RESEARCHING the LEOMINSTER CANAL Paper 2 : SURVEYS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Symposium Edition the Ground Beneath Our Feet: 200 Years of Geology in the Marches

NEWSLETTER August 2007 Special Symposium Edition The ground beneath our feet: 200 years of geology in the Marches A Symposium to be held on Thursday 13th September 2007 at Ludlow Assembly Rooms Hosted by the Shropshire Geological Society in association with the West Midlands Regional Group of the Geological Society of London To celebrate a number of anniversaries of significance to the geology of the Marches: the 200th anniversary of the Geological Society of London the 175th anniversary of Murchison's epic visit to the area that led to publication of The Silurian System. the 150th anniversary of the Geologists' Association The Norton Gallery in Ludlow Museum, Castle Square, includes a display of material relating to Murchison's visits to the area in the 1830s. Other Shropshire Geological Society news on pages 22-24 1 Contents Some Words of Welcome . 3 Symposium Programme . 4 Abstracts and Biographical Details Welcome Address: Prof Michael Rosenbaum . .6 Marches Geology for All: Dr Peter Toghill . .7 Local character shaped by landscapes: Dr David Lloyd MBE . .9 From the Ground, Up: Andrew Jenkinson . .10 Palaeogeography of the Lower Palaeozoic: Dr Robin Cocks OBE . .10 The Silurian “Herefordshire Konservat-Largerstatte”: Prof David Siveter . .11 Geology in the Community:Harriett Baldwin and Philip Dunne MP . .13 Geological pioneers in the Marches: Prof Hugh Torrens . .14 Challenges for the geoscientist: Prof Rod Stevens . .15 Reflection on the life of Dr Peter Cross . .15 The Ice Age legacy in North Shropshire: David Pannett . .16 The Ice Age in the Marches: Herefordshire: Dr Andrew Richards . .17 Future avenues of research in the Welsh Borderland: Prof John Dewey FRS . -

Worcestershire Roads and Roadworks Report

Worcestershire Roads and Roadworks Report 27/05/2019 to 09/06/2019 Works impact : High Lower Public Event impact : High Lower Traffic Traffic Light Road No. Expected Expected District Location Street Name Town / Locality Works Promoter Work / Event Description Management Manual Control (A & B Only) Start Finish Type Requirements Water mains replacement work to be carried out in conjunction with the work on Money Bromsgrove Jcn of B4551 Money Lane to the jcn of A491 Sandy Lane Malthouse Lane Chadwich Severn Trent Water 18/03/2019 04/07/2019 Road Closure Lane, road is not wide enough to maintain traffic flow safely. The Junction Of B4091 Stourbridge Road To The Junction Of Worcestershire Bromsgrove Broad Street Bromsgrove 27/05/2019 02/06/2019 Carriageway Resurfacing (5 days in period) Road Closure U21233 Crabtree Lane Highways The Junction Of C2058 Whettybridge Road To For A Distance Bromsgrove Of Approx. 440.00 Meters In A South Westerly Direction Along Holywell Lane Rubery Severn Trent Water 28/05/2019 30/05/2019 To Install A New Boundary Box And Meter Road Closure U21425 Holywell Lane The Junction Of U21055 South Road To The Junction Of Bromsgrove Stoke Road Bromsgrove Severn Trent Water 02/06/2019 02/06/2019 Short Comm Pipe Install 25mm Road Closure B4184 New Road Jcn of U21543 Golden cross lane to the jcn of A38 Halesowen Worcestershire Bromsgrove Woodrow Lane Catshill 03/06/2019 12/06/2019 Surface dressing (1 day in period) Road Closure Road Highways The Junction Of A38 Lydiate Ash Roundabout & The Junction Of U21519 Cavendish Close To The Junction Of Worcestershire Bromsgrove A38 Lickey End Roundabout A38 Birmingham Road Marlbrook 03/06/2019 14/06/2019 Carriageway Resurfacing (3 nights in period) Road Closure Highways & The Junction Of U20062 Marlbrook Gardens (Night Closures 20:00 - 06:00) The Junction Of B4120 Kendal End Road To Approx. -

