Mojave National Preserve & U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5. Consultation and Collaboration

Draft Environmental Impact Statement Diamond Project Plumas National Forest Chapter 5. Consultation and Collaboration 5.1 Preparers and Contributors_____________________________ The Forest Service consulted the following individuals; federal, state, and local agencies; and tribes during the development of this environmental impact statement (EIS): 5.1.1 Interdisciplinary Team Members Name Title Education / Responsibility / Experience Merri Carol Martens Planner Merri Carol has a B.S. degree in Forestry from West Virginia University. She has 15 years of experience in natural resource management with the U.S. Forest Service. Chris Collins Wildlife Chris holds a B.S. degree in Wildlife Management from Biologist Humboldt State University. He has 13 years of experience in wildlife management and biological work with the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Chris is responsible for project coordination, planning, implementation, and monitoring for wildlife issues on the Mt. Hough Ranger District. Michelle Coppoletta Botanist Michelle received a B.S. degree in Plant Biology from the University of California at Berkeley and a Master of Science in Ecology from the University of California at Davis. Prior to working with the Forest Service, Michelle was a rare plant botanist for the National Park Service at Point Reyes National Seashore where she worked on developing conservation and management plans for rare and sensitive plant species. She has also worked as a biological science technician for the USGS in the southern Sierra Nevada. She is currently the assistant botanist on the Mt. Hough Ranger District of the Plumas National Forest. Cristina Weinberg Archaeologist Christina has a B.A. -

Sharing the Range: Managing Wildlife Impacts to Livestock Production in California Coast Range Working Landscapes Author Sheri Spiegal Ph.D

Title Sharing the range: managing wildlife impacts to livestock production in California Coast Range working landscapes Author Sheri Spiegal Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management University of California, Berkeley Abstract Livestock and wildlife share grazed rangelands, and in many cases, they get along fine. Some wildlife species, however, can negatively impact livestock operations by killing livestock, consuming forage, damaging facilities, and transmitting disease. Ranchers have traditionally resorted to lethal wildlife control to reduce these impacts, yet this has been controversial as many people do not want any animal to be harmed for any reason. In addition, some policies designed to protect wildlife may be perceived by ranchers as doing so at the expense of livestock production. It is important to find ways to minimize the conflicts between livestock production and wildlife protection in order to maintain sustainable working landscapes that enjoy broad support among livestock producers and conservationists. Interviews of people connected with livestock production in and adjacent to the California Coast Ranges, from Mendocino County south to Monterey County, and a review of scientific literature were used to identify the main problems ranchers experience with wildlife and the impact reduction strategies they use that are broadly acceptable to the public. Interviewees most commonly described grievances related to the mountain lion, tule elk, coyote, California ground squirrel, and feral pig. For each of these species, a history of popular opinion in California is summarized, ecological and biological characteristics are briefly reviewed, impacts to livestock operations are described, dimensions of lethal control are outlined, and strategies used to reduce impacts with minimal controversy are assessed for their effectiveness. -

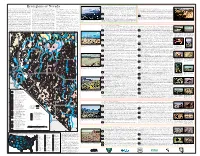

M O J a V E D E S E R T I S S U E S a Secondary

MOJAVE DESERT ISSUES A Secondary School Curriculum Bruce W. Bridenbecker & Darleen K. Stoner, Ph.D. Research Assistant Gail Uchwat Mojave Desert Issues was funded with a grant from the National Park �� Foundation. Parks as Classrooms is the educational program of the National ����� �� ���������� Park Service in partnership with the National Park Foundation. Design by Amy Yee and Sandra Kaye Published in 1999 and printed on recycled paper ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following people for their contribution to this work: Elayn Briggs, Bureau of Land Management Caryn Davidson, National Park Service Larry Ellis, Banning High School Lorenza Fong, National Park Service Veronica Fortun, Bureau of Land Management Corky Hays, National Park Service Lorna Lange-Daggs, National Park Service Dave Martell, Pinon Mesa Middle School David Moore, National Park Service Ruby Newton, National Park Service Carol Peterson, National Park Service Pete Ricards, Twentynine Palms Highschool Kay Rohde, National Park Service Dennis Schramm, National Park Service Jo Simpson, Bureau of Land Management Kirsten Talken, National Park Service Cindy Zacks, Yucca Valley Highschool Joe Zarki, National Park Service The following specialists provided information: John Anderson, California Department of Fish & Game Dave Bieri, National Park Service �� John Crossman, California Department of Parks and Recreation ����� �� ���������� Don Fife, American Land Holders Association Dana Harper, National Park Service Judy Hohman, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Becky Miller, California -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Two New Species of Cephalobidae from Valle De La Luna, Argentina, and Observations on the Genera Acrobeles and Nothacrobeles (Nematoda: Rhabditida)

