.8 planning context 14 1.9 key strategic opportunities 15 2 SPATIAL FRAMEWORK 16 2.1 the city framework 16 2.2 the masterplan 18 2.3 five precincts of activity 20 3 MASTERPLAN ELEMENTS 48 3.1 connecting places 50 3.2 activate the city 56 3.3 responsive built form 60 3.4 generate jobs and new enterprises 64 3.5 living in the city 72 3.6 access and movement 76 3.7 sustaining the city (enhancing the natural environment) 86 note: diagrams of future development are concept only. -

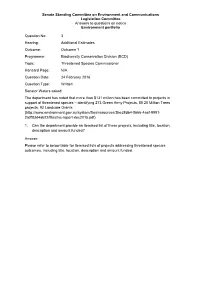

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Challenges of Saltmarsh Rehabilitation in a Non-Tidal Estuary – Perspectives on Delivery of On-Ground Works

CHALLENGES OF SALTMARSH REHABILITATION IN A NON-TIDAL ESTUARY – PERSPECTIVES ON DELIVERY OF ON-GROUND WORKS M Barnett, N Dixon, A Halcrow, S Tsaprounis, D Ryan Wyong Shire Council, Wyong NSW Background Saltmarshes are a unique component of coastal estuaries in Australia that exist at the land and water interface. Conditions in these areas are highly dynamic and biota must be adapted and specialised to cope with varying degrees of salinity, tidal inundation, competition and disturbance. Their unique position allows saltmarshes to function in several ways including flood and erosion control, storm surge buffering, water quality improvement and seagrass wrack assimilation. For these and many other reasons, not the least being biodiversity, saltmarshes need to be conserved as vital parts of the Australian coastline. Saltmarshes are a diminishing habitat in the coastal biosphere of Australia. New South Wales in particular has the least amount of coastal saltmarsh remaining of any state. Saltmarsh occurs along the entire coastline of NSW, but is generally limited to small patches that have been highly modified. In recognition of the decline and uniqueness of saltmarsh in NSW, it has been listed as an Endangered Ecological Community in NSW under the Threatened Species Conservation Act. On the local scale, it is believed that approximately 85% of the saltmarshes around Tuggerah Lakes have been destroyed, degraded or fragmented since European settlement. Saltmarsh recovery on rehabilitated sites can occur naturally, be assisted through active planting and/or bush regeneration or a combination of both. Natural recovery of saltmarsh communities occurs after disturbance via establishment of seedlings or vegetative expansion of remaining plants. -

Central Coast and Hawkesbury River Recreational Fishing Guide

Central Coast and Hawkesbury River Recreational Fishing Guide Fisheries Compliance Unit • fish aggregating devices (FADs) to enhance fishing for dolphinfish and even tuna and August 2020 marlin; Fishing is a fun, outdoor activity for the whole • creation of recreational fishing havens; family. Fishing rules help ensure healthy and sustainable fisheries for future generations. • angler facilities such as fish cleaning tables and fishing platforms; The Central Coast’s waterways provide excellent beach, rock, and boat fishing opportunities. This • stocking of freshwater fish in dams and rivers; guide provides essential information on fishing, • essential research on popular recreational fish including any closures and restrictions, which apply species; within the Central Coast district, extending from Munmorah State Recreation Park in the north, to • restoring important fish habitat; the southern bank of the Hawkesbury River. • marine stocking of prawns in estuaries; DPI fisheries officers routinely patrol waterways, • angler education and advisory programs such boat ramps and foreshores to advise anglers about as the Fishcare Volunteer program, fishing responsible fishing practices and to ensure workshops, Get Hooked…it's fun to fish compliance with NSW fishing regulations. primary schools education and fishing guides. Information on bag and size limits and legal fishing Much more information is available at gear can be obtained at www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries. www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries or by visiting your local DPI fisheries office. You can pay the NSW recreational fishing fee at www.onegov.nsw.gov.au or by calling 1300 369 To report suspected illegal fishing activity, call the 365 or at many outlets throughout NSW, such as Fishers Watch phone line on 1800 043 536 (free fishing tackle stores, caravan parks, local shops, call) or report on-line at service stations and many Kmart stores. -

