A DEVASTATING DECADE Violations of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law in the Syrian War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

Spotlight on Iran (October 15-29, 2017)

Spotlight on Iran October 15-29, 2017 Author: Dr. Raz Zimmt Overview At the center of events of the past two weeks was the visit to Syria of the Chief of Staff of the Iranian Armed Forces, Mohammad Bagheri. This is Bagheri’s second official visit outside of Iran since assuming his post in June 2016, following his visit to Turkey in August.. During his visit, Bagheri met with President Assad, the Syrian minister of defense and the Syrian chief of staff and discussed with them developments in the Syrian battlefield and increasing military and security cooperation between the two countries. Bagheri conveyed a personal message from the Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei and toured the frontlines in the areas of Aleppo and Lattakia. The visit of the Iranian chief of staff represents another step in the Iranian effort to gain a long-term military foothold in Syria and increase its influence in Syria in the post-ISIS era. Meanwhile, the fighting in Syria continues to exact its toll on Iranian forces: a commander of an Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) battalion and three additional fighters were killed in Syria in the past two weeks. Alongside its military effort, Iran is acting to increase its religious influence in Syria. Last week, a senior Iranian official declared that the dispatch of Iranian pilgrims to the Shi’ite holy sites in Syria will be soon renewed. The director of the Headquarter for Reconstruction of Shia Holy Sites in Syria and Iraq stated that over the past year, Iran has carried out reconstruction and restoration work of the holy Shi’ite sites in Syria, which were damaged in the fighting during the civil war, most important among them being the Sayyidah Zaynab Shrine south of Damascus. -

International Activity Report 2017

INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITY REPORT 2017 www.msf.org THE MÉDECINS SANS FRONTIÈRES CHARTER Médecins Sans Frontières is a private international association. The association is made up mainly of doctors and health sector workers, and is also open to all other professions which might help in achieving its aims. All of its members agree to honour the following principles: Médecins Sans Frontières provides assistance to populations in distress, to victims of natural or man-made disasters and to victims of armed conflict. They do so irrespective of race, religion, creed or political convictions. Médecins Sans Frontières observes neutrality and impartiality in the name of universal medical ethics and the right to humanitarian assistance, and claims full and unhindered freedom in the exercise of its functions. Members undertake to respect their professional code of ethics and to maintain complete independence from all political, economic or religious powers. As volunteers, members understand the risks and dangers of the missions they carry out and make no claim for themselves or their assigns for any form of compensation other than that which the association might be able to afford them. The country texts in this report provide descriptive overviews of MSF’s operational activities throughout the world between January and December 2017. Staffing figures represent the total full-time equivalent employees per country across the 12 months, for the purposes of comparisons. Country summaries are representational and, owing to space considerations, may not be comprehensive. For more information on our activities in other languages, please visit one of the websites listed on p. 100. The place names and boundaries used in this report do not reflect any position by MSF on their legal status. -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – March 2018 Page 1

Aid in Danger Aid agencies Monthly News Brief March 2018 Insecurity affecting the delivery of aid Security Incidents and Access Constraints This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of Africa violence affecting the delivery Central African Republic of aid. It is prepared by 05 March 2018: In Paoua town, Ouham-Pendé prefecture, and across Insecurity Insight from the wider Central African Republic, fighting among armed groups information available in open continues to stall humanitarian response efforts. Source: Devex sources. 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, rumours of All decisions made, on the basis an armed attack in the city forced several unspecified NGOs to of, or with consideration to, withdraw. Source: RJDH such information remains the responsibility of their 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, protesters at respective organisations. a women’s march against violence in the region called for the departure of MINUSCA and the Moroccan UN contingent from Editorial team: Bangassou, accusing them of passivity in the face of threats and Christina Wille, Larissa Fast and harassment. Source: RJDH Laurence Gerhardt Insecurity Insight 09 or 11 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, armed men suspected to be from the Anti-balaka movement invaded the Andrew Eckert base of the Dutch NGO Cordaid, looting pharmaceuticals, work tools, European Interagency Security motorcycles and seats. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Forum (EISF) Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) personnel intervened, leading to a firefight between MINUSCA and the armed Research team: men. The perpetrators subsequently vandalised the local Médecins James Naudi Sans Frontières (MSF) office. Cars, motorbikes and solar panels Insecurity Insight belonging to several NGOs in the area were also stolen. -

