India : Before and After the Mutiny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 29 Organization of Scientific Research in Postcolonial India

NPTEL – Humanities and Social Sciences – Science, Technology and Society Lecture 29 Organization of Scientific Research in Postcolonial India The institutionalization and professionalization of scientific research, resulting in the growth of the scientific community in India, has traversed a tumultuous turmoil since the colonial period. The struggle over the colonial science policies and economic exploitation in the areas of industry, mining, forests, etc. and decline in production in artisan-based industry like handloom, and later, after Independence, the efforts to build scientific infrastructure to develop and industrialize India present us with a continuing theme of challenges confronting the scientists in building institutions to pursue science in India. One of the most important scientific research institutions that were set up during the colonial regime was the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784. The Asiatic Society, modeled after the Royal Society of London, was established to carry out historical, anthropological and sociological research on Indian history, culture and ancient texts. The researchers were mostly British administrators, who carried out research, and the Asiatic Society provided a forum for scholars to exchange their ideas and research findings. The amateurs with their Eurocentric perspectives studied the Indian society to guide their administrative practices and legal system that saw the emergence of the Geological Survey of India, the Botanical Survey of India and the Meteorological Survey of India during the colonial period. Scientific research began in universities during the mid-nineteenth century with the establishment of University of Calcutta, University of Bombay and University of Madras in 1857. The nineteenth century also witnessed the establishment of scientific institutions by Muslim intelligentsia. -

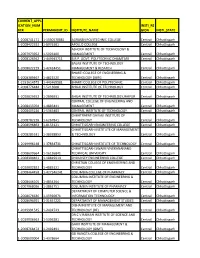

Name of DDO/Hoo ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF

Name of DDO/HoO ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF. NO. BARCODE DATE THE SUPDT OF POLICE (ADMIN),SPL INTELLIGENCE COUNTER INSURGENCY FORCE ,W B,307,GARIA GROUP MAIN ROAD KOLKATA 700084 FUND IX/OUT/33 ew484941046in 12-11-2020 1 BENGAL GIRL'S BN- NCC 149 BLCK G NEW ALIPUR KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700053 FD XIV/D-325 ew460012316in 04-12-2020 2N BENAL. GIRLS BN. NCC 149, BLOCKG NEW ALIPORE KOL-53 0 NEW ALIPUR 700053 FD XIV/D-267 ew003044527in 27-11-2020 4 BENGAL TECH AIR SAQ NCC JADAVPUR LIMIVERSITY CAMPUS KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700032 FD XIV/D-313 ew460011823in 04-12-2020 4 BENGAL TECH.,AIR SQN.NCC JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, KOLKATA 700036 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/468 EW460018693IN 26-11-2020 6 BENGAL BATTALION NCC DUTTAPARA ROAD 0 0 N.24 PGS 743235 FD XIV/D-249 ew020929090in 27-11-2020 A.C.J.M. KALYANI NADIA 0 NADIA 741235 FD XII/D-204 EW020931725IN 17-12-2020 A.O & D.D.O, DIR.OF MINES & MINERAL 4, CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-XIV/JAL/19-20/OUT/30 ew484927906in 14-10-2020 A.O & D.D.O, O/O THE DIST.CONTROLLER (F&S) KARNAJORA, RAIGANJ U/DINAJPUR 733130 FUDN-VII/19-20/OUT/649 EW020926425IN 23-12-2020 A.O & DDU. DIR.OF MINES & MINERALS, 4 CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-IV/2019-20/OUT/107 EW484937157IN 02-11-2020 STATISTICS, JT.ADMN.BULDS.,BLOCK-HC-7,SECTOR- A.O & E.O DY.SECY.,DEPTT.OF PLANNING & III, KOLKATA 700106 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/470 EW460018716IN 26-11-2020 A.O & EX-OFFICIO DY.SECY., P.W DEPTT. -

