The-Companion-Guide-V1-D2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Financial Statements for the Financial Year 2020/2021

GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/2021 Cmd. 10 of 2021 ________________ Presented to Parliament by Command of The President of the Republic of Singapore. Ordered by Parliament to lie upon the Table: 28/07/2021 ________________ GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR by OW FOOK CHUEN 2020/2021 Accountant-General, Singapore Copyright © 2021, Accountant-General's Department Mr Lawrence Wong Minister for Finance Singapore In compliance with Regulation 28 of the Financial Regulations (Cap. 109, Rg 1, 1990 Revised Edition), I submit the attached Financial Statements required by section 18 of the Financial Procedure Act (Cap. 109, 2012 Revised Edition) for the financial year 2020/2021. OW FOOK CHUEN Accountant-General Singapore 22 June 2021 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF SINGAPORE Opinion The Financial Statements of the Government of Singapore for the financial year 2020/2021 set out on pages 1 to 278 have been examined and audited under my direction as required by section 8(1) of the Audit Act (Cap. 17, 1999 Revised Edition). In my opinion, the accompanying financial statements have been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with Article 147(5) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1999 Revised Edition) and the Financial Procedure Act (Cap. 109, 2012 Revised Edition). As disclosed in the Explanatory Notes to the Statement of Budget Outturn, the Statement of Budget Outturn, which reports on the budgetary performance of the Government, includes a Net Investment Returns Contribution. This contribution is the amount of investment returns which the Government has taken in for spending, in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore. -

World War Two Squad Makeup

World War Two Squad Makeup Troop Type Rank US Army Rifle Squad / US Army Ranger Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Scout x 2 Private Rifleman x 5 Private Automatic Rifleman Private Assistant Automatic Rifleman Private Automatic Rifle Ammo Carrier Private US Army Armored Rifle Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Rifleman x 9 Private Driver Private US Army Heavy Machine Gun Squad Squad Leader Sergeant Machine Gunner Corporal Assistant Machine Gunner Private Machine Gun Ammo Carriers x 3 Private Driver Private US Army Light Machine Gun Squad Squad Leader Sergeant Machine Gunner Private Assistant Machine Gunner Private Machine Gun Ammo Carriers x 2 Private US Army Heavy Mortar Squad Squad Leader Staff Sergeant Mortar Gunner Corporal Assistant Mortar Gunner Private Mortar Ammo Carriers x 4 Private Driver Private US Army Light Mortar Squad Squad Leader Sergeant Mortar Gunner Private Assistant Mortar Gunner Private Mortar Ammo Carriers x 2 Private US Army Armored Anti Tank Squad Squad Leader Staff Sergeant Gunner Corporal Cannoneers x 4 Private Ammunition Carriers x 3 Private Driver Private US Army Airborne Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Scout x 2 Private Rifleman x 5 Private Machine Gunner Private Assistant Machine Gunner Private Machine Gun Ammo Carrier Private US Army Ranger Assault Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Rifleman x 5 Private -

International Military Cartridge Rifles and Bayonets

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY CARTRIDGE RIFLES AND BAYONETS The following table lists the most common international military rifles, their chambering, along with the most common bayonet types used with each. This list is not exhaustive, but is intended as a quick reference that covers the types most commonly encountered by today’s collectors. A Note Regarding Nomenclature: The blade configuration is listed, in parentheses, following the type. There is no precise dividing line between what blade length constitutes a knife bayonet vs. a sword bayonet. Blades 10-inches or shorter are typically considered knife bayonets. Blades over 12-inches are typically considered sword bayonets. Within the 10-12 inch range, terms are not consistently applied. For purposes of this chart, I have designated any blade over 12 inches as a sword bayonet. Country Rifle Cartridge Bayonet (type) Argentina M1879 Remington 11.15 x 58R Spanish M1879 (sword) Rolling-Block M1888 Commission 8 x 57 mm. M1871 (sword) Rifle M1871/84 (knife) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891 (sword) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. None Cavalry Carbine M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891/22 (knife) Engineer Carbine [modified M1879] M1891/22 (knife) [new made] M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 First Pattern (sword) M1909 Second Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 Second Cavalry Carbine Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) FN Model 1949 7.65 x 53 mm. FN Model 1949 (knife) FN-FAL 7.62 mm. NATO FAL Type A (knife) FAL Type C (socket) © Ralph E. Cobb 2007 all rights reserved Rev. -

