Education and Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2019

JANUARY 2019 Monday-Friday Daytime Schedule 1 TUESDAY 7:30 Colorado Experience "The Redstone Castle" Built by the “Fuel King of the West,” All programming subject to change 7:00 We'll Meet Again "Escape from Cuba" Join John C. Osgood, this “Ruby of the Rockies” a. m. morning p. m. afternoon/evening Ann Curry as two men search for the people represents the exquisite styles and social who helped them come to the U.S. when a culture of 20th century American elite. This = Rocky Mountain PBS original program they fled Castro's Cuba. (Date) = shown on this date only castle stands as a monument to the empire 8:00 Great Performances "From Vienna: The New built by one of Colorado’s most successful 4:30 Painting and Travel with Roger & Year's Celebration 2019" Ring in the New entrepreneurs and represents a change in Sarah Bansemer Year with the Vienna Philharmonic under the social policy concerning labor management 5:00 Priscilla's Yoga Stretches baton of conductor Christian Thielemann at relations. Explore the extravagant halls of 5:30 Classical Stretch: By Essentrics the Musikverein. Hosted by Hugh Bonneville the Redstone Castle and learn of its struggle and featuring favorite Strauss Family waltzes 6:00 Peg + Cat for survival through multiple owners and accompanied by the dancing of the Vienna flirtation with destruction. a 6:30 Arthur City Ballet. 7:00 Ready Jet Go! 8:00 Pioneers of Television "Primetime Soaps" 9:30 Memory Rescue with Daniel Amen, MD "Dallas" and "Dynasty" kicked off the 7:30 Wild Kratts Dr. -

SPRING 2006 3 in the L NEWS

PITZER COLLEGE SPRIN G 2 0 0 6 • MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS pART I c I pANT VOLUME 4 FOR THE FOURTH CONSECUTIVE YEAR AMONG COLLEGES OUR SIZE PITZER COLLEGE FIRST TH INGS MAGA7.1Nl l <>• •'""'" "" rRILNI)\ PA R.T I C I PANT FIRST President Lauro Skondero Trombley Jenniphr Goodman '84 Wins Editor Susan Andrews Managing Editor Third Annual Alumni Award Joy Collier Designer Emily Covolconti he Third Annual Distinguished Alumni Sports Editor Award was presented Catherine Okereke '00 T during Alumni Weekend on Contributing Writers April29 at the All Class Susan Andrews Reunion Dinner. The award, Carol Brandt the highest honor bestowed Richard Chute '84 upon a graduate of Pitzer Joy Collier College, recognizes an alum Pamela David '74 na/us who has brought Tonyo Eveleth honor and distinction to the Alice Jung '0 1 College through her or his Peter Nardi outstanding achievements. Catherine Okereke '00 This year, the College hon Norma Rodriguez ored the creative energy of Shell (Zoe) Someth '83 an alumna and her many Sherri Stiles '87 achievements in film produc linus Yamane tion. Jenniphr Goodman, a 1984 graduate of Pitzer, Contributing Photographers embodies the College's com Emily Covolconti mitment to producing Phil Channing engaged, socially responsi Joy Collier ble, citizens of the world. Robert Hernandez '06 After four amazing years Alice Maple '09 at Pitzer, Jenniphr received Donald A. McFarlane her B.A. in creative writing Catherine Okereke '00 and film making in 1984. She Distinguished Alumni Award recipient Jenniphr Goodman '84 wilh Kirk Reynolds returned to her hometown in Professor of English and the History of Ideas Barry Sanders Cover Des ign Cleveland, Ohio, to teach art Emily Covolconti to preschool children after Award in 1993 at Pitzer College, to graduating. -

Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA 661 Millwood Avenue, Ste 206 Winchester, Virginia USA 22601

LORNE BAIR RARE BOOKS CATALOG 26 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA 661 Millwood Avenue, Ste 206 Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with or- der and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ strict standards of professionalism and ethics. CONTENTS OF THIS CATALOG _________________ AFRICAN AMERICANA Items 1-35 RADICAL & PROLETARIAN LITERATURE Items 36-97 SOCIAL & PROLETARIAN LITERATURE Items 98-156 ART & PHOTOGRAPHY Items 157-201 INDEX & REFERENCES PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. ANDREWS, Matthew Page Heyward Shepherd, Victim of Violence. [Harper’s Ferry?]: Heyward Shepherd Memorial Association, [1931]. First Edition. Slim 12mo (18.5cm.); original green printed card wrappers, yapp edges; 32pp.; photograph. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Programs & Exhibitions

