Atmospheric Heating and Global Winds and Local Winds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Concepts in Oceanography

Chapter 1 XA0101461 BASIC CONCEPTS IN OCEANOGRAPHY L.F. SMALL College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, United States of America Abstract Basic concepts in oceanography include major wind patterns that drive ocean currents, and the effects that the earth's rotation, positions of land masses, and temperature and salinity have on oceanic circulation and hence global distribution of radioactivity. Special attention is given to coastal and near-coastal processes such as upwelling, tidal effects, and small-scale processes, as radionuclide distributions are currently most associated with coastal regions. 1.1. INTRODUCTION Introductory information on ocean currents, on ocean and coastal processes, and on major systems that drive the ocean currents are important to an understanding of the temporal and spatial distributions of radionuclides in the world ocean. 1.2. GLOBAL PROCESSES 1.2.1 Global Wind Patterns and Ocean Currents The wind systems that drive aerosols and atmospheric radioactivity around the globe eventually deposit a lot of those materials in the oceans or in rivers. The winds also are largely responsible for driving the surface circulation of the world ocean, and thus help redistribute materials over the ocean's surface. The major wind systems are the Trade Winds in equatorial latitudes, and the Westerly Wind Systems that drive circulation in the north and south temperate and sub-polar regions (Fig. 1). It is no surprise that major circulations of surface currents have basically the same patterns as the winds that drive them (Fig. 2). Note that the Trade Wind System drives an Equatorial Current-Countercurrent system, for example. -

Rain Shadows

WEB TUTORIAL 24.2 Rain Shadows Text Sections Section 24.4 Earth's Physical Environment, p. 428 Introduction Atmospheric circulation patterns strongly influence the Earth's climate. Although there are distinct global patterns, local variations can be explained by factors such as the presence of absence of mountain ranges. In this tutorial we will examine the effects on climate of a mountain range like the Andes of South America. Learning Objectives • Understand the effects that topography can have on climate. • Know what a rain shadow is. Narration Rain Shadows Why might the communities at a certain latitude in South America differ from those at a similar latitude in Africa? For example, how does the distribution of deserts on the western side of South America differ from the distribution seen in Africa? What might account for this difference? Unlike the deserts of Africa, the Atacama Desert in Chile is a result of topography. The Andes mountain chain extends the length of South America and has a pro- nounced influence on climate, disrupting the tidy latitudinal patterns that we see in Africa. Let's look at the effects on climate of a mountain range like the Andes. The prevailing winds—which, in the Andes, come from the southeast—reach the foot of the mountains carrying warm, moist air. As the air mass moves up the wind- ward side of the range, it expands because of the reduced pressure of the column of air above it. The rising air mass cools and can no longer hold as much water vapor. The water vapor condenses into clouds and results in precipitation in the form of rain and snow, which fall on the windward slope. -

Hurricane Paths: Comparing Places with Different Prevailing Winds

Name ___________________________ Hurricane Paths: Comparing Places with Different Prevailing Winds To understand where hurricanes usually start and what direction they usually move, it helps to have a clear mental image of the pattern of prevailing winds in the world. One way to get this image is to make a careful comparison of wind observations in several places. The diagrams on the right are examples of a special kind of graph called a wind rose. The number in the center indicates the percentage of time the air is calm (no wind). Each of the eight lines radiating away from the center shows the percentage of time the wind blows FROM that direction. Repeat: The lines point to the direction the wind is blowing FROM. Please answer the following questions. 1) According to the map above, Boston has calm air about 12% of the time; the percentage of time San Juan, Puerto Rico, has calm air is _____ . 2) In San Juan, the wind blows the largest percentage of time from the northeast; in Boston, the wind blows from the _________ more often than from any other direction. 3) Use the wind rose graphs on pages 2 and 3. To get an idea about the net zonal flow of air in each location, add up the total percentage of time the wind blows from the southwest, west, and northwest, and subtract the total percentage from the southeast, east, and northeast total percentage. The result is the net westerly component - it is a positive number if the flow is mainly westerly (from the west), and a negative number if the flow is easterly (from the east). -

