Opening the Frontier Closed Area: a Mutual Benefit Zone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Hong-Kong, Kau-Lung and Adjacent Territories Stock#: 64206 Map Maker: Bartholomew Date: 1898 circa Place: Color: Color Condition: VG Size: 15.5 x 11.5 inches Price: SOLD Description: Rare separately published map of Hong Kong, published by John Bartholomew and the Edinburgh Geographical Institute. The map illustrates the boundaries set up by the Territorial Convention of 1860 and the New Convention of 1898. The map was issued shortly after the signing of the New Convention on June 9, 1898. Under the convention the territories north of what is now Boundary Street and south of the Sham Chun River, and the surrounding islands, later known as the "New Territories" were leased to the United Kingdom for 99 years rent-free, expiring on 30 June 1997, and became part of the crown colony of Hong Kong. The Kowloon Walled City was excepted and remained under the control of Qing China. The territories which were leased to the United Kingdom were originally governed by Xin'an County, Guangdong province. Claude MacDonald, the British representative during the convention, picked a 99- year lease because he thought it was "as good as forever". Britain did not think they would ever have to give the territories back. The 99-year lease was a convenient agreement. Rarity We were unable to find an institutional examples of the map. A smaller version of the map appeared the in Europe in China: The History of Hong Kong from the Beginning to the Year 1882, published in 1899. -

San Tin / Lok Ma Chau Development Node Project Profile

Civil Engineering and Development Department San Tin / Lok Ma Chau Development Node Project Profile Final | May 2021 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements Ove Arup & Partners Hong Kong Ltd of our client. Level 5 Festival Walk It is not intended for and should not be 80 Tat Chee Avenue relied upon by any third party and no Kowloon Tong responsibility is undertaken to any third Kowloon party. Hong Kong www.arup.com Job number 271620 Civil Engineering and Development Department San Tin / Lok Ma Chau Development Node Project Profile Contents Page 1 Basic Information 3 1.1 Project Title 3 1.2 Purpose and Nature of Project 3 1.3 Name of Project Proponent 3 1.4 Location and Scale of Project and History of Site 3 1.5 Number and Types of Designated Projects to be Covered by the Project Profile 4 1.6 Name and Telephone Number of Contact Person 7 2 Outline of Planning and Implementation Programme 8 2.1 Project Implementation 8 2.2 Project Time Table 8 2.3 Interactions with Other Projects 8 3 Possible Impacts on the Environment 9 3.1 General 9 3.2 Air Quality 9 3.3 Noise 9 3.4 Water Quality 10 3.5 Waste Management 11 3.6 Land Contamination 11 3.7 Hazard to Life 11 3.8 Landfill Gas Hazard 12 3.9 Ecology 12 3.10 Agriculture and Fisheries 14 3.11 Cultural Heritage 14 3.12 Landscape and Visual 14 4 Major Elements of the Surrounding Environment 16 4.1 Surrounding Environment including Existing and Planned Sensitive Receivers 16 4.2 Air Quality 17 4.3 Noise 17 4.4 Water Quality 17 4.5 Waste Management 17 4.6 Land Contamination -

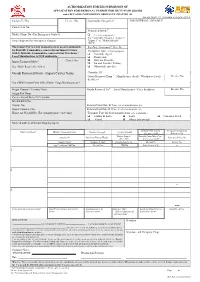

Authorization for Edi Submission of Dutiable Commodities Ordinance, Chapter

AUTHORIZATION FOR EDI SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION FOR REMOVAL PERMIT FOR DUTY-PAID GOODS under DUTIABLE COMMODITIES ORDINANCE, CHAPTER 109 (PLEASE COMPLETE THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTER) Contact Tel No. Licence No. Commodity Categories* FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Contact Fax No. Denatured Spirits # Mobile Phone No. (For Emergency Contact) ❑ Yes (tick as appropriate) (For Commodity Categories "Liquor 3", Email Address (For Emergency Contact) "Liquor 5"' or "Methyl Alcohol" ONLY) The Import Carrier info (located in Grey area) is applicable For Duty Assessment # Yes / No for Dutiable Commodities removed from Import Carrier Exemption Type : (tick as appropriate) ONLY, Dutiable Commodities removed from Warehouse / ❑ Consulate Agent Local Manufacturer is NOT applicable. ❑ Destruction ❑ Duty not Prescribe Import Transport Mode # Carrier No. ❑ Tar and Nicotine Testing Sea / Rail / Road / Air / Others ❑ Others (pls. specify) _______________________ Goods Removed From - Import Carrier Name Consulate ID Goods Removed From # – Manufacturer (local) / Warehouse (local) Licence No. & address Via (GBW/Control Point Office/Public Cargo Working area) * Origin Country / Territory Name Goods Removed To # – Local Manufacturer / Place & address Licence No. Origin Port Name Carrier Arrival Date (YYYY/MM/DD) BL/AWB/PO No. Voyage No. Removal Start Date & Time (YYYY/MM/DD HH24 : MI) Import Container No. Removal End Date & Time (YYYY/MM/DD HH24 : MI) House Air Waybill No. (For transport mode “Air” only) Transport Type for local transportation: (tick as appropriate) ❑ Lighter & Lorry ❑ Lorry ❑ Container Truck ❑ Vessel ❑ Others (pls specify) ___________________________ Name & address of Import Shipping Agent Dutiable Item Cost & Personal Consumption Marks of Goods Dutiable Commodity Code Declared Strength Sample Quantity Currency Code* Reference No. Return Sample Dutiable Item Other Cost Supplier No. -