Ludlow Bus Guide Contents

Buses Shropshire Ludlow Area Bus Guide Including: Ludlow, Bitterley, Brimfield and Woofferton. As of 23rd February 2015 RECENT CHANGES: 722 - Timetable revised to serve Tollgate Road Buses Shropshire Page !1 Ludlow Bus Guide Contents 2L/2S Ludlow - Clee Hill - Cleobury Mortimer - Bewdley - Kidderminster Rotala Diamond Page 3 141 Ludlow - Middleton - Wheathill - Ditton Priors - Bridgnorth R&B Travel Page 4 143 Ludlow - Bitterley - Wheathill - Stottesdon R&B Travel Page 4 155 Ludlow - Diddlebury - Culmington - Cardington Caradoc Coaches Page 5 435 Ludlow - Wistanstow - The Strettons - Dorrington - Shrewsbury Minsterley Motors Pages 6/7 488 Woofferton - Brimfield - Middleton - Leominster Yeomans Lugg Valley Travel Page 8 490 Ludlow - Orleton - Leominster Yeomans Lugg Valley Travel Page 8 701 Ludlow - Sandpits Area Minsterley Motors Page 9 711 Ludlow - Ticklerton - Soudley Boultons Of Shropshire Page 10 715 Ludlow - Great Sutton - Bouldon Caradoc Coaches Page 10 716 Ludlow - Bouldon - Great Sutton Caradoc Coaches Page 10 722 Ludlow - Rocksgreen - Park & Ride - Steventon - Ludlow Minsterley Motors Page 11 723/724 Ludlow - Caynham - Farden - Clee Hill - Coreley R&B Travel/Craven Arms Coaches Page 12 731 Ludlow - Ashford Carbonell - Brimfield - Tenbury Yarranton Brothers Page 13 738/740 Ludlow - Leintwardine - Bucknell - Knighton Arriva Shrewsbury Buses Page 14 745 Ludlow - Craven Arms - Bishops Castle - Pontesbury Minsterley Motors/M&J Travel Page 15 791 Middleton - Snitton - Farden - Bitterley R&B Travel Page 16 X11 Llandridnod - Builth Wells - Knighton - Ludlow Roy Browns Page 17 Ludlow Network Map Page 18 Buses Shropshire Page !2 Ludlow Bus Guide 2L/2S Ludlow - Kidderminster via Cleobury and Bewdley Timetable commences 15th December 2014 :: Rotala Diamond Bus :: Monday to Saturday (excluding bank holidays) Service No: 2S 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L Notes: Sch SHS Ludlow, Compasses Inn . -

Development Management Report

Committee and date Item South Planning Committee 7 3 December 2013 Public Development Management Report Responsible Officer: Tim Rogers email: [email protected] Tel: 01743 258773 Fax: 01743 252619 Summary of Application Application Number: 13/04014/MAW Parish : Woofferton Proposal : 500kW Anaerobic Digester (AD) Plant and Associated Infrastructure on Land off Park Lane, Woofferton Site Address : Land off Park Lane, Woofferton Applicant : Ludlow Bioenergy Ltd Case Officer : Graham French email : [email protected] Recommendation:- Grant Permission subject to the conditions and legal obligation set out in Appendix 1. Contact: Tim Rogers (01743) 258773 Page 1 of 40 Land off Park Lane, South Planning Committee – 3 December 2013 Woofferton Statement of Compliance with Article 31 of the Town and Country Development Management Procedure Order 2012 The authority worked with the applicant in a positive and pro-active manner in order to seek solutions to problems arising in the processing of the planning application. This is in accordance with the advice of the Governments Chief Planning Officer to work with applicants in the context of the NPPF towards positive outcomes. The applicant sought and was provided with formal pre-application advice by the authority. Further information has since been submitted on noise, odour and vehicle movements in response to comments received during the planning consultation process. The submitted scheme, has allowed the identified planning issues raised by the proposals to be satisfactorily addressed, subject to the recommended planning conditions and legal agreement. REPORT 1.0 THE PROPOSAL 1.1 The applicant, Ludlow Bioenergy Ltd is proposing to establish an agricultural anaerobic digestion facility at the site which would use feedstock from a nearby poultry unit and from surrounding farmland. -

8.9 MHDC Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 07/09/2020 to 11/09/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 19/00957/FUL Location: Stone Farm, Broadwas, Malvern, WR6 5NE Proposal: Conversion and extension of existing agricultural barn to form a dwelling. Decision Date: 07/09/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr & Mrs Lee & Samantha Ireson Agent: Nick Joyce Architects LTD. Stone Farm 5 Barbourne Road A44 Broadwas Worcester Broadwas WR1 1RS WR6 5NE Parish: Broadwas CP Ward: Broadheath Ward Case Officer: Anna Priestley Expiry Date: 30/08/2019 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862438 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/01086/HP Location: 6 Lower Chase Road, Malvern, WR14 2BX Proposal: Single storey rear kitchen extension. Decision Date: 08/09/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Ms Frances Pearce Agent: Glazzard Architects 6, Lower Chase Road Graingers Porcelain Works Unit 9, S Malvern St Martins Quarter WR14 2BX Silver Street worcester wr12da Parish: Malvern CP Ward: Chase Ward Case Officer: Laura Saich Expiry Date: 02/10/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862422 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 12 Application No: 20/00251/OUT Location: Homestead, Halfkey Road, Malvern, WR14 1UL Proposal: Outline application for the erection of 4no. dwellings with access from Halfkey Road. All other matters reserved. Decision Date: 08/09/2020 Decision: Refusal Applicant: Mr G -

