Crucifixion in Roman Antiquity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

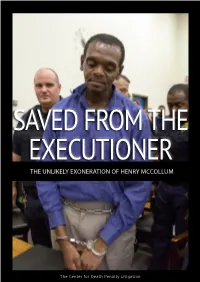

SAVED from the EXECUTIONER: the Unlikely Exoneration of Henry

SAVED FROM THE EXECUTIONER THE UNLIKELY EXONERATION OF HENRY MCCOLLUM The Center for Death Penalty Litigation HENRY MCCOLLUM f all the men and women on death row in North Carolina, Henry McCollum’s guilty verdict looked O airtight. He had signed a confession full of grisly details. Written in crude and unapologetic language, it told the story of four boys, he among them, raping 11-year-old Sabrina Buie, and suffocating her by shoving her own underwear down her throat. He had confessed again in front of television cameras shortly after. His younger brother, Leon Brown, also admitted involvement in the crime. Both were sen- tenced to death in 1984. Leon was later resentenced to life in prison. But Henry remained on death row for 30 years and became Exhibit A in the defense of the death penalty. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia pointed to the brutality of Henry’s crime as a reason to continue capital punishment nation- wide. During North Carolina legislative elections in 2010, Henry’s face showed up on political flyers, the example of a brutal rapist and child killer who deserved to be executed. What almost no one saw — not even his top-notch defense attorneys — was that Henry McCollum was inno- cent. He had nothing to do with Sabrina’s murder. Nor did Leon. In 2014, both were exonerated by DNA evidence and, in 2015, then-Gov. Pat McCrory granted them a rare LEON BROWN pardon of innocence. Though Henry insisted on his innocence for decades, the truth was painfully slow to emerge: Two intellectually disabled teenagers – naive, powerless, and intimidated by a cadre of law enforcement officers – had been pres- sured into signing false confessions. -

Prison Guards and the Death Penalty

BRIEFING PAPER Prison guards and the death penalty Introduction and elsewhere.3 In Japan, in the latter stages before execution, all communication between prisoners or When we think about the people affected by the death between guards and prisoners is forbidden.4 penalty, we may not think about guards on death rows. But these officials, whether they oversee prisoners In 2014, the Texas prison guards union appealed for awaiting execution or participate in the execution itself, better death row prisoner conditions, because the can be deeply affected by their role in helping to put a guards faced daily danger from prisoners made mentally person to death. ill by solitary confinement and who had ‘nothing to lose’.5 In this environment, routine safety practices were imposed that dehumanised prisoners and guards alike, Guards on death row such as every exit of a cell requiring a strip search. Persons sentenced to death are usually considered Guards protested that their own dignity was undermined among the most dangerous prisoners and are placed by the obligation to look at ‘one naked inmate after in the highest security conditions. Prison guards are another’6 all day. frequently suspicious of death row prisoners, are particularly vigilant around them,1 and experience death row as a dangerous place. Interactions with prisoners Despite the stark conditions, death rows are still places Harsh prison conditions can make things worse not where human connections form. In all but the most only for prisoners but also for guards. The mental extreme solitary settings, guards engage with prisoners health of death row prisoners frequently deteriorates regularly, bringing them food and accompanying them and they may suffer from ‘death row phenomenon’, the when they leave their cells (for example to exercise, ‘condition of mental and emotional distress brought on receive visits or attend court hearings). -

Was Jesus Christ Crucified?

