Archaeological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public List of Active Licence Holders Tel No Sector / Classification

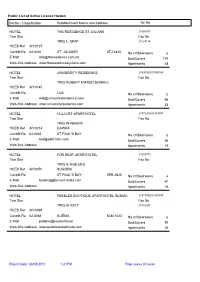

Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL THE RESIDENCE ST JULIANS 21360031 Two Star Fax No TRIQ L. APAP 21374114 HCEB Ref AH/0137 Contrib Ref 02-0044 ST. JULIAN'S STJ 3325 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 124 Web-Site Address www.theresidencestjulians.com Apartments 48 HOTEL UNIVERSITY RESIDENCE 21430360/21436168 Two Star Fax No TRIQ ROBERT MIFSUD BONNICI HCEB Ref AH/0145 Contrib Ref LIJA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 66 Web-Site Address www.universityresidence.com Apartments 33 HOTEL HULI CRT APARTHOTEL 21572200/21583741 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IN-NAKKRI HCEB Ref AH/0214 QAWRA Contrib Ref 02-0069 ST.PAUL'S BAY No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 56 Web-Site Address Apartments 19 HOTEL FOR REST APARTHOTEL 21575773 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IL-HGEJJEG HCEB Ref AH/0370 BUGIBBA Contrib Ref ST.PAUL'S BAY SPB 2825 No Of Bedrooms 4 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 40 Web-Site Address Apartments 16 HOTEL PEBBLES BOUTIQUE APARTHOTEL SLIEMA 21311889/21335975 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IX-XATT 21316907 HCEB Ref AH/0395 Contrib Ref 02-0068 SLIEMA SLM 1022 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 92 Web-Site Address www.pebbleshotelmalta.com Apartments 26 Report Date: 30/08/2019 1-21PM Page xxxxx of xxxxx Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL ALBORADA APARTHOTEL (BED & BREAKFAST) 21334619/21334563 Two Star 28 Fax No TRIQ IL-KBIRA -

St-Paul-Faith-Iconography.Pdf

An exhibition organized by the Sacred Art Commission in collaboration with the Ministry for Gozo on the occasion of the year dedicated to St. Paul Exhibition Hall Ministry for Gozo Victoria 24th January - 14th February 2009 St Paul in Art in Gozo c.1300-1950: a critical study Exhibition Curator Fr. Joseph Calleja MARK SAGONA Introduction Artistic Consultant Mark Sagona For many centuries, at least since the Late Middle Ages, when Malta was re- Christianised, the Maltese have staunchly believed that the Apostle of the Gentiles Acknowledgements was delivered to their islands through divine intervention and converted the H.E. Dr. Edward Fenech Adami, H.E. Tommaso Caputo, inhabitants to Christianity, thus initiating an uninterrupted community of 1 Christians. St Paul, therefore, became the patron saint of Malta and the Maltese H.E. Bishop Mario Grech, Hon. Giovanna Debono, called him their 'father'. However, it has been amply and clearly pointed out that the present state of our knowledge does not permit an authentication of these alleged Mgr. Giovanni B. Gauci, Arch. Carmelo Mercieca, Arch. Tarcisio Camilleri, Arch. Salv Muscat, events. In fact, there is no historic, archaeological or documentary evidence to attest Arch. Carmelo Gauci, Arch. Frankie Bajada, Arch. Pawlu Cardona, Arch. Carmelo Refalo, to the presence of a Christian community in Malta before the late fourth century1, Arch. {u\epp Attard, Kapp. Tonio Galea, Kapp. Brian Mejlaq, Mgr. John Azzopardi, Can. John Sultana, while the narrative, in the Acts of the Apostles, of the shipwreck of the saint in 60 AD and its association with Malta has been immersed in controversy for many Fr. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,582 Prezz/Price €2.70 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette L-Erbgħa, 3 ta’ Marzu, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Wednesday, 3rd March, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Avviżi tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar ....................................................................................... 1869 - 1924 Planning Authority Notices .............................................................................................. 1869 - 1924 It-3 ta’ Marzu, 2021 1869 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, -