The Changi Chapel and Museum 85

LOCALIZING MEMORYSCAPES, BUILDING A NATION: COMMEMORATING THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN SINGAPORE HAMZAH BIN MUZAINI NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 LOCALIZING MEMORYSCAPES, BUILDING A NATION: COMMEMORATING THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN SINGAPORE HAMZAH BIN MUZAINI B.A. (Hons), NUS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ‘Syukor Alhamdulillah!’ With the aid of the Almighty Allah, I have managed to accomplish the writing of this thesis. Thank god for the strength that has been bestowed upon me, without which this thesis might not have been possible indeed. A depth of gratitude to A/P Brenda Yeoh and A/P Peggy Teo, without whose guidance and supervision, I might not have been able to persevere with this endeavour. Thank you for your limitless patience and constant support throughout the two years. To A/P Brenda Yeoh especially: thanks for encouraging me to do this and also for going along with my “conference-going” frenzy! It made doing my Masters all that more exciting. A special shout-out to A. Jeyathurai, Simon Goh and all the others at the Singapore History Consultants and Changi Museum who introduced me to the amazing, amazing realm of Singapore’s history and the wonderful, wonderful world of historical research. Your support and friendship through these years have made me realize just how critical all of you have been in shaping my interests and moulding my desires in life. I have learnt a lot which would definitely hold me in good stead all my life. -

Singapore | October 17-19, 2019

BIOPHILIC CITIES SUMMIT Singapore | October 17-19, 2019 Page 3 | Agenda Page 5 | Site Visits Page 7 | Speakers Meet the hosts Biophilic Cities partners with cities, scholars and advocates from across the globe to build an understanding of the importance of daily contact with nature as an element of a meaningful urban life, as well as the ethical responsibility that cities have to conserve global nature as shared habitat for non- human life and people. Dr. Tim Beatley is the Founder and Executive Director of Biophilic Cities and the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. His work focuses on the creative strategies by which cities and towns can bring nature into the daily lives of thier residents, while at the same time fundamentally reduce their ecological footprints and becoming more livable and equitable places. Among the more than variety of books on these subjects, Tim is the author of Biophilic Cities and the Handbook of Bophilic City Planning & Design. The National Parks Board (NParks) of Singapore is committed to enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems of Singapore’s biophilic City in a Garden. NParks is the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife and animal health, welfare and management. The board also actively engages the community to enhance the quality of Singapore’s living environment. Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), NParks, where she leads a team of 30 officers who are responsible for a diverse range of expertise relevant to biodiversity conservation. -

Hillside Address City Living One of the Best Locations for a Residence Is by a Hill

Hillside Address City Living One of the best locations for a residence is by a hill. Here, you can admire the entire landscape which reveals itself in full glory and splendour. Living by the hill – a privilege reserved for the discerning few, is now home. Artist’s Impression • Low density development with large land size. • Smart home system includes mobile access smart home hub, smart aircon control, smart gateway with • Well connected via major arterial roads and camera, WIFI doorbell with camera and voice control expressways such as West Coast Highway and system and Yale digital lockset. Ayer Rajah Expressway. Pasir Panjang • International schools in the vicinity are United World College (Dover), Nexus International School, Tanglin Trust School and The Japanese School (Primary). • Pasir Panjang MRT station and Food Centre are within walking distance. • Established schools nearby include Anglo-Chinese School (Independent), Fairfield Methodist School and Nan Hua Primary School. • With the current URA guideline of 100sqm ruling in • Branded appliances & fittings from Gaggenau, the Pasir Panjang area, there will be a shortage of Bosch, Grohe and Electrolux. smaller units in the future. The master plan for future success 1 St James Power Station to be 2 Housing complexes among the greenery and A NUS and NUH water sports and leisure options. Island Southern Gateway of Asia served only by autonomous electric vehicles. B Science Park 3 Waterfront area with mixed use developments and C Mapletree Business City new tourist attractions, serves as extension of the Imagine a prime waterfront site, three times the size of Marina Bay. That is the central business district with a high-tech hub for untold potential of Singapore’s Master Plan for the Greater Southern Waterfront. -

