Channon Quinney Khomutova Matthews Authors Accepted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brian Sandoval Governor STATE OF

Bruce Breslow Brian Sandoval STATE OF NEVADA Department Director Governor DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY ATHLETIC COMMISSION Bob Bennett Executive Director Chairman: Anthony A. Marnell III Members: Francisco V. Aguilar, Skip Avansino, Pat Lundvall, Michon Martin TO THE COMMISSION AND THE PUBLIC: AGENDA A duly authorized meeting of the Nevada State Athletic Commission will be held on Wednesday, February 17, 2016, at 9:00 a.m. at the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Room 4500 Las Vegas, NV 89101. 1. Call to order. 2. Roll Call. 3. Public Comment. 4. Approval of the minutes of the meetings of December 17, 2015 and February 4, 2016 for possible action. 5. Adoption of the agenda for this meeting, for possible action. 6. Disclosures per NRS 281/281A. OLD BUSINESS: 1. Re‐hearing on appropriate discipline against mixed martial artist Wanderlei Silva, for possible action. CONSENT AGENDA: a. Date Requests 1. Request by Roy Englebrecht Promotions for the date of March 12, 2016 to promote a boxing event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on CBS Sports Network with a maximum of 7 fights and pending Executive Director Bob Bennett’s approval of the venue’s outdoor facilities, for possible action. 2. Request by World Series of Fighting for the date of April 2, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on NBC Sports Network, for possible action. 3. Request by Zuffa, LLC for the date of April 23, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas to be televised on PPV, for possible action. -

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Match Results

Match Results Date: 4/19/2014 Venue/Location: Amway Center -- Orlando, FL Promoter: UFC Commissioners Judge: Richard Bertrand Referee: John McCarthy Physician: Dr. Adam Brunson Commissioners Judge: Chris Lee Referee: Jorge Alonso Physician: Dr. George Panagakos Dr. Mark Williams, Chairman Judge: Jean Warring Referee: Jorge Ortiz Knockdown Timekeeper: Dr. Wayne Kearney Judge: Eliseo Rodriguez Referee: Herb Dean Alternate Referee Mr. Antonius DeSisto Judge: Hector Gomez Referee: Commissioners Present: Mr. Marco Lopez Judge: Tim Vannatta Referee: Mr. Tirso Martinez Judge: Derek Cleary Referee: Referee: Executive Director: Cynthia Hefren Asst. Executive Director: Frank Gentile Timekeeper(s): James Chittenden; Roy Silbert Event Type: MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Participants Federal ID Hometown Weight DOB Sch Rds Results Officials Suspensions and Remarks Claim form, knee, indefinite susp, neruo Referee: John McCarthy; Jack May 110-622 Costa Mesa, CA 252.5 lbs 4/14/1981 clearance 3 Judges: Jean Warring; Chris 1 Winner TKO 4:23 1st Lee; Richard Bertrand Referee stoppage from strikes Derrick Lewis 116-645 Houston, TX 256.0 lbs 2/7/1985 Rd Referee: Jorge Ortiz; Judges: Chas Skelly 101-842 Keller, TX 145.0 lbs 5/11/1985 2 3 Eliseo Rodriguez; Tim Winner by Majority Vannatta; Richard Green Suspension 180 days or Facial CT Marsid Bektic 105-060 Coconut Creek, FL 146.0 lbs 2/11/1991 Decision clearance Referee: Jorge Alonso; Ray Borg 127-020 Albuquerqu, NM 125.5 lbs 8/4/1993 3 3 Judges: Chris Lee; Hector Winner by Split Gomez; Derek Cleary Dustin Ortiz 121-691 -