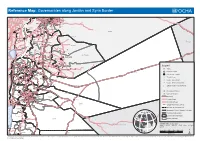

Reference Map: Governorates Along Jordan and Syria Border

Reference Map:] Governorates along Jordan and Syria Border Qudsiya Yafur Tadmor Sabbura Damascus DAMASCUS Obada Nashabiyeh Damascus Maliha Qisa Otayba Yarmuk Zabadin Deir Salman Madamiyet ElshamDarayya Yalda Shabaa Haran Al'awameed Qatana Jdidet Artuz Sbeineh Hteitet Elturkman LEBONAN Artuz Sahnaya Buwayda ] Hosh Sahya Jdidet Elkhas A Tantf DarwashehDarayya Ghizlaniyyeh Khan Elshih Adleiyeh Deir Khabiyeh MqeilibehKisweh Hayajneh Qatana ZahyehTiba Khan Dandun Mazraet Beit Jin Rural Damascus Sa'sa' Hadar Deir Ali Kanaker Duma Khan Arnaba Ghabagheb Jaba Deir Elbakht SYRIA Quneitra Kafr Shams Aqraba Jbab Nabe Elsakher Quneitra As-Sanamayn Hara As-Sanamayn IRAQ Nimer Ankhal Qanniyeh I Jasim Shahba Mahjeh S Nawa Shaqa R Izra' Izra' Shahba Tassil Sheikh Miskine Bisr Elharir A Al Fiq Qarfa Nemreh Abtaa Nahta E Ash-Shajara As-Sweida Da'el Alma Hrak Western Maliha Kherbet Ghazala As-Sweida L Thaala As-Sweida Saham Masad Karak Yadudeh Western Ghariyeh Raha Eastern Ghariyeh Um Walad Bani kinana Kharja Malka Torrah Al'al Mseifra Kafr Shooneh Shamaliyyeh Dar'a Ora Bait Ras Mghayyer Dar'a Hakama ManshiyyehWastiyya Soom Sal Zahar Daraa] Dar'a Tiba Jizeh Irbid Boshra Waqqas Ramtha Nasib Moraba Legend Taibeh Howwarah Qarayya Sammo' Shaikh Hussein Aidoon ! Busra Esh-Sham Arman Dair Abi Sa'id Irbid ] Milh AlRuwaished Salkhad Towns Kofor El-Ma' Nassib Bwaidhah Salkhad Mazar Ash-shamaliCyber City Mghayyer Serhan Mashari'eKora AshrafiyyehBani Obaid ! National Capital Kofor Owan Badiah Ash-Shamaliyya Al_Gharbeh Rwashed Kofor Abiel NULL Ketem ! Jdaitta No'ayymeh -

"Al-Assad" and "Al Qaeda" (Day of CBS Interview)

This Document is Approved for Public Release A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad A Quick Look Assessment by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA)1 Part II: Analytical Approaches2 February 2014 Contributors: Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (University of British Columbia), Mr. Ryan W. Cross (University of British Columbia) Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Maj Jason Spitaletta (Joint Staff J-7 & Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Kathleen Egan (CTTSO), Mr. Sean Colbath (BBN), Mr. Paul Brewer (SDL), Ms. Martha Lillie (BBN), Mr. Dana Rafter (CSIS), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M), Ms. Jacquelyn Chinn (Texas A&M), Mr. Patrick Issa (Texas A&M) Edited by: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J-38) and Dr. Nicholas Wright, MRCP PhD (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Copy Editor: Mr. Sam Rhem (SRC) 1 SMA provides planning support to Combatant Commands (CCMD) with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff, J3, DDSAO and executed by OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO. 2 This is a document submitted to provide timely support to ongoing concerns as of February 2014. 1 This Document is Approved for Public Release 1 ABSTRACT This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources. -

