The Commodity Price Boom and Regional Workers in Chile: a Natural Resources Blessing?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SURNAMES in CHILE a Study of the Population of Chile Through

Page 1 of 31 American Journal of Physical Anthropology 1 2 3 SURNAMES IN CHILE 4 5 A study of the population of Chile through isonymy 6 I. Barrai, A. Rodriguez-Larralde 2, J. Dipierri 1, E.Alfaro 1, N. Acevedo 3, 7 8 E. Mamolini, M. Sandri, A.Carrieri and C. Scapoli. 9 10 Dipartimento di Biologia ed Evoluzione, Università di Ferrara, 44121- Ferrara, Italy 11 1Instituto de Biología de la Altura, Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, 4600 – San Salvador De Jujuy, 12 13 Argentina. 14 2 15 Centro de Medicina Experimental, Laboratorio de Genetica Humana, IVIC, 1020A -Caracas, 16 Venezuela. 17 18 3Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Santiago, Chile 19 20 21 Running title: Surnames in Chile 22 23 24 25 26 Correspondence to: 27 Chiara Scapoli 28 Department of Biology and Evolution 29 30 University of Ferrara, 31 Via L. Borsari 46, - I-44121 Ferrara, Italy. 32 Telephone: +39 0532 455744; FAX: : +39 0532 249761 33 Email: [email protected] 34 35 36 Number of text pages: 15 37 Literature pages: 4 38 39 Number of Tables : 2 40 41 Number of Figures: 7 42 43 44 KEYWORDS : Chile, Population Structure, Isonymy, Inbreeding, Isolation by distance 45 46 47 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors are grateful to the Director of the Servicio Electoral de la 48 49 Republica de Chile Sr. Juan Ignacio Garcia Rodríguez, who made the data available, and to Sr. 50 51 Dr.Ginés Mario Gonzalez Garcia, Embajador de la Republica Argentina en Chile. The work was 52 supported by grants of the Italian Ministry of Universities and Research (MIUR) to Chiara Scapoli. -

Valparaiso.Pdf

REGION PROVINCIA COMUNA AREA LOCAL CENSAL DIRECCION NUMERO VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO ADULTO MAYOR AÑOS DORADOSPASAJE ALBERTO HURTADO 170 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO CENTRO DE REHABILITACIÓN RENACERAV. AGUAS MARINAS S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO CLUB DE ADULTO MAYOR DE ALGARROBOLOS CEREZOS 1080 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO COLEGIO CARLOS ALESSANDRI ALTAMIRANOEL OLMO 1599 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO JARDÍN INFANTIL MIRASOL AV. MIRASOL S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO JUNTA DE VECINOS 4-2 EL YECOLIBERTADORES - SEDE JUNTA DECON VECINOS ISABEL RIQUELMEEL YECO S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO JUNTA DE VECINOS LAS TINAJASYUCATÁN DEL CANELO 1535 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO MUNICIPALIDAD DE ALGARROBOCARLOS - CASA ALESSANDRI DE LA CULTURA 1633 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO MUNICIPALIDAD DE ALGARROBOAV. - OFICINAPEÑABLANCA PRINCIPAL 250, ALGARROBO REGIÓN:V 250VALPARAÍSO VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO RURAL COLEGIO PUKALAN DE ALGARROBOCAMINO EL TOTORAL ESQUINA 12 DE LA FAMA 12S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA RURAL SAN JOSEKILOMETRO 20 CAMINO LAS DICHAS S/N SN VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO RURAL ESCUELA PARTICULAR SAN JOSECAMINO MIRASOL KM 21 S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO ESCUELA BASICA VALLE DE ARTIFICIOCALLE MANUEL MONTT S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO ESCUELA HANS WENKE MENGERSPOBLACIÓN CERRO NEGRO PASAJE LA QUINTRALA560 VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO LICEO BICENTENARIO TECNICO AVDA.PROFESIONAL HUMERES DE MINERIA 1510 VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO LICEO Y ESCUELA MUNICIPAL ZOILA GAC 639 VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA G-45 CAMINO A ALICAHUE KM. 13 LA VEGA S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA G-47 GUAYACAN, CAMINO A CERRO NEGRO S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA LA FRONTERA CASASDE ALICAHUE ALICAHUE KM. -