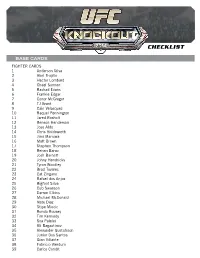

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

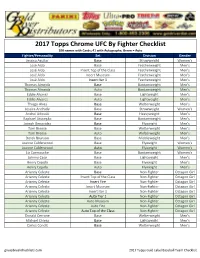

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

1 Robbie Lawler 2 Conor Mcgregor 3 Paige Vanzant

BASE CARDS 1 Robbie Lawler 2 Conor McGregor 3 Paige VanZant 4 Georges St-Pierre 5 Anderson Silva 6 Ronda Rousey 7 Daniel Cormier 8 Matt HugHes 9 Fabricio Werdum 10 Chuck Liddell 11 Forrest Griffin 12 Lyoto MacHida 13 BJ Penn 14 TJ DillasHaw 15 Frank Mir 16 MiesHa Tate 17 Frankie Edgar 18 Cris Justino 19 Arianny Celeste 20 José Aldo 21 RasHad Evans 22 Rafael Dos Anjos 23 CM Punk 24 Joanna Jędrzejczyk 25 Dominick Cruz 26 Demetrious JoHnson 27 Stipe Miocic 28 Cláudia GadelHa 29 Tyron Woodley 30 StepHen Thompson 31 MicHelle Waterson 32 Joanne Calderwood 34 Luke RockHold 35 Antonio Silva 36 Nate Diaz 37 Henry Cejudo 38 Cody Garbrandt 39 JosepH Benavidez 40 Amanda Nunes 41 Anthony JoHnson 42 Junior Dos Santos 43 Donald Cerrone 44 Eddie Alvarez 45 KHabib Nurmagomedov 46 Holly Holm 47 Carlos Condit 49 Rose Namajunas 50 Cat Zingano 51 Yoel Romero 52 Jim Miller 53 Neil Magny 54 Glover Teixeira 55 Al Iaquinta 56 Jessica Aguilar 57 Joe Lauzon 58 Nick Diaz 59 JoHn Dodson 60 Ovince Saint Preux 61 Andrew SancHez 62 Robert WHittaker 63 Randa Markos 64 Julianna Peña 65 THiago Alves 67 Tecia Torres 68 JoHnny Case 69 Ryan Hall 70 Raquel Pennington 71 Mickey Gall 72 Jimmie Rivera 73 THomas Almeida 74 Sage Northcutt 75 Valentina Shevchenko 76 Karolina Kowalkiewicz 77 Jessica Andrade 78 CHas Skelly 79 Derek Brunson 80 Andrei Arlovski 81 JoHny Hendricks 82 MicHael Chiesa 83 Dustin Poirier 84 James Vick 85 Jessica Eye 86 Louis Smolka 87 Sara McMann 88 Alexa Grasso 89 Liz CarmoucHe 90 Demian Maia 91 Tony Ferguson 92 Cub Swanson 93 Max Holloway 94 JoHn Lineker -

Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Program Authorized to Offer Degree

Position Before Submission: Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Courtney C. Choi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Natalie Jolly, Chair Lawrence M. Knopp Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences © Copyright 2017 Courtney C. Choi University of Washington Abstract Position Before Submission: Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Courtney C. Choi Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Natalie Jolly, Ph.D. School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences The intent of this thesis is to explore existing gender norms in mixed martial arts cultures. Masculinity is particularly valorized in sport, creating tension for female athletes who are forced to balance masculine norms with feminine beauty ideals. While there is a robust literature on the intersections of mixed martial arts (MMA) and masculinity, female voices are rarely heard in that literature. My research goes beyond the work of others by incorporating female voices and perspectives. Grounded in gender constructionism, my thesis addresses how both male and female MMA fighters conceive of their and others’ participation in gendered terms, and how this informs their gender identities. My thesis further examines the intersections of masculinity and gender that are readily observable within MMA, and those that are less conspicuous or go largely unnoticed. Finally, my thesis explores how norms perpetuate gender stereotypes and highlight differences, as masculine norms persist in the fighting culture. The examination of gender norms in MMA contributes to a larger body of research concerning gender roles and norms in other social contexts. -

Pete Suazo Utah Athletic Commission Unified Rules Of

PETE SUAZO UTAH ATHLETIC COMMISSION GOVERNOR’S OFFICE OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT P.O. Box 146950 60 East South Temple, 3rd Floor Salt Lake City, UT 84114-6950 Office: 801-538-8876 Fax: 801-708-0849 UNIFIED RULES OF PROFESSIONAL MIXED MARTIAL ARTS 1. Definitions “Mixed martial arts” means unarmed combat involving the use, subject to any applicable limitations set forth in these Unified Rules and other regulations of the applicable Commission, of a combination of techniques from different disciplines of the martial arts, including, without limitation, grappling, submission holds, kicking and striking. “Unarmed Combat” means any form of competition in which a blow is usually struck which may reasonably be expected to inflict injury. “Unarmed Combatant” means any person who engages in unarmed combat. “Commission” means the applicable athletic commission or regulatory body overseeing the bouts, exhibitions or competitions of mixed martial arts. 2. Weight Divisions Except with the approval of the Commission, or its executive director, the classes for mixed martial arts contests or exhibitions and the weights for each class shall be: Strawweight up to 115 pounds Flyweight over 115 pounds to 125 Bantamweight over 125 to 135 pounds Women's Bantamweight over 125 to 135 pounds Featherweight over 135 to 145 pounds Lightweight over 145 to 155 pounds Welterweight over 155 to 170 pounds Middleweight over 170 to 185 pounds Light Heavyweight over 185 to 205 pounds Heavyweight over 205 to 265 pounds Super Heavyweight over 265 pounds In non-championship fights, there shall be allowed a 1 pound weigh allowance. In championship fights, the participants must weigh no more than that permitted for the relevant weight division. -