For Discussion on 28 October 2008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL

For discussion on 28 October 2008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON DEVELOPMENT Development of Liantang/Heung Yuen Wai Boundary Control Point PURPOSE This paper briefs Members on the development of Liantang/Heung Yuen Wai boundary control point (LT/HYW BCP). BACKGROUND 2. On 27 May 2008, we briefed Members on the work of Hong Kong-Shenzhen (HK-SZ) Joint Task Force on Boundary District Development (港深邊界區發展聯合專責小組) (the JTF). Members were informed of the progress of two related planning studies on the proposed BCP at LT/HYW: the “SZ-HK Joint Preliminary Planning Study on Developing LT/HYW BCP” and the internal “Planning Study on LT/HYW BCP and Its Associated Connecting Roads in HK”. 3. Both studies were completed in June 2008. The HK Special Administrative Region Government (HKSARG) and the SZ Municipal People’s Government jointly announced the implementation of the new BCP after the second meeting of the JTF on 18 September 2008. Both sides will proceed with their detailed planning and design work with an aim to commence operation of the new BCP in 2018. A Working Group on Implementation of LT/HYW BCP (蓮塘/香園圍口岸工程實施工作小組) has been set up under the JTF to co-ordinate works of both sides. A LegCo brief summarizing the findings of the studies and scope of the new BCP development was issued on the announcement day (Appendix 1). 4. On the HK side, the development of LT/HYW BCP comprises the construction of a BCP with a footprint of about 18 hectares (including an integrated passenger clearance hall), a dual 2-lane trunk road of about 10 km in length, and improvement works to SZ River of about 4 km in length. -

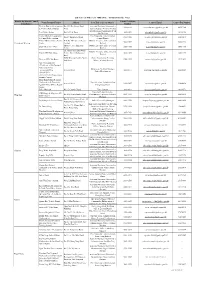

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 14-09-2020 and covers a total of 2773 related records from 07-09-2020 to 13-09-2020. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2020 年 9 月 14 日建立,包含從 2020 年 9 月 7 日到 2020 年 9 月 13 日到共 2773 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/ 註冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. 1 August 1996 Limited 0226988 08-09-2020 2. 123 Management Limited 123 管理有限公司 2975249 07-09-2020 3. 12F Studio Company Limited 12 樓工作室有限公司 2975397 07-09-2020 4. 1more Storm Limited 2975821 08-09-2020 5. 20 Two North Limited 2975101 07-09-2020 6. 22 CONSULTING SERVICES LIMITED 1464602 09-09-2020 7. 2pickss Limited 驛站自取點有限公司 2738276 08-09-2020 8. 2ZWEI SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT LIMITED 2976308 10-09-2020 9. 3A International Limited 2975426 07-09-2020 10. 6gNetworks Technology Co., Limited 2976682 10-09-2020 11. -

Shenzhen Shuttle Bus Service & Schedule

Shenzhen Shuttle Bus Service & Schedule Routing A) To and from Futian port and Shenfubao Building/Jiafu Plaza B) To and from Huanggang port and Shenfubao Building/Jiafu Plaza C) To and from Futian port and Animation City (Nanyou office) D) To and from Shenzhen Bay and Animation City (Nanyou office) E) To and from Shenfubao and Jiafu Plaza Pick up and drop off location Futian the parking lot for coaches at the adjacent corner of Gui Hua Road (桂花路) and Guo Hua Road (國花路) Huanggang Pick up point: Huanggang Coach Station(皇岗汽车站). The parking lot close to taxi stand Drop off point: Huanggang Customs Exit Hall Shenfubao Annex Bldg., Shenfubao Building, 8, Ronghua Road Jiafu Plaza Road side of Jiafu office main entrance Shenzhen Bay the parking lot for coaches towards the end of Shenzhen Bay exit Day of Service Monday to Friday (excludes China public holiday) Booking Not required. Services will be provided on a first come first serve basis. Arrangement - LiFung company logo will be shown on the shuttle bus - LiFung colleagues are requested to present staff card when boarding the shuttle Remarks - For enquiry of shuttle bus service, you may contact the following CS colleagues: Lucie Feng: 86 755 82856895 Kevin Long: 86 755 82856903 Photo of Shuttle Buses (Right side for Huanggang route only) Schedule Refer to the next 4 pages Route A1 - Futian Custom (Lok Ma Chau) → Shen Fu Bao → JiaFu Plaza (Every 10 minutes from 0830 to 1000) 0830 0920 0840 0930 0850 0940 0900 0950 0910 1000 Route A2 - Shen Fu Bao → JiaFu Plaza → Futian Custom (Lok Ma Chau) -