MATRIZ SUCURSAL COMUNA.Xlsx

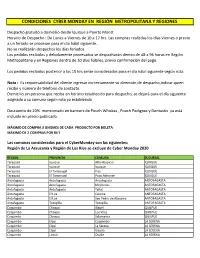

CONDICIONES CYBER MONDAY EN REGIÓN METROPOLITANA Y REGIONES Despacho gratuito a domicilio desde Iquique a Puerto Montt Horario de Despacho : De Lunes a Viernes de 10 a 17 hrs. Las compras realizdas los días Viernes o previo a un feriado se procesan para el día hábil siguiente. No se realizarán despachos los días feriados. Los pedidos recibidos y debidamente procesados se despacharán dentro de 48 a 96 horas en Región Metropolitana y en Regiones dentro de 10 días hábiles, previa confirmación del pago. Los pedidos recibidos posterior a las 15 hrs serán considerados para el día hábil siguiente según ruta. Nota : Es responsabilidad del cliente ingresar correctamente su dirección de despacho,indicar quien recibe y número de telefóno de contacto. Domicilio sin persona que reciba en horario establecido para despacho, se dejará para el día siguiente asignado a su comuna según ruta ya establecida. Descuento de 20% mencionado en banners de Pouch Whiskas , Pouch Pedigree y Dentastix ya está incluido en precio publicado. MÁXIMO DE COMPRA 3 UNIDAES DE CADA PRODUCTO POR BOLETA MÁXIMO DE 2 COMPRAS POR RUT Las comunas consideradas para el CyberMonday son las siguientes: Región de La Araucania y Región de Los Rios se excluye de Cyber Monday 2020 REGION PROVINCIA COMUNA SUCURSAL Tarapacá Iquique Alto Hospicio IQUIQUE Tarapacá Iquique Iquique IQUIQUE Tarapacá El Tamarugal Pica IQUIQUE Tarapacá El Tamarugal Pozo Almonte IQUIQUE Antofagasta Antofagasta Antofagasta ANTOFAGASTA Antofagasta Antofagasta Mejillones ANTOFAGASTA Antofagasta Antofagasta Taltal ANTOFAGASTA -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Cuenca Aconcagua

Cuenca Aconcagua INFORMACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA Código BNA 054 Región V Valparaíso Superficie Cuenca (km2) 7.334 Provincia (s) Comuna (s) - Quintero - Valparaíso - Concón - Villa Alemana - Marga Marga - Limache - Olmué - Quillota - Nogales - Quillota - Hijuelas - Calera - La Cruz - Llayllay - Panquehue - Catemu - San Felipe de Aconcagua - San Felipe - Putaendo - Santa María - San Esteban - Los Andes - Los Andes - Calle larga - Rinconada INFORMACIÓN HIDROLÓGICA El principal cauce es el río Aconcagua que tiene una extensión de 399.409 m, tiene un caudal medio Cauces Principales anual en la estación “Aconcagua en Chacabuquito” de 33,1 m3/s. El río Aconcagua recibe aportes en su trayecto de los ríos Colorado y Putaendo La cuenca posee una gran cantidad de lagunas en la parte alta, siendo la más importante la Laguna Lagos del Inca que tiene una superficie de 1,7 km2. Existen aproximadamente 15 embalses en la cuenca, sin embargo, el de mayor tamaño es el Embalses Embalse Los Aromos que tiene una superficie de 2,1 km2 y una capacidad de 35 Millones de m3 y su uso es de agua potable. Actualmente tiene un volumen almacenado de 15,5 Mm3. INFORMACIÓN HIDROGEOLÓGICA 1- San Felipe 2- Putaendo 3- Panquehue Acuífero de Aconcagua se divide en 9 SHAC 4- Catemu Acuíferos 5- Llay Llay 6- Nogales-Hijuelas 7- Quillota 8- Aconcagua desembocadura 9- Limache INFORMACIÓN HIDROMÉTRICA - Río Juncal en Juncal - Río Blanco en río Blanco En la cuenca hay 11 estaciones fluviométricas - Río Aconcagua en río Blanco Estaciones - Río Colorado en Colorado vigentes: - Río Aconcagua -