Module 1 Gozo Today

Unit 1 - Gozo Today Josianne Vella Preamble: This first unit brings a brief overview of the Island’s physical and human geography, including a brief historic overview of the economic activities in Gozo. Various means of access to, and across the island as well as some of the major places of interest have been interspersed with information on the Island’s customs and unique language. ‘For over 5,000 years people have lived here, and have changed and shaped the land, the wild plants and animals, the crops and the constructions and buildings on it. All that speaks of the past and the traditions of the Islands, of the natural world too, is heritage.’ Haslam, S. M. & Borg, J., 2002. ‘Let’s Go and Look After our Nature, our Heritage!’. Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries - Socjeta Agraria, Malta. The Island of Gozo Location: Gozo (Għawdex) is the second largest island of the Maltese Archipelago. The archipelago consists of the Islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino as well as a few other uninhabited islets. It is roughly situated in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about 93km south of Sicily, 350 kilometres due north of Tripoli and about 290 km from the nearest point on the North African mainland. Size: The total surface area of the Islands amounts to 315.6 square kilometres and are among the smallest inhabited islands in the Mediterranean. With a coastline of 47 km, Gozo occupies an area of 66 square kilometres and is 14 km at its longest and 7 km at its widest. IRMCo, Malta e-Module Gozo Unit 1 Page 1/8 Climate: The prevailing climate in the Maltese Islands is typically Mediterranean, with a mild, wet winter and a long, dry summer. -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

46601932.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM BULLETIN OF THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALTA (2012) Vol. 5 : 57-72 A preliminary account of the Auchenorrhyncha of the Maltese Islands (Hemiptera) Vera D’URSO1 & David MIFSUD2 ABSTRACT. A total of 46 species of Auchenorrhyncha are reported from the Maltese Islands. They belong to the following families: Cixiidae (3 species), Delphacidae (7 species), Meenoplidae (1 species), Dictyopharidae (1 species), Tettigometridae (2 species), Issidae (2 species), Cicadidae (1 species), Aphrophoridae (2 species) and Cicadellidae (27 species). Since the Auchenorrhyncha fauna of Malta was never studied as such, 40 species reported in this work represent new records for this country and of these, Tamaricella complicata, an eastern Mediterranean species, is confirmed for the European territory. One species, Balclutha brevis is an established alien associated with the invasive Fontain Grass, Pennisetum setaceum. From a biogeographical perspective, the most interesting species are represented by Falcidius ebejeri which is endemic to Malta and Tachycixius remanei, a sub-endemic species so far known only from Italy and Malta. Three species recorded from Malta in the Fauna Europaea database were not found during the present study. KEY WORDS. Malta, Mediterranean, Planthoppers, Leafhoppers, new records. INTRODUCTION The Auchenorrhyncha is represented by a large group of plant sap feeding insects commonly referred to as leafhoppers, planthoppers, cicadas, etc. They occur in all terrestrial ecosystems where plants are present. Some species can transmit plant pathogens (viruses, bacteria and phytoplasmas) and this is often a problem if the host-plant happens to be a cultivated plant. -

Church Winter Time Comino 5.45 Fontana 6.00 Fontana 7.00 Fontana

Church Winter time Comino 5.45 Fontana 6.00 Fontana 7.00 Fontana 8.30 Fontana 10.30 Fontana 16.30 Għajnsielem - Lourdes Church 17.00 Għajnsielem – Lourdes Church 8.30 Għajnsielem - Parish 6.00 Għajnsielem - Parish 8.00 Għajnsielem - Parish 10.00 Għajnsielem - Parish 17.00 Għajnsielem - Saint Anthony of Padua (OFM) 6.00 Għajnsielem - Saint Anthony of Padua (OFM) 7.00 Għajnsielem - Saint Anthony of Padua (OFM) 8.30 Għajnsielem - Saint Anthony of Padua (OFM) 11.00 Għajnsielem - Saint Anthony of Padua (OFM) 17.30 Għarb - Parish 5.30 Għarb - Parish 7.00 Għarb - Parish 8.30 Għarb - Parish 10.00 Għarb - Parish 17.00 Għarb - Ta’ Pinu Sancturay 6.15 Għarb - Ta’ Pinu Sancturay 8.30 Għarb - Ta’ Pinu Sancturay 10.00 Għarb - Ta’ Pinu Sancturay 11.15 Għarb - Ta’ Pinu Sancturay 17.00 Għarb - Taż-Żejt 9.00 Għasri - Parish 6.00 Għasri - Parish 8.30 Għasri - Parish 10.00 Għasri - Parish 17.30 Għasri - Tal-Wied 17.00 Kerċem - Parish 6.00 Kerċem - Parish 7.00 Kerċem - Parish 8.30 Kerċem - Parish 10.30 Kerċem - Parish 18.00 Kerċem - Saint Lucy 7.00 Kerċem - Saint Lucy 10.30 Marsalforn - Saint Paul 8.00 Marsalforn - Saint Paul 10.00 Marsalforn - Saint Paul 11.00 Marsalforn - Saint Paul 18.00 Munxar 6.00 Munxar 7.00 Munxar 8.30 Munxar 11.00 Munxar 16.00 Nadur - Franciscan Sisters 6.15 Nadur - Franciscan Sisters 10.15 (English Mass) Nadur - Parish 5.15 Nadur - Parish 6.30 Nadur - Parish 8.00 Nadur - Parish 9.15 Nadur - Parish 10.30 Nadur - Parish 11.45 Nadur - Parish 16.30 Nadur - Parish 19.00 Nadur - Sacred Heart 7.00 Qala - Conception Church 6.00 Qala - Parish -