The Story of a Worcestershire Harris Family – Part 2: the Siblings

Foreword Through marriage, the male line of descent of our Harris family has Our work on Part Two of our story has brought an added bonus. By links with Clark, Matthews, Price, Jones and Graves families. delving more deeply into the lateral branches of our tree, our findings have thrown new light on the family of our first known ancestor, John Through the siblings of the Harris males and the families of their Harris, who married Mary Clark in Eastham on 30 December 1779. spouses, we are also linked to such diverse family names as Apperley, Baldwin, Birkin, Boulton, Bray, Browning, Butler, Craik, Brian Harris, Cowbridge, February 2012 Davies, Davis, Garbett, Godfrey, Gore, Gould, Griffiths, Hall, Harrod, Hehir, Homer, Hughes, Moon, Passey, Pitt, Postans, Pound, Preece, Prime, Robotham, Sewell, Skyrme, Sprittles, Stinissen, Thomas,Thurston, Tingle, Turner, Twinberrow, Ward, Yarnold and many more. They are part of a network of Harris connections which takes us beyond the boundaries of Worcestershire, Herefordshire and the rest of the British Isles to Belgium, Australia, Canada and the USA. It may come as a surprise that two of the siblings of Edward James Harris who emigrated to Canada before WWI had already married and started a family in England before leaving these shores. They were George and Edith. Even more surprisingly, Agnes and Hubert, who arrived in Canada as singletons, chose partners who were – like themselves – recently arrived ex-pats and married siblings from the same family of Scottish emigrants, the Craiks. Cover photographs (clockwise from top): There are more surprises in store, including clandestine christenings in a remote Knights Templar church, the mysterious disappearance of 1. -

Worcestershire Roads and Roadworks Report

Worcestershire Roads and Roadworks Report 26/08/2019 - 08/09/2019 Works impact : High Lower Event impact : High Lower Traffic Traffic Light Road No. Expected Expected District Location Street Name Town / Locality Works Promoter Work / Event Description Management Manual Control TMA Ref (A & B Only) Start Finish Type Requirements The Junction With Rowney Green Lane (C2034) To The Worcestershire JZ101214593 Bromsgrove Radford Road Alvechurch 26/08/2019 06/09/2019 Carriageway Patching Road Closure Junction With Watery Lane (C2042) Highways JZ101214602 The Junction Of U22011 Fish House Lane To A Distance Of Worcestershire Bromsgrove Approx 210.84 Meters In A South Easterly Direction Along Sugarbrook Lane Stoke Pound 26/08/2019 30/08/2019 Drainage Work / Flood Alleviation Road Closure JZ101214046 Highways U22012 Sugarbrook Lane From The Junction Of C2062 Dordale Road To Approx 874.00 BC005CC8W00DIGWAKV Bromsgrove Meters In A Northerly Direction Along U20216 Hockley Brook Woodcote Lane Dodford BT Openreach 27/08/2019 29/08/2019 New Customer Connection Road Closure FE1WA1 Lane The Junction Of Alcester Road (A435) To The Junction Of Worcestershire Bromsgrove Billesley Lane Portway 27/08/2019 06/09/2019 Carriageway Patching Road Closure JZ101214625 Lilley Green Road (C2044) Highways The Junction Of C2058 Whettybridge Road To Approx 405.00 Western Power Bromsgrove Meters In A South Westerly Direction Along U21425 Holywell Holywell Lane Rubery 28/08/2019 28/08/2019 Overhead Works Road Closure DY715M41152127881 Distribution Lane Junction With U20216 -

