Gender Equality in Sport: Getting Closer Every Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going Home Again: a Family of Origin Approach to Individual Therapy

Head Office 30 Grosvenor Street, Neutral Bay, NSW 2089 Ph: 02 9904 5600 Fax: 02 9904 5611 Coming to grips with family systems theory in a [email protected] collaborative, learning environment. http://www.thefsi.com.au Going Home Again: A family of origin approach to individual therapy The paper was originally published in Psychotherapy in Australia Vol.14 No.1 pp. 12-18. SYNOPSIS: Family therapy with an individual and the relevance of family of origin themes are not new topics in the psychotherapy world. However the richness and depth of Dr Murray Bowen’s family systems and multigenerational approach to working with an individual has only been given scant attention in the Australasian context. Bowen’s theory retains a strong following and solid research attention in parts of North America. In this article the author explores Bowen’s model as it is applied to individual psychotherapy. Distinctions are made with traditional individual therapy where the in-session therapeutic relationship is the vehicle for change in contrast to Bowen’s focus on the natural system of the client’s own family. To illustrate, a case example of the author’s own experience of family of origin coaching when grieving the loss of her parents will be described. This will illustrate the beginnings of reworking a narrow caretaking role amongst siblings to a more multidimensional role of welcoming help from others. The impact of this shift on the author’s clinical work will be explored. When a family systems framework is referred to in the psychotherapy field it is most often thought of as an approach to working with the family group to address a relational problem or a symptom in a child. -

Guía De La Quiniela Guíaconcurso De Progolla Quiniela 2003 Concurso Progol 2094

Guía de la Quiniela GuíaConcurso de Progolla Quiniela 2003 Concurso Progol 2094 Local Visita LOCAL Visita JUAREZ vs MONTERREY LEON vs SAN LUIS Casillero Jornada 12 de la Liga MX. Juárez se ubica en el lugar 12 con 11 puntos, en su último juego ganó como local 1 a 0 a Casillero Jornada 12 de la Liga MX. León se ubica en 6to lugar con 15 unidades, perdió como visitante 2 a 0 contra Atlas. San 1 San Luis. Monterrey se encuentra en 2do lugar con 20 unidades, ganó como visitante 2 a 1 a S. Laguna. (Último 1 Luis se encuentra en 5to lugar con 16 puntos, ganó como visitante 2 a 1 a Toluca. (Último resultado: León 2-0 San Luis resultado: Juárez 1-6 Monterrey ) ) GUADALAJARA vs ATLAS S LAGUNA vs MAZATLAN Casillero 2 Jornada 12 de la Liga MX. Guadalajara se encuentra en 9no lugar con 14 unidades, empató como visitante 0 a 0 contra Casillero 2 Jornada 12 de la Liga MX. S. Laguna se encuentra en el lugar 10 con 12 puntos, perdió como local 2 a 1 contra Águilas. Atlas se ubica en 4to lugar con 19 puntos, ganó como local 2 a 0 a León. (Último resultado: Atlas 0-1 Monterrey. Mazatlán se encuentra en el lugar 11 con 11 unidades, empató como visitante 0 a 0 contra Tijuana. (Último Guadalajara ) resultado: Mazatlán 0-0 S. Laguna) AGUILAS vs PUMAS TIGRES vs NECAXA Casillero 3 Jornada 12 de la Liga MX. Águilas se ubica en 1er lugar con 21 puntos, empató como local 0 a 0 contra Guadalajara. -

