Ambiguity Aversion in Qualitative Contexts: a Vignette Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Task-Based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization

A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display 2 Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display The Human 3 Three kinds of limitations: humans • Human vision ️ has limitations • Human reasoning 易 has limitations The Human 4 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation 5 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation Color perception 6 易 Cognitive bias Behaviors when humans consistently behave irrationally Pohl’s criteria distilled: • Are predictable and consistent • People are unaware they’re doing them • Are not misunderstandings 7 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, -

MITIGATING COGNITIVE BIASES in RISK IDENTIFICATION: Practitioner Checklist for the AEROSPACE SECTOR

MITIGATING COGNITIVE BIASES IN RISK IDENTIFICATION: Practitioner Checklist for the AEROSPACE SECTOR Debra L. Emmons, Thomas A. Mazzuchi, Shahram Sarkani, and Curtis E. Larsen This research contributes an operational checklist for mitigating cogni- tive biases in the aerospace sector risk management process. The Risk Identification and Evaluation Bias Reduction Checklist includes steps for grounding the risk identification and evaluation activities in past project experiences through historical data, and emphasizes the importance of incorporating multiple methods and perspectives to guard against optimism and a singular project instantiation-focused view. The authors developed a survey to elicit subject matter expert judgment on the value of the check- list to support its use in government and industry as a risk management tool. The survey also provided insights on bias mitigation strategies and lessons learned. This checklist addresses the deficiency in the literature in providing operational steps for the practitioner to recognize and implement strategies for bias reduction in risk management in the aerospace sector. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22594/dau.16-770.25.01 Keywords: Risk Management, Optimism Bias, Planning Fallacy, Cognitive Bias Reduction Mitigating Cognitive Biases in Risk Identification http://www.dau.mil January 2018 This article and its accompanying research contribute an operational FIGURE 1. RESEARCH APPROACH Risk Identification and Evaluation Bias Reduction Checklist for cognitive bias mitigation in risk management for the aerospace sector. The checklist Cognitive Biases & Bias described herein offers a practical and implementable project management Enabling framework to help reduce biases in the aerospace sector and redress the Conditions cognitive limitations in the risk identification and analysis process. -

Communication Science to the Public

David M. Berube North Carolina State University ▪ HOW WE COMMUNICATE. In The Age of American Unreason, Jacoby posited that it trickled down from the top, fueled by faux-populist politicians striving to make themselves sound approachable rather than smart. (Jacoby, 2008). EX: The average length of a sound bite by a presidential candidate in 1968 was 42.3 seconds. Two decades later, it was 9.8 seconds. Today, it’s just a touch over seven seconds and well on its way to being supplanted by 140/280- character Twitter bursts. ▪ DATA FRAMING. ▪ When asked if they truly believe what scientists tell them, NEW ANTI- only 36 percent of respondents said yes. Just 12 percent expressed strong confidence in the press to accurately INTELLECTUALISM: report scientific findings. ▪ ROLE OF THE PUBLIC. A study by two Princeton University researchers, Martin TRENDS Gilens and Benjamin Page, released Fall 2014, tracked 1,800 U.S. policy changes between 1981 and 2002, and compared the outcome with the expressed preferences of median- income Americans, the affluent, business interests and powerful lobbies. They concluded that average citizens “have little or no independent influence” on policy in the U.S., while the rich and their hired mouthpieces routinely get their way. “The majority does not rule,” they wrote. ▪ Anti-intellectualism and suspicion (trends). ▪ Trump world – outsiders/insiders. ▪ Erasing/re-writing history – damnatio memoriae. ▪ False news. ▪ Infoxication (CC) and infobesity. ▪ Aggregators and managed reality. ▪ Affirmation and confirmation bias. ▪ Negotiating reality. ▪ New tribalism is mostly ideational not political. ▪ Unspoken – guns, birth control, sexual harassment, race… “The amount of technical information is doubling every two years. -

