Being Sent : a Personal Reflection on Jesuit Governance in Changing Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Is Jesus? What Theologians Are Saying About Christ

Sept. 17,America 2007 THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY $2.75 Who Is Jesus? What theologians are saying about Christ Alejandro Garcia-Rivera Kevin Burke Robert P. Imbelli John R. Donahue William Thompson- Uberuaga Robert Krieg OR THE BETTER PART of two weeks Working Among Jews and Muslims. last month, I found myself In New York, we were joined by both America engaged in ecumenical and inter- Jewish interlocutors and Catholic lay col- Published by Jesuits of the United States religious dialogue. At the leagues. Jewish contributors like Rabbi Editor in Chief FUniversity of Notre Dame, I participated Harold Hirsch from Regis University in in the fourth annual Mennonite-Catholic Denver and Professor Harold Kasimow Drew Christiansen, S.J. Theological Colloquium, where theolo- from Grinnell University in Iowa showed Acting Publisher gians from both communities evaluated enormous appreciation for the teaching Called Together to Be Peacemakers, the 2004 and initiatives of Pope John Paul II. One James Martin, S.J. report of the International Catholic- could sense as they spoke just how much Managing Editor Mennonite Dialogue. Theologians on John Paul’s commitment to Catholic- both sides explored how to build new Jewish relations had achieved. During a Robert C. Collins, S.J. bridges. Some pressed those responsible tour of Jewish New York, the hazan or Business Manager for the dialogue to move still further, cantor at the Portuguese Synagogue on Lisa Pope while others reminded everyone that some Central Park West, the oldest in the differences will not be easily overcome. United States, educated us not only on Editorial Director There was considerable disappoint- early American Jewish history but on the Karen Sue Smith ment on the Mennonite side that various liturgical styles of western Catholics have done relatively little to Sephardism, singing for us the very dif- Online Editor make Called Together better known. -

A Year of Prayer

A Year of Prayer October 2005 - May 2006 Gratitude Healing Call Co-Laboring Guide Book Explanation: Table of Contents The culminating exercise of the Spiritual Exercises is entitled, “The Contemplation to Attain Love.” In it Saint Ignatius asks to us reflect on “[H]ow God dwells in creatures... So He dwells in me and gives me being, life, sensa- tion, intelligence. ...[C]onsider how God works and labors for me..., how he conducts himself as one who labors.” Welcome — Fr. Tim Brown, S.J., Provincial ....................................................... 1 Earlier in the same Contemplation, Ignatius observed that love is shown not so much Suggestions for Using this Guide Book ............................................................. 3 in words, but in deeds, especially in mutual sharing. And it is in God’s giving in labor- Origin and Aim of the Spiritual Exercises .......................................................... 5 ing that we are invited to understand and respond to God. Ignatius’ Conversion Experience Drawing on the inspiration of the Spiritual Exercises, Decree 26 of General Congre- gation 34 builds on this insight and conviction, when it says: Summary View of the Spiritual Exercises The God of Ignatius is the God who is at work in all things: laboring for the sal- Prayer Forms in the Spiritual Exercises vation of all as in the Contemplation to Attain Love ... The Use of Repetition .............................................................................. 23 For a Jesuit, therefore, not just any response to the needs of the men and wom- The Influence of Images on Prayer ......................................................... 25 en of today will do. The initiative must come from the Lord laboring in events and people here and now. God invites us to join with him in his labors, on his Bartimaeus: a Role Model for Our Year of Prayer ............................................ -

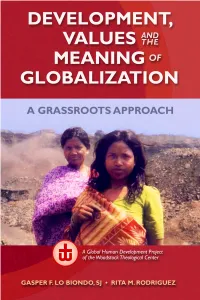

Development, Values, and the Meaning of Globalization: a Grassroots Approach

Development, Values, and the Meaning of Globalization: A Grassroots Approach Gasper F. Lo Biondo, SJ Rita M. Rodriguez Results of the Woodstock Theological Center’s Global Economy and Cultures Project In Collaboration with Jesuit Social Centers A free downloadable electronic version of this text is available online at: woodstock.georgetown.edu/gec THE WOODSTOCK THEOLOGICAL CENTER at Georgetown University • Washington, DC Copyright © 2012 Gasper F. Lo Biondo, SJ, and Rita M. Rodriguez Published in the United States of America by the Woodstock Theological Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Woodstock Theological Center Georgetown University, Box 571137 Washington, DC 20057-1137 [email protected] http://woodstock.georgetown.edu Book and eBook production manager: Matthew Gladden Cover photo: Shanti and Manjhu, in front of the coal mine encroaching on their village in Agaria Tola, Jharkhand, India; photo courtesy of Tony Herbert, SJ. Cover design by Keelan Downton and Matthew Gladden Photos from the Global Economy and Cultures project’s International Consultations and of the narrative mosaic tiles were provided by Woodstock Theological Center staff; photos of the narrative protagonists in their home towns were provided courtesy of Tony Herbert, SJ (Chapters 5-6); Leonard Chiti, SJ (Chapter 7); Josep Mària, SJ (Chapter 8); David Velasco Yáñez, SJ (Chapter 9); Rev. Tianzhi Peter Chen (Chapter 10); Bernard Lestienne, SJ (Chapter 11); AXJ Bosco, SJ (Chapter 12); Robin Schweiger, SJ (Chapter 13); Chong-Dae Kim, SJ (Chapter 14); and Rev. -