Fundarn. appl. NernalOl., 1997,20 (4), 329-347 Two new species of Cephalobidae from Valle de la Luna, Argentina, and observations on the genera Acrobeles and Nothacrobeles (Nematoda: Rhabditida) Fayyaz SHAHINA* and Paul DE LEY* International Institute ofParasitology, 395a Hatfield Raad, St Albans, Herts AL4 OXU, England. Accepted for publication 5 August 1996. SUD1D1ary - Acrobeles emmatus sp. n. and Nochacrobeles lunensis sp. n. are described from a desert valley in Argentina. A. ernmatus sp. n. is distinct from ail known species of the genus in having an "inner layer" of the cuticle undulating twice per annule. N. lunensis sp. n. is distinct from ail other species of the genus in having a "double cuticle" as in Seleborca and Triligulla. We argue mat this type of cuticular structure must have arisen independently in at least three separate lineages, and mat it is insufficient as a genus character. Seleborca is therefore synonymized with Acrobeles, and Triligulla with Cervidellus. A single male of Nochacrobeles cf. subtilis is also described. Ir has minute tines on the probolae and a lateral field changing from four lines anteriorly to three lines posteriorly. We consider this to invalidate the genus Namibinema, which is merefore synonymized with Nochacrobeles. Tables of specifie differential characters are given to the re-defined genera Acrobeles and Nochacrobeles. RéSUD1é - Deux espèces nouvelles de Cephalobidae provenant de la Vallèe de la Lune, Argentine, et observations sur les genres Acrobeles et Nothacrobeles (Nematoda: Rhabditida) - Description est donnée d'Acrobeles emmatus sp. n. et de Nochacrobeles lunensis sp. n. provenant d'une vallée désertique d'Argentine. -

Appendix F3 Rare Plant Survey Report

Appendix F3 Rare Plant Survey Report Draft CADIZ VALLEY WATER CONSERVATION, RECOVERY, AND STORAGE PROJECT Rare Plant Survey Report Prepared for May 2011 Santa Margarita Water District Draft CADIZ VALLEY WATER CONSERVATION, RECOVERY, AND STORAGE PROJECT Rare Plant Survey Report Prepared for May 2011 Santa Margarita Water District 626 Wilshire Boulevard Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90017 213.599.4300 www.esassoc.com Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego San Francisco Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills D210324 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cadiz Valley Water Conservation, Recovery, and Storage Project: Rare Plant Survey Report Page Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................2 Objective .......................................................................................................................... 2 Project Location and Description .....................................................................................2 Setting ................................................................................................................................... 5 Climate ............................................................................................................................. 5 Topography and Soils ......................................................................................................5 -

Nectary Use for Gaining Access to an Ant Host by the Parasitoid Orasema Simulatrix (Hymenoptera, Eucharitidae)

JHR 27: 47–65Nectary (2012) use for gaining access to an ant host by the parasitoid Orasema simulatrix... 47 doi: 10.3897/JHR.27.3067 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.pensoft.net/journals/jhr Nectary use for gaining access to an ant host by the parasitoid Orasema simulatrix (Hymenoptera, Eucharitidae) Bryan Carey1, Kirk Visscher2, John Heraty2 1 Department of Life Sciences, El Camino College, Torrance, CA 90506 2 Department of Entomology, Uni- versity of California, Riverside, CA 92521 Corresponding author: John Heraty ([email protected]) Academic editor: Mark Shaw | Received 12 March 2012 | Accepted 9 May 2012 | Published 31 May 2012 Citation: Carey B, Visscher K, Heraty J (2012) Nectary use for gaining access to an ant host by the parasitoid Orasema simulatrix (Hymenoptera, Eucharitidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research 27: 47–65. doi: 10.3897/JHR.27.3067 Abstract Eucharitidae is the only family of insects known to specialize as parasitoids of ant brood. Eggs are laid away from the host onto or in plant tissue, and the minute first-instars (planidia) are responsible for gain- ing access to the host through some form of phoretic attachment to the host ant or possibly through an intermediate host such as thrips. Orasema simulatrix (Eucharitidae: Oraseminae) are shown to deposit their eggs into incisions made on leaves of Chilopsis linearis (Bignoniaceae) in association with extrafloral nectaries (EFN). Nectary condition varies from fluid-filled on the newest leaves, to wet or dry nectaries on older leaves. Filled nectaries were about one third as common as dry nectaries, but were three times as likely to have recent oviposition. -

