Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

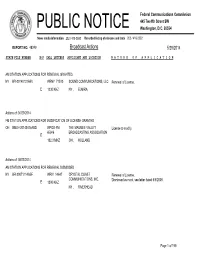

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

The English Take Control DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION

CHAPTER 3 • SECTION 4 New Netherland As you read in Chapter 2, in the early 1600s the Dutch built the colony of New Netherland along the Hudson River in what is now New York State. The colony’s largest town, New Amsterdam, was founded on Manhattan Island in 1625. New Amsterdam was built to defend the Dutch More About . West India Company’s fur trading settlements along the Hudson River. Peter Stuyvesant, the colony’s governor, expanded New Netherland by Religious Refugees taking over the nearby colony of New Sweden in 1655. The Swedes had settled the land along the Delaware River in 1638. in Pennsylvania The Dutch West India Company set up the patroon system to attract more In England, thousands of Quakers went settlers. A patroon was a person who brought 50 settlers to New Netherland. to jail for their beliefs, especially after As a reward, a patroon received a large land grant. He also received hunting, Charles II gained the throne in 1660. fishing, and fur trading privileges. The patroon system brought great wealth Some made their way to Maryland and to the colony’s elite. Massachusetts in the 1650s, but after The social system also included many slaves. Although their lives were William Penn founded a Quaker colony in harsh, they enjoyed some rights of movement and property ownership. 1681, many more arrived. A Tolerant Society In the 17th century the Netherlands had one of the Besides Quakers, several other small religious most tolerant societies in Europe. Dutch settlers brought this religious toleration to their colony. -

History and Genealogy of the Vreeland Family

.0^ . ^ovV : ^^^* • .rC^^'^.t.'^ . O .V . 4:^ "^^ o.* "^ v° *^' %- 'd- m^ ^^^ \ a/ "O* - '^^ .^'-^ "<*>. n"^ ,o«<.- -^^ ^ Vol •.°' ^^ aO ^ './ >:^^:- >. aV .^j^^^. Nicholas Garretson \'reeland. THHR BOOK: Wriltenarranged ^adaptgd BY ON E OF THEM WWW OIMT^oN VREELSIND Title parte and ofcher* di-awing/s by FR.flNCI5 WILLIAM Vl^EELflND^ Printed by CHflUNCELY H O L T- NOa7V^NDEPy%'" 3TIIEE.T • NEW YORK: HISTORY GENEALOGY of the VREELAND FAMILY Edited by NICHOLAS GARRETSON VREELAND HISTORICAL PUBLISHING CO. Jersey City, Nert) Jersey MDCCCCIX sT 1'^ \(\ •2> (At Copyright 1909 BY Nicholas G. Vrekland Cla.A,a3<* 112 JUL 28 1909 1 : table:contentsof CHAPTER. TITLE. PAGE. Foreword. 9 Preface. 10 PART FIRST — THE STORY OF HOLLAND. 1 In Day.s of Caesar 17 2 Fifteen Centuries of Struggle 20 3 The Dutch take Holland 21 4 Chaos leads to System 23 5 Dutch War Songs 24 Beggars of the Sea 24 Moeder Holland 29 Oranje Boven 30 6 Independence at Last 31 7 Holland and its People 33 8 Holland of To-day 41 PART SECOND — THE STORY OF AMERICA. 9 The American Birthright (Poem)... 49 10 In the New World, 1609-38 53 1 On Communipaw's Shore, 1646 57 12 Settlement of Bergen, 1660 59 13 Religion and Education 61 14 Battledore and Shuttlecock, 1664-74 63 15 Paulus Hook, 1800 66 16 From Youth to Manhood, 1840- 1909 69 17 Manners and Customs 73 18 Nomenclature 76 19 The True Dutch Influence 83 20 Land Titles 90 PART THIRD — THE STORY OF THE VREELANDS. 2 An Old Vreeland Family 99 22 The Town Vreeland, in Holland 104 CONTENTS—Continued. -