Rank Athlete Country Organisation Gender Type Division Point 1

Rank Athlete Country Organisation Gender Type Division Point 1 Muhammad Mokaev United Kingdom EMMAA English Mixed Martial Arts Association Male Senior Bantamweight 1679.0 2 Anna Gaul Germany GEMMAF Female Junior Jr Strawweight 1181.0 2 Murad Guseinov Bahrain Bahrain MMAF Male Senior Welterweight 1181.0 3 Omar Aliev Russia Russian MMA Union Male Junior Jr Light Heavyweight 1149.0 4 Milly Horkan United Kingdom EMMAA English Mixed Martial Arts Association Female Junior Jr Bantamweight 1097.0 5 Reo Yamaguchi Japan Japan MMAF Male Junior Jr Bantamweight 1009.0 6 Gani Adilserik Kazakhstan KZMMAF Male Junior Jr Flyweight 952.0 7 Fariz Abdalov Kazakhstan KZMMAF Male Junior Jr Flyweight 936.0 8 Sirazhudin Abdulaev Russia Russian MMA Union Male Junior Jr Featherweight 932.0 8 Nikita Kulshin Russia Russian MMA Union Male Junior Jr Lightweight 932.0 9 Talshyn Zhumatayeva Kazakhstan KZMMAF Female Junior Jr Lightweight 900.0 9 Magomed Tuchalov Russia Russian MMA Union Male Junior Jr Middleweight 900.0 10 Rustam Ashurbekov Russia Russian MMA Union Male Junior Jr Heavyweight 868.0 11 Magdalena Czaban Poland MMA Polska Stowarzyszenie Female Senior Atomweight 836.0 12 Yerulan Kabdulov Kazakhstan KZMMAF Male Junior Jr Strawweight 751.0 13 Shamsutdin Makhmudov Russia Russian MMA Union Male Senior Super Heavyweight 705.0 14 Murad Ibragimov Bahrain Bahrain MMAF Male Senior Flyweight 580.0 14 Emil Piatek Poland MMA Polska Stowarzyszenie Male Junior Jr Lightweight 580.0 14 Kamil Shaikhamatov Russia Russian MMA Union Male Junior Jr Welterweight 580.0 15 Błażej -

Announcement

Announcement Total 100 articles, created at 2016-08-26 00:02 1 Donald Trump calls Hillary Clinton a 'bigot' at Mississippi rally – video (1.39/2) Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump spoke to a rally in Mississippi on Wednesday evening and called political rival Hillary Clinton ‘a bigot’ 2016-08-25 16:02 1KB www.theguardian.com 2 Trump proclaims polls with black and Hispanic voters have gone 'way up' (1.02/2) Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump told rally-goers in Tampa on Aug. 24 that "the polls with African American folks and Spanish-speaking folks, the Hispanics, Latinos, have gone way up" in the last three weeks. 2016-08-25 18:26 975Bytes www.washingtonpost.com 3 Woman Dies After Falling 40 Feet From Zip Line in Delaware Video (1.02/2) A 59-year-old woman has died after falling approximately 40 feet from a zip line at the Lums Pond State Park in Delaware. 2016-08-25 18:23 1KB abcnews.go.com 4 Turkey warns Syrian Kurds to withdraw east of Euphrates (1.02/2) Turkey threatens further intervention in northern Syria unless Kurdish-led forces withdraw east of the River Euphrates within a week. 2016-08-25 18:03 3KB www.bbc.co.uk 5 WATCH: Black Coffee's son left overwhelmed by lesson on how to take care of a lady Black Coffee's young boy appears to be overwhelmed when his dad explains to him all the things that go into taking care of a lady, saying 2016-08-26 00:01 1KB www.timeslive.co.za 6 Memorial service for Inchanga shooting victims called off to allow for peace talks A joint memorial for two victims of factional fighting in Inchanga was postponed early on Thursday. -

25 Pro Fighters, Managers, and Coaches Reveal Their Best Tips to Land a Sponsorship by Solmadrid Vazquez Follow Me on Twitter Here