FINAL MAP FRONT.Indd 1 13/02/2014 10:43:14

Coniston Bowness-on- Morton-on-Swale Windermere Coniston Water Kendal Lake R Windermere I V N E E Maunby R V Kirkby E Sedgwick Misperton A C L B C D E F R Newby Bridge G H R Thirsk COSTA A VE Crooklands K RI L BECK E A N COD A Yedingham Ryton C BECK R Topcliffe IV R E Ulverston 14m 8L R R R E IV Dalton YE T E S R S ULVERSTON A 8 W C A Malton CANAL Tewitfield Ripon LE N R I T Norton A P 1 N O L E N Helperby W C 17m 6L R Carnforth 6h Navigation works E D unfinished Bolton-le-Sands Myton-on-Swale R Kirkham Sheriff E 12m 0L 4h Boroughbridge V Hutton I R R IV Howsham E S Navigable waterway: broad, narrow R Linton S 11½m 8L U O R F DRIF Waterway under restoration Lancaster E Strensall FIEL 11m 0L 2½h R D Driffield NA 2 2 E V’N Derelict waterway 5m 0L V 1½h I Earswick 5m 4L Restored as Gargrave Skelton R Brigham Unimproved river historically used for navigation, or drain R single lock 2 4 IV Right of Glasson E navigation Stamford Bridge W Proposed new waterway Galgate L R e 6 E O disputed st B North L Bank Newton ED U eck Frodingham 6 A Skipton S S 10½m 1L Navigable lock; site of derelict lock (where known) E N & 3h 16m 15L 2 11m 2L 3h C L 8h IV Fulford Navigable tunnel; site of derelict tunnel A ER Aik S Greenberfield e 8m 0L Silsden P Beck Thrupp Flight of locks; inclined plane or boat lift; fixed sluice or weir T York POCKLINGTON 3 O Lockington 2½h E OL 10m 1L 3h Sutton CANAL R Pocklington Barnoldswick CA Leven Miles, locks and cruising hours between markers Garstang N C Arram 7m 8L A Tadcaster Navigation Naburn 3 LEVEN C On rivers: 4mph, -

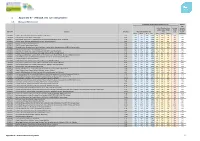

Appendix 2 Commitments

Appendix 2 Commitments Parish Site Number Location Proposal Application Number Number Type not Under Started Construction Abberley CP MIG/14/01122/HOU Land to the west of Apostles Oak Outline application with all matters reserved OUT 25 0 Cottage, The Common, Abberley for a proposed residential development of up to 25 dwellings. MIG/16/00970/HOU Land Adj Sawrey Stockton Road Erection of 1 new detached 4 bedroom house FUL 1 0 Abberley, Worcestershire WR6 and garage. 6AY MHDC/15/HOU Land at Walshes Farm, Clows Outline application for a residential OUT 26 0 Top Road, Abberley, development of up to 26 dwellings with all Worcestershire matters reserved except for access. Alfrick CP MIG/14/00894/HOU Clay Green Farm, Folly Road, Outline application with all matters reserved OUT 23 0 Alfrick, Worcester, WR6 5HN (except for acess) for a residential development comprising 23 dwellings including 9 affordable dwellings. Astley and MIG/16/00107/HOU The Applestore, Red House Lane, Notification for Prior Approval for a Proposed GPDQ 0 3 Dunley CP Dunley, Worcestershire, DY13 Change of Use of Agricultural Building to 0TZ three Dwellinghouses (Class C3), and for Associated Operational Development. MIG/17/01451/HOU Land At (Os 8006 6934), Astley Demolition of existing domestic outbuildings OUT 1 0 Cross and construction of single residential dwelling (all matters reserved except for access). Bayton CP MIG/13/01501/HOU Glebe House, Bayton, Conversion of former coach house into a FUL 0 1 Kidderminster, DY14 9LS dwelling. MHDC/30/HOU Norgroves End Farm, Bayton, Change of Use of Traditional Stone, Timber FUL 1 0 Kidderminster, DY14 9LX and Brick Farm Building to Residential Dwelling. -

Welsh Route Study March 2016 Contents March 2016 Network Rail – Welsh Route Study 02

