Clergy in Battle and on Campaign 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

The Alfred Jewel, an Historical Essay, Earle John, 1901

F — — ALFEED JEWEL. tAv£S 3JD-6/. THE — THJ!; ALFIiED JEWEL. TIMES. TO THE EDITOR OF THE TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES. have been treading it is oir -Where so many angels Sir, —Mr. Elworthy would appear to be incapable of hnmble student to ventnre in. &tm, apprehending " perhaps rmwise for a my particular predicament in this Five another guess at the \"^^he worth whUe to make o'clock tea" controversy over the " Al frcd Jewel " jewel. which simply is that the traces of Oriental truth about the Alfred influence to be Musgrave, a Fellow of the Royal observed in its form and decoration support Professor Since 1698, when Dr. the the first notice of the jewel m Earle's contention that it was meant to be worn on a Society, published Tnmsactions"(No 247) It has been helmet. Surely this very humble suggestion is deserving f< Sophi-l " have been (1) an amulet of some consideration, especially as the " Alfred Jewel en^.ested that the jewel may a pendant to a chaan or was fastened to whatever it was attached in the same Musgrave's suggestion) ; (2) mT " " " of a roller for a M.S. ; manner as the two parts—the knop" and the flower • or head (3) an umbilicus, collar book-pomter (5) the head of a ; —of the Mo(n)gol torn were, and are, fastened together. the' top of a stilus ; U) sceptre standard; (7) the head of a ; After Professor Earle's suggestion of the purpose of 6 the top of a xs tbe " for .Alfred's helmet. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Diocese of Durham: Diocesan Synod, May 21 2010 Presidential Address

Diocese of Durham: Diocesan Synod, May 21 2010 Presidential Address: The Bishop of Durham, the Rt Revd N. T. Wright, DD Some of you, older synodical hands than I, have seen bishops come and go over a long period, and no doubt you tick them off one by one in your mind, perhaps even carving another notch on the end of the pew. But for me this is a strange moment, and also sad. This isn’t the moment for farewells; we shall come to that in July. But this will be my last Diocesan Synod, and I want to pay grateful tribute to those who have faithfully carried the administrative work of the Diocese over the last seven years, not least the Diocesan Secretary and his colleagues in the office, the successive Chairs of the Houses of Clergy and Laity, and the DBF and especially its Chair, and to you in Synod past and present. Our new Diocesan Annual Report speaks powerfully, in its style and presentation as well as its content, of the energy and clarity upon which we now can call, so that even in financially challenging circumstances we can hold our heads up and do a cheerful and professional job. My deep gratitude to all those involved. I shall say more ‘thank-yous’ on another occasion. But today, as we reflect on synodical business in particular, there is one theme which I see as urgently necessary. I chose Romans 14 as our reading for this morning’s worship to set the stage for this, and I’d be grateful if we could turn back to it now. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses During the Middle Ages

Geography and circulation of artistic models The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses during the Middle Ages Cristina DAGALITA ABSTRACT In 1084, Bruno of Cologne established the Grande Chartreuse in the Alps, a monastery promoting hermitic solitude. Other charterhouses were founded beginning in the twelfth century. Over time, this community distinguished itself through the ideal purity of its contemplative life. Kings, princes, bishops, and popes built charterhouses in a number of European countries. As a result, and in contradiction with their initial calling, Carthusians drew closer to cities and began to welcome within their monasteries many works of art, which present similarities that constitute the identity of Carthusians across borders. Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter, Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol monastery church, 1386-1401 The founding of the Grande Chartreuse in 1084 near Grenoble took place within a context of monastic reform, marked by a return to more strict observance. Bruno, a former teacher at the cathedral school of Reims, instilled a new way of life there, which was original in that it tempered hermitic existence with moments of collective celebration. Monks lived there in silence, withdrawn in cells arranged around a large cloister. A second, smaller cloister connected conventual buildings, the church, refectory, and chapter room. In the early twelfth century, many communities of monks asked to follow the customs of the Carthusians, and a monastic order was established in 1155. The Carthusians, whose calling is to devote themselves to contemplative exercises based on reading, meditation, and prayer, in an effort to draw as close to the divine world as possible, quickly aroused the interest of monarchs. -

Of St Cuthbert'

A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham by Ruth Robson of St Cuthbert' 1. Market Place Welcome to A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham, part of Durham Book Festival, produced by New Writing North, the regional writing development agency for the North of England. Durham Book Festival was established in the 1980s and is one of the country’s first literary festivals. The County and City of Durham have been much written about, being the birthplace, residence, and inspiration for many writers of both fact, fiction, and poetry. Before we delve into stories of scribes, poets, academia, prize-winning authors, political discourse, and folklore passed down through generations, we need to know why the city is here. Durham is a place steeped in history, with evidence of a pre-Roman settlement on the edge of the city at Maiden Castle. Its origins as we know it today start with the arrival of the community of St Cuthbert in the year 995 and the building of the white church at the top of the hill in the centre of the city. This Anglo-Saxon structure was a precursor to today’s cathedral, built by the Normans after the 1066 invasion. It houses both the shrine of St Cuthbert and the tomb of the Venerable Bede, and forms the Durham UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Durham Castle and other buildings, and their setting. The early civic history of Durham is tied to the role of its Bishops, known as the Prince Bishops. The Bishopric of Durham held unique powers in England, as this quote from the steward of Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1284-1311, illustrates: ‘There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.’ The area from the River Tees south of Durham to the River Tweed, which for the most part forms the border between England and Scotland, was semi-independent of England for centuries, ruled in part by the Bishop of Durham and in part by the Earl of Northumberland. -