Cognitive Biases in Software Engineering: a Systematic Mapping Study

Cognitive Biases in Software Engineering: A Systematic Mapping Study Rahul Mohanani, Iflaah Salman, Burak Turhan, Member, IEEE, Pilar Rodriguez and Paul Ralph Abstract—One source of software project challenges and failures is the systematic errors introduced by human cognitive biases. Although extensively explored in cognitive psychology, investigations concerning cognitive biases have only recently gained popularity in software engineering research. This paper therefore systematically maps, aggregates and synthesizes the literature on cognitive biases in software engineering to generate a comprehensive body of knowledge, understand state of the art research and provide guidelines for future research and practise. Focusing on bias antecedents, effects and mitigation techniques, we identified 65 articles (published between 1990 and 2016), which investigate 37 cognitive biases. Despite strong and increasing interest, the results reveal a scarcity of research on mitigation techniques and poor theoretical foundations in understanding and interpreting cognitive biases. Although bias-related research has generated many new insights in the software engineering community, specific bias mitigation techniques are still needed for software professionals to overcome the deleterious effects of cognitive biases on their work. Index Terms—Antecedents of cognitive bias. cognitive bias. debiasing, effects of cognitive bias. software engineering, systematic mapping. 1 INTRODUCTION OGNITIVE biases are systematic deviations from op- knowledge. No analogous review of SE research exists. The timal reasoning [1], [2]. In other words, they are re- purpose of this study is therefore as follows: curring errors in thinking, or patterns of bad judgment Purpose: to review, summarize and synthesize the current observable in different people and contexts. A well-known state of software engineering research involving cognitive example is confirmation bias—the tendency to pay more at- biases. -

Mitigating Cognitive Biases in Risk Identification

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20190025941 2019-08-31T14:18:02+00:00Z View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NASA Technical Reports Server Mitigating Cognitive Biases in Risk Identification: Practitioner Checklist for the Aerospace Sector Debra Emmons, Thomas A. Mazzuchi, Shahram Sarkani, and Curtis E. Larsen This research contributes an operational checklist for mitigating cognitive biases in the aerospace sector risk management process. The Risk Identification and Evaluation Bias Reduction Checklist includes steps for grounding the risk identification and evaluation activities in past project experiences, through historical data, and the importance of incorporating multiple methods and perspectives to guard against optimism and a singular project instantiation focused view. The authors developed a survey to elicit subject matter expert (SME) judgment on the value of the checklist to support its use in government and industry as a risk management tool. The survey also provided insights on bias mitigation strategies and lessons learned. This checklist addresses the deficiency in the literature in providing operational steps for the practitioner for bias reduction in risk management in the aerospace sector. Two sentence summary: Cognitive biases such as optimism, planning fallacy, anchoring and ambiguity effect influence the risk identification and analysis processes used in the aerospace sector at the Department of Defense, other government organizations, and industry. This article incorporates practical experience through subject matter expert survey feedback into an academically grounded operational checklist and offers strategies for the project manager and risk management practitioner to reduce these pervasive biases. MITIGATING COGNITIVE BIASES IN RISK IDENTIFICATION Keywords: risk management; optimism bias; planning fallacy; cognitive bias reduction The research began with the review of the literature, which covered the areas of risk management, cognitive biases and bias enabling conditions. -

50 Cognitive and Affective Biases in Medicine (Alphabetically)

50 Cognitive and Affective Biases in Medicine (alphabetically) Pat Croskerry MD, PhD, FRCP(Edin), Critical Thinking Program, Dalhousie University Aggregate bias: when physicians believe that aggregated data, such as those used to develop clinical practice guidelines, do not apply to individual patients (especially their own), they are exhibiting the aggregate fallacy. The belief that their patients are atypical or somehow exceptional, may lead to errors of commission, e.g. ordering x-rays or other tests when guidelines indicate none are required. Ambiguity effect: there is often an irreducible uncertainty in medicine and ambiguity is associated with uncertainty. The ambiguity effect is due to decision makers avoiding options when the probability is unknown. In considering options on a differential diagnosis, for example, this would be illustrated by a tendency to select options for which the probability of a particular outcome is known over an option for which the probability is unknown. The probability may be unknown because of lack of knowledge or because the means to obtain the probability (a specific test, or imaging) is unavailable. The cognitive miser function (choosing an option that requires less cognitive effort) may also be at play here. Anchoring: the tendency to perceptually lock on to salient features in the patient’s initial presentation too early in the diagnostic process, and failure to adjust this initial impression in the light of later information. This bias may be severely compounded by the confirmation bias. Ascertainment bias: when a physician’s thinking is shaped by prior expectation; stereotyping and gender bias are both good examples. Attentional bias: the tendency to believe there is a relationship between two variables when instances are found of both being present. -