Wyong Shire Council Submission in Response to the Central Coast Regional Plan

WYONG SHIRE COUNCIL SUBMISSION IN RESPONSE TO THE CENTRAL COAST REGIONAL PLAN SUBMISSION IN RESPONSE TO THE CENTRAL COAST REGIONAL PLAN 1 Wyong Shire Council Submission to the Draft Central Coast Regional Plan Date: March 2016 Version Final Date of Approval: 23 March 2016 © Wyong Shire Council Wyong Shire Council 2 Hely Street Wyong PO Box 20 Wyong NSW 2259 P 02 4350 5555 F 02 4351 2098 E [email protected] W www.wyong.nsw.gov.au Opening Hours 8.30am - 5.00pm Westfield Tuggerah 2 WYONG SHIRE COUNCIL CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 MAJOR PROJECTS 11 VISION 15 DELIVERING THE PLAN 17 GOAL 1 – ENHANCE COMMUNITY LIFESTYLES AND ACCELERATE HOUSING SUPPLY 20 GOAL 2 – GROW AND DIVERSIFY THE REGIONAL ECONOMY 30 GOAL 3 – SUSTAIN PRODUCTIVE LANDSCAPES 39 GOAL 4 – PROTECT AND MANAGE THE NATURAL AND CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT 40 GENERAL COMMENTS 43 CONCLUSION 45 A CONNECTED CENTRAL COAST MAP 47 Westfield Tuggerah SUBMISSION IN RESPONSE TO THE CENTRAL COAST REGIONAL PLAN 3 Wyong Shire Council has undertaken extensive planning in recognition of the expected population growth in the Central Coast region and has identified the need for additional infrastructure to support this growth and provide a foundation for development in this area. 4 WYONG SHIRE COUNCIL The Entrance EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document is Wyong Shire Council’s There has been significant growth in the (WSC) comprehensive response to the number of development applications ‘Draft Central Coast Regional Plan’ (Draft (DAs) lodged and approved in recent years CCRP). WSC supports the preparation of with 958 DA’s determined in 2014/15 with the Central Coast Regional Plan (CCRP) growth in residential development in the and its vision for the future of the region. -

The Corridor's Strengths

The Corridor’s strengths Wyong – a Town Centre with “good bones” Wyong Town Centre has many elements of a great regional centre, including an established fine grain street network with connections to a train station, Wyong River and open spaces. Home to the landmark Art House cultural facility, Council chambers and government agencies, Wyong is the cultural and civic Wyong River – a natural centrepiece core of the corridor. The character of Wyong Town Wyong River flows through the heart of the corridor, presenting as Centre is strengthened by a distinct heritage presence a natural centrepiece. Although access is constrained in some areas, and fine grain built form that line the high streets. the River is a significant asset, supporting an array of recreational activities including kayaking and fishing, as well as walking and cycle along the active transport links by the river foreshore. The River provides an important natural outlook for the surrounding urban Alison Street, Wyong areas. Tuggerah Lake, State Conservation Area (image: itsonlymylife163. blogspot) Natural Assets of Environmental Value The corridor is endowed with natural bushland precincts that provide environmental amenity to residents, workers and visitors. Tuggerah Nature Reserve features predominately untouched Wyong River from the Wyong Milk Factory bushlands and wetlands that have high conservation value, while the nearby Tuggerah State Conservation Area supports sustainable visitation and bushwalking. 26 DRAFT Tuggerah to Wyong Corridor Strategy Great local food, drink, arts and craft The Corridor features a growing number of exciting food, beverage, arts and craft offerings, building on growing interest in local and boutique products. There is a combination of restaurants, cafés, markets, function spaces and specialty stores in the area. -