OSJ Archival Library List

OSJ Archival Library List The following books are available for research and study and can only be used under supervision. Please call 215-923-1733 for an appointment. ART, MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE: VARIA TITLE AUTHOR A Gallery collects Peales Schwarz ,Robert Devlin American Country Furniture: 1780-1875 Kovel, Ralph & Terry Benjamin West: Biography Alberts, Robert Catalog: Historical Bldgs,Sites&Remains in Penna Joint State Gov. Commission Catholic Church Hymnal with Music Tozer,A.Edmonds,Edited Church Organs Ogasapian, John K Colonial Houses:Phila. Pre Revolutionary Period Wallace,Phillip B. Historical Sacred Places of Phila. Moss, Roger W. History of English Organs Bickrell, Stephen In Pursuit of Fame: Rembrandt Peale 1778-1860 Miller, Lillan B. John Peale II, A Pictorial Biography Hebblethwaite, Peter&Kaufman,Ludwig Landmarking: City,Church&Jesuit Urban Stategy Lucas,Thomas M.,SJ Old Phila.Houses on Society Hill 1750-1840 McCall, Eliz. G. Painted Prayers: the Bk of Hrs in Medieval and Renaissance Art Wieck, Roger S. People’s Mass Book People’s Mass Book Committee Peter Paul Ruebens Coffey,Susan C., Research Curator Philadelphia Discovered Burt,Nathaniel, Editor Pope John Paul II: Building up the Body of Christ Nat’l Cath.News Service Pugin, Augustus Welby Pevsner,Nicholas (Preface) Rembrandt Peale: A Life of Arts, 1778-1860 Hevner, Carol Eaton Stained Glass in Catholic Phila. Fransworth,Jean M., Croce, Carmen Corce The Beginnings of Phila.: 1857-1957 Lithographs The Ceiling Paintings for Jesuit Chaped(Antwerp) Martin,John Rupert The Jesuits and the Arts, 1540-1773 Ed: John O’Malley, SJ The Lure of Italy: Amer Artisits&Italian Experience(1760-1914) Stebbins, Theodore E. -

Spiritual Leaders in the IFOR Peace Movement Part 1

A Lexicon of Spiritual Leaders In the IFOR Peace Movement Part 1 Version 3 Page 1 of 52 2010 Dave D’Albert Argentina ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Adolfo Pérez Esquivel 1931- .......................................................................................................... 3 Australia/New Zealand ........................................................................................................................ 4 E. P. Blamires 1878-1967 ............................................................................................................... 4 Austria ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kaspar Mayr 1891-1963 .................................................................................................................. 5 Hildegard Goss-Mayr 1930- ............................................................................................................ 6 Belgium ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Jean van Lierde ............................................................................................................................... 8 Czech ................................................................................................................................................. -

Dear Mister President Advice for Barack Obama of MANY THINGS PUBLISHED by JESUITS of the UNITED STATES

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY JAN. 19–26, 2009 $2.75 Dear Mister President Advice for Barack Obama OF MANY THINGS PUBLISHED BY JESUITS OF THE UNITED STATES napshots of family and friends Pauline Belt, an African-American res- EDITOR IN CHIEF taken over the decades, some ident at Sursum Corda, seated in the Drew Christiansen, S.J. dating back to the 1960s, lie in church’s little social hall. S EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT small packets in my desk drawer. From The photo is in a glass display case time to time I take them from their there, near a hand-drawn crayon pic- MANAGING EDITOR envelope to look again at those familiar ture of Horace done by one of the Robert C. Collins, S.J. faces. Most are smiling, and you can homeless men he served. Pauline was EDITORIAL DIRECTOR almost hear them responding to the old then, and now is with God. Karen Sue Smith command, “Say cheese!” About half, Sursum Corda, designed as a model ONLINE EDITOR though, are no longer physically pre- inner-city village with trees, open Maurice Timothy Reidy sent in this world, and so I like to see spaces and units with five bedrooms CULTURE EDITOR them in my mind’s eye as smiling in the for large families, is facing its own James Martin, S.J. presence of the God who has received death as real estate developers close in LITERARY EDITOR them. with plans that have already displaced Patricia A. Kossmann Among the oldest of the snapshots many low-income residents. POETRY EDITOR are two of my parents, taken when Other social hall snapshots show James S. -