Issue 53, November/December 2014

IInnssttaanntt UUppddaattee ISSUE 53 NOVEMBER/ DECEMBER 2014 To: ALL WSF MEMBER NATIONAL FEDERATIONS cc: WSF Regional Vice-Presidents, WSF Committee Members, WSA, PSA, Accredited Companies WSF ELECTS NEW BOARD Meanwhile, Hugo Hannes (Belgium) and Mohamed The 44th World Squash Federation AGM and El-Menshawy (Egypt) were re-standing and both Conference, held this year alongside the US Open in were re-elected. The third Vice-President place went Philadelphia, included a two-day conference which to Canadian Linda MacPhail, Secretary General of the featured presentations from key people from outside Pan-American Squash Federation [pictured with (L to squash to provide interesting insights and their R) Mohamed El-Menshawy, President Ramachandran experiences from the wide world of sport and related and Hugo Hannes]. organisations. WSF President N Ramachandran, commented: These included diverse topics such as governance, "Heather Deayton (pictured with Ramachandran) has digital marketing, interacting with communities and been a wonderful member of the WSF team and I am assessment solutions amongst others. very sorry to lose her. However, Linda MacPhail is a These included an exciting new film-based great addition, and it is a pleasure to welcome back programme for referee assessment and education Hugo and Mensh. which was demonstrated by Indian National Coach "These are exciting Major Maniam to the great interest of delegates. times for squash and Along with general business the centrepiece of the having spent the last AGM was the few days with -

Instant Update

Issue 20 World Squash Federation June 2008 Instant Update WSF MEETS IOC TO DISCUSS OLYMPIC BID WSF President Jahangir Khan , together with Emeritus President Susie Simcock and Secretary General Christian Leighton , met IOC Sports Director Christophe Dubi during this month's Sport Accord in Athens, to discuss Squash's bid to join the programme for the 2016 Olympic Games . The meeting was called by the IOC Sports Department with the objective of appraising the next steps regarding the 2008/09 review process and providing short-listed IFs the opportunity (individually) to ask questions on the process or other topics. The WSF was asked to name competitions that the Programme Commission should visit as part of the Observation Programme. Invitations will be extended to the 2008 Men's & Women's World Opens in Manchester in October. The presentations from short-listed IFs to the Executive Board will be made on 15-16 June 2009 in Lausanne. JAHANGIR KHAN HONOURED A touching “Spirit of Sport” award ceremony kicked off the AGM of the General Association of International Sports Federations in Athens, at which 83 IFs and international organisations were represented. The award recognises those who, through their unique commitment and humanitarian spirit, have made an exceptional and lasting contribution to the pursuit of sports excellence, sportsmanship and sport participation. WSF President Jahangir Khan received the 2008 GAISF Award from GAISF President Hein Verbruggen - alongside World Chess Federation (FIDE) Honorary President Florencio Campomanes -

99B.61 Bona Fide Contests. 1. a Person May Conduct, Without A

1 SOCIAL AND CHARITABLE GAMBLING, §99B.61 99B.61 Bona fide contests. 1. A person may conduct, without a license, any of the contests specified in subsection 2, and may offer and pay awards to persons winning in those contests whether or not entry fees, participation fees, or other charges are assessed against or collected from the participants, if all of the following requirements are met: a. A gambling device is not used in conjunction with or incident to the contest. b. The contest is not conducted in whole or in part on or in any property subject to chapter 297, relating to schoolhouses and schoolhouse sites, unless the contest and the person conducting the contest has the express written approval of the governing body of that school district. c. The contest is conducted in a fair and honest manner. d. A contest shall not be designed or adapted to permit the operator of the contest to prevent a participant from winning or to predetermine who the winner will be. e. The object of the contest must be attainable and possible to perform under the rules stated. f. If the contest is a tournament, the tournament operator shall prominently display all tournament rules. 2. A contest, including a contest in a league or tournament, is lawful only if it falls into one of the following event categories: a. Athletic or sporting events. Events in this category include basketball, volleyball, football, baseball, softball, soccer, wrestling, swimming, track and field, racquetball, tennis, squash, badminton, table tennis, rodeos, horse shows, golf, bowling, trap or skeet shoots, fly casting, tractor pulling, rifle, pistol, musket, or muzzle-loader shooting, billiards, darts, archery, and horseshoes. -