JNAN CHANDRA GHOSH JNAN CHANDRA GHOSH Will Be

JNAN CHANDRA GHOSH JNAN CHANDRAGHOSH will be remembered for his fundamental contribu- tions to the theory of strong electrolytes which created a great impression . on such leaders of science like Walter Nernst, Max Planck, Sir William Bragg, Prof. G. N. Lewis apd others. He will also be remembered for his contributions to the promotion of education, science and technology; the foundation and development of (a) the Department of Chemistry in the then newly founded Dacca University and (b) the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur and his services to the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. As Vice-Chancellor of the Calcutta University he made unique contributions to student welfare by providing facilities for study, rest and recreation to a large floating population of students of the colleges affiliated to the University of Calcutta. As a member of the Governing Body and the Board of the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research and of several of its Committees he materially contributed to the development of the Council and the National Laboratories under it. As the first scientist appointed as Director-General of Disposals and Supplies he helped the Government of India in plans of development of resources. Later as a member of the Planning Commission he helped the development of education, and of science and its applications under the Five Year Plans. He has also made notable contributions to the develop- ment of science as PresidentJMember of a large number of learned scientific societies including the National Institute of Sciences of India. Jnan Chandra was born at Purulia on September 4, 1893. His father Ram Chandra Ghosh owned a mica mine and was in an affluent condition when Jnan Chandra was born. -

Year Book of the Indian National Science Academy

AL SCIEN ON C TI E Y A A N C A N D A E I M D Y N E I A R Year Book B of O The Indian National O Science Academy K 2019 2019 Volume I Angkor, Mob: 9910161199 Angkor, Fellows 2019 i The Year Book 2019 Volume–I S NAL CIEN IO CE T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N I INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY New Delhi ii The Year Book 2019 © INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY ISSN 0073-6619 E-mail : esoffi [email protected], [email protected] Fax : +91-11-23231095, 23235648 EPABX : +91-11-23221931-23221950 (20 lines) Website : www.insaindia.res.in; www.insa.nic.in (for INSA Journals online) INSA Fellows App: Downloadable from Google Play store Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) Professor Gadadhar Misra, FNA Production Dr VK Arora Shruti Sethi Published by Professor Gadadhar Misra, Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) on behalf of Indian National Science Academy, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002 and printed at Angkor Publishers (P) Ltd., B-66, Sector 6, NOIDA-201301; Tel: 0120-4112238 (O); 9910161199, 9871456571 (M) Fellows 2019 iii CONTENTS Volume–I Page INTRODUCTION ....... v OBJECTIVES ....... vi CALENDAR ....... vii COUNCIL ....... ix PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xi RECENT PAST VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xii SECRETARIAT ....... xiv THE FELLOWSHIP Fellows – 2019 ....... 1 Foreign Fellows – 2019 ....... 154 Pravasi Fellows – 2019 ....... 172 Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 173 Foreign Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 177 Fellowship – Sectional Committeewise ....... 178 Local Chapters and Conveners ...... -

Congress in the Politics of West Bengal: from Dominance to Marginality (1947-1977)

CONGRESS IN THE POLITICS OF WEST BENGAL: FROM DOMINANCE TO MARGINALITY (1947-1977) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL For the award of Doctor of Philosophy In History By Babulal Bala Assistant Professor Department of History Raiganj University Raiganj, Uttar Dinajpur, 733134 West Bengal Under the Supervision of Dr. Ichhimuddin Sarkar Former Professor Department of History University of North Bengal November, 2017 1 2 3 4 CONTENTS Page No. Abstract i-vi Preface vii Acknowledgement viii-x Abbreviations xi-xiii Introduction 1-6 Chapter- I The Partition Colossus and the Politics of Bengal 7-53 Chapter-II Tasks and Goals of the Indian National Congress in West Bengal after Independence (1947-1948) 54- 87 Chapter- III State Entrepreneurship and the Congress Party in the Era of Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy – Ideology verses Necessity and Reconstruction 88-153 Chapter-IV Dominance with a Difference: Strains and Challenges (1962-1967) 154-230 Chapter- V Period of Marginalization (1967-1971): 231-339 a. Non-Congress Coalition Government b. Presidential Rule Chapter- VI Progressive Democratic Alliance (PDA) Government – Promises and Performances (1972-1977) 340-393 Conclusion 394-395 Bibliography 396-406 Appendices 407-426 Index 427-432 5 CONGRESS IN THE POLITICS OF WEST BENGAL: FROM DOMINANCE TO MARGINALITY (1947-1977) ABSTRACT Fact remains that the Indian national movement found its full-flagged expression in the activities and programmes of the Indian National Congress. But Factionalism, rival groupism sought to acquire control over the Congress time to time and naturally there were confusion centering a vital question regarding ‘to be or not to be’. -

