1 Setp Foundation Oral History Program Oh-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Resolution (1072KB)

International Aerobatic Club CHAPTER 38 January 2010 Newsletter PREZ POST Happy New Years! First of all, I would like to welcome everyone to 2010. It seems like each year goes by faster and faster. 2009 was a very difficult year for the economy, aerobatic community, Quisque .03 and air show industry. Like many of you, I’m looking forward to a much brighter year. The economy seems to be turning around, aircraft are starting to trade hands, and camps are starting to get scheduled. Unlike the rest of the country, the Bay Area weather has been rather calm, Cory Lovell allowing many of us the opportunity to get in a few practice President, Ch 38 sessions. I’ve also talked to several members who are taking the winter months to change out radios, upgrade engines, and fix the little things kept getting pushed out because of a contest. Integer .05 Continued on Page 2………. Issue [#]: [Issue Date] Continued from Page 1……. As you may have noticed, this is the first newsletter in a couple of months. With the unfortunate loss of Che Barnes and the retirement of Peter Jensen, we did not have anyone come forward to help with the Newsletter (we’re still looking for a couple volunteers). 2009 was also a crazy year for me, hence the fact I haven’t been able to get out a newsletter. I left my job in September to travel to Spain, then over to Germany of Oktoberfest. I also took some time to put together a website for Sukhoi Aerobatics and spend some time doing formation aerobatics training with Bill Stein and Russ Piggott. -

Memorandum Board of Supervisors

MEMORANDUM OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS COUNTY OF PLACER TO: Honorable Board of Supervisors FROM: Jennifer Montgomery Supervisor, District 5 DATE: October 9,2012 SUBJECT: RESOLUTION - Adopt and present a Resolution to Clarence Emil "Bud" Anderson for his outstanding service to his country and his community. ACTION REQUESTED Adopt and present a Resolution to Clarence Emil "Bud" Anderson for his outstanding service to his country and his community. BACKGROUND Colonel Anderson has over thirty years of military service, and was a test pilot at Wright Field where he also served as Chief of Fighter Operations. He also served at Edwards Air Force Base where he was Chief of Flight Test Operations and Deputy Director of Flight Test. Colonel Anderson served two tours at The Pentagon and commanded three fighter organizations. From June to December 1970, he commanded the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, an F-105 Thunderchief unit, during its final months of service in the Vietnam War, and retired in March 1972. He was decorated twenty-five times for his service to the United States. After his retirement from active duty as a Colonel, he became the manager of the McDonnell Aircraft Company's Flight Test Facility at Edwards AFB, serving there until 1998. During his career, he flew over 100 types of aircraft, and logged over 7,000 hours. Anderson is possibly best known for his close friendship with General Chuck Yeager from World War II, where both served in the 35th Fighter Group, to the present. Yeager once called him "The best fighter pilot I ever saw". -