Nielsen Sports Women’S Football 2019 with Supporting Social Media Insights from Introduction

NIELSEN SPORTS WOMEN’S FOOTBALL 2019 WITH SUPPORTING SOCIAL MEDIA INSIGHTS FROM INTRODUCTION By almost any measure, the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup is poised to be the biggest yet. France will host the eighth edition of the tournament across nine cities – Lyon, Grenoble, Le Havre, Montpellier, Nice, Paris, Reims, Rennes and Valenciennes. With prime-time coverage expected across Europe, viewership is set to be up on the last tournament. At the same time, genuine commercial momentum is building with FIFA partners and team sponsors, notably Adidas and Nike, launching the most ambitious activation programmes yet seen for a women’s football event. Women’s club football is also growing around the world, an important development which looks set to ensure there is less of a spike in interest in women’s football around major international events like the World Cup as the club game sustains interest in the periods between them. There have been record attendances over the last year in Mexico, Spain, Italy and England, with rising interest levels and unprecedented investment from sponsors, while at a regional level, in Europe, UEFA is this season hosting the Women’s Champions League final in a different city from the men’s event for the first time. This report, put together by Nielsen Sports and Leaders, offers a snapshot of the health of women’s football as the World Cup gets underway, examining current interest levels, the makeup of fans and what the future may bring as it increasingly professionalises. On the eve of the FIFA Women’s World Cup, we have also worked with Facebook to look at interest in the women’s game across its platforms. -

Salary Disparities Between Male and Female Head Coaches

Salary Disparities Between Male and Female Head Coaches Salary Disparities Between Male and Female Head Coaches: An Investigation of the NCAA Power Five Conferences Alex Traugutt University of Northern Colorado Nicole Sellars University of Northern Colorado Alan L. Morse University of Northern Colorado 40 Traugutt, Sellars, and Morse Abstract Coaching salaries within intercollegiate athletics have increased tremendously over the past decade. This has led to continued and increased criticisms of current gender constructs within the NCAA and specifically the way in which coaches are compensated. The primary purpose of this study was to determine whether gender was a significant predictor of compensation for basketball coaches of men's and women's programs at the Division I level, while also assessing a variety of revenue and productivity variables. Results indicated that gender was not a statistically significant predictor of compensation. Rather, a host of revenue-specific variables were found to be the primary drivers of compensation for both male and female coaches. 41 Salary Disparities Between Male and Female Head Coaches Salary Disparities Between Male and Female Head Coaches: An Investigation of the NCAA Power Five Conferences Disparities in the wages paid to males and females have been well documented and publicized throughout history. These differentials have resulted in continued and increased criticisms of gender-based societal constructs. In the sport setting, while the earnings gap between men’s and women’s head coaches at the collegiate level is far from unique, little research focused on college basketball has been done to determine what influences these disparities. Consider the salaries paid to the University of Florida head basketball coaches Amanda Butler and Mike White. -

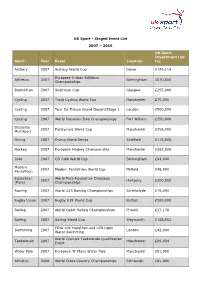

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Issue 44, May/June 2013

IInnssttaanntt UUppddaattee ISSUE 44 MAY/JUNE 2013 To: ALL WSF MEMBER NATIONAL FEDERATIONS cc: WSF Regional Vice-Presidents, WSF Committee Members, WSA, PSA, Accredited Companies ST PETERSBURG AWAITS May 29 is a critical date for squash. Last December we presented our case to the IOC’s Programme Commission and this day in May we shall do so to the IOC Executive Board in St Petersburg, Russia, along with the other shortlisted sports for the place on the programme of the 2020 Olympic Games. The presentation group will be led by WSF President Ramachandran and features our two world champions Nicol David and Ramy Ashour, whose passion and charisma are sure to impress the IOC President Jacques Rogge and his fourteen IOC Board colleagues. The bid film will be shown – it features the two players and has already been viewed nearly 110,000 times, along with the video giving a snapshot of the 185 countries that play squash (you can see both at http://www.worldsquash.org/ws/?p=10564) – along with a new film, that is being finished featuring innovation, broadcast and presentation. The spoken presentations will be accompanied by over 70 great slides illustrating the points made. What happens next is not confirmed. Originally it was stated that one sport would be recommended for ratification by the full IOC membership but indications now are that a few sports may be put forward for the final vote. That will be made clear on the evening of 29th May and we must hope that we are there for the final decision in Buenos Aires on 8th September. -