Ulster County Area Transit Equal Employment

ULSTER COUNTY AREA TRANSIT EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY (EEO) PROGRAM 2019-2021 Ulster County Area Transit 1 Danny Circle Kingston, NY 12401 EEO Contact Director of Public Transportation (845) 340-3335 Nov 15, 2019 Table of Contents Section Page Section 1: EEO Policy Statement 1 Section 2: Dissemination 3 Section 3: Designation of Responsibility 4 Section 4: Recent Success 6 Section 5: Goals and Timetables 7 Section 6: Employment Practices 8 Section 7: EEO Complaint Process 9 Section 8: Appendices 10 A. Workforce Analysis and Goals by Job Title and Group B. EEO Job Categories C. Job Titles Included in Grade D. Salary Structure E. Organizational Chart F. EEO-4 Report G. Signed EEO Policy Statement H. U.S. Census Labor Force and Employment Characteristics I. EEO-1 Aggregate Report for Kingston and Ulster County J. Collective Bargaining Agreement with CSEA Unit 8950 K. Reasonable Accommodation Policy Handout L. Examples of External Dissemination M. County of Ulster Standards of Conduct edited showing EEO content only N. Employment Practices Statistical Data Examples 2 Section 1: Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Policy Statement Ulster County Area Transit, including its sub recipients and contractors (UCAT), affirms its commitment to treat all applicants for employment and employees equally without regard to race, religion, creed, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, veterans’ status, marital status or other class prohibited by local, State or Federal law. UCAT is an Equal Employment Opportunity employer. It is prohibited for UCAT or any of its employees to discriminate against an applicant for employment or another employee on the basis of race, color, and religious creed, sex, age, national origin, or any other basis prohibited by local, State or Federal law, or to be excluded from participation in, or denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any project, program, or activity funded in whole or in part through Federal financial assistance. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Commending Walter C. Maxwell Upon

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION commending Walter C. Maxwell upon the occasion of his designation for special honor by the Ulster Community College Foun- dation at its 2009 Gala Recognition Dinner WHEREAS, It is the practice of this Legislative Body to take note of and publicly acknowledge individuals of remarkable integrity and character who have inspired and brought pride to our majestic Empire State with their strong contributions to the community and model citizenship; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in full accord with its long- standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to commend Walter C. Maxwell upon the occasion of his designation for special honor by the Ulster Community College Foundation at its 2009 Gala Recognition Dinner at the Hillside Manor in Kingston, New York; and WHEREAS, Born in 1940 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Walter C. Maxwell graduated from Ellenville High School in 1959, and spent the next four years in the United States Air Force; and WHEREAS, After leaving the United States Air Force in 1963, Walter C. Maxwell attended Marist College, where he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Business in 1967; and WHEREAS, Walter C. Maxwell then worked at the Hudson River Valley Commission, a New York State agency responsible for environmental plan- ning for the river, and IBM in Kingston, where he was a financial analyst; and WHEREAS, In 1973, Walter C. Maxwell left IBM to join the family broad- cast business, which included WGHQ and WBPM, with his stepfather, Harry Thayer; he sold the business in 1999; and WHEREAS, Walter C. Maxwell has been the President of Historic Hudson Valley Radio Inc., a wireless communications tower management company serving the Kingston, New York region, since 1975, and is also involved in operating a public radio company, Kingston Community Radio, to serve Ulster and Northern Dutchess Counties; and WHEREAS, Despite his busy professional life, Walter C. -

Everyday Life in a Dutch Colony

Everyday Life in a Dutch Colony An Educational Resource from the New York State Archives Compelling Question: How do people succeed in a new place or environment? Courtesy: Len Tantillo Bakers in the Colony Objective: Describe the purpose of bakers in the colony and explain how bakers contributed to daily life in the colony. Essential Question: How did bakers contribute to the growth and success of the colony? Historical Background: Bread was the main staple of the Dutch diet both in the Netherlands and in the colony of New Netherland. Residents of the colony ate at least three times a day and bread was a key part of every meal. Bread in New Netherland was made mostly from wheat which could be grown in abundance in this part of the world. Bakers baked both rye and wheat bread. White bread was the most desirable bread and therefore was consumed mainly by the wealthier residents of the colony. Baking was a labor-intensive process that required significant amounts of time. The ovens were built with large bricks designed to stay hot for long periods of time. First, the baker would heat the oven with wood and clean out the residue when the oven was hot enough. Then the oven would be wiped clean with a wet cloth attached to the end of a stick. The baker had to knead the dough by hand or foot. Rye bread had to bake for 12 hours, while wheat bread had to rise twice and bake for an hour. The baker would blow his horn when the bread was ready so that his customers would know they could now purchase the bread and other baked goods. -