Best Hidden Gems in Singapore"

"Best Hidden Gems in Singapore" Created by: Cityseeker 17 Locations Bookmarked Singapore Philatelic Museum "Interesting Exhibits" Ever wondered how that stamp in the corner of your envelope was made? Well, that is precisely what you will learn at South-east Asia's first philatelic museum. Opened in 1995, this museum holds an extensive collection of local and international stamps dating back to the 19th century. Anything related to stamps can be found here like first day by Tanya Procyshyn covers, artwork, printing proofs, progressive sheets, even a number of private collections. Equipped with interactive exhibits, audio-visual facilities, a resource center and games, visitors are likely to come away with a new-found interest in stamp collecting. +65 6337 3888 www.spm.org.sg/ [email protected] 23-B Coleman Street, g Singapore Acid Bar "A Secluded Music Cove" Acid Bar occupies a small section of bar Peranakan Place, however do not be deceived by the modest size of this place. The bar is an intimate escape from the hustle of the city life. Illuminated in warm lights and neatly furnished with quaint seating spaces, Acid Bar is the place to enjoy refined drinks while soaking in acoustic tunes. A venue for memorable by Public Domain performances by local artists and bands, Acid Bar is a true hidden gem of the city that is high on nightlife vigor. +65 6738 8828 peranakanplace.com/outle [email protected] 180 Orchard Road, t/acidbar/ m Peranakan Place, Singapore Keepers "Singapore's Shopping Hub" Keepers is a shopping hub, located on Orchard Road. -

Stay Fit & Feel Good Memorable Events at The

INTEGRATED DINING DESTINATION SINGAPORE ISLAND MAP STAY FIT & FEEL GOOD Food warms the soul and we promise that it is always a lavish gastronomic experience Relax after a day of conference meeting or sightseeing. Stay in shape at our 24-hour gymnasium, at the Grand Copthorne Waterfront Hotel. have a leisurely swim in the pool, challenge your travel buddies to a game of tennis or soothe your muscles in the outdoor jacuzzi. MALAYSIA SEMBAWANG SHIPYARD NORTHERN NS11 Pulau MALAYSIA SEMBAWANG SEMBAWANG Seletar WOODLANDS WOODLANDS SUNGEI BULOH WETLAND CHECKPOINT TRAIN CHECKPOINT RESERVE NS10 ADMIRALTY NS8 NS9 MARSILING WOODLANDS YISHUN SINGAPORE NS13 TURF CLUB WOODLANDS YISHUN Pulau SARIMBUN SELETAR RESERVOIR EXPRESSWAY Punggol KRANJI NS7 Barat KRANJI Pulau BUKIT TIMAH JALAN Punggol NS14 KHATIB KAYU Timor KRANJI Pulau Pulau LIM CHU KANG RESERVOIR SELETAR PUNGGOL Serangoon Tekong KRANJI SINGAPORE RESERVOIR PUNGGOL (Coney Island) WAR ZOO AIRPORT Pulau Ubin MEMORIAL NEE LOWER SELETAR NE17 SOON RESERVOIR PUNGGOL Punggol EXPRESSWAY UPPER NIGHT TAMPINES EXPRESSWAY (TPE) LRT (PG) NS5 SAFARI SELETAR YEW TEE RESERVOIR MEMORABLE EVENTS AT THE WATERFRONT (SLE) SERANGOON NE16 RESERVOIR Bukit Panjang SENGKANG RIVER Sengkang LRT (BP) SAFARI With 33 versatile meeting rooms covering an impressive 850 square metres, SENGKANG LRT (SK) CAFHI JETTY NS4 CHOA CHU YIO CHU CHOA CHU KANG KANG CHANGI the Waterfront Conference Centre truly offers an unparalleled choice of meeting KANG NE15 PASIR NS15 BUANGKOK VILLAGE EASTERN DT1 BUKIT YIO CHU KANG TAMPINES EXPRESSWAY (TPE) BUKIT PANJANG (BKE) RIS Boasting a multi-sensory dining experience, interactive Grissini is a contemporary Italian grill restaurant spaces with natural daylight within one of the best designed conference venues PANJANG HOUGANG (KPE) EW1 CHANGI PASIR RIS VILLAGE buffet restaurant, Food Capital showcases the best specialising in premium meats and seafood prepared in DT2 LOWER NS16 NE14 in the region. -