Service to the Universal Church

MARYLAND • NEW ENGLAND • NEW YORK PROVINCES SUMMER 2011 Service to the Universal Church Service to the Universal Church SOCIETY OF JESUS V. Rev. James M. Shea, SJ V. Rev. Myles N. Sheehan, SJ V. Rev. David S. Ciancimino, SJ Provincial of Maryland Provincial of New England Provincial of New York Our Mission Deepening our Commitment to the Church We seek to respond to the We were honored to have the Very Rev. Adolfo Nicolás, our Jesuit Superior General, ever-present invitation attend the meeting of the Jesuit provincials of the United States this February in of the Society and our Kingston, Jamaica. The provincials had gathered for their meeting of the U.S. Jesuit tradition to keep the goal Conference Board, which occurs three times a year. Also in attendance was the of our Society before our provincial of English-speaking Canada, Fr. Jim Webb, SJ. Fr. General took part in eyes and to look for the the plenary meetings and met individually with each provincial. He then spent the best instruments that will rest of his time in Kingston visiting the Jesuit communities and works of Jamaica, allow us to discern the a dependent region of the New England Province. will of God and respond Fr. General encouraged the provincials to move forward with the work of the 35th generously and effectively General Congregation. He spoke eloquently about a favorite theme of his — the depth to Christ’s call to serve that should pervade our Jesuit ministry, our theology, our work in education, anywhere with Him in our world of a Jesuit is missioned. -

The Jesuit Ministry of Reconciliation

So We Are Ambassadors for Christ The Jesuit Ministry of Reconciliation WILLIAM C. WOODY, S.J. 49/1 SPRING 2017 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Guy Consolmagno, SJ, is director of the Vatican Observatory, Rome. (2014) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he teaches and writes on Jesuit Spirituality at Regis University in Denver, Colorado. (2013) Michael Harter, SJ, is assistant for formation for the US Central and Southern Province, St. Louis, Missouri. (2014) , teaches Spanish Literature and directs the Graduate Program in Modern Languages and Literatures at Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. (2015) Michael Knox, SJ, is director of the Shrine of the Jesuit Martyrs of Canada in Midland, Ontario, and lecturer at Regis College in Toronto. (2016) Hung Pham, SJ, teaches spirituality at the Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, California. -

Ramview + Ann. Report 2005

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Vol. 30 — No. 1 Fall 2009 RaRA PUBLICATIOaN FOR THmvim E ALUMNI, PAREviNTS AND FRIEeeNDS OF w Fw ORDHAM PREP CAPITAL CAMPAIGN HONOR ROLL Gifts & Pledges To Date: June 30, 2009 $19.9 Million Anonymous Mr. & Mrs. William D. Anderson, Jr. P ’12 The Estate of Cecelia Augustine Mr. Robert W. Bertrand ’58 The Estate of Myrtle K. Brennan Mr. & Mrs. Timothy J. Brosnan ’76 Mr. John D. Brusco ’83 Mr. & Mrs. Joseph O. Brusco ’08 Mr. & Mrs. Nicholas E. Brusco ’79 Mr. & Mrs. Nicola Brusco P ’83 Mr. Paul A. Brusco ’82 Mr. Thomas J. Campbell ’76 Mr. Francis X. Coleman, Jr. ’49 * Mr. Maurice J. Cunniffe ’50 Bernard J. Daenzer, Esq. ’34 Drs. Vincent & Anna DiCicco P ’12 Mr. & Mrs. Thomas V. Dolan ’78 $9.6 Million Expansion and Mr. Patrick J. Dooley ’80 The Estate of Edward J. Driscoll ’47 The Estate of David V. Duchini ’41 Renovation Project Completed Mr. & Mrs. John Duffy P ’99 Mr. Dennis J. FitzSimons ’67 Donors Who Made It Possible Honored at Dinner on October 2nd The Estate of Richard Flood ’51 (Photographs & Details available at www.fordhamprepconnect.org) Mr. Edward L. Flynn ’53 Mr. Robert P. Ford ’87 By Greg Curran, Chairman of the Science Department & Director of Technology Mr. & Mrs. Paul M. Frank ’56 Mr. Mario J. Gabelli ’61 Days after graduation in June of 2008, construction began on a project that would add a fourth floor to the Prep’s Mr. John M. Geraghty ’60 main building and renovate a large portion of the school’s third floor complement of classrooms and laboratories. -