List of Approved Institutes in 2014-15

CURRENT_APPL ICATION_NUM INSTI_RE BER PERMANENT_ID INSTITUTE_NAME GION INSTI_STATE 1-2008741171 1-1590578881 AGRASEN POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE Central Chhattisgarh 1-2008422333 1-8976101 APOLLO COLLEGE Central Chhattisgarh ASHOKA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & 1-2007973952 1-5926100 MANAGEMENT Central Chhattisgarh 1-2008126942 1-449943711 B.R.P. GOVT. POLYTECHNIC DHAMTARI Central Chhattisgarh BALAJI INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 1-2008622229 1-42424451 MANAGEMENT & RESARCH Central Chhattisgarh BHARTI COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & 1-2008389467 1-4821520 TECHNOLOGY DURG Central Chhattisgarh 1-2191614575 1-440465581 BHARTI COLLEGE OF POLYTECHNIC Central Chhattisgarh 1-2008776484 1-5213608 BHILAI INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Central Chhattisgarh 1-2020029552 1-2896931 BHILAI INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY,RAIPUR. Central Chhattisgarh CENTRAL COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND 1-2008433704 1-4885441 MANAGEMENT Central Chhattisgarh 1-2008405226 1-5365483 CENTRAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Central Chhattisgarh CHHATRAPATI SHIVAJI INSTITUTE OF 1-2008782228 1-6267841 TECHNOLOGY Central Chhattisgarh 1-2008596863 1-8153121 CHHATTISGARH ENGINEERING COLLEGE Central Chhattisgarh CHHATTISGARH INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT 1-2008285531 1-38338853 & TECHNOLOGY Central Chhattisgarh 1-2019996148 1-37834731 CHHATTISGARH INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Central Chhattisgarh CHHATTISGARH SWAMI VIVEKANANAND 1-2008600664 1-16126841 TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY Central Chhattisgarh 1-2008394461 1-18819914 CHOUKSEY ENGINEERING COLLEGE Central Chhattisgarh CHRISTIAN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND 1-2020002833 1-4885121 TECHNOLOGY Central -

Shyama Prasad Mukherjee As Minister for Civil Supplies and Industry in Nehru’S National Cabinet

Centenary of Science Departments in Indian Universities : A comprehension$ A K Grover* Chemical Society Seminar$ February 11, 2019, IIT Delhi, New Delhi *Honorary Emeritus Professor, Punjab Engineering College (Deemed to be University), Chandigarh, Chairperson, Research Council, NPL, New Delhi (2017-19), Ex-Vice Chancellor (2012-18), P. U., Chandigarh & Senior Prof. (Retd.), TIFR,Mumbai [email protected] $This talk is dedicated to Ruchi Ram Sahni, S S Bhatnagar and Homi J Bhabha An extract from the Abstract Establishment of Hindu College by Raja Ram Mohan Rai in Calcutta in 1817 marks the beginning of secular English education in India. The College was taken over by the then government in 1854 and renamed Presidency College. Calcutta University was set up in 1857 as a merely examining body. Sixty years later (in 1917), its legendary Vice Chancellor (VC) Justice Sir Asutosh Mukherjee (1864-1924) could succeed in nucleating the University Departments for post graduate teaching and research, concurrent with the assumption of Palit Professorship by Sir C V Raman at Indian Association of Cultivation of Science (IACS), and induction of University toppers, like, Megh Nad Saha, Satyendra Nath Bose, Sisir Kumar Mitra, Sudhangshu Kumar Banerjee, Jnan Chandra Ghosh and Jnanendra Nath Mukherjee in the newly created University College of Science as research and teaching faculty. This success spurred its replication in other Universities of India. Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee CSI, FASB, FRSE, FRAS, MRIA (29.6.1864-25.5.1924) • A prolific Bengali educator, jurist, barrister and a Mathematician. • First student to be awarded a dual degree (MA in Mathematics and Physics) from Calcutta University. -