7Th Singapore Raptor Watch Report

7th Singapore Raptor Watch Report 7th Singapore Raptor Watch Report Autumn 2014 Migration - 9 Nov 2014 by TAN Gim Cheong Oriental Honey Buzzards at Telok Blangah Hill Park, 9 Nov 14, by Alan OwYong. The 7th Singapore raptor watch was held on Sunday, 9 November 2014 and involved 52 participants across eight sites. It was another raptor watch of records! Record number of raptors - 2161 raptors counted (previous high was 1022 in the year 2012). - 1933 migrant raptors counted (previous high was 774 in the year 2012). 1 of 6 7th Singapore Raptor Watch Report This year's raptor watch was marked by a shift in 3 sites. Alan OwYong's team returned to Telok Blangah Hill Park after trying out Marina Barrage for the last few years and they were glad they did so as the raptors arrived in numbers over Telok Blangah. Tan Kok Hui & Danny Lau had to shift from Seletar West to Halus Wetlands due to ongoing construction works at their usual site. Lioe Kim Swee's team had to shift from Chek Jawa to Puaka Hill due to works at their usual site and Puaka Hill delivered! The count on Pulau Ubin was also supplemented by a morning count at Pekan Quarry. Puaka Hill, Pulau Ubin Halus Wetlands Pekan Quarry, Pulau Ubin Japanese Gardens Changi Business Park Kent Ridge Telok Blangah Hill Park Tuas South Figure 1 : 2014 Raptor Watch Sites. (source of basemap – maps.google.com.sg) The day started well with fine, partly cloudy weather and held more or less so throughout the day. -

WARTIME Trails

history ntosa : Se : dit e R C JourneyWARTIME into Singapore’s military historyTRAI at these lS historic sites and trails. Fort Siloso ingapore’s rich military history and significance in World War II really comes alive when you make the effort to see the sights for yourself. There are four major sites for military buffs to visit. If you Sprefer to stay around the city centre, go for the Civic District or Pasir Panjang trails, but if you have time to venture out further, you can pay tribute to the victims of war at Changi and Kranji. The Japanese invasion of February 1942 February 8 February 9 February 10 February 13-14 February 15 Japanese troops land and Kranji Beach Battle for Bukit Battle of Pasir British surrender Singapore M O attack Sarimbun Beach Battle Timah PanjangID Ridge to the JapaneseP D H L R I E O R R R O C O A H A D O D T R E R E O R O T A RC S D CIVIC DISTRICT HAR D R IA O OA R D O X T D L C A E CC1 NE6 NS24 4 I O Singapore’s civic district, which Y V R Civic District R 3 DHOBY GHAUT E I G S E ID was once the site of the former FORT CA R N B NI N CC2 H 5 G T D Y E LI R A A U N BRAS BASAH K O O W British colony’s commercial and N N R H E G H I V C H A A L E L U B O administrative activities in the C A I E B N C RA N S E B 19th and 20th century, is where A R I M SA V E H E L R RO C VA A you’ll find plenty of important L T D L E EY E R R O T CC3 A S EW13 NS25 2 D L ESPLANADE buildings and places of interest. -