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr. Carl Rasmussen MAY 11-22, 2021 organized by Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome / May 11-22, 2021 Malta Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MAY 11-22, 2021 Fri 14 May Ferry to POZZALLO (SICILY) - SYRACUSE – Ferry to REGGIO CALABRIA Early check out, pick up our box breakfasts, meet the English-speaking assistant at our hotel and transfer to the port of Malta. 06:30am Take a ferry VR-100 from Malta to Pozzallo (Sicily) 08:15am Drive to Syracuse (where Paul stayed for three days, Acts 28.12). Meet our guide and visit the archeological park of Syracuse. Drive to Messina (approx. 165km) and take the ferry to Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland (= Rhegium; Acts 28:13, where Paul stopped). Meet our guide and visit the Museum of Magna Grecia. Check-in to our hotel in Reggio Calabria. Dr. Carl and Mary Rasmussen Dinner at our hotel and overnight. Greetings! Mary and I are excited to invite you to join our handcrafted adult “study” trip entitled Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Sat 15 May PAESTUM - to POMPEII Martyrdom in Rome. We begin our tour on Malta where we will explore the Breakfast and checkout. Drive to Paestum (435km). Visit the archeological bays where the shipwreck of Paul may have occurred as well as the Island of area and the museum of Paestum. Paestum was a major ancient Greek city Malta. Mark Gatt, who discovered an anchor that may have been jettisoned on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). -

Rolex Middle Sea Race - 2019

PORTS AND YACHTING DIRECTORATE LOCAL NOTICE TO MARINERS No 125 of 2019 Our Ref: TM/PYD//220/94 Vol. II 23 September 2019 Rolex Middle Sea Race - 2019 The Ports and Yachting Directorate, Transport Malta, notifies that the Royal Malta Yacht Club will be holding the Rolex Middle Sea Race on Saturday, 19 th October 2019. In addition a coastal race will also be held on Wednesday 16th October 2019. The race programme is as follows: a. Wednesday, 16th October 2019 The coastal race starts at 1000 hours. The start is from Marsamxett Harbour, at an imaginary line from the tower of Il-Fortizza ta’ Tigne to the corner of the bastion on the western side of Il-Fossa in Valletta. When they exit Marsamxett Harbour they will proceed, depending on the weather conditions, either to Comino and/or Gozo or to Munxar and/or Filfa and finish at Marsamxett Harbour. Mariners are requested to keep the Marsamxett fairway clear during the start of the coastal race and to keep a sharp lookout during the remaining hours of Wednesday 16th October 2019. b. Saturday, 19 th October 2019 The Rolex Middle Sea Race starts at approximately 1100 hours. The start is from the Grand Harbour, at an imaginary line from an inflatable buoy near Saint Angelo Point to the Valletta Saluting Battery mast. The yachts shall then proceed in a North - Easterly direction along the Channel in the Grand Harbour to an inflatable buoy, bearing the sponsor’s logo, positioned outside the Saint Elmo Breakwater. The buoy shown as 1 on attached charts 1 will be in the following approximate position: LATITUDE (N) LONGITUDE (E) 35 ⁰ 54’.160 014 ⁰ 31’.540 The yachts shall then proceed in a North – Westerly direction towards St George’s shoals where a second inflatable buoy, bearing the sponsor’s logo will be positioned. -

