CONSTRAINT INTERACTION and WRITING SYSTEMS TYPOLOGY Antonio Baroni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Similarities and Dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: a Comparative Study

Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic 94 Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: A Comparative Study MD YEAQUB Research Scholar Aligarh Muslim University, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper will focus on a comparative study about similarities and dissimilarities of the pronunciation between the syllables of English and Arabic with the help of phonetic and phonological tools i.e. manner of articulation, point of articulation and their distribution at different positions in English and Arabic Alphabets. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the alphabets of English and Arabic can be useful in overcoming the hindrances for those want to improve the pronunciation of both English and Arabic languages. We all know that Arabic is a Semitic language from the Afro-Asiatic Language Family. On the other hand, English is a West Germanic language from the Indo- European Language Family. Both languages show many linguistic differences at all levels of linguistic analysis, i.e. phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, etc. For this we will take into consideration, the segmental features only, i.e. the consonant and vowel system of the two languages. So, this is better and larger to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learners’ outcomes. Keywords: Arabic Alphabets, English Alphabets, Pronunciations, Phonetics, Phonology, manner of articulation, point of articulation. Introduction: We all know that sounds are generally divided into two i.e. consonants and vowels. A consonant is a speech sound, which obstruct the flow of air through the vocal tract. -

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

A Practical Sanskrit Introductory

A Practical Sanskrit Intro ductory This print le is available from ftpftpnacaczawiknersktintropsjan Preface This course of fteen lessons is intended to lift the Englishsp eaking studentwho knows nothing of Sanskrit to the level where he can intelligently apply Monier DhatuPat ha Williams dictionary and the to the study of the scriptures The rst ve lessons cover the pronunciation of the basic Sanskrit alphab et Devanagar together with its written form in b oth and transliterated Roman ash cards are included as an aid The notes on pronunciation are largely descriptive based on mouth p osition and eort with similar English Received Pronunciation sounds oered where p ossible The next four lessons describ e vowel emb ellishments to the consonants the principles of conjunct consonants Devanagar and additions to and variations in the alphab et Lessons ten and sandhi eleven present in grid form and explain their principles in sound The next three lessons p enetrate MonierWilliams dictionary through its four levels of alphab etical order and suggest strategies for nding dicult words The artha DhatuPat ha last lesson shows the extraction of the from the and the application of this and the dictionary to the study of the scriptures In addition to the primary course the rst eleven lessons include a B section whichintro duces the student to the principles of sentence structure in this fully inected language Six declension paradigms and class conjugation in the present tense are used with a minimal vo cabulary of nineteen words In the B part of -

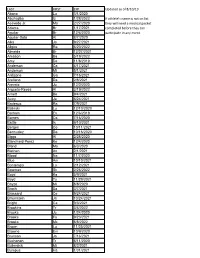

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Kharosthi Manuscripts: a Window on Gandharan Buddhism*

KHAROSTHI MANUSCRIPTS: A WINDOW ON GANDHARAN BUDDHISM* Andrew GLASS INTRODUCTION In the present article I offer a sketch of Gandharan Buddhism in the centuries around the turn of the common era by looking at various kinds of evidence which speak to us across the centuries. In doing so I hope to shed a little light on an important stage in the transmission of Buddhism as it spread from India, through Gandhara and Central Asia to China, Korea, and ultimately Japan. In particular, I will focus on the several collections of Kharo~thi manuscripts most of which are quite new to scholarship, the vast majority of these having been discovered only in the past ten years. I will also take a detailed look at the contents of one of these manuscripts in order to illustrate connections with other text collections in Pali and Chinese. Gandharan Buddhism is itself a large topic, which cannot be adequately described within the scope of the present article. I will therefore confine my observations to the period in which the Kharo~thi script was used as a literary medium, that is, from the time of Asoka in the middle of the third century B.C. until about the third century A.D., which I refer to as the Kharo~thi Period. In addition to looking at the new manuscript materials, other forms of evidence such as inscriptions, art and architecture will be touched upon, as they provide many complementary insights into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara. The travel accounts of the Chinese pilgrims * This article is based on a paper presented at Nagoya University on April 22nd 2004. -

2020 Language Need and Interpreter Use Study, As Required Under Chair, Executive and Planning Committee Government Code Section 68563 HON