Prevailing Wind Park Energy Facility Draft Environmental Assessment

Prevailing Wind Park Energy Facility Draft Environmental Assessment DOE/EA-2061 January 2019 Prevailing Wind Park Energy Facility Draft Environmental Assessment Bon Homme, Charles Mix, Hutchinson, and Yankton Counties, South Dakota U.S. Department of Energy Western Area Power Administration DOE/EA-2061 January 2019 Prevailing Wind Park Draft EA Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 WAPA’s Purpose and Need ................................................................................. 1-3 1.2 Prevailing Wind Park’s Goals and Objectives ..................................................... 1-3 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED ACTION AND NO ACTION ALTERNATIVES ............................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Proposed Action ................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1.1 Prevailing Wind Park Project ................................................................ 2-1 2.1.2 Project Life Cycle ................................................................................. 2-5 2.2 No Action Alternative .......................................................................................... 2-5 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................ 3-1 3.1 Land Cover and Land Use .................................................................................. -

FINAL REPORT Wind Assessment For: BANKSTOWN

FINAL REPORT Wind Assessment for: BANKSTOWN COMPASS CENTRE 83-99 North Terrace & 62 The Mall, Bankstown Sydney, NSW 2200, Australia Prepared for: Fioson Pty Ltd L34, 225 George St Sydney NSW 2000 CPP Project: 8759 October 2016 Prepared by: Thomas Evans, Engineer Graeme Wood, Ph.D., Director CPP Project 8759 Executive Summary This report provides an opinion based qualitative assessment of the impact of the proposed Bankstown Compass Centre development on the local pedestrian-level wind environment. This assessment is based on knowledge of the local Bankstown wind climate and previous wind- tunnel test on similar buildings in the Bankstown area. The proposed development is taller than surrounding buildings. Wind speeds are expected to be higher around the outer corners of the development, though the podium roof will prevent significant wind effects occurring at street level. The environmental wind conditions at ground level around the proposed development are expected to be suitable for pedestrian standing from a comfort perspective and pass the distress criterion. Within the development, wind conditions are expected to be suitable for pedestrian standing or walking activities and pass the distress criterion under Lawson. For such a large development with several similar sized towers designed in such a complex manner, it would be recommended to quantify the wind conditions and confirm the qualitative findings using wind-tunnel testing. ii CPP Project 8759 DOCUMENT VERIFICATION Prepared Checked Approved Date Revision by by by 04/02/16 Final Report KF GSW GSW 10/02/16 Revision 1 KF GSW GSW 04/10/16 Amended design drawings TE GSW GSW 05/10/16 Amended Figure TE GSW GSW TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... -

T5.1 the Dynamics of Nova Scotia's Climate

PAGE .............................................................. 94 ▼ T5.1 THE DYNAMICS OF NOVA SCOTIA’S CLIMATE The main features of Nova Scotia’s climate are am- MAJOR AIR MASSES ple and reliable precipitation, a fairly wide but not extreme temperature range, a late and short sum- Satellite photography, computer modelling, a greater mer, skies that are often cloudy or overcast, frequent knowledge of the structure of weather systems and a coastal fog and marked changeability of weather better understanding of the physical processes that from day to day. These features can be related to four control our weather have all led to a much-reduced basic factors: use of air-mass concepts. Air-mass theory is still 1. the prevailing westerly winds used descriptively, however, and is very useful to 2. the interactions between the three main air introduce people to the disciplines of meteorology masses which converge on the east coast and climatology. 3. Nova Scotia’s position astride the routes of the Much of the variability of the weather is caused by major eastward-moving storms the shifting positions of the three main air masses T5.1 4. the modifying influence of the sea that dominate the eastern seaboard. Continental The Dynamics of arctic air from the northwest is very dry and cold in Nova Scotia’s WIND SYSTEMS winter. Maritime polar air, moving in from the north Climate or northeast, has been somewhat warmed by its The basic eastward movement of the wind systems passage over the ocean and is cool and moist. Mari- (known as the westerlies) over North America is a time tropical air from the south or southwest is warm result of the general circulation of warm air from the and moist. -