PROGRAMS & EXHIBITIONS Winter/Spring 2020 To purchase tickets by phone call (212) 485-9268 letter | exhibitions | calendar | programs | family | membership | general information Dear Friends, Until recently, American democracy wasn’t up for debate—it was simply fundamental to our way of life. But things have changed, don’t you agree? According to a recent survey, less than a third of Americans born after 1980 consider it essential to live in a democracy. Here at New-York Historical, our outlook is nonpartisan Buck Ennis, Crain’s New York Business and our audiences represent the entire political spectrum. But there is one thing we all agree on: living in a democracy is essential indeed. The exhibitions and public programs you find in the following pages bear witness to this view, speaking to the importance of our democratic principles and the American institutions that carry them out. A spectacular new exhibition on the history of women’s suffrage in our Joyce B. Cowin Women’s History Gallery this spring sheds new light on the movements that led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution 100 years ago; a major exhibition on Bill Graham, a refugee from Nazi Germany who brought us the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, and many other staples of rock & roll, stresses our proud democratic tradition of welcoming immigrants and refugees; and, as part of a unique New-York Historical–Asia Society collaboration during Asia Society’s inaugural Triennial, an exhibition of extraordinary works from both institutions will be accompanied by a new site-specific performance by drummer/composer Susie Ibarra in our Patricia D. -

Program Guide

JANUARY 2019 VOL. 49 NO. 1 PROGRAM GUIDE New Season 8 premiering Saturday, January 5, at 9:00 p.m. NEW YEAR'S NEW SERIES "VICTORIA" RETURNS SPECIALS "SHAKESPEARE & HATHAWAY" FOR SEASON 3 Page 2 Page 7 Page 7 MONDAY – FRIDAY 6:00 Peg + Cat 6:30 Arthur 7:00 Ready Jet Go! 7:30 Wild Kratts 8:00 Nature Cat 8:30 Curious George 9:00 Let's Go Luna! NEW YEAR’S EVE 9:30 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood 9:00 p.m. 10:00 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood 10:30 Pinkalicious & Peterrific LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER 11:00 Sesame Street New York Philharmonic New Year’s Eve 11:30 Splash and Bubbles with Renee Fleming Ring in the New Year with the New York Philharmonic and opera 12:00 Dinosaur Train great Renee Fleming. 12:30 The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That! 10:30 p.m. 1:00 Sesame Street 1:30 Super WHY! Austin City Limits Hall of Fame Celebrate the induction of new Austin City Limits Hall of Famers 2:00 Pinkalicious & Peterrific Ray Charles, Los Lobos and Marcia Ball, with performances by 2:30 Let's Go Luna! Boz Scaggs, Gary Clark Jr., Norah Jones and more. 3:00 Nature Cat 3:30 Wild Kratts 4:00 Wild Kratts NEW YEAR’S DAY 4:30 Odd Squad Noon–5:30 p.m. 5:00 Odd Squad Get help starting your New Year’s resolution with an afternoon of 5:30 Weather World self-help programming. (Re-airs at 5:45 p.m.) 6:00 BBC World News America 9:00 p.m. -

WSKG-HDTV Dec 2018

1 next for the #MeToo movement. of Representatives, discusses the 5 Wednesday American conservative movement. 8pm Reindeer Family & Me 8 Saturday 9pm Martin Clunes: Islands of 8pm Midsomer Murders Australia Midsomer Life, Part 1 10pm Martin Clunes: Islands of The detectives investigate when WSKG-HDTV Australia the ex-wife's lover of the owner of 11pm Martin Clunes: Islands of Midsomer Life magazine dies. Dec 2018 Australia 9pm Father Brown expanded listings 12am Amanpour and Company The Crackpot of the Empire 10pm Are You Being Served? 6 Thursday The Club 1 Saturday 8pm Expressions (WSKG) Songs of the Season 10:30pm Are You Being Served? 8pm Members' Choice 9pm 800 Words Do You Take This Man? 12am Members' Choice The first anniversary of his wife's 11pm Still Open All Hours 2 Sunday death looms large for George as Christmas 2016 8pm Members' Choice war breaks out with the in-laws. As Christmas approaches, grocer 12am Members' Choice 10pm Doc Martin Granville's cost-saving measures at 3 Monday Rescue Me his shop are as cunning as ever. Life in Portwenn transpires to get in 11:30pm Austin City Limits 8pm Antiques Roadshow Band of Horses/Parker Millsap Albuquerque, Hour Two Martin's way as he questions if Louisa will come back to him. Enjoy modern roots rock with Band Great finds include a 1969 Jasper of Horses. Parker Millsap supports Johns flag print and a 1939 11pm Doc Martin The Shock of the New The Very Last Day. inscribed "Pinocchio" book. 12:30am Front and Center 9pm Expressions (WSKG) Martin may have me this match after Martin's first session with Dr. -