Long Term Planning Process Welsh Route Study March 2016 Contents March 2016 Network Rail – Welsh Route Study 02 Foreword 03 Executive summary 04 Chapter 1 – Strategic Planning Process 06 Chapter 2 – The starting point for the Welsh Route Study 10 Chapter 3 - Consultation responses 17 Chapter 4 – Future demand for rail services - capacity and connectivity 22 Chapter 5 – Conditional Outputs - future capacity and connectivity 29 Chapter 6 – Choices for funders to 2024 49 Chapter 7 – Longer term strategy to 2043 69 Appendix A – Appraisal Results 109 Appendix B – Mapping of choices for funders to Conditional Outputs 124 Appendix C – Stakeholder aspirations 127 Appendix D – Rolling Stock characteristics 140 Appendix E – Interoperability requirements 141 Glossary 145 Foreword March 2016 Network Rail – Welsh Route Study 03 We are delighted to present this Route Study which sets out the The opportunity for the Digital Railway to address capacity strategic vision for the railway in Wales between 2019 and 2043. constraints and to improve customer experience is central to the planning approach we have adopted. It is an evidence based study that considers demand entirely within the Wales Route and also between Wales and other parts of Great This Route Study has been developed collaboratively with the Britain. railway industry, with funders and with stakeholders. We would like to thank all those involved in the exercise, which has been extensive, The railway in Wales has seen a decade of unprecedented growth, and which reflects the high level of interest in the railway in Wales. with almost 50 per cent more passenger journeys made to, from We are also grateful to the people and the organisations who took and within Wales since 2006, and our forecasts suggest that the time to respond to the Draft for Consultation published in passenger growth levels will continue to be strong during the next March 2015. -

Geofest 2015 Download

Where booking details are given, bookings are essential GeoFest June 2015 If no cost is stated the event is free to attend 30th May to 31st August Saturday 30th May: Family Building Stones Roadshow Saturday 6th June: Guided Geology, Landscape and Lots of family friendly activities on the theme of stone and Building Stones Walk stone buildings. Follow a building stone trail around the ‘Ledbury Town’. Take a leisurely stroll around Ledbury and Arboretum, watch a dry stone wall being built and have a go the surrounding landscape with geologist Andrew Jenkinson What’s On! at building a mini wall, work with a local artist on a building and discover the relationship and history between the local stone creation, dig for treasure, make a badge and find out geology and the fabric of this historic town. lots of fascinating facts about Worcestershire stone. Start: 2pm at the Market House, High St, Ledbury, HR8 1DS Start: 11am at Bodenham Arboretum, Wolverley, DY11 5TB Est. finish: 5pm Cost: £2 adult / £1 child Finish: 3pm Bookings: 01938 820764 / [email protected] Cost: Arboretum admission fee (valid 11am - 5pm) Tuesday 9th June : Bite-Sized Talk ‘Conservation of the Bredon Hill Roman Coin Hoard’. A talk given by Museums Worcestershire curators. The Geopark at the Country Park Start: 1pm at Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum, Sunday 31st May Forgate Street, Worcester, WR1 1DT Finish: 1.30pm Cost: £2 Spend the day learning about your local Geopark, with plenty of rocks and fossils for Wednesday 10th June: Guided Walk you to see! Local geologists will be on hand ‘Bowhills and Pool Hall’. -

JBA Consulting Report Template 2015

1 Appendix B – SHELAA site screening tables 1.1 Malvern Hills District Proportion of site shown to be at risk (%) Area of site Risk of flooding from Historic outside surface water (Total flood of Flood Site code Location Area (ha) Flood Zones (Total %s) %s) map Zones FZ 3b FZ 3a FZ 2 FZ 1 30yr 100yr 1,000yr (hectares) CFS0006 Land to the south of dwelling at 155 Wells road Malvern 0.21 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 6% 0% 0.21 CFS0009 Land off A4103 Leigh Sinton Leigh Sinton 8.64 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% <1% 4% 0% 8.64 CFS0011 The Arceage, View Farm, 11 Malvern Road, Powick, Worcestershire, WR22 4SF Powick 1.79 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.79 CFS0012 Land off Upper Welland Road and Assarts Lane, Malvern Malvern 1.63 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.63 CFS0016 Watery Lane Upper Welland Welland 0.68 0% 0% 0% 100% 4% 8% 26% 0% 0.68 CFS0017 SO8242 Hanley Castle Hanley Castle 0.95 0% 0% 0% 100% 2% 2% 13% 0% 0.95 CFS0029 Midlands Farm, (Meadow Farm Park) Hook Bank, Hanley Castle, Worcestershire, WR8 0AZ Hanley Castle 1.40 0% 0% 0% 100% 1% 2% 16% 0% 1.40 CFS0042 Hope Lane, Clifton upon Teme Clifton upon Teme 3.09 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3.09 CFS0045 Glen Rise, 32 Hallow Lane, Lower Broadheath WR2 6QL Lower Broadheath 0.53 0% 0% 0% 100% <1% <1% 1% 0% 0.53 CFS0052 Land to the south west of Elmhurst Farm, Leigh Sinton, WR13 5EA Leigh Sinton 4.39 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 4.39 CFS0060 Land Registry.