Published Version (1.475Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Annual Report 2015 LETTER to MINISTER

Annual Report 2015 LETTER TO MINISTER 23 February 2016 The Honourable Annastacia Palaszczuk MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Level 15, Executive Building 100 George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Premier I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2015 and audited financial statements for the Queensland Theatre Company. I certify that this annual report complies with: > the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and > the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on page 90 of this Annual Report or accessed at http://www.queenslandtheatre.com.au/About-Us/Publications Yours sincerely Cover photographs, Top – Bottom: 1. Boston Marriage, Amanda Muggleton, Rachel Gordon. Photography by Rob Maccoll. Emeritus Professor Richard Fotheringham FAHA 2. Ladies in Black, Kate Cole, Christen O’Leary, Naomi Price, Lucy Maunder, Deidre Rubenstein. Photography by Rob Maccall. Chair, Queensland Theatre Company 3. Happy Days, Carol Burns. Photography by Aaron Tait. 4. Oedipus Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Ellen Bailey. Photography by Stephen Henry. 5. Rumour Has It, Naomi Price. Photography by Dylan Evans. 6. Grounded, Libby Munro. Photography by Stephen Henry. 7. Argus, Lauren Hayne, Nathan Booth, Matthew Seery, Anna Straker. 8. Oedipus Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Emily Burton, Toby Martin, Ellen Bailey. 9. Brisbane, Lucy Coleby, Dash Kruck. 10. Home, Margi Brown-Ash. Photography by Aaron Tait. 11. The Odd Couple, Jason Klarwein. Photography by Rob Maccoll. 12. The 7 Stages of Grieving, Chenoa Deemal. Photography by Justin Harrison. -

Annual Report 2014 1

Annual Report 2014 1 2 3 4 6 5 7 Cover photographs 1 Paul Bishop in Australia Day 2 Candy Bowers in The Mountaintop 3 Jason Klarwein and Veronica Neave in Macbeth 4 Anna McGahan in The Effect 5 Christen O’Leary in Gloria 6 Promotional photograph for Black Diggers 7 Steven Rooke in Gasp! Photography: Aaron Tait, Branco Gaica (Black Diggers) Illustration: Lauren Marriott (The Mountaintop) Letter to Minister 27 March 2015 The Honourable Annastacia Palaszczuk MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Level 15, Executive Building 100 George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Premier I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2014 and audited financial statements for the Queensland Theatre Company. I certify that this annual report complies with: the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on page 90 of this annual report or accessed at http://www.queenslandtheatre.com.au/About-Us/Publications Yours sincerely, Professor Richard Fotheringham Chair Queensland Theatre Company Queensland Theatre Company Annual Report 1 2 Queensland Theatre Company Annual Report Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... -

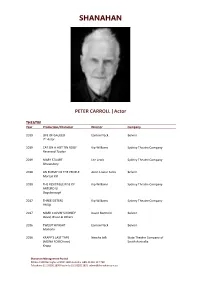

PETER CARROLL |Actor

SHANAHAN PETER CARROLL |Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2019 LIFE OF GALILEO Eamon Flack Belvoir 7th Actor 2019 CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Reverend Tooker 2019 MARY STUART Lee Lewis Sydney Theatre Company Shrewsbury 2018 AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Morton Kiil 2018 THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company ARTURO UI Dogsborough 2017 THREE SISTERS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Phillip 2017 MARK COLVIN’S KIDNEY David Berthold Belvoir David, Bruce & Others 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT Eamon Flack Belvoir Malvolio 2016 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of (MONA FOMO tour) South Australia Krapp Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 SEVENTEEN Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Tom 2015 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of Krapp South Australia 2014 CHRISTMAS CAROL Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Marley and Other 2014 OEDIPUS REX Adena Jacobs Belvoir Oedipus 2014 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTIAN Matthew Lutton Malthouse Theatre Mr Hugo Sword 2012-13 CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG Roger Hodgman TML Enterprises Grandpa Potts 2012 OLD MAN Anthea Williams B Sharp Belvoir (Downstairs) Albert 2011 NO MAN’S LAND Michael Gow QTC/STC Spooner 2011 DOCTOR ZHIVAGO Des McAnuff Gordon Frost Organisation Alexander 2010 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Stuart Maunder Opera Australia Major-General Stanley 2010 KING LEAR Marion Potts Bell -

By Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman with Lisa Flanagan

Sydney Theatre Company Education present By Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman With Lisa Flanagan Directed by Leah Purcell Teacher's Resource Kit Written and compiled by Robyn Edwards and Samantha Kosky sydneytheatre.com.au/education Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Sydney Theatre Company’s The 7 Stages of Grieving Teacher’s Notes © 2008 1 IMPORTANT INFORMATION The 7 Stages of Grieving By Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman Season 22 February – 20 March 2008 Venue Wharf 2, Sydney Theatre Company Pier 4/5 Hickson Road,Walsh Bay Touring The 7 Stages of Grieving will tour to Griffith Regional Arts Centre (2 April), Wagga Wagga Civic Theatre (4, 5, 7 April) and Albury Performing Arts Centre 9, 10 April). This tour has been made possible by Arts NSW through the ConnectED programme. Sydney Theatre Company would like to take this opportunity to warn members of the audience that this production contains names and visual representations of people recently dead, which may be distressing to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. All care has been taken to acquire the appropriate permission and show all proper respect. The performance time is approximately one hour. Please note there will be no interval and latecomers will not be admitted. We respectfully ask teachers discuss theatre etiquette with students prior to attending the performance. We respectfully ask that you discuss theatre etiquette with your students prior to coming to the performance. -

Women in Theatre

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Creative Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2012 Women in theatre Elaine Lally University of Technology, [email protected] Sarah Miller University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/creartspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Lally, Elaine and Miller, Sarah: Women in theatre 2012. https://ro.uow.edu.au/creartspapers/268 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Women in theatre Published by: Australia Council 2012 Copyright: © Australia Council for the Arts This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Australia Council. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Marketing and Audience Development, Australia Council for the Arts, 372 Elizabeth Street, Surry Hills NSW 2010 Australia Email: [email protected] Phone: +61 (0)2 9215 9000 Toll Free 1800 226 912 Fax: +61 (0)2 9215 9074 http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au Women in theatre Assoc Prof Elaine Lally Creative Practices and Cultural Economy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in consultation with Prof Sarah Miller Faculty of Creative Arts University of Wollongong Contents Executive summary 4 Acknowledgements 6 Reviewing progress to date 7 Reviewing progress from the 1980s to the present 9 The 1980s 9 The 1990s 12 The 2000s 14. -

The Blackwords Symposium: the Past, Present, and Future of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Literature

The BlackWords Symposium: The Past, Present, and Future of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Literature KERRY KILNER University of Queensland PETER MINTER University of Sydney We write to create, to survive, and to revolutionise; we write to haunt and we ache because we refuse to leave the past alone. We aim to disrupt the State’s founding order of things, to disrupt ‘patriarchal white sovereignty’ (Moreton- Robinson), white heteronormativity, and the colonial-continuum of history. (Harkin, herein) The BlackWords Symposium, held in October 2012, celebrated the fifth anniversary of the establishment of BlackWords, the AustLit-supported project recording information about, and research into, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers and storytellers. The symposium showcased the exciting state of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander creative writing and storytelling across all forms, contemporary scholarship on Indigenous writing, alongside programs such as the State Library of Queensland’s black&write! project, which supports writers’ fellowships, editing mentorships, and a trainee editor program for professional development for Indigenous editors. But really, the event was a celebration of the sort of thinking, the sort of resistance, and the re-writing of history that is evident in the epigraph to this introduction. The speakers, who included Melissa Lucashenko, Wesley Enoch, Sandra Phillips, Ellen Van Neerven, Jeanine Leane, and Boori Pryor alongside the authors of the works in this collection, explored a diverse range of topics -

1 Australian Indigenous Performing Arts and Cultural Policy Authors

Australian Indigenous performing arts and cultural policy Authors Hilary Glow Bowater School of Management and Marketing Deakin University [email protected] Katya Johanson School of Communication and Creative Arts Deakin University [email protected] Word count: 6700 Keywords: Australian Indigenous theatre, Indigenous cultural policy. Abstract This paper examines how Australian Indigenous cultural policies have contributed to the development of Aboriginal theatre since the early 1990s. In many respects, the flourishing of Indigenous performing arts exemplify the priorities of national cultural policy more broadly. These priorities include the assertion of national identity in a globalised world – a goal that is amply realised in the publicly funded Indigenous performing arts. The paper examines how government policies have assisted the growth of Indigenous theatre companies and the professional development of their artists. It draws on interviews with Indigenous theatre artists to identify their changing professional needs, and argues that cultural policies need to develop pluralist strategies which encourage a diversity of practices for the future development of the sector. Introduction I think all my work has been absolutely defined by the search for an articulation of an Indigenous voice. 1 Wesley Enoch The Indigenous performing arts sector received unprecedented political and financial support from government in the early 1990s. Indigenous arts were and still are regarded as an important means of expressing what is culturally unique about Australia, to assist in advancing the political goal of reconciliation between white and Indigenous Australians, and to address a range of social, economic and cultural problems Indigenous Australians experience. Since the early 1990s, there has been little review of how the Indigenous performing arts companies and their artists have fared with these substantial expectations of their work. -