JUDICIAL COUNCIL OF CALIFORNIA 455 Golden Gate Avenue May 15, 2020 San Francisco, CA 94102-3688 Tel 415-865-4200 TDD 415-865-4272 Fax 415-865-4205 www.courts.ca.gov Hon. Gavin Newsom Governor of California HON. TANI G. CANTIL- SAKAUYE State Capitol, First Floor Chief Justice of California Chair of the Judicial Council Sacramento, California 95814 HON. MARSHA G. SLOUGH Re: 2020 Language Need and Interpreter Use Study, as required under Chair, Executive and Planning Committee Government Code section 68563 HON. DAVID M. RUBIN Chair, Judicial Branch Budget Committee Chair, Litigation Management Committee Dear Governor Newsom: HON. MARLA O. ANDERSON Attached is the Judicial Council report required under Government Code Chair, Legislation Committee section 68563, which requires the Judicial Council to conduct a study HON. HARRY E. HULL, JR. every five years on language need and interpreter use in the California Chair, Rules Committee trial courts. HON. KYLE S. BRODIE Chair, Technology Committee The study was conducted by the Judicial Council’s Language Access Hon. Richard Bloom Services and covers the period from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2017–18. Hon. C. Todd Bottke Hon. Stacy Boulware Eurie Hon. Ming W. Chin If you have any questions related to this report, please contact Mr. Douglas Hon. Jonathan B. Conklin Hon. Samuel K. Feng Denton, Principal Manager, Language Access Services, at 415-865-7870 or Hon. Brad R. Hill Ms. Rachel W. Hill [email protected]. Hon. Harold W. Hopp Hon. Hannah-Beth Jackson Mr. Patrick M. Kelly Sincerely, Hon. Dalila C. Lyons Ms. Gretchen Nelson Mr. -

Finnish Inserted Vowels: a Case of Phonologized Excrescence

Nordic Journal of Linguistics (2021), page 1 of 31 doi:10.1017/S033258652100007X ARTICLE Finnish inserted vowels: a case of phonologized excrescence Robin Karlin University of Wisconsin-Madison, Waisman Center, Madison, WI, 53705, USA Email for correspondence: [email protected] (Received 12 March 2019; revised 1 September 2020; accepted 10 December 2020) Abstract In this paper, I examine a case of vowel insertion found in Savo and Pohjanmaa dialects of Finnish that is typically called “epenthesis”, but which demonstrates characteristics of both phonetic excrescence and phonological epenthesis. Based on a phonological analysis paired with an acoustic corpus study, I argue that Finnish vowel insertion is the mixed result of phonetic excrescence and the phonologization of these vowels, and is related to second-mora lengthening, another dialectal phenomenon. I propose a gestural model of second-mora lengthening that would generate vowel insertion in its original phonetic state. The link to second-mora lengthening provides a unified account that addresses both the dialectal and phonological distribution of the phenomenon, which have not been linked in previous literature. Keywords: excrescence; epenthesis; Finnish; gestures; phonetics; phonology 1. Introduction In this paper, I examine a case of vowel insertion found in Savo and Pohjanmaa dialects of Finnish that has typically been analyzed as a phonological repair, but which demonstrates characteristics of both phonetic excrescence and phonological epenthesis. Using both acoustic data and a phonological analysis of the distribution, I argue that Finnish vowel insertion originated as a phonetic intrusion, but then became phonologized over time. I follow Hall (2006) in assuming that excrescent vowels are the result of gestural underlap, and argue that the original gestural underlap was caused by second-mora lengthening, another phenomenon present in these dialects. -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN ANALYSIS OF CURRENT TRENDS FOR SANSKRIT AS A COMPUTER PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE Manish Tiwari1 and S. Snehlata2 1Department of Computer Science and Application, St. Aloysius College, Jabalpur. 2Student, Deparment of Computer Science and Application, St. Aloysius College, Jabalpur. ABSTRACT : Sanskrit is said to be one of the systematic language with few exception and clear rules discretion.The discussion is continued from last thirtythat language could be one of best option for computers.Sanskrit is logical and clear about its grammatical and phonetically laws, which are not amended from thousands of years. Entire Sanskrit grammar is based on only fourteen sutras called Maheshwar (Siva) sutra, Trimuni (Panini, Katyayan and Patanjali) are responsible for creation,explainable and exploration of these grammar laws.Computer as machine,requires such language to perform better and faster with less programming.Sanskrit can play important role make computer programming language flexible, logical and compact. This paper is focused on analysis of current status of research done on Sanskrit as a programming languagefor .These will the help us to knowopportunity, scope and challenges. KEYWORDS : Artificial intelligence, Natural language processing, Sanskrit, Computer, Vibhakti, Programming language. -