Losing Their Last Refuge: Inside Idlib's Humanitarian Nightmare

Losing Their Last Refuge INSIDE IDLIB’S HUMANITARIAN NIGHTMARE Sahar Atrache FIELD REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2019 Cover Photo: Displaced Syrians are pictured at a camp in Kafr Lusin near the border with Turkey in Idlib province in northwestern Syria. Photo Credit: AAREF WATAD/AFP/Getty Images. Contents 4 Summary and Recommendations 8 Background 9 THE LAST RESORT “Back to the Stone Age:” Living Conditions for Idlib’s IDPs Heightened Vulnerabilities Communal Tensions 17 THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE UNDER DURESS Operational Challenges Idlib’s Complex Context Ankara’s Mixed Role 26 Conclusion SUMMARY As President Bashar al-Assad and his allies retook a large swath of Syrian territory over the last few years, rebel-held Idlib province and its surroundings in northwest Syria became the refuge of last resort for nearly 3 million people. Now the Syrian regime, backed by Russia, has launched a brutal offensive to recapture this last opposition stronghold in what could prove to be one of the bloodiest chapters of the Syrian war. This attack had been forestalled in September 2018 by a deal reached in Sochi, Russia between Russia and Turkey. It stipulated the withdrawal of opposition armed groups, including Hay’at Tahrir as-Sham (HTS)—a former al-Qaeda affiliate—from a 12-mile demilitarized zone along the front lines, and the opening of two major HTS-controlled routes—the M4 and M5 highways that cross Idlib—to traffic and trade. In the event, HTS refused to withdraw and instead reasserted its dominance over much of the northwest. By late April 2019, the Sochi deal had collapsed in the face of the Syrian regime’s military escalation, supported by Russia. -

Assessing the French Perspectve on American

ASSESSING THE FRENCH PERSPECTVE ON AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR THROUGH THE 2016 BOMBINGS IN ALEPPO AND FRENCH NEWS MEDIA by KATHERINE GOLAB A THESIS Presented to the Department of Romance Languages and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2020 An Abstract of the Thesis of Katherine Golab for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Romance Languages to be taken June 2020 Title: Assessing the French Perspective on American Involvement in the Syrian Civil War Through the 2016 Bombings in Aleppo and French News Media Approved: Géraldine Poizat-Newcomb, Ph.D. Primary Thesis Advisor As two members of the United Nations’ “Big Five” countries, it is clear that France and the United States of America are both influential global powers. Since America’s independence, the two countries have shared a long and enduring political relationship, which has greatly shaped how each respective culture has influenced the other. Due to their shared history and interdependent power dynamics, current events play an important role in the maintenance of their relationship, which is also heavily present in their shared interests in the Syrian Civil War. This work includes the translation and analysis of 12 articles from four influential French news media organizations to document and explore the French perception of the United States through their news media outlets, in relation to the 2016 attacks on Aleppo. Since both countries have been actively involved in the conflict since its inception, this compilation and analysis sheds light on French-American cooperation, their political connections, and their social relationships. -

A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of Idps As a Result 0.Pdf

A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result About Syrians for Truth and Justice-STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) is an independent, nongovernmental organization whose members include Syrian human rights defenders, advocates and academics of different backgrounds and nationalities. The initiative strives for SYRIA, where all Syrian citizens (males and females) have dignity, equality, justice and equal human rights . 1 A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result A flash report highlighting the bombardment on the western and eastern countryside of Daraa from 15 to 20 June 2018 2 A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result Preface With blatant disregard of all the warnings of the international community and UN, pro- government forces launched a major military escalation against Daraa Governorate, as from 15 to 20 June 2018. According to STJ researchers, many eyewitnesses and activists from Daraa, Syrian forces began to mount a major offensive against the armed opposition factions held areas by bringing reinforcements from various regions of the country a short time ago. The scale of these reinforcements became wider since June 18, 2018, as the Syrian regime started to send massive military convoys and reinforcements towards Daraa . Al-Harra and Agrabaa towns, as well as Kafr Shams city located in the western countryside of Daraa1, have been subjected to artillery and rocket shelling which resulted in a number of civilian causalities dead or wounded. Daraa’s eastern countryside2 was also shelled, as The Lajat Nahitah and Buser al Harir towns witnessed an aerial bombardment by military aircraft of the Syrian regular forces on June 19, 2018, causing a number of civilian casualties . -

Commentary on the EASO Country of Origin Information Reports on Syria (December 2019 – May 2020) July 2020

Commentary on the EASO Country of Origin Information Reports on Syria (December 2019 – May 2020) July 2020 1 © ARC Foundation/Dutch Council for Refugees, June 2020 ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees publications are covered by the Create Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC Foundation publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees and it is for non- commercial use. ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees do not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. ARC Foundation is extremely grateful to Paul Hamlyn Foundation for its support of ARC’s involvement in this project. Feedback and comments Please help us to improve and to measure the impact of our publications. We’d be most grateful for any comments and feedback as to how the reports have been used in refugee status determination processes, or beyond: https://asylumresearchcentre.org/feedback/. Thank you. Please direct any questions to [email protected]. 2 Contents Introductory remarks ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Key observations ................................................................................................................................................ 5 General methodological observations and recommendations ......................................................................... 9 Comments on any forthcoming