Learning from the Past Research Project – Central Coast, NSW

Governance 21 Learning from the Past Research Project – Central Coast, NSW Rolf Fenner Australian Local Government Association Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT In 2003, the then Sustainable Ecosystems Division of the CSIRO was engaged by the Central Coast Region of NSW to undertake a detailed regional futures analysis based on a dynamic systems approach (Senge, 1992). A key component of such a research approach was the need to better understand and appreciate the historical context of previous regional planning policy initiatives. As a regional planning practitioner of several years experience, I was engaged by the CSIRO to undertake this “learning from the past” investigation. This paper summaries the value of such a research project by both examining the methodology adopted and findings arising from such an investigation. In short, the paper argues that as a consequence of reflecting on past policy experiences it is possible to better understand and appreciate what policy decisions were previously undertaken, and subsequently improve the opportunities for future policy decision making and implementation. A total of eighteen individuals were interviewed for the project. The regional participants chosen to be interviewed were a mixture of previous community leaders, politicians or senior professional bureaucrats. To encourage frank discussion and minimise any possibility of conflict of interests, all research participants at the time of interview were no longer in their substantive positions they once held. The process of identifying key individuals and relying on oral histories is not without methodological deficiencies. Whilst acknowledging these potential weaknesses, the project nevertheless was able to make a valuable contribution to regional planning on the Central Coast by identifying previous experiences and policy relationships as they related to matters of social, economic, environmental and local/ regional governance. -

Entrance Dynamics and Beach Condition at the Entrance and North Entrance Beaches

Wyong Shire Council Entrance Dynamics and Beach Condition at The Entrance and North Entrance Beaches April 2011 Entrance Dynamics and Beach Condition at The Entrance and North Entrance Beaches Prepared by Umwelt (Australia) Pty Limited on behalf of Wyong Council Project Director: Pam Dean-Jones Project Manager: Pam Dean-Jones Report No. 1869/RO5/Final Date: APRIL 2011 2/20 The Boulevarde PO Box 838 Toronto NSW 2283 Ph: 02 4950 5322 Fax: 02 4950 5737 Email: [email protected] Website: www.umwelt.com.au Entrance Dynamics Executive Summary Executive Summary This study was commissioned to provide further analysis of the sediment transport processes affecting sediment budget and coastal morphology at North Entrance Beach and The Entrance to Tuggerah Lake. The aim of the study was to clarify sediment transport linkages between The Entrance channel and North Entrance Beach and to identify and evaluate potential options for managing sedimentary processes in this dynamic coastal landscape, to reduce risks associated with coastal erosion hazards. North Entrance Beach lies at the southern end of the zeta curved Tuggerah coastal embayment. The southern extension of the beach is an intermittent spit and berm which forms at the mouth of the Tuggerah lake entrance channel. In historical times the mouth of the estuary closed for periods of up to three years. The sand deposits were scoured out of the entrance area by major flood flows. Since dredging of the outer entrance shoals commenced in 1993, the average channel width has declined compared to the average pre dredging condition. The range of channel conditions has also narrowed. -

Central Coast the Adams

The Adams Ultimate guide to business Map of the Central Coast .......................................................... 50 Demographics and other data .................................................... 51 Population ........................................................................... 51 Age profile ........................................................................... 52 Individual & Household income ........................................... 53 Educational attainments ....................................................... 54 Employed persons by Occupation ......................................... 54 Employed persons by Industry .............................................. 54 Distance table for Central Coast roads ................................. 56 Traffic Volume Data .............................................................. 56 Businesses operating on the Central Coast (number, size & turnover) ..................................................... 57 Climate data .............................................................................. 58 Contacts .................................................................................... 59 Local Government – Councillors and Senior Executives ......... 59 State Government – Representatives and Electorates ........... 60 Federal Government – Representatives and Electorates ........ 61 Other Government contacts ................................................. 62 Business Associations ................................................................. 63 Central Coast -