1 Embrace Your Cognitive Bias

1 Embrace Your Cognitive Bias http://blog.beaufortes.com/2007/06/embrace-your-co.html Cognitive Biases are distortions in the way humans see things in comparison to the purely logical way that mathematics, economics, and yes even project management would have us look at things. The problem is not that we have them… most of them are wired deep into our brains following millions of years of evolution. The problem is that we don’t know about them, and consequently don’t take them into account when we have to make important decisions. (This area is so important that Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel Prize in 2002 for work tying non-rational decision making, and cognitive bias, to mainstream economics) People don’t behave rationally, they have emotions, they can be inspired, they have cognitive bias! Tying that into how we run projects (project leadership as a compliment to project management) can produce results you wouldn’t believe. You have to know about them to guard against them, or use them (but that’s another article)... So let’s get more specific. After the jump, let me show you a great list of cognitive biases. I’ll bet that there are at least a few that you haven’t heard of before! Decision making and behavioral biases Bandwagon effect — the tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. Related to groupthink, herd behaviour, and manias. Bias blind spot — the tendency not to compensate for one’s own cognitive biases. Choice-supportive bias — the tendency to remember one’s choices as better than they actually were. -

24 Days of December, 24 Cognitive Biases That Distort the Way You View the World

24 days of December, 24 Cognitive biases that distort the way you view the world Being human is being biased. But while many biases make evolutionary sense, they cloud our judgment and reduce our ability to make rational and reflected decisions. And furthermore, cognitive biases often contribute to reducing diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Being aware of your own biases as they occur, will help you to control and manage them actively. And thereby help you make better decisions. And ultimately you will foster an environment that is more diverse and inclusive. For each day of December, I will open the window to a new cognitive bias so that you may learn and perhaps be inspired to manage your own cognitive distortion. December 1. Ambiguity effect. Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t. The ambiguity effect refers to the human bias towards preferring the well-known option to the less well-known option. This bias makes a lot of evolutionary sense (“eat only the berries you know because then you know they won’t kill you) but in modern society and business, it also predisposes leaders to prefer people that look and act like someone they already know. A bias to beware of and manage carefully as it is a foe of diversity. Read more https://medium.com/@michaelgearon/cognitive-biases-ambiguity-effect-e0fe2c213061 December 2. Backfire effect; Ever tried arguing with someone online? Then you have probably experienced the backfire effect. It is the flipside of the confirmation bias (see my update from December 4) – and it describes the phenomenon when someone “digs in their feet” in an argument rather than actually listening and trying to understand the other side. -

Asymmetric Responses to Earnings News: a Case for Ambiguity

Asymmetric Responses to Earnings News: A Case for Ambiguity Christopher D. Williams A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Kenan-Flagler Business School. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Robert M. Bushman Wayne R. Landsman Jennifer Conrad Mark Lang Steve Stubben Abstract Christopher D. Williams: Asymmetric Responses to Earnings News: A Case for Ambiguity (Under the direction of Robert M. Bushman and Wayne R. Landsman) In this paper I empirically investigate whether investors change the way they respond to earnings releases following changes in “ambiguity” in a manner consistent with extant research that distinguishes risk from ambiguity. With risk, decision-makers possess known probabilities and formulate unique prior distributions over all possible outcomes. In contrast, with ambiguity, decision-makers possess incomplete knowledge about probabilities and are unable to formulate priors over all possible outcomes. Existing theoretical research supports the hypothesis that investors respond differentially to good versus bad news information releases when confronted with ambiguity. As a proxy for ambiguity I use the volatility index (VIX). I provide evidence that following increases in VIX investors respond asymmetrically, weighting bad earnings news more than good earnings news. Conversely, following a decrease in VIX investors respond symmetrically to good and bad earnings news. Results are robust to consideration of both risk and investor sentiment explanations. I also document that the effect of ambiguity is intensified for firms with a high systematic component to earnings, and is mitigated for firms with high trading volume over the event window. -