1 General Characteristics

CENSUS OF AGRICULTURE 2010 National Statistics Office, Malta 2012 Published by the National Statistics Office Lascaris, Valletta VLT 2000 Malta Tel.: (+356) 2599 7000 Fax: (+356) 2599 7205 / 2599 7103 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.nso.gov.mt CIP Data Census of Agriculture 2010. – Valletta: National Statistics Office, 2012 xxviii, 119p. ISBN: 978-99957-29-33-2 For further information, please contact: Unit B3: Agricultural and Fisheries Statistics Directorate B: Business Statistics National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta VLT 2000 Malta Tel.: (+356) 2599 7339 Our publications are available from: Unit D2: External Cooperation and Communication Directorate D: Resources and Support Services National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta VLT 2000 Malta Tel: (+356) 2599 7219 Fax: (+356) 2599 7205 Printed in Malta by the Government Printing Press CONTENTS Page Foreword xi Commentary xii Methodology xix Chapter 1 – General Characteristics 1 Chapter 2 – Land Use 29 Chapter 3 – Livestock 53 Chapter 4 – Labour Force 79 Chapter 5 – Machinery and Equipment 99 Chapter 6 – Irrigation 103 Chapter 7 – Ploughing and Manure 109 Chapter 8 – Typology of Agricultural Holdings 113 Page Chapter 1 – General Characteristics 1.1 Distribution of area declared by farmers by type of area, by district and 3 locality C1.1 Percentage distribution of area by type 5 1.2 Distribution of utilised agricultural area by type of tenure by locality 6 C1.2 Percentage distribution of UAA by type of tenure 8 1.3 Distribution of utilised agricultural area by type and locality -

Gozo Observer

Of Salmonellae and Salmonella Gozo LORANNE VELLA* Introduction had to carry out the study, I realized that Gozo was just small enough and had just the right I will always remember the summer of 1993 as number of cattle farms for my project. There a particularly hot and humid season, not to were other advantages: my father could help mention my experiences chasing, with gloved to take me around the various farms for the hands and booted feet, a few hundred samples (since I had no car) and I could speak apprehensive and distrustful cows for some the various Gozitan dialects, which made the stinking, fresh dung. The memories now are farmers more receptive. quite hilarious, but not then, at least not when the bulls or a rather angry cow had to be confronted. The Genus Salmonella Having always been rather keen on the study Salmonella is a group of bacteria consisting of of micro-organisms, I knew right from my more than 2000 different types (known as freshman year at the University of Malta, that serotypes or serovars); these are all potentially I wanted to work in a topic related to pathogenic to man and may cause microbiology for my undergraduate thesis. In gastroenteritis, septicaemia or enteric fever. 1991, I spent a whole summer reading Medline Salmonellae also infect many animal species, abstracts, but it was an article on Salmonella in including birds and reptiles. In man, infections one of my Medicine Digest copies that actually often result following ingestion of improperly caught my attention. Another reason that cooked animal products that have been encouraged me to undertake a study on previously contaminated with faecal matter Salmonella was the fact that no such studies on during processing. -

Petition Booklet

Referenda Act : Declaration for the holding of a Referendum We the undersigned persons, being registered as voters for the election of members of the House of Representatives, demand that the question whether the following provision of law, that is to say Framework for Allowing a Derogation Opening a Spring Hunting Season for Turtledove and Quail Regulations (Subsidiary Legislation 504.94 - Legal Notice 221 of 2010) should not continue in force, shall be put to those entitled to vote in a referendum under Part V of the Referendum Act. Electoral Name and Surname Signature ID Card Address (in full) Division Please return to 57/28 Triq Abate Rigord, Ta’ Xbiex XBX 1120 What spring hunting takes place in Malta? In view of the consistent lack of action by government and Dear Members, inertia on the European Commission’s part, the Coalition To hunt birds in spring, hunters apply for a license that allows believes it is time for the people to have their say through a them to shoot quails (summien) and turtle doves (gamiem) referendum to remove the law that allows hunting in spring. Thirteen Maltese organisations have decided to work for two weeks in April. Last spring about 9500 hunters were together to bring an end to spring hunting in Malta. licensed to shoot up to 11,000 turtle doves and 5000 quail Isn’t it unfair to deprive hunters of their hobby? The task of the Coalition for the Abolition of among themselves. The licence (previously €50) is free of Spring Hunting is to gather at least 34,000 signatures charge, and hunters are asked to report what they catch by Maltese bird hunters already have months in autumn and to petition the government to hold a referendum to sending an SMS to the relevant authority.