![Diocese of Salisbury Statement of Needs [Jun 2021]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5257/diocese-of-salisbury-statement-of-needs-jun-2021-925257.webp)

Diocese of Salisbury Statement of Needs [Jun 2021]

Diocese of Salisbury: Statement of Needs 2021 CREDIT: Max Trafford ‘Love bade me welcome’ CREDIT: Sally Wilson CREDIT: Ash Mills As a Diocese we are committed to the local They capture the hospitable heart of Anglicanism, with courage, vision and holiness to renew its Formed by the union of two ancient sees, All Church traditions find a home here and honouring the Five Guiding Principles, church and its ongoing evolution, with important aspects of which were worked out promise for a beloved place and its people. Sherborne and Ramsbury, the removal of the we encourage service and growth rooted in and to the flourishing of the small new worshipping communities working in here in Salisbury – not only by Herbert, but Diocesan seat from Old Sarum to the new city prayerful attention to God’s call upon every number of parishes with alternative partnership with the parishes that remain our contemporaries John Jewel and Richard Hooker, The Church in this Diocese continues to be of Salisbury some eight hundred years ago is a person. All ministries are valued equally, we episcopal oversight. core. In the church doorway of one of these, who defined our church’s breadth and reach: nurtured by extraordinarily deep roots, with historic precedent for our current readiness to nurture a culture of collaborative working St Andrew’s Bemerton, is etched the words not by its limits, but its centre in Christ. some of the longest continually inhabited places develop and grow. Even the old, eternal rocks at all levels. In this description, we hope to give a “Love bade me welcome” – composed by in Britain. -

Prayer Pilgrimage

Prayer Pilgrimage This month the Benefice of Dorchester with the Winterbournes looks forward to the arrival of new Team Rector of Dorchester, Revd Canon Thomas Woodhouse. He and his family will be formally welcomed at the service of Institution, Induction and Installation on Wednesday 26th February, 7pm in St Mary’s Church, Edward Road (where Thomas will be based). However, prior to that, he will be travelling the patch by way of a Prayer Pilgrimage to which all are invited in their particular context, or if more convenient to one of the other churches in the team. Thomas writes: My desire during this short Prayer On the three days we will be having lunch at about Thomas Pilgrimage is to visit the nine 1230 in the following pubs and people are Woodhouse Anglican churches in the welcome to join us: Coach and Horse, Dorchester Team and Valley Winterbourne Abbas; The Royal Oak, High West &Valence benefice, and spend time praying with each Street, Dorchester [aka Wetherspoons – Ed.]; and worshipping community ahead of my Institution, The Wise Man, West Stafford. Induction and Installation at St. Mary’s on the evening of the 26th February 2014. I look forward to joining you as your Team Rector and to sharing in your ministry. I could visit the Meeting at 10am, 12noon and 2pm means that we get churches on my own but it will be more fun to do the best of the day; it also means Kate and I can be it in company! with the girls at the beginning and end of their first three days in new schools. -

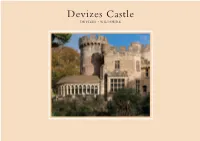

Devizes Castle DEVIZES • WILTSHIRE

Devizes Castle DEVIZES • WILTSHIRE Devizes Castle DEVIZES • WILTSHIRE The principal part of a magnificent Grade I listed Castle set in an elevated position with far reaching views Pewsey 12 miles (London Paddington from 59 minutes) Chippenham 12 miles (London Paddington from 68 minutes) Marlborough 14 miles • M4 Junction 15, 19 miles A303 16 miles (Distances and times approximate) Reception Hall • Kitchen/breakfast room • Sitting room • Drawing room • Dining room • Library • Study Long Gallery • Fernery • Secondary kitchen • Utility room • Boot room • Large Cellar and storage rooms • WC Two principal bedroom suites • Additional en-suite bedroom • Four further double bedrooms Two further bathrooms • Shower room • Three bedroom tower rooms Double car port • Formal gardens and grounds • Dry moat In all about 2.4 acres SAVILLS BATH SAVILLS COUNTRY DEPARTMENT Edgar House, 17 George Street, 33 Margaret Street, Bath, BA1 2EN London, W1G 0JD 01225 474 500 020 7016 3822 [email protected] [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text SITUATION Devizes Castle is located on the edge of the picturesque and historic market town of Devizes, in Wiltshire. Situated in an elevated and secluded position, the Castle commands charming chimney pot views to the east and rolling countryside views to the west. Devizes is home to an extensive range of everyday shops, including a Marks & Spencer food hall, recreational and educational facilities. The bustling market town of Marlborough is within a short drive whilst the fashionable cities of Bath (21 miles) and Salisbury (26 miles) provide further shops, social and cultural activities as well as famous historical sites and museums.