Horace PRIEST of the POOR

Horace PRIEST OF THE POOR Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown HORACE B. McKENNA, SJ. APRIL 6, 1982 Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown HORACE PRIEST OF THE POOR John S. Monagan GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY PRESS Washington, D.C. Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown 788455 iEOBGETOWU UNIVEBSI3C2 LIBRARIES MAY 27 1886 COPYRIGHT© 1985 BY JOHN S. MONAGAN All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Monagan, John S. Horace, priest of the poor. Includes index. 1. McKenna, Horace Bernard, 1899-1982. 2. Catholic Church—United States—Clergy—Biography. 3. Poor— United States. I. Title. BX4705.M4765M66 1985 282'.092'4 [B] 85-10042 ISBN0-87840-421-X PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Book design by Stella D. Matalas Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown To Rosemary and our children Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown With deep appreciation to Ann O'Donnell and R. Emmett Curran, S.J., for their encouragement and support. A tip of the hat to Robert O'Brien and John B. Breslin, S.J., for their inspiration and advice. And a bow to Evelyn Bence, Deborah McCann, and Eleanor Waters for their editorial and production know-how that helped turn a manuscript into a book. Warmest thanks also to those who cheerfully and even eagerly talked to me about Horace and whose names appear throughout this book. A natural question arises as to the propriety of using Horace's given name throughout this study. -

WELCOMING TOM CHABOLLA a New Leader Takes the Helm of JVC This November // JVC Makes Key Changes Across Its Formation and Support Programs

Fall 2018 NEWS FOR FORMER, CURRENT, AND FUTURE JESUIT VOLUNTEERS AND SUPPORTERS WELCOMING TOM CHABOLLA A new leader takes the helm of JVC this November // JVC makes key changes across its formation and support programs // Former Jesuit Volunteers answer the call to work for justice BOARD OF DIRECTORS † FORMER JESUIT VOLUNTEER Table of Contents * JESUIT EDUCATED Introducing Tom Chabolla...................................................................................... Joan Hogan Gillman * 4 Chair A new president takes the helm of JVC on November 1 Fr. Fred Kammer, SJ * Vice Chair JVC Hosts its Inaugural One Orientation ............................................................ 6 An integrated orientation brings all Jesuit Volunteers together for the first time in Fr. Michael McFarland, SJ * the organization’s history Treasurer Finance Chair In-City Coordinators Provide Unprecedented Support to Volunteers ............ 9 John Carron †* JVC implements a new model of local support to facilitate the volunteer experience Secretary Mary Berner * Local Orientation: Cleveland’s JVs Explore Ohio’s North Coast .................. 10 Audit Chair Abe Grindle †* In the Field............................................................................................................. 14 Program Chair Tacna JVs lead a grueling mission trip in the mountains of Peru Fr. Vin DeCola, SJ * Development Chair Agency Feature: Nashville’s Project Return .................................................... 16 Jack McLean * Governance Chair JVC Pilots an Updated -

SUMMER Ramview 2017-Updated

Ramview SUMMER 2017 President’s Message .................4 Principal’s Message ..................5 Admissions ..........................6 College Destinations .................7 School Events Recap .................8 Athletics ...........................15 Feature: Continuing the Legacy .......22 175 Things about Fordham Prep ...... 27 Around the Prep ....................43 Engagement & Development . ........47 Reunion 2017 .......................50 Mission & Identity ...................54 Class Notes ........................56 Births, Weddings, In Memoriam ......59 Farewells ...........................60 FP Archives . ........................61 Hall of Honor Inductees ..............63 Letters to the editor and all correspondence should be sent to [email protected]. The Rugby team visited London during this year’s Easter recess. every Ivy League university and every service academy, as well as premiere Catholic, Jesuit, private and public institutions. • Service to the community: During their senior year alone, our students perform 17,000 hours of Christian service in community-based organizations throughout the metropolitan area. • Improvements in campus facilities: This summer, we are investing more than $1 million in the construction of a new chapel, a new sound system for the Leonard Theatre, faculty offices, group study rooms, a technology office suite, and classroom and locker room renovations. Our future plans call for a dramatic expansion of the building’s east wing to develop larger classrooms and a new counseling suite. • Global education and cultural competence: Through our global Jesuit educational network, this summer students are participating in academic, service-learning and cultural immersion programs in Australia, China, Ecuador, Tennessee and Camden, NJ. Last year, students studied marine biology in Belize and classical languages in Rome. In the next two years, they will study at Jesuit high schools in Ireland, Uruguay, Rwanda and Tanzania.