Van Rensselaer Family

.^^yVk. 929.2 V35204S ': 1715769 ^ REYNOLDS HISTORICAL '^^ GENEALOGY COLLECTION X W ® "^ iiX-i|i '€ -^ # V^t;j^ .^P> 3^"^V # © *j^; '^) * ^ 1 '^x '^ I It • i^© O ajKp -^^^ .a||^ .v^^ ^^^ ^^ wMj^ %^ ^o "V ^W 'K w ^- *P ^ • ^ ALLEN -^ COUNTY PUBLIC LIBR, W:^ lllillllli 3 1833 01436 9166 f% ^' J\ ^' ^% ^" ^%V> jil^ V^^ -llr.^ ^%V A^ '^' W* ^"^ '^" ^ ^' ?^% # "^ iir ^M^ V- r^ %f-^ ^ w ^ '9'A JC 4^' ^ V^ fel^ W' -^3- '^ ^^-' ^ ^' ^^ w^ ^3^ iK^ •rHnviDJ, ^l/OL American Historical Magazine VOL 2 JANUARY. I907. NO. I ' THE VAN RENSSELAER FAMILY. BY W. W. SPOONER. the early Dutch colonial families the Van OF Rensselaers were the first to acquire a great landed estate in America under the "patroon" system; they were among the first, after the English conquest of New Netherland, to have their possessions erected into a "manor," antedating the Livingstons and Van Cortlandts in this particular; and they were the last to relinquish their ancient prescriptive rights and to part with their hereditary demesnes under the altered social and political conditions of modem times. So far as an aristocracy, in the strict understanding of the term, may be said to have existed under American institu- tions—and it is an undoubted historical fact that a quite formal aristocratic society obtained throughout the colonial period and for some time subsequently, especially in New York, — the Van Rensselaers represented alike its highest attained privileges, its most elevated organization, and its most dignified expression. They were, in the first place, nobles in the old country, which cannot be said of any of the other manorial families of New York, although several of these claimed gentle descent. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

Ulster County Office for the Aging

Ulster County Office for the Aging July 2016 Newsletter Greetings from County Executive Michael P. Hein Tune in to Healthy Ulster Radio I am pleased to let you know that on June 26, 2016, Ulster County began a new weekly `Healthy Ulster Radio´ program designed to advance our goal of making Ulster County the healthiest county in New York State. `Healthy Ulster Radio´ will be co-hosted by Ulster County Commissioner of Health and Mental Health, Dr. Carol Smith and Vincent Martello, Director of Community Health Relations of the Ulster County Department of Health and Mental Health. The program will air on Pamal Broadcasting’s Kingston based stations, WBPM (92.9 FM) at 7:30 a.m. and WGHQ (920 AM), WLNA (1420 AM) and WBNR (1260 AM) at 8:30 a.m. The weekly program will explore community health and sustainability with guests representing a broad spectrum of community partners and sectors working to make Ulster County the healthiest county in New York State. In addition, Office for the Aging Director Kelly McMullen can be heard on radio station WGHQ (920 AM) the second Tuesday of every month. She is able to provide Senior Citizens with important information, special events, and current programs. There are many great things happening in Ulster County so I invite you to turn on your radio and tune in so you don’t miss a thing. Have a fun and safe summer! Mike Hein County Executive Ulster County Office for the Aging LUNCH AND LEARN Thursday, July 14th at Noon BRC, 1 Development Ct, Kingston, Room 114 When is it Time to Downsizing? How to declutter your home and make it safer Presented by Colleen Mountford of Next Step Home FREE LUNCH FOR ULSTER COUNTY SENIORS who RSVP Call OFA to RSVP 845-340-3456 Space is limited Michael P. -