Map of the Proposed Federal Electoral Divisions of Charlton, Dobell

D R C a t t a i Martins Creek The Branch Dripstone C Clarence u d g Town e N T g E S G W W DUNGOG o r E k 149°30'E n 150°0'E o 150°30'E 151°0'E 151°30'E Paterson I w o R e g e r l e e A l e r Lue U W o iv C Q m R C I D Limeburners h N a R A b u M D Apple Tree r Creek r Lake Burrendong i e a S GOL iv K O Flat DE T C N R S M R r e e R E r e i N E o v G k HWY L G o e AN R r Bulga D N O Belford Pa E G R HWY t E Oakville e H Gosforth rs T Branxton o R R n Karuah Mumbil GREENWAY INSET O ive Balickera Y PACIFIC HW N r Channel North Seaham D Rothbury h Middle t R L Greta u D Dural O o MUSWELLBROOK S Nelson MACQUARIE Box Hill Riv MI Nelsons er D D N E Annangrove U M E NGL Windella Wallalong Plains R a W AND A cd T o w L na Lochinvar ld R e i l Lake H v PORT STEPHENS v W Bolwarra e e B RD Y r Y k L Windamere er W M e A t W n H i re u l C H PATERSON e Swan Bay C I C N R K W at C T ta Windeyer D E I IN i Hinton re Y C O D R MAITLAND Howes s H e W W S m M O k Hargraves C r SINGLETON Lagoon ia O N R R ive Broke l AD R l N Mount MAITLAND R i S i D D Kenthurst ve W R T Dee M r PATERSON Stuart L E u W Town ll R R e e Mulwee n O e E Four Mile Creek Duckenfield d Mallabula Cudgegong L y A T Grahamstown Cu M L Gillieston S C Oyster G d D re Rylstone g a O eg lo TE R Lake e H n N R o M Cove n g Pokolbin C Heights RA E Raymond k Rouse g E AYMOND CE D B R I O W A Hill N I U L Terrace O E RI N r D CHAR h T e A DSON RD ut S T E iv o R S L Y R N R eek A i Y G r W v C G L e A Motto r N Cliftleigh D Farm rry ige MID-WESTERN REGIONAL D Till R Loxford Heatherbrae -

The Entrance Morphodynamic Modelling Prepared for NSW Office of Environment and Heritage

Tuggerah Lakes– The Entrance Morphodynamic Modelling Prepared for NSW Office of Environment and Heritage Tuggerah Lakes – The Entrance Morphodynamic Modelling Prepared for NSW Office of Environment and Heritage Cardno (NSW/ACT) Pty Ltd ABN 95 001 145 035 Level 9 The Forum 203 Pacific Highway St Leonards NSW 2065 Australia Telephone: 02 9496 7700 Facsimile: 02 9439 5170 International: +61 2 9496 7700 [email protected] www.cardno.com.au © State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage November 2013 This document is produced by Cardno solely for the benefit and use by the client in accordance with the terms of the engagement. Cardno does not and shall not assume any responsibility or liability whatsoever to any third party arising out of any use or reliance by any third party on the content of this document. Tuggerah Lakes – The Entrance Morphodynamic Modelling Prepared for NSW Office of Environment and Heritage EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Tuggerah Lakes system consists of three inter-connected shallow coastal lakes (Tuggerah, Budgewoi and Munmorah) that have a weak and intermittent connection to the ocean at The Entrance. The lakes have a history of water quality issues with development of their catchments leading to increased nutrient, and to a lesser extent sediment, loads. The lakes’ entrance is currently managed through regular dredging by Wyong Council to ensure that the entrance does not close and to achieve objectives related to flooding, water quality in the lower entrance channels and recreational amenity. The dredging does not affect the general water quality in the lakes. Previous assessments have considered the possibility of constructing a training wall or training walls at the entrance to Tuggerah Lakes with the objective of maintaining a permanent entrance to the lakes and thus improving water flows and water quality. -

Settlement of the Tuggerah Lakes

Settlement of the Tuggerah Lakes The ecological history of the Tuggerah Lakes over the last 200 years is closely linked to the pattern of European settlement both around the lakes and within the upper catchment. As settlement spread throughout the district, activities such as the clearing of land, logging, fishing and urban development have all had impacts on the ecology of the lakes. To understand when each of these impacts occurred, the settlement of the Tuggerah Lakes and its catchment has been divided into four broad time periods. These are; • Aboriginal settlement • The first European settlers (1820s – 1870s) • Settlement after the opening of the railway (1880s – 1950s) • Urban Development (1960s – 1990s) Historical documents which provide an insight into the rates of settlement and associated activities during each of these time periods, are presented in the following sections. Table 1 provides a summary of some key dates in the development of the region. Table 1. Significant events in the development of the Tuggerah Lakes and its catchment Date Activity 1825 First settlers arrived. Early 1830s Logging commenced in the upper catchment, principally for cedar. Early 1830s Felton Mathews surveyed the district. 1832 The Great North Road was opened, principally as a means of providing access to the Hunter District from Sydney. There were two branches from this road into Wyong. 1830s Cabbage Tree Harbour provided a shipping point for cedar from the 1830s onwards. Gosford was another such departure point. Early1850s Hargraves residence at Noraville constructed using cedar from the valleys behind Wyong. 1854 Jane Taylor acquired all the land of what is now The Entrance.