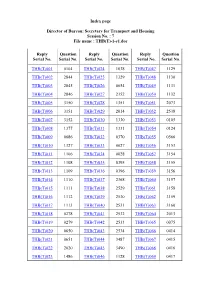

Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance Committee Members in Examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2012-13

Index page Director of Bureau: Secretary for Transport and Housing Session No. : 7 File name : THB(T)-1-e1.doc Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. THB(T)001 0104 THB(T)024 1038 THB(T)047 1129 THB(T)002 2844 THB(T)025 1329 THB(T)048 1130 THB(T)003 2845 THB(T)026 0654 THB(T)049 1131 THB(T)004 2846 THB(T)027 2352 THB(T)050 1132 THB(T)005 3150 THB(T)028 1351 THB(T)051 2073 THB(T)006 3151 THB(T)029 2014 THB(T)052 2538 THB(T)007 3152 THB(T)030 1330 THB(T)053 0105 THB(T)008 1377 THB(T)031 1331 THB(T)054 0124 THB(T)009 0686 THB(T)032 0370 THB(T)055 0566 THB(T)010 1327 THB(T)033 0027 THB(T)056 3153 THB(T)011 1106 THB(T)034 0028 THB(T)057 3154 THB(T)012 1108 THB(T)035 0395 THB(T)058 3155 THB(T)013 1109 THB(T)036 0396 THB(T)059 3156 THB(T)014 1110 THB(T)037 2368 THB(T)060 3157 THB(T)015 1111 THB(T)038 2529 THB(T)061 3158 THB(T)016 1112 THB(T)039 2530 THB(T)062 3159 THB(T)017 1113 THB(T)040 2531 THB(T)063 3160 THB(T)018 0278 THB(T)041 2532 THB(T)064 2013 THB(T)019 0279 THB(T)042 2533 THB(T)065 0075 THB(T)020 0650 THB(T)043 2534 THB(T)066 0414 THB(T)021 0651 THB(T)044 3487 THB(T)067 0415 THB(T)022 2020 THB(T)045 3490 THB(T)068 0416 THB(T)023 1486 THB(T)046 1128 THB(T)069 0417 Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. -

Invest Shenzhen Is the Organization Assigned by the Municipal Administration of Shenzhen Municipality

ABOUT US SHENZHENBASICS REFERENCES REVIEW AND APPROVAL SHENZHEN IN FOR COMPANY’S PROCEDURE MY EYES FOR FOREIGN-FUNDED OPERATION EXPENSES "Shenzhen is a clean and green city. The entire city’s layout and ENTERPRISES architecture really gives one a sense of design, and of obvious DONG GUAN energy and individuality. Shenzhen is a deeply memorable and moving city that is developing in a sustainable direction, and is one I’ll never forget. I’d like to give my most sincere well-wishes to the people of Shenzhen." GUANGMING HUI ZHOU 1 Prepare and submit materials according to the Foreign-funded Director-General of UNESCO Irina Bokova Enterprise Incorporation Instructions. RENT FOR OFFICE SPACE SALARY STANDARD "Is there another place like Shenzhen, a city that is a testament LONGGANG 2 Obtain approval of name from the Market Supervision to the importance of both building a road to sustainable BAO'AN LONGHUA IN KEY AREAS development and implementing structural reform? Through my Invest Shenzhen is the organization assigned by the municipal Administration of Shenzhen Municipality. PINGSHAN Average rent in Shenzhen’s Shenzhen’s minimum research of Shenzhen, I’ve discovered a string of processes and government with the task of attracting investment. Invest achievements that showcase the Municipality’s striking economic INVEST Grade A office buildings salary performance." Shenzhen’s tasks are to promote and consolidate Shenzhen’s 3 Pass review and approval by the Economy, Trade and Information Chairman of the World Free Zone Convention investment environment and business advantages, and the agency Commission of Shenzhen Municipality or by the economic Graham Mather DAPENG is committed to bringing in investment projects and teams of 2 promotion (service) bureau of each district, and acquire approval YANTIAN /m / Month talented professionals that match the city’s positioning and industry NANSHAN ¥ 215 ¥ 2,030 and issuance of the Foreign Invested Enterprise Approval "Each day seems to bring something new for Shenzhen’s reform, development, and city building. -