Arabic Alphabet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Arabic Alphabet from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arabic alphabet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia َأﺑْ َﺠ ِﺪﯾﱠﺔ َﻋ َﺮﺑِﯿﱠﺔ :The Arabic alphabet (Arabic ’abjadiyyah ‘arabiyyah) or Arabic abjad is Arabic abjad the Arabic script as it is codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters. Because letters usually[1] stand for consonants, it is classified as an abjad. Type Abjad Languages Arabic Time 400 to the present period Parent Proto-Sinaitic systems Phoenician Aramaic Syriac Nabataean Arabic abjad Child N'Ko alphabet systems ISO 15924 Arab, 160 Direction Right-to-left Unicode Arabic alias Unicode U+0600 to U+06FF range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0600.pdf) U+0750 to U+077F (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0750.pdf) U+08A0 to U+08FF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U08A0.pdf) U+FB50 to U+FDFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFB50.pdf) U+FE70 to U+FEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFE70.pdf) U+1EE00 to U+1EEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1EE00.pdf) Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. Arabic alphabet ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_alphabet 1/20 2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي History · Transliteration ء Diacritics · Hamza Numerals · Numeration V · T · E (//en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Template:Arabic_alphabet&action=edit) Contents 1 Consonants 1.1 Alphabetical order 1.2 Letter forms 1.2.1 Table of basic letters 1.2.2 Further notes -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Sounds to Graphemes Guide

David Newman – Speech-Language Pathologist Sounds to Graphemes Guide David Newman S p e e c h - Language Pathologist David Newman – Speech-Language Pathologist A Friendly Reminder © David Newmonic Language Resources 2015 - 2018 This program and all its contents are intellectual property. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or reproduced in any way, including but not limited to digital copying and printing without the prior agreement and written permission of the author. However, I do give permission for class teachers or speech-language pathologists to print and copy individual worksheets for student use. Table of Contents Sounds to Graphemes Guide - Introduction ............................................................... 1 Sounds to Grapheme Guide - Meanings ..................................................................... 2 Pre-Test Assessment .................................................................................................. 6 Reading Miscue Analysis Symbols .............................................................................. 8 Intervention Ideas ................................................................................................... 10 Reading Intervention Example ................................................................................. 12 44 Phonemes Charts ................................................................................................ 18 Consonant Sound Charts and Sound Stimulation .................................................... -

Parietal Dysgraphia: Characterization of Abnormal Writing Stroke Sequences, Character Formation and Character Recall

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 99–114 99 IOS Press Parietal dysgraphia: Characterization of abnormal writing stroke sequences, character formation and character recall Yasuhisa Sakuraia,b,∗, Yoshinobu Onumaa, Gaku Nakazawaa, Yoshikazu Ugawab, Toshimitsu Momosec, Shoji Tsujib and Toru Mannena aDepartment of Neurology, Mitsui Memorial Hospital, Tokyo, Japan bDepartment of Neurology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan cDepartment of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Abstract. Objective: To characterize various dysgraphic symptoms in parietal agraphia. Method: We examined the writing impairments of four dysgraphia patients from parietal lobe lesions using a special writing test with 100 character kanji (Japanese morphograms) and their kana (Japanese phonetic writing) transcriptions, and related the test performance to a lesion site. Results: Patients 1 and 2 had postcentral gyrus lesions and showed character distortion and tactile agnosia, with patient 1 also having limb apraxia. Patients 3 and 4 had superior parietal lobule lesions and features characteristic of apraxic agraphia (grapheme deformity and a writing stroke sequence disorder) and character imagery deficits (impaired character recall). Agraphia with impaired character recall and abnormal grapheme formation were more pronounced in patient 4, in whom the lesion extended to the inferior parietal, superior occipital and precuneus gyri. Conclusion: The present findings and a review of the literature suggest that: (i) a postcentral gyrus lesion can yield graphemic distortion (somesthetic dysgraphia), (ii) abnormal grapheme formation and impaired character recall are associated with lesions surrounding the intraparietal sulcus, the symptom being more severe with the involvement of the inferior parietal, superior occipital and precuneus gyri, (iii) disordered writing stroke sequences are caused by a damaged anterior intraparietal area.