A Simple Handbook for Non-Traditional Red Teaming

UNCLASSIFIED A Simple Handbook for Non-Traditional Red Teaming Monique Kardos* and Patricia Dexter Joint and Operations Analysis Division *National Security and ISR Division Defence Science and Technology Group DST-Group-TR-3335 ABSTRACT This report represents a guide for those wishing to apply red teaming methods in a structured manner, and provides lessons developed in both the military and national security environments. It describes the practice of red teaming in the context of biases and heuristics followed by techniques and activity designs allowing others to design and apply red teaming activities across a range of domains. RELEASE LIMITATION Approved for public release UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Produced by Joint & Operations Analysis Division DST Group Edinburgh PO BOX 1500, Edinburgh, SA, 5111 Telephone: 1300 333 362 Commonwealth of Australia 2017 January 2017 AR-016-782 Conditions of Release and Disposal This document is the property of the Australian Government; the information it contains is released for defence and national security purposes only and must not be disseminated beyond the stated distribution without prior approval of the Releasing Authority. The document and the information it contains must be handled in accordance with security regulations, downgrading and delimitation is permitted only with the specific approval of the Releasing Authority. This information may be subject to privately owned rights. The officer in possession of this document is responsible for its safe custody. UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED A Simple Handbook for Non-Traditional Red Teaming Executive Summary This report describes the application of red teaming as a methodology in a broader, less traditional sense. It is designed to enable people to employ a more analytical approach to their problem analysis or evaluations, and to tailor the scale and complexity of red teaming activities to meet their specific needs. -

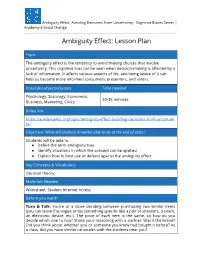

Ambiguity Effect

Ambiguity Effect: Avoiding Decisions From Uncertainty - Cognitive Biases Series | Academy 4 Social Change Ambiguity Effect: Lesson Plan Topic The ambiguity effect is the tendency to avoid making choices that involve uncertainty. This cognitive bias can be seen when decision-making is affected by a lack of information. It affects various aspects of life, and being aware of it can help us become more informed consumers, presenters, and voters. Possible subjects/classes Time needed Psychology, Sociology, Economics, 30-35 minutes Business, Marketing, Civics Video link: https://academy4sc.org/topic/ambiguity-effect-avoiding-decisions-from-uncertain ty/ Objective: What will students know/be able to do at the end of class? Students will be able to... ● Define the term ambiguity bias. ● Identify situations in which the concept can be applied. ● Explain how to best use or defend against the ambiguity effect. Key Concepts & Vocabulary Decision theory Materials Needed Worksheet, Student Internet Access Before you watch Turn & Talk: You’re at a store deciding between purchasing two similar items (you can leave this vague or list something specific like a pair of sneakers, a snack, an electronic device, etc.). The price of each item is the same, so how do you decide which one to buy? Share your reasoning with a partner. Was it the brand? Did you think about whether you or someone you know had bought it before? As a class, did you have similar rationales with the students near you? Ambiguity Effect: Avoiding Decisions From Uncertainty - Cognitive Biases Series | Academy 4 Social Change While you watch 1. Define the ambiguity effect. -

Examining Financial Puzzles from an Evolutionary Perspective

Examining Financial Puzzles From An Evolutionary Perspective by Kenrick Guo B.S. Industrial Engineering Nrnrt1hxxpltp.rnI IVLLI **V~VII T I1nivr *V+LIL-- itv ·-9)()Ui V- SUBMITTED TO THE SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN OPERATIONS RESEARCH I~ AT THE b~~ MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 2006 © 2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved Author................................................................................. ............................. Sloan School of Management f1 November 10, 2005 Certified by ......... .............................. _ ....... ................ .. Andrew W. Lo Harris & Harris Group Professor, Sloan School of Management Thesis Supervisor Acceptedby ................ ......... ................................................. James B. Orlin Co-Director, Operations Research Center Examining Financial Puzzles From An Evolutionary Perspective by Kenrick Guo Submitted to the Sloan School of Management on November 10, 2005, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Operations Research Abstract In this thesis, we examine some puzzles in finance from an evolutionary perspective. We first provide a literature review of evolutionary psychology, and discuss three main findings; the frequentist hypothesis, applications from risk-sensitive optimal foraging theory, and the cheater detection hypothesis. Next we introduce some of the most-researched puzzles in the finance literature. Examples include overreaction, loss aversion, and the equity premium puzzle. Following this, we discuss risk-sensitive optimal foraging theory further and examine some of the financial puzzles using the framework of risk-sensitive foraging. Finally, we develop a dynamic patch selection model which gives the patch selection strategy that maximizes an organism's long-run probability of survival. It is from this optimal patch strategy that we observe loss aversion.