1 the Beginnings

1 The Beginnings Here there bee not many people. —RoseRT JUST The geographical area of the original Diocese of New York was the entire state. It was not until 1838, and then only after profound misgiv- ings, that the laws of the Episcopal Church were altered to permit the subdivision of dioceses within the state. Thus, the Diocese of New York was all that territory from Long Island's wave-washed tip to Niagara's steady roar. Within this vast space lay the Adirondack Mountains, whose forests sloped northward to the St. Lawrence plains. Further west were the high fields surrounding the Finger Lakes, where the curved horizon makes a man know that he truly inhabits a spherical earth. Below these lakes is the Southern Tier, lonely and grim-gray In winter, benign and balmy in summer. The state diocese knew all the moods and variations of nature. No citizen of the new nation would know them better than Hobart and Onderdonk, the much-traveled third and fourth bishops of the Diocese of New York. Their predecessors, Samuel Provoost and Benjamin Moore, never saw the broad varieties of New York. They were town men, born and bred in Manhattan. It is one of the ironies of history that these men, the first bishops of the diocese, conceived their diocese more nearly as we do today: a jurisdiction flowing from the City of New York, dependent upon the metropolis, yet offering it the gifts and produce a city always requires from its rural surroundings. The men and women who perceived the early fortunes of the Dio- cese of New York may have seen the state as a builder's square. -

Federal Communications Commission Record 9 FCC Red No

FCC 94-85 Federal Communications Commission Record 9 FCC Red No. 10 MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Before the AND NOTICE OF APPARENT LIABILITY Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 Adopted: April 11, 1994; Released: April 28, 1994 In re Applications of By the Commission: Beacon File Nos. BR-910125UZ Broadcasting BRH-910125VG I. INTRODUCTION Corporation 1. The Commission has before it for consideration: (i) license renewal applications for the eight captioned radio stations in New York; (ii) a Petition to Deny timely filed For Renewal of Licenses of by the New York State Conference of Branches of the Station WBNR(AM) National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo Beacon, New York ple (NAACP) and various local NAACP branches in New and York against the above-captioned renewal applications;2 Station WSPK(FM) (iii) oppositions from the licensees; and (iv) the licensees© responses to staff letters of inquiry. The NAACP alleges Poughkeepsie, New York that the above stations violated the Commission©s equal employment opportunity (EEO) Rule and policies toward Culver File No. BR-910125UX minorities. The petitioner requests that the Commission Communications designate the licensees© renewal applications for hearing Corp., Inc. and deny the applications. For Renewal of License of II. BACKGROUND Station WLVL(AM) 2. In challenging an application pursuant to Section Lockport, New York 309(d) of the Communications Act, a petitioner must dem onstrate party in interest status. In addition, a petitioner Great Lakes File No. BRH-9102010I must, as a threshold matter, submit "specific allegations of Wireless Talking fact sufficient to show... that a grant of the application Machine Company would be prima facie inconsistent with [the public interest, convenience, and necessity]." 47 U.S.C. -

PAMAL BROADCASTING, LTD EEO PUBLIC FILE January 22, 2018 to January 21, 2019

PAMAL BROADCASTING, LTD EEO PUBLIC FILE January 22, 2018 to January 21, 2019 WBNR, WHUD, WLNA, WSPK, WXPK WBPM, WGHQ The above stations are owned and operated by Pamal Broadcasting Ltd., and licensed to its subsidiary 6 Johnson Road Licenses, Inc. Pamal Broadcasting Ltd. is an equal opportunity employer that encourages minorities and females to apply for job openings. SECTION I. Vacancy List. The following chart shows the positions filled during the reporting period. Please see section II for the full Master Recruitment Source List for recruitment source data: Job Title Recruitment Sources RS Referring Hiree Notified of Vacancies WHUD Promotions 1,2, 3, 4, 5,6,8, 9, 13, 14, 2 Director 15,16,17,18, 20, 21, 22 White Plains Sales 1,2, 3, 4, 5,6,8, 10, 13, 6 Manager 14, 15,16,17, 18, 20, 21,22 Account Executive 1,2, 3, 4, 5,6,8,10, 11,13, Two hires from this 14, 15,16,17, 18, 20, search- 11 & 6 21,22 Sales Manager/Beacon 1,2, 3, 4, 5,6,8, 10, 3 Office 13,14, 15,16,17, 18, 20, 21, 22 Account Executive 1,2, 3, 4, 5,6, 8, 10, 3 11,12, 14, 15,16,17, 20, 21, 22 White Plains Sales 1,2, 3, 4, 5,6, 8, 9, 10, 6 Manager 12,14, 15,16,17, 20, 21,22 *Some recruiting sources requested to be notified during the reporting period. Other recruiting sources no longer wanted notifications of vacancies during the reporting period. All sources that requested to be notified of openings were notified during the time when they requested notifications.