Global Wind Patterns

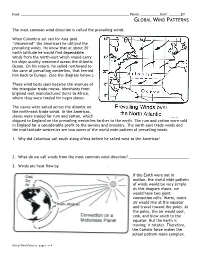

NAME: _______________________________________________________________ PERIOD: ___________ DATE: _______EN GLOBAL WIND PATTERNS The most common wind direction is called the prevailing winds. When Columbus set sail for Asia (and “discovered” the Americas) he utilized the prevailing winds. He knew that at about 20° north latitude he would find dependable winds from the north-east which would carry his ships quickly westward across the Atlantic Ocean. On his return, he sailed northward to the zone of prevailing westerlies, that ferried him back to Europe. (See the diagram below.) These wind belts soon became the avenues of the triangular trade routes. Merchants from England sent manufactured items to Africa, where they were traded for negro slaves. The slaves were sailed across the Atlantic on the north-east trade winds. In the Americas, the slaves were traded for rum and cotton, which were shipped to England on the prevailing westerlies farther to the north. The rum and cotton were sold in England for a considerable profit to the owners and investors. The north-east trade winds and the mid-latitude westerlies are two zones of the world wide pattern of prevailing winds. 1. Why did Columbus sail south along Africa before he sailed west to the Americas? 2. What do we call winds from the most common wind direction? 3. Winds are heat flow by . If the Earth were not in motion, the world wide pattern of winds would be very simple. As this diagram shows, we would have two giant convection cells. Warm, moist air would rise at the equator and travel toward the poles. -

Global Climate Zones Id: an Idealized Simple View

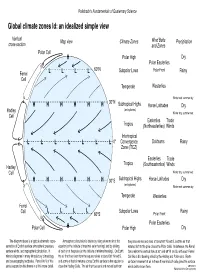

Railsback's Fundamentals of Quaternary Science Global climate zones Id: an idealized simple view Vertical Map view Climate Zones Wind Belts Precipitation cross-section and Zones Polar Cell H Polar High Dry Polar Easterlies 60°N Subpolar Lows Polar Front Rainy Ferrel L L L L Cell Temperate Westerlies Winter wet; summer dry 30°N H H H H H H Subtropical Highs Horse Latitudes Dry (anticyclones) Hadley Winter dry; summer wet Cell Easterlies Trade Tropics (Northeasterlies) Winds Intertropical L L L L L L L 0° Convergence Doldrums Rainy Zone (ITCZ) Easterlies Trade Tropics (Southeasterlies) Winds Hadley Cell Winter dry; summer wet H H H H H H 30°S Subtropical Highs Horse Latitudes Dry (anticyclones) Winter wet; summer dry Temperate Westerlies Ferrel Cell L L L L Subpolar Lows Rainy 60°S Polar Front Polar Easterlies Polar Cell H Polar High Dry The diagram above is a typical schematic repre- Atmospheric circulation is driven by rising of warm air at the the poles warms and rises at about 60° N and S, and the air that sentation of Earth's surface atmospheric pressure, equator (at the latitude of maximal solar heating) and by sinking returns aloft to the pole closes the Polar Cells. In between, the Ferrel surface winds, and tropospheric circulation. It of cold air at the poles (at the latitude of minimal heating). On Earth, Cells mirror the vertical flow at 30° and 60° N and S, with each Ferrell mimics diagrams in many introductory climatology the air that has risen from the equator sinks at about 30° N and S, Cell like a ball bearing rolled by the Hadley and Polar cells. -

Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (Pp

Chapter 7 - Title Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (pp. 165-195) Contents • scales of motion and turbulence • local winds • the General Circulation of the atmosphere • ocean currents Wind Examples Fig. 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion. Microscale → mesoscale → synoptic scale. Scales of Motion • Microscale – e.g. chimney – Short lived ‘eddies’, chaotic motion – Timescale: minutes • Mesoscale – e.g. local winds, thunderstorms – Timescale mins/hr/days • Synoptic scale – e.g. weather maps – Timescale: days to weeks • Planetary scale – Entire earth Scales of Motion Table 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion Turbulence • Eddies : internal friction generated as laminar (smooth, steady) flow becomes irregular and turbulent • Most weather disturbances involve turbulence • 3 kinds: – Mechanical turbulence – you, buildings, etc. – Thermal turbulence – due to warm air rising and cold air sinking caused by surface heating – Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) - due to wind shear, i.e. change in wind speed and/or direction Mechanical Turbulence • Mechanical turbulence – due to flow over or around objects (mountains, buildings, etc.) Mechanical Turbulence: Wave Clouds • Flow over a mountain, generating: – Wave clouds – Rotors, bad for planes and gliders! Fig. 7.2: Mechanical turbulence - Air flowing past a mountain range creates eddies hazardous to flying. Thermal Turbulence • Thermal turbulence - essentially rising thermals of air generated by surface heating • Thermal turbulence is maximum during max surface heating - mid afternoon Questions 1. A pilot enters the weather service office and wants to know what time of the day she can expect to encounter the least turbulent winds at 760 m above central Kansas. If you were the weather forecaster, what would you tell her? 2. -