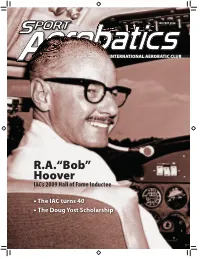

“Bob” Hoover IAC’S 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee

JANUARY 2010 OFFICIALOFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF TTHEHE INTERNATIONALI AEROBATIC CLUB R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee • The IAC turns 40 • The Doug Yost Scholarship PLATINUM SPONSORS Northwest Insurance Group/Berkley Aviation Sherman Chamber of Commerce GOLD SPONSORS Aviat Aircraft Inc. The IAC wishes to thank Denison Chamber of Commerce MT Propeller GmbH the individual and MX Aircraft corporate sponsors Southeast Aero Services/Extra Aircraft of the SILVER SPONSORS David and Martha Martin 2009 National Aerobatic Jim Kimball Enterprises Norm DeWitt Championships. Rhodes Real Estate Vaughn Electric BRONZE SPONSORS ASL Camguard Bill Marcellus Digital Solutions IAC Chapter 3 IAC Chapter 19 IAC Chapter 52 Lake Texoma Jet Center Lee Olmstead Andy Olmstead Joe Rushing Mike Plyler Texoma Living! Magazine Laurie Zaleski JANUARY 2010 • VOLUME 39 • NUMBER 1 • IAC SPORT AEROBATICS CONTENTS FEATURES 6 R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee – Reggie Paulk 14 Training Notes Doug Yost Scholarship – Lise Lemeland 18 40 Years Ago . The IAC comes to life – Phil Norton COLUMNS 6 3 President’s Page – Doug Bartlett 28 Just for Starters – Greg Koontz 32 Safety Corner – Stan Burks DEPARTMENTS 14 2 Letter from the Editor 4 Newsbriefs 30 IAC Merchandise 31 Fly Mart & Classifieds THE COVER IAC Hall of Famer R. A. “Bob” Hoover at the controls of his Shrike Commander. 18 – Photo: EAA Photo Archives LETTER from the EDITOR OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Publisher: Doug Bartlett by Reggie Paulk IAC Manager: Trish Deimer Editor: Reggie Paulk Senior Art Director: Phil Norton Interim Dir. of Publications: Mary Jones Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh Contributing Authors: Doug Bartlett Lise Lemeland Stan Burks Phil Norton Greg Koontz Reggie Paulk IAC Correspondence International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

“One of the World's Best Air Shows” Coming to Goldsboro, NC Seymour

For Immediate Release “One of the world’s best air shows” coming to Goldsboro, NC USAF Thunderbirds – Courtesy Staff Sgt Richard Rose Jr. Seymour Johnson AFB – Goldsboro, NC – “Wings Over Wayne is one of the world’s best air shows,” said Chuck Allen, Mayor of Goldsboro. “Seymour Johnson does a phenomenal job attracting the best lineup of airpower and performers, alongside the F-15E Strike Eagle and KC-135 aircraft already stationed at the base.” Located in Goldsboro, the seat of Wayne County, Seymour Johnson Air Force Base will stage and choreograph the Wings Over Wayne Air Show on Saturday and Sunday, April 27-28. Headlining the exhibition from Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, is the premier Air Force jet demonstration team, the Thunderbirds. The gates open each day at 9 AM, with aerial displays from 11 AM until 4:30 PM. “As our guests, you will be able to see world-class acrobatics and ground demonstrations that are truly a sight to be seen,” said Colonel Donn Yates, Commander of Seymour Johnson’s 4thFighter Wing. “Some of the performers scheduled include the F- 35 Demonstration Team, Tora! Tora! Tora!, the US Army Black Daggers, the B-2 Spirit, and other elite aircraft within the Air Force Arsenal.” Wings Over Wayne is a family-friendly expo including the Kids’ Zone, occupying one of the largest aircraft hangars on the base. A $10 admission charge covers access to the Zone for the entire day. “There is something for everyone,” said Colonel Yates. “Come out and witness this spectacular show while enjoying great food and fun with your family and ours.” “For the more serious air show enthusiasts, the two-day show has evolved into an air show week,” said Mayor Allen. -