Health Coaching Case Report: Optimizing Employee Health and Wellbeing in Organizations Shannon Yocum M.A., NBC-HWC University of Minnesota, Earl E

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 12 Article 8 Issue 2 Summer/Fall 2019 July 2019 Health Coaching Case Report: Optimizing Employee Health and Wellbeing in Organizations Shannon Yocum M.A., NBC-HWC University of Minnesota, Earl E. Bakken Center for Spirituality and Healing, [email protected] Karen Lawson MD, ABIHM, NBC-HWC University of Minnesota, Earl E. Bakken Center for Spirituality and Healing, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Alternative and Complementary Medicine Commons, Business Commons, and the Mental and Social Health Commons Recommended Citation Yocum, Shannon M.A., NBC-HWC and Lawson, Karen MD, ABIHM, NBC-HWC (2019) "Health Coaching Case Report: Optimizing Employee Health and Wellbeing in Organizations," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.22543/0733.122.1266 Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol12/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Health Coaching Case Report: Optimizing Employee Health and SHANNON YOCUM MINNEAPOLIS-ST. PAUL, Wellbeing in Organizations MN, USA KAREN LAWSON MINNEAPOLIS-ST. PAUL, MN, USA Abstract Health and wellbeing of employees has a direct correlation to organizational performance. It is essential that organizations and successful leaders prioritize the health and wellbeing of all employees – from the C-suite to entry level positions. -

Determining the Boundary Between Executive Coaching and Psychotherapy

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses Organizational Dynamics Programs 5-20-2009 Determining the Boundary Between Executive Coaching and Psychotherapy Laura E. Strickler University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod Strickler, Laura E., "Determining the Boundary Between Executive Coaching and Psychotherapy" (2009). Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics Theses. 25. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/25 Submitted to the Program of Organizational Dynamics in the Graduate Division of the School of Arts and Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Organizational Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania Advisor: William S. Wilkinsky This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_msod/25 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Determining the Boundary Between Executive Coaching and Psychotherapy Abstract Accurate assessment of the boundary between executive coaching and psychotherapy is essential for a successful coaching experience. The similarities between the fields of executive coaching and psychotherapy present a challenge for coaching students who have yet to master the skills required to make the assessment and create a safe and appropriate environment in which a client may reach his or her goals. This thesis describes the similarities and differences of executive coaching and psychotherapy in order to define the working space shared by the two professions. It recommends skills for coaches that include the use of self, knowledge of the coach’s and the client’s level of self-awareness, and a basic understanding of psychology. -

Personal Assessment Coaching Guide

Personal Assessment Coaching Guide Center for the Army Profession and Leadership Fort Leavenworth KS October 2020 Table of Contents Document Overview ...................................................................................................................... 1 PART 1: THE ROLE OF THE COACH ....................................................................................................... 2 Coaching ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Coaching Fundamentals................................................................................................................. 2 What Coaching Is and Is Not .......................................................................................................... 3 Coach Presence ............................................................................................................................. 4 Communication ............................................................................................................................. 4 Speech Acts ................................................................................................................................... 6 Personal Awareness ...................................................................................................................... 6 Coaching Competencies and Activities ........................................................................................... 8 Coaching Competencies ................................................................................................................