Gobernación Provincial San Felipe De Aconcagua

Gobernación Provincial San Felipe de Aconcagua I. Antecedentes provinciales La Gobernación Provincial de San Felipe de Aconcagua es un Servicio que depende del Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública que ejecuta su acción en las seis comunas de la Provincia de San Felipe. Su misión es asistir el ejercicio del Gobierno y la administración interior del Estado en la provincia, respecto de la Protección Civil, la Seguridad Pública y la coordinación para un eficiente desempeño de los Servicios Públicos en beneficio directo de toda la ciudadanía. La Provincia de San Felipe está compuesta por las comunas de Llay Llay, Catemu, Panquehue, Putaendo, Santa María y San Felipe. Tiene una extensión de 2 mil 659 kilómetros cuadrados y una población de 154 mil 718 habitantes. II. Principales logros alcanzados durante el 2020 1. Departamento Social a) Fondo ORASMI: El Departamento Social de la Gobernación de San Felipe durante el año 2020, por intermedio del programa Fondo ORASMI, entregó beneficios a 161 usuarios/as de la provincia, con una inversión de $33.764.440. Porcentaje de personas Beneficiadas por comuna Año 2020 2 7 3 7 7 74 San Felipe Catemu Llay-Llay Panquehue Putaendo Santa María El Fondo ORASMI es una herramienta para la gestión del Gobierno Provincial, cuyo fin es “contribuir a disminuir las situaciones de vulnerabilidad transitoria que se dan por la incapacidad de las personas y familias de asumir los costos económicos de ciertas situaciones del entorno, fortaleciendo así la cobertura de la acción social del Estado”. De acuerdo a lo anterior, su propósito es: “que las personas y sus familias cuenten con respuestas económicas en complementariedad con otras instituciones y recursos propios para enfrentar situaciones que los expongan a un estado de vulnerabilidad transitoria”. -

Cuenca Del Rio Aconcagua

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE AGUAS DIAGNOSTICO Y CLASIFICACION DE LOS CURSOS Y CUERPOS DE AGUA SEGUN OBJETIVOS DE CALIDAD CUENCA DEL RIO ACONCAGUA DICIEMBRE 2004 Aconcagua i. I N D I C E ITEM DESCRIPCION PAGINA 1. ELECCION DE LA CUENCA Y DEFINICION DE CAUCES ........................1 2. RECOPILACION DE INFORMACION Y CARACTERIZACION DE LA CUENCA.............................................................................................................4 2.1 Cartografía y Segmentación Preliminar ..............................................................4 2.2 Sistema Físico Natural.........................................................................................6 2.2.1 Clima ...................................................................................................................6 2.2.2 Geología y volcanismo ........................................................................................8 2.2.3 Hidrogeología ......................................................................................................8 2.2.4 Geomorfología...................................................................................................11 2.2.5 Suelos ................................................................................................................12 2.3 Flora y Fauna de la Cuenca del Río Aconcagua................................................13 2.3.1 Flora terrestre y acuática ...................................................................................13 2.3.2 Fauna acuática ...................................................................................................15 -

Identifying Hotspots of Cardiometabolic Outcomes Based on a Bayesian Approach: the Example of Chile

PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Identifying hotspots of cardiometabolic outcomes based on a Bayesian approach: The example of Chile 1 2 1 3 Gloria A. AguayoID *, Anna Schritz , Maria Ruiz-Castell , Luis Villarroel , 3 1 4,5 6 Gonzalo Valdivia , Guy FagherazziID , Daniel R. WitteID , Andrew Lawson 1 Population Health Department, Luxembourg Institute of Health, Strassen, Luxembourg, 2 Competence Center for Methodology and Statistics, Luxembourg Institute of Health, Strassen, Luxembourg, 3 Department of Public Health, School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad CatoÂlica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 4 Department of Public Health, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark, 5 Danish Diabetes Academy, Odense, Denmark, a1111111111 6 Department of Public Health Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, South Carolina, Charleston, a1111111111 United States of America a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract OPEN ACCESS Background Citation: Aguayo GA, Schritz A, Ruiz-Castell M, There is a need to identify priority zones for cardiometabolic prevention. Disease mapping in Villarroel L, Valdivia G, Fagherazzi G, et al. (2020) countries with high heterogeneity in the geographic distribution of the population is challeng- Identifying hotspots of cardiometabolic outcomes based on a Bayesian approach: The example of ing. Our goal was to map the cardiometabolic health and identify hotspots of disease using Chile. PLoS ONE 15(6): e0235009. https://doi.org/ data from a national health survey. 10.1371/journal.pone.0235009 Editor: Nayu Ikeda, National Institute of Health and Methods Nutrition, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition, JAPAN Using Chile as a case study, we applied a Bayesian hierarchical modelling. We performed a Received: December 10, 2019 cross-sectional analysis of the 2009±2010 Chilean Health Survey. -

Centro De Salud Familar

Municipalidad de Hijuelas Departamento de Salud CESFAM Hijuelas DEPARTAMENTO DE SALUD CENTRO DE SALUD FAMILAR Municipalidad de Hijuelas CENTRO DE SALUD FAMILIAR Departamento De Salud /Municipalidad de Hijuelas _____________________________________________________________________________________ ÍNDICE TEMAS PÁGINA Índice.……………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………...1 -Comisión Plan Comunal de Salud y ejecutores………………………...........................................3 -Introducción………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………5 -Visión y Misión……………………………………………………….........................................................6 -Estructura Organizacional Dirección Comunal de Salud………………...................................7 -Logros Año 2005-2011…………………………………………………………………………………………….……9 Sección 1…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10 -Descripción de la comuna………………………………………………………………………………………………11 -Mapa……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 -Autoridades……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………14 -Datos del Departamentos………………………………………………………………………………………………15 -Población……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….16 -Características socioeconómicas-demográficas…………………………………………………………….17 -Grupos Vulnerables………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 -IDH dentro del territorio del SSVQ………………………………………………………………………………..24 -Estadísticas vitales…………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 Sección 2………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..26 -Diagnóstico participativo……………………………………………………………………………………………….27 -Metodología………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….27 -

En Valparaíso, a Veintinueve De Noviembre De Dos Mil Dieciséis

TRIBUNAL ELECTORAL REGIONAL V REGION VALPARAIS O ACTA DE ESCRUTINIO ELECCIONES MUNICIPALES 2016 PROVINCIA DE SAN FELIPE DE ACONCAGUA En Valparaíso, a veintinueve de noviembre de dos mil dieciséis, conforme establece el artículo 100 y siguientes de la ley N° 18.700, Orgánica Constitucional sobre Votaciones Populares y Escrutinios en relación con el artículo 119 de la Ley 18.695, Orgánica Constitucional de Municipalidades, se procede al escrutinio de la elección de Alcalde y Concejales celebrada el 23 de octubre último correspondientes a la Provincia de San Felipe de Aconcagua, integrada por las comunas de Catemu, Llay Llay, Panquehue, Putaendo, Santa María y San Felipe, ante la Presidenta doña Teresa Carolina Figueroa Chandía y Miembro titular, don Carlos Oliver Cadenas y Miembro suplente doña Gloria Toril Ivanovich. Actúa como ministro de fe el Secretario Relator don Andrés Torres Campbell. Incorporadas al sistema computacional del Tribunal todas las resoluciones derivadas del proceso de calificación, se procedió a practicar el escrutinio general de las elecciones de alcalde y concejales de las comunas que componen la Provincia de San Felipe de Aconcagua, de acuerdo al artículo 103 de la ley N° 18.700, Orgánica Constitucional sobre Votaciones Populares y Escrutinios. Para constancia, se levanta lapreena.- TERESA CAROLI1GUEROA CHANDIA ENTA OIL! VER CADENAS GLORIATOIRTII VANO VICH PRIMER MIEMBRO SEGUNDO MIEMBRO (S) ANSF S SECRETARIO Rl TOR Prat 732— 3er Piso - Valparaíso - Fonos: 322211014— 322232872— Fax: 322595291 www.ter5 .cl - [email protected] -