Team Oracle 2018 Media Kit

TEAM ORACLE 2018 MEDIA KIT SOARING ON IN THE ORACLE CHALLENGER III For media flights, interviews, photos & video: Suzanne Herrick, Fedoruk & Associates, Inc., 612-247-3079 [email protected] PHOTO BY Mike Killian Follow Sean D. Tucker at: facebook.com/SeanDTucker instagram.com/TeamOracle twitter.com/SeanDTucker & twitter.com/TeamOracle The Team Oracle Airplane Channel on YouTube FASTEN YOUR SEAT BELTS AND HOLD ON TIGHT. IT’S TIME FOR SOME HEART-CHARGING, HIGH-PERFORMANCE POWER AEROBATICS FROM THE LEGEND HIMSELF, MR. SEAN D. TUCKER. THE 2018 TEAM ORACLE AIR SHOW SEASON IS UNDERWAY, FILLED WITH AWE-INSPIRING MOMENTS, THRILLS AND ADRENALINE. This season marks Tucker’s last as a solo performer with exciting plans in store for a performance team. If you haven’t had the opportunity to interview Tucker or better yet, experience flight with Team Oracle, this is the year. Contact Suzanne Herrick at 612-247-3079 or [email protected] for times and options. PHOTO BY Peter Tsai SOARING WITH THE DREAM MACHINE • More than half of Tucker’s power aerobatic maneuvers are unique making Tucker’s performance an unforgettable, awe-inspiring experience. • During the 13-minute Sky Dance performance, Tucker will pull more than nine positive g-forces and more than seven negative g-forces. • The Sky Dance begins with a breathtaking three-quarter loop with eight to 10 snap rolls in which Tucker reaches speeds up to 280 miles per hour at more than 400 degrees per second and six positive g-forces. • Tucker is the world’s only pilot to perform the Triple Ribbon Cut in which he flies just 20 feet above the ground, cutting ribbons on poles placed a mere 750 feet apart. -

Discovering the Opportunities

Discovering the Opportunities LABOR, LIFESTYLE, LOS ANGELES ALL WITHIN REACH! 2008 ECONOMIC ROUNDTABLE REPORT Table of Contents Introduction ■ THE GREATER ANTELOPE VALLEY The Greater Antelope Valley Area Profile 1 The Antelope Valley is an extensive economic region encompassing some 3,000 Map 1 square miles that includes portions of two (2) counties and five (5) incorporated cities. Now home to some 460,000 residents, the Antelope Valley is rapidly ■ DEMOGRAPHICS evolving into a stronger and more influential economic region. Its size is larger Population Detail 2 than the state of Connecticut and is diverse in resources, topography and climate. Comparisons 3 The Antelope Valley continues its heritage as one of the premier aerospace flight Antelope Valley Cities 4-9 test and research resources in the nation, while maintaining agricultural roots as Rural Areas 9 the largest agricultural producer in Los Angeles County of a number of crops. The ■ ECONOMY retail market continues to develop and is rapidly becoming home to a number Major Employers/Industries 10 of the nation’s leading retailers. The region’s industrial market is coming of age, Workforce 10 offering hundreds of thousands of square feet of brand new state-of-the-art facilities Average Salary by Industry Sector 11 for lease or purchase. Inventory of available land is plentiful and affordable, with a Cost of Doing Business 12 location close to the amenities offered in the Los Angeles Basin. Transportation 13 The Antelope Valley provides a fertile environment for economic growth and offers Enterprise Zone 14 a wide range of benefits to businesses seeking to re-locate or expand into the area. -

Model Builder September 1975

, Μ π η π SEPTEMBER 197Γ» ohniti b, luimfioi 4! MORROW RieHé prodnrtl! lie Here we to sell §enice lods«}· DECEMBER 1985 ' i i · i I I •••"HUM Since we started in 1962, over 50 radio control manufacturers have come and gone. Long term, radio control equipment is no better than the service backing it. Whether you own our first 1964 KP-4 or our latest Signature Series, you can be sure of service continuity. This is another important reason for selecting Kraft. WRITE FOR FREE CATALOG Worlds Largest Manufacturer of Proportional R/C Equipment 450 WEST CALIFORNIA AVENUE, P.O. BOX 1268, VISTA, CALIFORNIA 92083 \ A .23 POWERED PATTERN SHIP FOR SPORT AND COMPETITION FIRST CAME THE PACER--it started a whole new revolutionary category of model planes, the 1/2A pattern ship. Then people wanted a larger, fully competitive version with the same features--good looks, easy construction, sensible design, light weight, fuel economy, and solid performance at an affordable price. Here it is, the Super Pacer. For the economically minded pattern ship flier. All balsa and ply construction. Quick to build, light and sturdy to last long. It has to be a sin to get so much enjoyment out of the performance obtained at so little expense. Try your dealer first. You can order direct if he doesn't have it. [ ] Send me a Super Pacer. Enclosed is $32.95 plus $1.00 handling. ] Send me your complete catalog. Enclosed is $1.00 (add $.50 for 1st Class mail return.) MB ( A tII P /C .lIn c .) BOX 511, HIGGINSVILLE, MO. -