Meghnad Saha: a Brief History 1 Ajoy Ghatak

A Publication of The National Academy of Sciences India (NASI) Publisher’s note Every possible eff ort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this book is accurate at the time of going to press, and the publisher and authors cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions, however caused. No responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting, or refraining from action, as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by the editors, the publisher or the authors. Every eff ort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material used in this book. Th e authors and the publisher will be grateful for any omission brought to their notice for acknowledgement in the future editions of the book. Copyright © Ajoy Ghatak and Anirban Pathak All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise, without the written permission of the editors. First Published 2019 Viva Books Private Limited • 4737/23, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002 Tel. 011-42242200, 23258325, 23283121, Email: [email protected] • 76, Service Industries, Shirvane, Sector 1, Nerul, Navi Mumbai 400 706 Tel. 022-27721273, 27721274, Email: [email protected] • Megh Tower, Old No. 307, New No. 165, Poonamallee High Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095 Tel. 044-23780991, 23780992, 23780994, Email: [email protected] • B-103, Jindal Towers, 21/1A/3 Darga Road, Kolkata 700 017 Tel. 033-22816713, Email: [email protected] • 194, First Floor, Subbarama Chetty Road Near Nettkallappa Circle, Basavanagudi, Bengaluru 560 004 Tel. -

Darwin in Stellar Astrophysics Meghnad Saha

Book Review a figure of international renown. While his pioneering work on Thermal Ionisation and its global impact have been dealt with in ample details - there are at least two distinctive features of this tome. First, an attempt has been made, with hindsight, to understand how his work had triggered the development of a new branch of physics to mark him as the ‘Darwin of Stellar Astrophysics’. Second, this work includes personal reminiscences of Saha’s living daughters and family members that illuminate his personality - as a loving guide to endless stream of students and an affectionate father to his seven children. To give an idea of the contents, here is a chapter- wise breakup. Prof. Ajoy Ghatak, one of the editors and a distinguished physicist himself, provides a biographical sketch and explains, in simple terms, Saha’s ionization formula. Thereafter, the renowned astrophysicist Jayant V. Narlikar discusses The Saha Equation and Beyond. Saha’s youngest son, Prasenjit, explores his father’s work through letters and correspondence (1917-1936). The fourth chapter reproduces the comments by two leading astrophysicists, DARWIN OF STELLAR ASTROPHYSICS Henry Norris Russell and Arthur Eddington, about the MEGHNAD SAHA by Shyamal Bhadra, Rik decisive impact of Saha’s path-breaking work. Chattopadhyay and Ajoy Ghatak; published The fifth chapter projects Meghnad Saha as Father, by Viva Books, New Delhi (2019), Pages xxvi as recollected by his three living daughters and the eldest + 302, Price ` 995 daughter-in-law - Krishna Das, Chitra Roy, Sanghamitra Roy and Biswabani Saha. Chapter six comprises five n a life of sixty-three years, Meghnad Saha (1893-1956) tributes by noted scientists like (Sir) Jnan Chandra Ghosh, Icombined in himself so many roles and achieved so much Debendramohan Bose, Santimay Chatterjee, Sam Kean and of distinction in each of them that he continues to be A.A. -