Luth Wfu 0248D 10922.Pdf

SCALE-DEPENDENT VARIATION IN MOLECULAR AND ECOLOGICAL PATTERNS OF INFECTION FOR ENDOHELMINTHS FROM CENTRARCHID FISHES BY KYLE E. LUTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADAUTE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Biology May 2016 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Gerald W. Esch, Ph.D., Advisor Michael V. K. Sukhdeo, Ph.D., Chair T. Michael Anderson, Ph.D. Herman E. Eure, Ph.D. Erik C. Johnson, Ph.D. Clifford W. Zeyl, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my PI, Dr. Gerald Esch, for all of the insight, all of the discussions, all of the critiques (not criticisms) of my works, and for the rides to campus when the North Carolina weather decided to drop rain on my stubborn head. The numerous lively debates, exchanges of ideas, voicing of opinions (whether solicited or not), and unerring support, even in the face of my somewhat atypical balance of service work and dissertation work, will not soon be forgotten. I would also like to acknowledge and thank the former Master, and now Doctor, Michael Zimmermann; friend, lab mate, and collecting trip shotgun rider extraordinaire. Although his need of SPF 100 sunscreen often put our collecting trips over budget, I could not have asked for a more enjoyable, easy-going, and hard-working person to spend nearly 2 months and 25,000 miles of fishing filled days and raccoon, gnat, and entrail-filled nights. You are a welcome camping guest any time, especially if you do as good of a job attracting scorpions and ants to yourself (and away from me) as you did on our trips. -

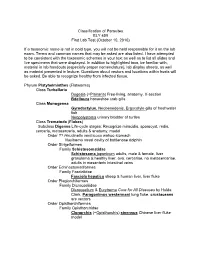

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Synoptic-Scale Control Over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates

JUNE 2018 ARMONETAL. 1077 Synoptic-Scale Control over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates MOSHE ARMON Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel ELAD DENTE Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, and Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel JAMES A. SMITH Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey YEHOUDA ENZEL AND EFRAT MORIN Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel (Manuscript received 23 January 2018, in final form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT Rainfall in the Levant drylands is scarce but can potentially generate high-magnitude flash floods. Rainstorms are caused by distinct synoptic-scale circulation patterns: Mediterranean cyclone (MC), active Red Sea trough (ARST), and subtropical jet stream (STJ) disturbances, also termed tropical plumes (TPs). The unique spatiotemporal char- acteristics of rainstorms and floods for each circulation pattern were identified. Meteorological reanalyses, quantitative precipitation estimates from weather radars, hydrological data, and indicators of geomorphic changes from remote sensing imagery were used to characterize the chain of hydrometeorological processes leading to distinct flood patterns in the region. Significant differences in the hydrometeorology of these three flood-producing synoptic systems were identified: MC storms draw moisture from the Mediterranean and generate moderate rainfall in the northern part of the region. ARST and TP storms transfer large amounts of moisture from the south, which is converted to rainfall in the hyperarid southernmost parts of the Levant. -

Worms, Nematoda

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2001 Worms, Nematoda Scott Lyell Gardner University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Gardner, Scott Lyell, "Worms, Nematoda" (2001). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Volume 5 (2001): 843-862. Copyright 2001, Academic Press. Used by permission. Worms, Nematoda Scott L. Gardner University of Nebraska, Lincoln I. What Is a Nematode? Diversity in Morphology pods (see epidermis), and various other inverte- II. The Ubiquitous Nature of Nematodes brates. III. Diversity of Habitats and Distribution stichosome A longitudinal series of cells (sticho- IV. How Do Nematodes Affect the Biosphere? cytes) that form the anterior esophageal glands Tri- V. How Many Species of Nemata? churis. VI. Molecular Diversity in the Nemata VII. Relationships to Other Animal Groups stoma The buccal cavity, just posterior to the oval VIII. Future Knowledge of Nematodes opening or mouth; usually includes the anterior end of the esophagus (pharynx). GLOSSARY pseudocoelom A body cavity not lined with a me- anhydrobiosis A state of dormancy in various in- sodermal epithelium. -

Climate Change Impacts on California Vegetation: Physiology, Life History, and Ecosystem Change

CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON CALIFORNIA VEGETATION: PHYSIOLOGY, LIFE HISTORY, AND ECOSYSTEM CHANGE A White Paper from the California Energy Commission’s California Climate Change Center Prepared for: California Energy Commission Prepared by: University of California, Berkeley JULY 2012 CEC‐500‐2012‐023 William K. Cornwell1,2 Stephanie A. Stuart3 Aaron Ramirez1 Christopher R. Dolanc4 James H. Thorne4 David D. Ackerly1 1University of California, Berkeley 2 Vrije University, Netherlands 3Macquarie University, Australia 4University of California, Davis DISCLAIMER This paper was prepared as the result of work sponsored by the California Energy Commission. It does not necessarily represent the views of the Energy Commission, its employees or the State of California. The Energy Commission, the State of California, its employees, contractors and subcontractors make no warrant, express or implied, and assume no legal liability for the information in this paper; nor does any party represent that the uses of this information will not infringe upon privately owned rights. This paper has not been approved or disapproved by the California Energy Commission nor has the California Energy Commission passed upon the accuracy or adequacy of the information in this paper. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements are provided in each section of this paper. i ABSTRACT Dominant plant species mediate many ecosystem services, including carbon storage, soil retention, and water cycling. One of the uncertainties with climate change effects on terrestrial ecosystems is understanding where transitions in dominant vegetation, often termed state change, will occur. The complex nature of state change requires multiple lines of evidence. Here, we present four lines of inquiry into climate change effects on dominant vegetation, focusing on the likelihood and nature of climate change–driven state change.