25 Pro Fighters, Managers, and Coaches Reveal Their Best Tips to Land a Sponsorship by Solmadrid Vazquez Follow me on Twitter here. Sponsorships can make or break you. The problem is, the process of landing a sponsorship is counter-intuitive. Being a great fighter is NOT enough. I’m sure you’ve seen fighters who land sponsors left and right. What’s their secret? How come they can get 27 sponsors in one day and you can’t even get one freakin’ rep to look at you? What THE hell is going on?! To get to this bottom of this conundrum, I contacted some of the best fighters, managers, and trainers in the game and asked them a simple question: “What is your #1 tip to land a sponsorship?” Each tip has a custom tweet link after it so feel free to share your favorite tips with your followers. Let’s Get Ready To Ruuuummmmbllllllleee!!! Frank Shamrock Frank Shamrock is a retired MMA Fighter. He was the first UFC Middleweight Champion and retired as the four-time defending undefeated champion. He was also the first WEC Light Heavyweight Champion, and the first Strikeforce Middleweight Champion. He was a brand spokesman for Strikeforce and is a Sports Commentator for Showtime. Frank can be found at his site, on Facebook, and on Twitter. My number one tip to landing a sponsorship is presenting yourself properly. Present a long-term consistent growth plan that somebody, or a sponsor, could attach themselves to, so you can show how you will grow together. “Present a long-term consistent growth plan.” Tweet this. -

Undefeated Olympians Collide As Champion Ronda Rousey Meets Sara Mcmann at Ufc® 170 Saturday, February 22

UNDEFEATED OLYMPIANS COLLIDE AS CHAMPION RONDA ROUSEY MEETS SARA MCMANN AT UFC® 170 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 22 Las Vegas, Nevada – In what could prove to be her toughest challenge yet, UFC® women’s bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey (8-0, fighting out of Venice, Calif.) squares off against undefeated wrestling sensation Sara McMann (7-0, fighting out of Gaffney, SC) in a battle of Olympic medalists at UFC® 170 at the Mandalay Bay Events Center Saturday, Feb. 22. A bronze medal winner in Judo at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, Rousey recently defeated her bitter rival Miesha Tate at UFC 168 to retain the women’s bantamweight belt and remain the divison’s only champion. Now she takes on McMann, who comes in as the most decorated wrestler in the weight class, having also earned Olympic silver at the 2004 games in Athens in free- style wrestling. In addition to the Rousey-McMann tilt, (No. 3) Rashad Evans (19-3, fighting out of Boca Raton, Fla.), a former light heavyweight champion, battles the Strikeforce Heavyweight Grand Prix winner Daniel Cormier (13-0, fighting out of San Jose, Calif.) in his debut at the 205-pound weight class. Evans comes into the bout sporting consecutive wins over Dan Henderson and Chael Sonnen while Cormier is looking to keep his unblemished professional record and make a statement in his new division. The card also features Brazilian jiu-jitsu ace (No. 6) Demian Maia (18-5, fighting out of Sao Paulo, Brazil) matching up against Canadian prodigy and Georges-St. Pierre training partner (no. 4) Rory MacDonald (15-2, fighting out of Montreal, Canada) in a battle of Top 10-ranked welterweights. -

Entertainment Design in Mixed Martial Arts: Does Cage Size Matter?

Journal of Applied Sport Management Volume 11 Issue 2 Article 10 1-1-2019 Entertainment Design in Mixed Martial Arts: Does Cage Size Matter? Paul Gift Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jasm Part of the Business Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gift, Paul (2019) "Entertainment Design in Mixed Martial Arts: Does Cage Size Matter?," Journal of Applied Sport Management: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2. https://doi.org/10.18666/JASM-2019-V11-I2-9198 Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jasm/vol11/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Applied Sport Management by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/jasm. Journal of Applied Sport Management Vol. 11, No. 2, Summer 2019 https://doi.org/10.18666/JASM-2019-V11-I2-9198 Entertainment Design in Mixed Martial Arts Does Cage Size Matter? Paul Gift Abstract This paper investigates the effect of a change in cage size on fighter performance outcomes in Zuffa-owned mixed martial arts (MMA) promotions. Variation in cage size is observed through different events over time in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) and World Extreme Cagefighting (WEC). Results suggest that smaller cages lead to more fight finishes (knockouts and submissions) and higher rates of distance knockdowns and choke attempts, all exciting outcomes for viewers. But they also lead to a higher proportion of time with fighters pressed against the cage, a position some viewers may dislike.