ARTICLE of the MONTH December, 2014 WAS JESUS CHRIST CRUCIFIED? The very title of this month's article might strike the reader as one startling question for a Bible-founded Christian fellowship to pose; after all, did not the Apostle Paul plainly write to the congregation at Corinth that, ªI determined not to know any thing among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucifiedºÐI Corinthians 2. 2? Still, in the New World Translation of the Christian Greek Scriptures, published continuously by the Jehovah's Witnesses since 1950 (currently in 2013 revision), the above-quoted verse reads, ªFor I decided not to know anything among you except Jesus Christ, and him executed on the stake.º Similarly, that same translation renders Matthew 10. 38, ªAnd whoever does not accept his torture stake and follow after me is not worthy of me.º Indeed, nowhere in the New World Translation will we find the physical instrument of our Lord's death referred to as a ªcrossº, nor the action itself as a ªcrucifixionºÐthe terms recognised throughout the Christian world. Neither do the Jehovah's Witnesses stand alone in their objection; they, simply, are the largest and most prominent Christian group to make this case. In point of fact, conscientious protest against use of the cross, as a symbol for Jesus's sacrificial death, long pre-dates the 1931 nominate founding of the Jehovah's Witnesses religion: in 1896, e.g., an entire book, The Non-Christian Cross, was published in London; and neither was that the first expressed objection to Christendom's cross. -

{DOWNLOAD} Cross

CROSS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Patterson | 464 pages | 29 Apr 2010 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755349401 | English | London, United Kingdom Cross Pens for Discount & Sales | Last Chance to Buy | Cross The Christian cross , seen as a representation of the instrument of the crucifixion of Jesus , is the best-known symbol of Christianity. For a few centuries the emblem of Christ was a headless T-shaped Tau cross rather than a Latin cross. Elworthy considered this to originate from Pagan Druids who made Tau crosses of oak trees stripped of their branches, with two large limbs fastened at the top to represent a man's arm; this was Thau, or god. John Pearson, Bishop of Chester c. In which there was not only a straight and erected piece of Wood fixed in the Earth, but also a transverse Beam fastened unto that towards the top thereof". There are few extant examples of the cross in 2nd century Christian iconography. It has been argued that Christians were reluctant to use it as it depicts a purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution. The oldest extant depiction of the execution of Jesus in any medium seems to be the second-century or early third-century relief on a jasper gemstone meant for use as an amulet, which is now in the British Museum in London. It portrays a naked bearded man whose arms are tied at the wrists by short strips to the transom of a T-shaped cross. An inscription in Greek on the obverse contains an invocation of the redeeming crucified Christ. -

Justin Martyr, Irenaeus of Lyons, and Cyprian of Carthage on Suffering: A

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY JUSTIN MARTYR, IRENAEUS OF LYONS, AND CYPRIAN OF CARTHAGE ON SUFFERING: A COMPARATIVE AND CRITICAL STUDY OF THEIR WORKS THAT CONCERN THE APOLOGETIC USES OF SUFFERING IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE RAWLINGS SCHOOL OF DIVINITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THEOLOGY AND APOLOGETICS BY AARON GLENN KILBOURN LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA AUGUST 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Aaron Glenn Kilbourn All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL SHEET JUSTIN MARTYR, IRENAEUS OF LYONS, AND CYPRIAN OF CARTHAGE ON SUFFERING: A COMPARATIVE AND CRITICAL STUDY OF THEIR WORKS THA CONCERN THE APOLOGETIC USES OF SUFFERING IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY Aaron Glenn Kilbourn Read and approved by: Chairperson: _____________________________ Reader: _____________________________ Reader: _____________________________ Date: _____________________________ iii To my wife, Michelle, my children, Aubrey and Zack, as well as the congregation of First Baptist Church of Parker, SD. I thank our God that by His grace, your love, faithfulness, and prayers have all helped sustain each of my efforts for His glory. iv CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………………ix Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….x CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………..1 Personal Interest………………………………………………………………………8 The Need for the Study……………………………………………………………….9 Methodological Design……………………………………………………………….10 Limitations……………………………………………………………………………12 CHAPTER 2: THE CONCEPT OF SUFFERING IN THE BIBLE AND EARLY APOLOGISTS........................................................................................................................14 -

Crucifixion in Antiquity: an Inquiry Into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion

GUNNAR SAMUELSSON Crucifixion in Antiquity Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 310 Mohr Siebeck Gunnar Samuelsson questions the textual basis for our knowledge about the death of Jesus. As a matter of fact, the New Testament texts offer only a brief description of the punishment that has influenced a whole world. ISBN 978-3-16-150694-9 Mohr Siebeck Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament · 2. Reihe Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie (Marburg) Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) 310 Gunnar Samuelsson Crucifixion in Antiquity An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion Mohr Siebeck GUNNAR SAMUELSSON, born 1966; 1992 Pastor and Missionary Degree; 1997 B.A. and M.Th. at the University of Gothenburg; 2000 Μ. Α.; 2010 ThD; Senior Lecturer in New Testament Studies at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas and Religion, University of Gothenburg. ISBN 978-3-16-150694-9 ISSN 0340-9570 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 2. Reihe) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ©2011 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Laupp & Göbel in Nehren on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Nadele in Nehren. -

The Spanish Garrote

he members of parliament, meeting in Cadiz in 1812, to draft the first Spanish os diputados reunidos en Cádiz en 1812 para redactar la primera Constitución Constitution, were sensitive to the irrational torment that those condemned to Española, fueron sensibles a los irracionales padecimientos que hasta entonces capital punishment had up until then suffered when they were punished. In De- the spanish garrote sufrían los condenados a la pena capital en el momento de ser ajusticiados, y cree CXXVIII, of 24 January, they recognized that “no punishment will be trans- en el Decreto CXXVIII, de 24 de enero, reconocieron que “ninguna pena ha ferable to the family of the person that suffers it; and wishing at the same time that Lde ser trascendental a la familia del que la sufre; y queriendo al mismo tiempo Tthe torment of the criminals should not offer too repugnant a spectacle to humanity que el suplicio de los delincuentes no ofrezca un espectáculo demasiado and to the generous nature of the Spanish nation (…) ” they agreed to abolish the repugnante a la humanidad y al carácter generoso de la Nación española transferable punishment of hanging, replacing it with the garrote. (...) ” acordaron abolir la trascendental pena de horca, sustituyéndola por la Some days earlier, on January 10th, the City Council of Toledo, in compliance de garrote. with a decision of the Real Junta Criminal [Royal Criminal Committee] of the city, Ya unos días antes, el 10 de enero, el ayuntamiento de Toledo, en cum- agreed to the construction of two garrotes and approved the regulations for the plimiento de una providencia de la Real Junta Criminal de la ciudad, acordó construction of the platform. -

Biblical Perspectives on Torture: War Crime, the Limits of Retaliation, And

The Asbury Journal 64/2:4-11 © 2009 Asbury Theological Seminary BILL T. ARNOLD Biblical Perspectives on Torture: War the Lzmzts of RetaliatIOn, and the Roman Cross Our concept of "torture" has a narrow and generally accepted definition as the "infliction of severe bodily pain, as punishment or a means of persuasion."1 The Bible has no exact equivalent, and if we limit our discussion to this definition, we might too quickly conclude the Bible has little if anything to say directly about torture. This is so because the Bible's lexical specifics have broader connotations. Words translated "oppress" or "torment" have semantic domains close to our meaning of "torture," but not precisely equivalent.2 Thus the standard Bible dictionaries and encyclopedias are more likely to have entries on "crime and punishment" than "torture," and these have quite different themes to cover. On the other hand, ifwe define "torture" as the use of excessive physical or mental pain against one's enemy combatant or against innocent victims of armed conflict - what we might today call "war crimes" - then the Bible has plenty to say about this topic. Although the Old Testament does not contain large numbers of texts for us to consider, it has important passages in Deuteronomy and Amos pertinent to this theme, as well as scattered texts in the legal corpora. The New Testament, of course, presents the most vivid symbol of torture in human history in the form of the Roman crosS. The Old Testament contains passages that reflect the horrors of wartime torture, especially by prohibiting Israel from engaging in such inhumane acts or in condemning such actions in Israel's neighbors.3 The most important of these texts comes from the book of Deuteronomy, which establishes (1) rules for conducting the war of conquest, when Israel entered the Promised Land and defeated the seven nations (sometimes six are listed) inhabiting the land (Deut 7: 1-26), as well as (2) rules for ordinary warfare conducted after the settlement against enemies outside the Promised Land (Deut 20: 1-20; 21: 10- 14, and cf. -