Science, Technology and the Shifting Imperatives of National Politics

Science, Technology and the shifting imperatives of national politics-Gandhi , Bose and Nehru • were significant debates on the question of linkages between science and technology, on one hand, and, Indian society, on the other, among the national political leadership even before India attained independence • The discussion on the economic, historical and cultural dimensions of science and technology that figured in Science and Culture, on one hand, and, of various collected works of political leaders of the Indian National Congress (INC), viz., Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose • The question of modern science and technology elicited a variety of responses, that ranged from questioning the potential of modern science and technology in the process of nation-building, to acknowledging the transformative potential of modern science and technology Mohandas Karamchand Ganidhi’s Perceptions of Science • During and after the World War I, the programme of the Indian National Congress (INC) of reviving and restoring traditional industries and crafts was not only going on but also parallel developments favourable to the advancement of modern science and technology were also set in motion • On a global scale, the aftermath of the World War I and the achievements of Socialist experiments in the erstwhile USSR unveiled the immense potentialities of science for mankind in terms of the economy and material progress • Moreover, the global economic crisis in the form of the Great Depression 1933 and the subsequent crisis of the bi-polar world compelled the leadership to have a fresh look at each aspect of society - be it social, economic political. • In the process, the earlier INC policy, as a whole, and the 'Gandhian philosophy', to a great extent, gave way to new • The term, 'Gandhian philosophy' needs to be explained here. -

Becoming a Bengali Woman: Exploring Identities in Bengali Women’S Fiction, 1930-1955

1 Becoming a Bengali Woman: Exploring Identities in Bengali Women’s Fiction, 1930-1955 Sutanuka Ghosh Ph.D Thesis School of Oriental and African Studies University of London July 2007 aiat ProQuest Number: 11010507 All rights reserved IN F O R M A T IO N T O A LL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 I hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own. Sutanuka Ghosh 3 Abstract History seldom tells the story of ordinary men far less ordinary women. This thesis explores the tales of ordinary middle class Hindu Bengali women and their different experiences of the period 1930-1955 through fiction written by women. To undermine the logic of colonialism the Indian nationalist movement had sought to project an image of a modern, progressive, egalitarian society while also holding on to its distinctive cultural identity. The fulfilment of these twin objectives hinged on Indian women. Consequently Bengali women found themselves negotiating different objectives that required them to be ‘modern’ as well as patient, self-sacrificing, pure and faithful like Sita. -

Report J 969-70

REPORT J 969-70 'GOVERNMENT OF INDIA M # EDUCATION * f OUTH f SERVICES n e w m i m CONTENTS P a g e C h a p t e r I General Review . ....T II School Education ....... 22 III Higher Education . .... 31 IV Technical Education ...... 41 V Scientific Surveys and Development .... 5i VI Council of Scientific and Industrial Research 61 VII Scholarships ........ 69 V III Development of Languages ..... 81 IX Book P r o m o t i o n ................................................................... 94 X Physical Education, Gam^s, Sports, Youth Services and Youth Welfare ....... 107 X I S vji.il Science Research, Pilot Projects and Clearing House Functions . .... 115 X II Cultural Affairs ....... 1 2 5 Xi.II U:ieso anl Cultural Relations with Other Countries 145 XIV Adult Education, Libraries and Gazetteers 159’ XV Education in Union Territories ..... 16 9 XVI Other Programmes ....... 1 8a A n n e x u r e s I Attached and Subordinate Offices .... 189 II Publications Brought Out ...... 198 III Statement showing the Country-wise Number of Indian Scholarship-holders Studying Abroad .... 2 2 0 IV Statement showing the Country-wise Number of Foreign Scholars Studying in India . 22K (“) C harts P a g e I Administrative Chart of the Ministry of Education and Youth Services ...... 2 2 3 II Progress of Primary Education .... 2 25 III Progress of Middle Education . 226 IV Progress of Secondary Education » . 227 V Progress of University Education . 228 'VI Progress of Technical Education . 729 'VII Progress of Expenditure on Education by Sources 210 CHAPTER I GENERAL REVIEW 1.01.