Defy Bus Racial Segregation in Montgomery

1956 — A Year of RevolutionaryStruggle t h e (See Page 3) I MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Vol. XX - No. 53 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, DECEMBER 31, 1956 Price 10 Cents Fryer’s Book Nails Stalinists Defy Bus Racial Segregation On Hungary By John White MANCHESTER, ENGLAND, Dec. 21 — Peter Fryer, In Montgomery, Tallahassee former London Daily Worker correspondent in Hungary, has now published a book, Hungarian Tragedy. It is based ■on what he saw in the 14 mo »-■ ------------------------------------------------- mentous days of his last visit ed to the London Daily Worker So. Africans Negroes Take Any Seats to Hungary. and the Stalinists who con When Fryer went there on trol it taught him another lesson Oct. 27, the Hungarian revolu when they suppressed his dis Fight Racial tion was less than four days old. patches. He le ft H u n g a ry on Nov. 10. First Time in History; He was there while the masses were flushed with victory after Those 14 days decisively turned Oppression their first uprising. He saw the Fryer from a Stalinist journalist development of dual power, with into a bitter and caustic oppo By Fred Halstead the armed working class and stu nent of the leadership of the Birmingham Opens Fight Last week, South African op British Communist Party. dents, organized in revolution ponents of racial segregation He quotes Pollitt’s advice to By Myra Tanner Weiss ary committees jealous of their displayed great courage and de a Communist Party member virile and surging democracy on termination in their struggle DEC. -

JANUARY 1998 NUMBER 1 President's SFPD #1 in Combined Charities Ay John Ehrlich, Support Services Tor Rate of Any Large Unit

Member of COPS California Organization of !1 Police & Sheriffs 3 All SAN FRANCISCO POLICE OFFICERS' ASSOCIATION To Promote the Ideals, Policies and Accomplishments of the Association and its Members VOLUME 30 SAN FRANCISCO, JANUARY 1998 NUMBER 1 President's SFPD #1 in Combined Charities Ay John Ehrlich, Support Services tor rate of any large unit. This speaks well for our ace detectives who have Message The members of the SFPJ) contrib- not lost touch with the needs in the community. Last year in a different By Chris Cunnie, President uted more money than any other Department in the San Francisco unit Greg Corales had correspond- ingly high totals. swe close the books on 1997, City and County Combined Charity Teresa Valdivia helped include the let me express my extreme Campaign. We raised more than one Airport Bureau in the spirit and they Agratitude to all of you for your third more than the next highest gave over $9,000. They were the num- confidence and support throughout Department. While the final totals ber three unit in dollars donated. another difficult and challenging year are not yet in, over 1,000 people in Judy Hogan at Communications in the live, on-going saga of the San the SFPD gave over $92,000. organized a drive where over 50 of Francisco Police Officers' Associa- We have amazed people in the our dispatchers gave over $4,600. All tion. Charitable Community in that only three watches participated in the I often sit at my desk, telephone two years ago we were raising only a 500% increase in giving from last ringing, calls waiting, members sit- fraction of this amount. -

January 2019 New Season

JANUARY 2019 Program Guide NEW SEASON SUN JAN 13 @ 8PM 316-838-3090 •kpts.org [email protected] • 316-838-3090 Special New Year's Day programs 8AM & 3:30PM to help you begin the year inspired. Memory Rescue with Daniel Amen, M.D. 10AM Aging Backwards 2: Connective Tissue Revealed with Miranda Esmonde-White Noon New Year Healthy Brain - Happy Life with Dr. Suzuki 2PM New Outlook 3 Steps to Incredible Health with Tuesday, January 1 @ 8AM - 5PM Joel Fuhrman, M.D. Tuesday, January 1 @ 8PM Ring in the New Year with the Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of conductor Christian Thielemann at the Musikverein. Hosted by Hugh Bonneville and featuring favorite Strauss Family waltzes accompanied by the dancing of the Vienna City Ballet. Wednesday, January 2 @ 8PM The New Horizons spacecraft attempts to fly by a mysterious object Pluto and Beyond known as Ultima Thule, believed to be a primordial building block of the solar system. Three years after taking the first spectacular photos of Pluto, New Horizons is four billion miles from Earth, trying to achieve the most distant flyby in NASA’s history. If successful, it will shed light on one of the least understood regions of our solar system: the Kuiper Belt. NOVA is embedded with the New Horizons mission team, following the action in real time as they uncover the secrets of what lies beyond Pluto. Saturday, January 5 @ 9PM Season 8 Saturdays @ 8PM Beginning January 5 January 5 Mysterious Ways After successfully rekindling their relationship, Louisa and Martin are living together again, but Louisa finds herself juggling too many responsibilities at once. -