Hong Kong's Economy Hong Kong's

Issue: Hong Kong’s Economy Hong Kong’s Economy By: Suzanne Sataline Pub. Date: January 15, 2018 Access Date: September 28, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/237455680403.n1 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1946-105183-2873883/20180115/hong-kongs-economy ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Can it regain its luster? Executive Summary Hong Kong provided much of the economic muscle that has transformed China into a global financial powerhouse over the past three decades. The city of 7.3 million, which has been a special administrative region of China since the United Kingdom relinquished control in 1997, is increasingly intertwined with the mainland. But while Hong Kong remains relatively prosperous and is still a regional financial center, its recent growth rate is well below that of the People’s Republic. The territory has failed to diversify to mitigate its reliance on trade services and finance and faces a host of problems that will be difficult to overcome, according to economic experts. “Hong Kong has gone sideways,” says one. Key takeaways include: Hong Kong’s economic growth rate has fallen from more than 7 percent in the 1980s to about half of that late last year, while China has expanded to become the world’s second largest economy. China now accounts for more than half of Hong Kong’s goods exports and 40 percent of its service exports. Hong Kong was the world’s busiest port in 2004; it has since slipped to number five while Shanghai has moved into the top spot. -

Sonneratia Apetala and S

Copyright Warning Use of this thesis/dissertation/project is for the purpose of private study or scholarly research only. Users must comply with the Copyright Ordinance. Anyone who consults this thesis/dissertation/project is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no part of it may be reproduced without the author’s prior written consent. THE DISTRIBUTION, ECOLOGY, POTENTIAL IMPACTS AND MANAGEMENT OF EXOTIC PLANTS, Sonneratia apetala AND S. caseolaris, IN HONG KONG MANGROVES TANG WING SZE MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SEPTEMBER 2009 CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG 香港城市大學 The Distribution, Ecology, Potential Impacts and Management of Exotic Plants, Sonneratia apetala and S. caseolaris, in Hong Kong Mangroves 香港外來的紅樹林植物―無瓣海桑及海桑 的分布、生態、潛在影響及其管理 Submitted to Department of Biology and Chemistry 生物及化學系 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy 哲學碩士學位 by Tang Wing Sze 鄧詠詩 September 2009 二零零九年九月 i Declaration I declare that this thesis represents my own work, except, where due acknowledgement is given, and that it has not been previously included in a thesis, dissertation or report submitted to this University or to any other institution for a degree, diploma or other qualification Signed:___________________________ Tang Wing-sze ii Abstract of thesis entitled The Distribution, Ecology, Potential Impacts and Management of Exotic Plants, Sonneratia apetala and S. caseolaris, in Hong Kong Mangroves submitted by Tang Wing Sze for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the City University of Hong Kong in September 2009 Invasion is now considered as a global threat to biodiversity as it is more pervasive than loss of natural habitats and anthropogenic pollution. -

Palaeozoic Rocks of the San Tin Group Classification and Distribution

PalaeozoicRocks of the San Tin Group Classification and Distribution The sedimenmryrocks of this Palaeozoicbasin (the San Tin Group) occupy a northeasterly,curving, faulted, irregular belt at least 25 km long and up to a maximum of 4 km in width. This fault-bounded basinextends northwards into Shenzhenand Guangdong,and south throughTuen Mun. Bennett (1984c) outlined the basic structureof the areaas a narrow grabenbetween the CastlePeak and the Sung Kong granites,and noted the presenceof metasedimenmryrocks of the Repulse Bay Formation and the Lok Ma ChauFormation. The San Tin Group is divided into two formations; a lower, largely calcareousYuen Long Formation, and an upper, mostly arenaceous/argillaceousLok Ma ChauFormation (Langford et ai, 1989)(Figure5). Yuen Long Formation The Yuen Long Fonnation was named by Lee (1985) to distinguish the concealed marbles and limestonesof the Yuen Long area from the better known clastic rocks belonging to the establishedand exposed Lok Ma Chau Fonnation (Bennett, 1984b). The distinctive carbonate lithologies were originally recognised by Ha et al (1981), who suggested that they probably belonged to the CarboniferousPeriod. General supportfor a Carboniferousage was provided by the strike of the rocks which could be traced northeastwardsinto Shenzhen,where unpublished1:50 000 geologicalmapping of the Shenzhen,Special Economic Zone apparently showed similar lithologies classified as Lower Carboniferous(Visean) (Lai & Mui, 1985). The Yuen Long Fonnation is overlain by the Lok Ma Chau Fonnation. The boundary betweenthe two fonnations is in places gradationalbut in others sharp and probably unconfonnable.The presenceof beds of marble intercalatedwith the lowest metasiltstonesin someboreholes is interpretedby Langford et al (1989) to be a gradual passagefrom a dominantly calcareoussequence to one of largely clastic material.