Chapter 6 Climate

Chapter 6 Climate Climate . Canada's climate is not as cold all year around as some may believe. In winter, temperatures fall below freezing point throughout most of Canada. But the south- western coast has a relatively mild climate. Along the Arctic Circle, mean temperatures are below freezing for seven months a year. Climate . During the summer months the southern provinces often experience high levels of humidity and temperatures that can surpass 30 degrees Celsius regularly. Western and south-eastern Canada experience high rainfall, but the Prairies are dry with 250 mm to 500 mm of rain every year. Weather/Climate . Weather – Is the result of the day-to-day conditions of the atmosphere. Climate – A long term pattern of weather – Climate Is The Weather + Weather + More Weather . Climate is what you expect, weather is what you get! Weather . Types of things given in a weather forecast: – Temperature Precipitation – Humidity Wind speed/direction – Cloud cover Air pressure Climate . Factors that affect climate (J.BLOWER); – Jet Stream (air masses) – Bodies of water – Latitude – Ocean Currents – Winds – Elevation – Relief . Note: Different parts of Canada have different climates. Factors that affect Climate A. Jet Stream (Air Masses) Air Masses -- is a large body of air that has similar temperature and moisture properties throughout. For example: Winds blowing from a cold region will bring cold temperature conditions to an area over which they pass Factors that affect Climate . B. Bodies of water – Water warms up more slowly than land and cools off more slowly – As a result of this, land near bodies of water are affected by the weather over these bodies of water. -

FOSS Weather and Water Course Vocabulary/Glossary Terms Second Edition © 2014 Investigations Guide Vocabulary Investigation 1

FOSS Weather and Water Course Vocabulary/Glossary Terms Second Edition © 2014 Investigations Guide Vocabulary Investigation 1: What Is Weather? Investigation 4: Convection air pressure convection climate convection cell forecast energy transfer humidity fluid meteorologist model meteorology precipitation Investigation 5: Heat Transfer prediction absorb severe weather climatologist temperature climatology weather differential heating wind evidence heat Investigation 2: Where’s the Air? latitude air radiant energy atmosphere radiation compress ray exosphere solar angle expand wave mass matter Investigation 6: Air Flow mesosphere air mass particle conduction permanent gas Coriolis effect pressure jet stream state land breeze stratosphere prevailing winds thermosphere sea breeze troposphere variable gas Investigation 7: Water in the Air weight condensation condensation nucleus Investigation 3: Air Pressure and Wind dew point atmospheric pressure evaporation bar precipitation barometer saturated density transpiration equilibrium isobar Investigation 8: Meteorology kinetic energy cold front millibar (mb) radiosonde warm front FOSS Weather and Water, Second Edition: Course Vocabulary/Glossary Terms 1 of 4 Investigation 9: The Water Planet El Niño groundwater gyre ocean current salinity water cycle Investigation 10: Climate over Time carbon dioxide carbon sequestration climate change emission global warming greenhouse effect greenhouse gas ice core infrared paleoclimatology pollutant FOSS Weather and Water, Second Edition: Course Vocabulary/Glossary -

Climatology of Tropical Cyclones in New England and Their Impact at the Blue Hill Observatory, 1851-2012

Climatology of Tropical Cyclones in New England and Their Impact at the Blue Hill Observatory, 1851-2012 Michael J. Iacono Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory Updated September 2013 Introduction Over the past four centuries, extreme hurricanes have occurred in New England at intervals of roughly 150 years, as evidenced by the three powerful storms of 1635, 1815, and 1938. Histories and personal accounts of these infamous hurricanes make for fascinating reading (Ludlum, 1963; Minsinger, 1988), and they serve as an important reminder of the devastating impact that tropical cyclones can have in the Northeast. Most tropical systems in New England are less damaging, but they can still disrupt our daily lives with strong winds, heavy rain, and flooding. This article, which updates an earlier report in the Blue Hill Observatory Bulletin (Iacono, 2001), will describe the climatology of all 250 tropical cyclones that have affected New England since the mid-19th century and will summarize their intensity, frequency, and specific meteorological impact at the Blue Hill Observatory. A hurricane is a self-sustaining atmospheric process in which sunlight, water, and wind combine to transfer energy from the tropics to higher latitudes. The uneven distribution of solar heating at the Earth’s surface ultimately drives much of our weather as the atmosphere continually circulates to equalize the tropical warmth and the polar cold. In the tropics, this process is normally tranquil and slow, brought about through the life cycles of individual thunderstorms, the prevailing winds, and ocean currents. However, under the right conditions very warm air and water in the tropics trigger the formation of the most efficient heat transfer mechanism available to the atmosphere: a hurricane.