Japanese Infantry Weapons

RESTRICTED UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET AND PACIFIC OCEAN AREAS JAPANESE INFANTRY WEAPONS CINCPAC • CINCPOA BULLETIN NO. 55-45 15 MARCH 1945 JAPANESE INFANTRY WEAPONS RESTRICTED CINCPAC-CINCPOA BULLETIN 55-49 15 MARCH 1945 FOREWORD Included in this pamphlet, which super sedes CINCPAC-CINCPOA BULLETIN 167-44, are all Japanese weapons reported and encountered,used in infantry regiments or equivalent units. Additional information dealing with heavier weapons, including artillery, anti aircraft and coast defense equipment, has been covered in another publication. Information has been compiled from various sources and includes only pertinent data. Detailed information on specific weapons will be furnished on request. Corrections and add itions will be made from time to time, and recipients are invited to forward additional data to the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Areas. Illustrated methods of neutralizing Japanese weapons most frequently encountered by Allied forces also are contained in this pamphlet. Additional copies are available on request. JAPANESE INFANTRY WEAPONS RESTRICTED CINCPAC-CINCPOA BULLETIN SS-4S IS MARCH 1945 TABLE OF CONTENTS Standard Hand Grenades 1 Other Hand Grenades 4 Rifle Grenades and Grenade Launchers 7 Anti-Tank Vines ' 9 Pistols 12 6.5 MM Rifles 14 7.7 MM Rifles 16 Submachine Guns IS 6.5 MM Light Machine Gun Model 11 (1922) 19 6.5 MM Light Machine Gun Model 96 (1936) 21 7.7 MM Light Machine Gun Model 99 (1939) 23 7.7 MM Tank Machine Gun Model 97 (1937) 25 7.92 MM Light Machine Gun. Bren Type 27 6.5 -

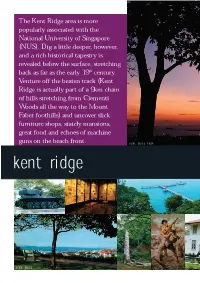

Kent Ridge Area Is More Popularly Associated with the National University of Singapore (NUS)

The Kent Ridge area is more popularly associated with the National University of Singapore (NUS). Dig a little deeper, however, and a rich historical tapestry is revealed below the surface, stretching back as far as the early 19 th century. Venture off the beaten track (Kent Ridge is actually part of a 9km chain of hills stretching from Clementi Woods all the way to the Mount Faber foothills) and uncover slick furniture shops, stately mansions, great food and echoes of machine guns on the beach front. KENT RIDGE PARK kent ridge KENT RIDGE west 2 3 Your first stop should be Kent Further south are the psychedelic Ridge Park (enter from South statues of Haw Par Villa (Pasir Buona Vista Road). Climb or jog Panjang Road). And moving to the top of the bluff for a eastwards is the superb museum, panoramic sweep of the ships Reflections at Bukit Chandu parked in the harbour far below. (31K Pepys Road), a two-storey The area is a regular haunt for bungalow that commemorates, fitness freaks out for their daily via stunning holographic and jog from the adjoining university. interactive shows, the Battle of If you have time, join the Bukit Chandu that was bravely fascinating eco-tours conducted led by a Malay regiment. by the Raffles Museum of Another popular destination in Biodiversity and Research the area is Labrador Park (enter REFLECTIONS AT BUKIT CHANDU (Block S6, Level 3, NUS). from Alexandra Road). Dating back to the 19 th century, the park was the site of a battlement guarding the island against invasion from the sea.