The Peformative Grotesquerie of the Crucifixion of Jesus

THE GROTESQUE CROSS: THE PERFORMATIVE GROTESQUERIE OF THE CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS Hephzibah Darshni Dutt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Charles Kanwischer Graduate Faculty Representative Eileen Cherry Chandler Marcus Sherrell © 2015 Hephzibah Dutt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In this study I argue that the crucifixion of Jesus is a performative event and this event is an exemplar of the Grotesque. To this end, I first conduct a dramatistic analysis of the crucifixion of Jesus, working to explicate its performativity. Viewing this performative event through the lens of the Grotesque, I then discuss its various grotesqueries, to propose the concept of the Grotesque Cross. As such, the term “Grotesque Cross” functions as shorthand for the performative event of the crucifixion of Jesus, as it is characterized by various aspects of the Grotesque. I develop the concept of the Grotesque Cross thematically through focused studies of representations of the crucifixion: the film, Jesus of Montreal (Arcand, 1989), Philip Turner’s play, Christ in the Concrete City, and an autoethnographic examination of Cross-wearing as performance. I examine each representation through the lens of the Grotesque to define various facets of the Grotesque Cross. iv For Drs. Chetty and Rukhsana Dutt, beloved holy monsters & Hannah, Abhishek, and Esther, my fellow aliens v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in instructing catechumens, wrote, “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. -

Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 "Thus Did God Break the Head of that Leviathan": Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England Ian Edward Tonat College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Tonat, Ian Edward, ""Thus Did God Break the Head of that Leviathan": Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626765. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ycqh-3b72 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Thus Did God Break the Head of That Leviathan”: Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth- Century New England Ian Edward Tonat Gaithersburg, Maryland Bachelor of Arts, Carleton College, 2011 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted -

Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by St. John's University School of Law St. John's Law Review Volume 75 Number 3 Volume 75, Summer 2001, Number 3 Article 4 March 2012 Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row Norman L. Greene Governor George H. Ryan Donald Cabana Jim Dwyer Martha Barnett See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Greene, Norman L.; Ryan, Governor George H.; Cabana, Donald; Dwyer, Jim; Barnett, Martha; and Davis, Evan (2001) "Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row," St. John's Law Review: Vol. 75 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol75/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row Authors Norman L. Greene, Governor George H. Ryan, Donald Cabana, Jim Dwyer, Martha Barnett, and Evan Davis This article is available in St. John's Law Review: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol75/iss3/4 GOVERNOR RYAN'S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT MORATORIUM AND THE EXECUTIONER'S CONFESSION: VIEWS FROM THE GOVERNOR'S MANSION TO DEATH ROW NORMAN L. -

Death Row Witness Reveals Inmates' Most Chilling Final Moments

From bloodied shirts and shuddering to HEADS on fire: Death Row witness reveals inmates' most chilling final moments By: Chris Kitching - Mirror Online Ron Word has watched more than 60 Death Row inmates die for their brutal crimes - and their chilling final moments are likely to stay with him until he takes his last breath. Twice, he looked on in horror as flames shot out of a prisoner's head - filling the chamber with smoke - when a hooded executioner switched on an electric chair called "Old Sparky". Another time, blood suddenly appeared on a convicted murderer's white shirt, caking along the leather chest strap holding him to the chair, as electricity surged through his body. Mr Word was there for another 'botched' execution, when two full doses of lethal drugs were needed to kill an inmate - who shuddered, blinked and mouthed words for 34 minutes before he finally died. And then there was the case of US serial killer Ted Bundy, whose execution in 1989 drew a "circus" outside Florida State Prison and celebratory fireworks when it was announced that his life had been snuffed out. Inside the execution chamber at the Florida State Prison near Starke (Image: Florida Department of Corrections/Doug Smith) 1 of 19 The electric chair at the prison was called "Old Sparky" (Image: Florida Department of Corrections) Ted Bundy was one of the most notorious serial killers in recent history (Image: www.alamy.com) Mr Word witnessed all of these executions in his role as a journalist. Now retired, the 67-year-old was tasked with serving as an official witness to state executions and reporting what he saw afterwards for the Associated Press in America.