PRESS RELEASE – Chuck Yeager

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE YEAGER AIRPORT MOURNS PASSING OF GENERAL CHUCK YEAGER Yeager Airport Staff and the Central West Virginia Regional Airport Board Members are mourning the loss of Brig. Gen. Charles “Chuck” Yeager today. His bravery and dedication will be remembered around the world for generations to come. “Gen. Yeager is a true pioneer in the world of aviation,” said Yeager Airport Director and CEO NicK Keller. “It is rare to be the first to ever do something, and Gen. Yeager did that by breaking the sound barrier and putting our great country ahead of its time in aviation.” General Yeager got his start as a pilot in 1941 when he signed for the Army Air Corps, now Known as the U.S. Air Force. Yeager’s military career spanned six decades and four wars. During World War II, Gen. Yeager flew 64 missions and shot down 13 German planes. Yeager’s plane was shot down over France in 1944 but he escaped capture. After the war, in true West Virginia fashion, Yeager continued serving his country as a flight instructor and test pilot at Wright Field in Ohio. It was there that his exceptional sKills were quicKly recognized, and he was chosen to be the first to fly the rocKet-powered Bell X-1. “General Yeager exemplified everything it means to be a West Virginian”, said Central West Virginia Regional Airport Authority Board Chairman Ed Hill. “Born and raised in Lincoln County, General Yeager’s hard work, dedication, skill, and bravery defined his historic career. Our entire Board is saddened by the loss of a fellow West Virginian, and a leader in aviation.” Yeager made history in 1947, when his Bell X-1 broke the speed of sound over a lake in Southern California. -

Brigadier General Chuck Yeager Collection, 1923-1987

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2010 0455: Brigadier General Chuck Yeager Collection, 1923-1987 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons GENERAL CHARLES E. "CHUCK" YEAGER PAPERS Accession Number: 1987/0455 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2010 • GENERAL CHARLES E. "CHUCK" YEAGER PAPERS Accession Number: 455 Processed by: Kathleen Bledsoe, Nat DeBruin, Lisle Brown, Richard Pitaniello Date Finally Completed: September 2010 Location: Special Collections Department Chuck Yeager and Glennis Yeager donated the collection in 1987. Collection is closed to the public until the death of Charles and Glennis Yeager . • -2- TABLE OF CONTENTS Brigadier General Chuck E. "Chuck" Yeager ................................................................................ 4 The Inventory - Boxed Files ....................................................................................................... 9 The Inventory - Flat Files ......................................................................................................... 62 The Inventory - Display Cases in the General Chuck Yeager Room ....................................... 67 Accession 0234: Scrapbook and Clippings compiled by Susie Mae (Sizemore) Yeager..................75 -

X-15 Manuscript

“X-15: WINGS INTO SPACE, Flying the First Reusable Spacecraft” by Michelle Evans University of Nebraska Press, Outward Odyssey series © 2012 In the Footsteps of the X-15 The primary place associated with the X-15 is Edwards AFB, California. However, there are many other locations where you can directly see the areas the rocket planes flew and landed, where men tracked them through the upper atmosphere and beyond, to find the surviving aircraft today, and where you may pay your respects to some of the men who made the world’s first reusable spacecraft possible. This appendix provides information on disposition of the various aircraft, engines, and mockups, as well as a tour itinerary for those interested in following the footsteps of the X-15. Beside making an excellent historic multi-day field trip for a group from scout - ing or as a school project, this tour is perfect for anyone with a bit of adventure and ex - ploration in their soul. The full tour can comfortably take a week or more, depending on how much time is spent at various locations and taking in the surrounding areas. Some sections, such as Palmdale/Lancaster to Cuddeback Dry Lake, then on to the Mike Adams memorial, may be accomplished in a single day for short excursions. 1. DISPOSITION OF ARTIFACTS Three X-15s were built by North American Aviation. The plant was at the southeast cor - ner of Los Angeles International Airport, which is now the location of the airport’s cargo terminal, near the intersection of Imperial Highway and Aviation Boulevard. -