Chile Floods Shelters

MA013 Peru Pica Iquique Bolivia IQU IQU E TA R A PA C A Brazil TAM ARUGAL Pozo Almonte Paraguay Ollague B O L I V I A Chile Argentina Uruguay Tocopilla TOCOPILLA María Elena Calama EL LOA Antofagasta Mejillones Sierra Gorda Shelter Persons San Pedro de Atacama F-96 26 A N TO FA G A S TA Albergue Municipal 17 Junta de vecinos Gabriela Mistral 12 Total 55 Antofagasta Tal-Tal AN TOFAGASTA Shelter Persons Comedor Catolico 0 Diego De Almagro Junta de Vecinos N°3 25 Shelter Persons Food Parcels San Antonio Norte 45 Aliro Lamas Castillo 800 1200 Tal-Tal Total 70 Total 800 1200 Chañaral Nombre Establecimiento Alojados Alimentados Copiapo Shelter Persons Food Parcels Liceo Federico Varela 118 191 Diego de Almagro CHAÑAR AL Escuela Libertador Bernardo O"Higgins 176 200 Albergue Improvisado En Cerro 530 530 Chañaral Albergue Casino Enami 300 550 Escuela Vicente Sepulveda Rojo 17 30 Escuela Pedro Lujan 500 ~ Escuela Hernan Marquez Huerta 203 500 Totals 1448 1271 Escuela Fundicion Paipote 320 370 Caldera Escuela San Pedro 47 150 Caldera Copiapo Escuela Manuel Rodriguez 29 100 ATA C A M A Shelter Persons COPIAPO Escuela "El Chañar" 81 120 Escuela Manuel Blanco Encalada 177 Tierra Amarrilla Escuela El Palomar 58 300 Total 177 Escuela Luis Cruz Martínez 5 ~ Colegio Estacion 30 80 Tierra Amarilla Escuela F-41 82 ~ Shelter Persons Escuela F-42 90 ~ Escuela F-40 90 Total 1138 1850 Escuela D-43 27 VallenarHUASCO Escuala San Antonio 735 Freirina Alto del Carmen Escual Eduardo Campillay 100 Alto Del Carmen Total 952 La Higuera Name of Shelter Persons Food -

Región De Valparaíso

Región de Valparaíso Información regional 2014 Contenidos Región de Valparaíso 1 Mapa de la Región 2 Economía Regional 3 Aspectos Geográficos y Demográficos 3 Perfil de los Productores 4 Cultivos 7 Ganadería 8 Comercio Exterior 9 Riego 10 División Político-Administrativa 11 Antecedentes Sociales Regionales 14 Autoridades Región de Valparaíso 1 Mapa de la región Región de Valparaíso les a n r e d e P o í R Río del Sobrante a orc Pet Río Petorca e ahu Alic ero Est a a igu rc L to La e o P Rí ío R Río La Ligu a La Ligua Cabildo Papudo Zapallar Putaendo Nogales San Felipe ua ag Santa María Puchuncaví nc Catemu co La Calera A ío R Quintero Panquehue San Esteban Hijuelas La Cruz Rinconada Los Andes Llayllay Calle Larga Quillota San Félix Concón San Ambrosio Salas y Gómez Limache Viña del Mar Olmué Isla de Pascua VALPARAISO Villa Alemana Quilpué Casablanca Algarrobo El Quisco El Tabo SIMBOLOGÍA Archipiélago Juan Fernandez Ciudades y Centros Cartagena Urbanos San Antonio Costa, Cursos de Agua Rocas de Límite Comunal Santo Domingo Límite Provincial Límite Regional Río Maipo Límite Internacional Caminos Principales 0 10 20 40 60 80 Kms Escala 1:1.000.000 Región de Valparaíso 2 Economía regional Con respecto al año 2012, en 2013 la región aumentó su PIB en 3,6%, lo que equivale a un total de $8.461.149 millones de pesos. Esta cifra representa el 7,4% del PIB nacional. Cabe señalar, que en el año 2013, la región registró el tercer mayor PIB en comparación con el resto de las regiones del país.