Black Diggers

Black Diggers A Queensland Theatre Company and Sydney Festival Tue 10 Mar – Sat 14 Mar co-production Her Majesty’s Theatre Photo: Branco Gaica Photo: Written by Tom Wright and BASS 131 246 directed by Wesley Enoch adelaidefestival.com.au PRESENTING PARTNER Black Diggers A Queensland Theatre Company and Sydney Festival co-production Written by Tom Wright and directed by Wesley Enoch WRITER Tom Wright CAST George Bostock, Luke Carroll, Shaka Cook, Trevor Jamieson, Kirk Page, Guy Simon, Colin Smith, Eliah Watego and Tibian Wyles SET DESIGNER Stephen Curtis COSTUME DESIGNER Ruby Langton-Batty COMPOSER/SOUND DESIGNER Tony Brumpton DRAMATURG Louise Gough CULTURAL CONSULTANT George Bostock RESEARCHER David Williams This production has been assisted by the Australian Government’s Major Festival initiative, managed by the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, in association with the Confederation of Australian International Arts Festivals, Adelaide Festival, Brisbane Festival, Perth International Arts Festival and Sydney Festival TOURING PARTNERS Queensland Theatre Company’s tour of Black Diggers is supported by the Australian Government’s Anzac Centenary Arts and Culture Fund and Sibelco Australia DURATION: 1 HOUR 40 MINUTES (NO INTERVAL) Contains low level coarse language and adult references to death and war, as well as use of herbal cigarettes. ACCESS INFORMATION ENJOY THE SHOW? SUPPORT ADELAIDE FESTIVAL DON’T FORGET TO VISIT Share your thoughts Become a Patron of the online now! Adelaide Festival to support /adelaidefestival our innovative and bold artistic vision and access exclusive ELDER PARK AND SURROUNDS, @adelaidefest #AdlFest benefits and events. Find out FREE EVERY NIGHT OF THE adelaidefestival.com.au more at adelaidefestival.com.au FESTIVAL Photo: Branco Gaica Photo: DIRECTOR’S NOTE When constructing this piece of theatre we One purpose of Indigenous theatre is to were confronted by the enormity of the task, write on to the public record neglected or the cultural protocols, the military records, the forgotten stories. -

Sydney Theatre Company Announces Act 1: the First Five Plays of 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sunday 1 November, 2020 Sydney Theatre Company announces Act 1: the first five plays of 2021 Sydney Theatre Company Artistic Director Kip Williams today unveiled Act 1, the first five plays of the 2021 season with the remaining two thirds of the season to be announced in March. To celebrate the company’s return to its newly renovated home at The Wharf, Williams will direct a new adaptation by Kate Mulvany of Ruth Park’s classic Sydney story, Playing Beatie Bow. The 2021 season will also feature the Australian premiere of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ dark comedy, Appropriate directed by Wesley Enoch at Roslyn Packer Theatre and three plays rescheduled from the 2020 season: Home, I’m Darling, Fun Home and The Wharf Revue: Goodnight and Good Luck. Artistic Director Kip Williams said: “To celebrate the exciting new creative possibilities of the theatres at The Wharf, I’m putting together a special collection of plays and I’m thrilled that the first of these is the beloved story Playing Beatie Bow - a favourite book from my own childhood. This will be a show for young and old and we’re hoping that it will introduce a new generation of theatre-lovers to The Wharf. As we come home to The Wharf, I’m so excited to be telling a story set in our local area, The Rocks’. We’re thrilled to welcome Wesley Enoch back to STC for the Australian premiere of Appropriate, a phenomenal piece of writing from one of the most exciting playwrights in America at the moment, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. -

Performing Australia's Black and White History: Acts of Danger in Four

Performing Australia’s black and white history: acts of danger in four Australian plays of the early 21st century. Alison Lyssa B.A. H111 (University of Sydney), Dip. Ed. (Sydney Teachers College) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the Degree of Masters in English in the Division of Humanities Macquarie University 6 June 2006 Alison Lyssa’s former surname through marriage was Hughes. Her birth surname was Darby. 2 3 Table of Contents Summary.....................................................................................................................5 Candidate’s statement ................................................................................................7 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................8 Introduction ...............................................................................................................11 Selection of plays for analysis ...............................................................................11 A note on the Conversations with the Dead texts ..............................................16 Political and cultural context ..................................................................................17 The genesis of the plays........................................................................................23 Productions and venues ........................................................................................27 Performance as testimony.....................................................................................33