Flight Line the Official Publication of the CAF Southern California Wing 455 Aviation Drive, Camarillo, CA 93010 (805) 482-0064

Flight Line The Official Publication of the CAF Southern California Wing 455 Aviation Drive, Camarillo, CA 93010 (805) 482-0064 June, 2015 Vol. XXXIV No. 6 © Photo by Frank Mormillo See Page 19 for story of air terminal named for Capt. David McCampbell – Navy pilot of Minsi III Visit us online at www.cafsocal.com © Photo Courtesy of Dan Newcomb Here’s Col. Dan Newcomb in one of his favorite seats – the rear seat in Marc Russell’s T-34. Dan wears several hats in our Wing. Other than his helmet, he is a long-time member of the PBJ Restoration Team; is the official historian of our PBJ-1J “Semper Fi;” is a “Flight Line” author and photographer; and currently has taken on the job of Cadet Program Manager. See his stories on pages 12 and 17. Thanks for all you do, Dan! Wing Staff Meeting, Saturday, June 20, 2015 at 9:30 a.m. at the CAF Museum Hangar, 455 Aviation Drive, Camarillo Airport THE CAF IS A PATRIOTIC ORGANIZATION DEDICATED TO THE PRESERVATION OF THE WORLD’S GREATEST COMBAT AIRCRAFT. June 2015 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 Museum Closed Work Day Work Day Work Day 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Museum Closed Work Day Work Day Work Day 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Museum Closed Work Day Work Day Docent Wing Staff Meeting 3:30 Meeting 9:30 Work Day 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Longest Day Museum Closed Work Day Work Day Work Day of the Year 28 29 30 Museum Open Museum Closed Work Day 10am to 4pm Every Day Memorial Day Except Monday and major holidays STAFF AND APPOINTED POSITIONS IN THIS ISSUE Wing Leader * Ron Missildine (805) 404-1837 [email protected] Wing Calendar . -

Devon Strut News, December 2006

REPRESENTING SPORT & RECREATIONAL AVIATION IN THE SOUTHWEST www.devonstrut.co.uk DEVON STRUT NEWS, DECEMBER 2006. CO-ORDINATOR’S COMMENTS by Christopher Howell Liability insurance has reared its ugly head during this month of November. The South Hams Flying Club based at Halwell has to make the difficult decision whether to close the airfield to all visiting aircraft and cancel their 2007 fly-in. Why? Because, like at many of our local strips, a visit for a cup of tea and a natter have all been at the pilots own risk. Now, if some clever insurance company spots an opening for shifting the blame on to the landowner, hey-ho, where’s your policy Mr Farmer!! A quick call to PFA HQ elicited “Oh, I am surprised that strip owners have not got liability insurance, foolish beings!” So there lies a story. When I called around to our entire 14 fly-in venues this year I met with very mixed responses. Some strip owners are operating on restricted incomes and the added burden of several hundred pounds going to the very slight opening that some clever clogs may find will not warrant the added expense. Some strip owners do not have that many visitors but enjoy holding a fly-in once a year. Other owners do not welcome any visitors except for those at their once a year social chin-wag and fly-in. Now we are tasked with finding a satisfactory solution, otherwise flying to friends’ strips on a sunny afternoon will be terminated! I have contacted the PFA and asked for Primary Liability cover for fly-ins.