Warrior Bards

WARRIOR BARDS by Kevin McCarthy & Michael E. Tigar A Performance in Six Scenes [Note: This play was originally performed in San Francisco by Kevin McCarthy. It is written for performance by one actor who portrays all five lawyers, using changes of dress, demeanor and style to mark their differences, while preserving the theme that their work is unified. It could be done by a series of actors.] COPYRIGHT (C) 1989 KEVIN MCCARTHY & MICHAEL E. TIGAR ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Warrior Bards, Page 1 [The curtain rises on a stage set with a standup writing desk, a comfortable chair, a lectern, a hall tree, and an easel. On the easel is set a large portrait of Dan O'Connell, in the costume in which we will first see him. The hall tree has hooks to hang coats and hats and a mirror, in order to permit the actor to check his appearance when changing characters. There will also be a low railing to represent a jury rail. Among the props will be a copy of the New York Times for Malone, a copy of a book of judicial decisions, a schoolhouse ruler, and other items.] Scene One [Daniel O'Connell enters, wearing a cloak and shovel hat as depicted in pictures of him. Under the cloak he may have on a barrister's robe, and may then put on a wig. He is large, robust, energetic. He would probably have a habit of running his hands through his hair, which was curled and unruly. He has a gentle, cajoling voice. He may roll his eyes to emphasize a point.] [A lawyer who saw O'Connell (Sheil) describes O'Connell as "five-feet eleven and one- half inches, with a high forehead. -

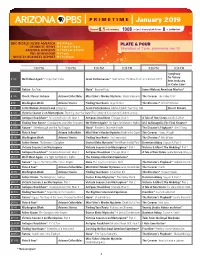

January 2019

January 2019 Channel 8.1 with antenna 1008 on Cox & CenturyLink Prism, 8 on Suddenlink BBC WORLD NEWS AMERICA M-F 4:30 p.m. PLATE & POUR CRONKITE NEWS M-F 5 p.m. & 11 p.m. Thursdays at 7 p.m., premiering Jan. 10 ARIZONA HORIZON M-F 5:30 p.m. & 10 p.m. PBS NEWSHOUR M-F 6 p.m. NIGHTLY BUSINESS REPORT M-F 10:30 p.m. 7:00 P.M. 7:30 P.M. 8:00 P.M. 8:30 P.M. 9:00 P.M. 9:30 P.M. Symphony for Nature: 1 TUE We'll Meet Again* Escape from Cuba Great Performances* From Vienna: The New Year's Celebration 2019 Britt Orchestra at Crater Lake* 2 WED Nature Fox Tales Nova* Beyond Pluto James Watson: American Masters* 3 THU Check, Please! Arizona Arizona Collectibles Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries Death & Hysteria The Coroner The Foxby Affair 4 FRI Washington Week Arizona Stories Finding Your Roots Map of Stars The Directors* Alfred Hitchcock 5 SAT Celtic Woman: Ancient Land (at 6 p.m.) Great Performances Michael Buble: Tour Stop 148 Desert Dreams 6 SUN Victoria Season 2 on Masterpiece The King Over the Water/The Luxury of Conscience/Comfort and Joy 7 MON Antiques Roadshow* Meadow Brook Hall, Hour 1 Antiques Roadshow Chicago, Hour 1 A Tale of Two Sisters Amelia Earhart 8 TUE Finding Your Roots* Grandparents and Other Strangers We'll Meet Again* The Fight for Women's Rights USS Indianapolis: The Final Chapter* 9 WED Nature* Attenborough and the Sea Dragon Nova* Einstein's Quantum Riddle The Dictator's Playbook* Kim Il Sung 10 THU Plate & Pour* Arizona Collectibles Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries Death at the Grand The Coroner Pieces of Eight 11 FRI Washington