The Constitutionality of Faith-Based Prison Programs: a Real World Analysis Based in New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREA) Audit Report Adult Prisons & Jails

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Audit Report Adult Prisons & Jails ☐ Interim ☒ Final Date of Report January 15, 2021 Auditor Information Name: Darla P. O’Connor Email: [email protected] Company Name: PREA Auditors of America Mailing Address: 14506 Lakeside View Way City, State, Zip: Cypress, TX Telephone: 225-302-0766 Date of Facility Visit: December 1-2, 2020 Agency Information Name of Agency: Governing Authority or Parent Agency (If Applicable): Texas Department of Criminal Justice State of Texas Physical Address: 861-B I-45 North City, State, Zip: Huntsville, Texas 77320 Mailing Address: PO Box 99 City, State, Zip: Huntsville, Texas 77342 The Agency Is: ☐ Military ☐ Private for Profit ☐ Private not for Profit ☐ Municipal ☐ County ☒ State ☐ Federal Agency Website with PREA Information: https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/tbcj/prea.html Agency Chief Executive Officer Name: Bryan Collier Email: [email protected] Telephone: 936-437-2101 Agency-Wide PREA Coordinator Name: Cassandra McGilbra Email: [email protected] Telephone: 936-437-5570 PREA Coordinator Reports to: Number of Compliance Managers who report to the PREA Coordinator Honorable Patrick O’Daniel, TBCJ Chair 6 PREA Audit Report – V5. Page 1 of 189 Jester Complex, Richmond, TX Facility Information Name of Facility: Jester Complex Physical Address: 3 Jester Road City, State, Zip: Richmond, TX 77406 Mailing Address (if different from above): Jester 2 (Vance) 2 Jester Road City, State, Zip: Richmond, TX 77406 The Facility Is: ☐ Military ☐ Private for Profit ☐ Private not for Profit ☐ Municipal ☐ County ☒ State ☐ Federal Facility Type: ☒ Prison ☐ Jail Facility Website with PREA Information: https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/tbcj/prea.html Has the facility been accredited within the past 3 years? ☒ Yes ☐ No If the facility has been accredited within the past 3 years, select the accrediting organization(s) – select all that apply (N/A if the facility has not been accredited within the past 3 years): ☒ ACA ☐ NCCHC ☐ CALEA ☐ Other (please name or describe: Click or tap here to enter text. -

Judge's Guide to Handling Cases Involving Persons with Mental Disorders

JUDGE’S GUIDE TO HANDLING CASES INVOLVING PERSONS WITH MENTAL DISORDERS JUDGES GUIDE: Handling Cases Involving Persons with Mental Disorders Prepared By: Stephanie Rhoades District Court Judge Alaska Court System [email protected] Colleen Ray Committing Magistrate/Master Alaska Court System [email protected] Edited By: Mary “Meg” Greene Senior Superior Court Judge Alaska Court System [email protected] Administrative Support Jennie Marshall-Hoenack [email protected] July 2008 Judges’ Guide: Handling Cases Involving Persons with Mental Disorders ___________________________________________________________________________________ JUDGE’S GUIDE TO HANDLING CASES INVOLVING PERSONS WITH MENTAL DISORDERS TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I. COMPETENCY FOR LEGAL PROCEEDINGS 1. Competency for Legal Proceedings Flowchart 2. Competency – First Evidentiary Hearing 3. Competency –Second Evidentiary Hearing 4. Competency - Third Evidentiary Hearing 5. Competency—Final Hearing 6. Forms: CR260 Order for Psychiatric Examination CR265 Order of Commitment and Transport 7. Juvenile Delinquency—Order for Competency Evaluation 8. Mental Health Evaluations: Guidelines for Judges and Attorneys 9. Court-ordered Medication for Competency 10. Harvard Law Review Excerpt PART II. INVOLUNTARY COMMITMENT 11. Emergency Initiation of Commitment (out of court) 12. Non-Emergency Initiation and Hearing 13. 30-Day Commitment Hearing 14. 90-Day Commitment Hearing 15. 180-Day Commitment Hearing 16. Hearing on Involuntary Administration of Medication 17. Appendix 1 Mentally, Gravely Disabled, Danger to Self or Others 18. Appendix 2 Notice 19. Appendix 3 Rights 20. Appendix 4 No Less Restrictive Alternative 21. Appendix 5 Finding Placement at Closest Facility 22. Appendix 6 Mental Commitment Forms 23. Appendix 7 Ability to Give and Withhold Consent 24. -

Adult Correctional Systems

ADULT CORRECTIONAL SYSTEMS A Report Submitted to the FISCAL AFFAIRS AND GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS COMMITTEE Southern Legislative Conference Council of State Governments John D. Carpenter John A. Alario, Jr., President Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Officer Louisiana Senate Prepared by: Taylor F. Barras, Speaker Monique Appeaning Louisiana House of Representatives Fiscal Analyst/Special Projects Coordinator Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Office 2017 This public document was published at a total cost of $ 2QH KXQGUHG 10 copies of this public document were published in this firstprintingDWDFRVWRI.ThHWRWDOFRVWRIDOOSULQWLQJVRIWKLVdocumentLQFOXGLQJUHSULQWVLV7KLVGRFXPHQWwaspublishedby OTS-PURGXFWLRQSXSSRUWSHUYLFHV,627North4thStreet,BatonRouge,LA70802fortheLouisianaLegislativeFiscalOfficeinanefforttoprovide legislators, staff and the general public with an accurate summary ofAdult Correctional SystemsComparativeDataforFY17. Thismaterial wasprintedinaccordancewith thestandards forprinting bystate agenciesestablished pursuantto R.S.43.31.Printing of this material was purchased in accordance with the provisions of Title 43 of the Louisiana Revised Statutes. ADULT CORRECTIONAL SYSTEMS TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Introduction and Methodology I. Inmate Population Trends and Incarceration Rates 10 - 15 II. Prison and Jail Capacities 16 - 25 III. Budgetary Issues 26 - 30 IV. Staffing Patterns and Select Inmate Characteristics 31 - 41 V. Projected Costs of New Prisons 42 - 44 VI. Probation and Parole 45 - 50 VII. Rehabilitation 51 - 53 VIII. Prison Industries -

Texas Department of Criminal Justice

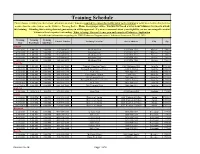

VOLUNTEER TRAINING SCHEDULE Please choose a training site that is most convenient to attend. You are required to contact the facility prior to the training to verify no schedule changes have occurred and to ensure you are on the Volunteer Training Roster. Please wear proper attire. You DO NOT need a letter from Volunteer Services to attend this training. Attending this training does not guarantee you will be approved. If you are concerned about your eligibility you are encouraged to contact Volunteer Services prior to attending. What to Bring: driver’s license, pen, completed Volunteer application For additional information regarding the TDCJ Volunteer Program contact Volunteer Services at 936-437-3026 ABILENE, TEXAS AUSTIN, TEXAS McConnell Unit BRYAN, TEXAS Middleton Transfer Facility Diocese of Austin Pastoral 3001 S. Emily Drive Hamilton Unit Visitation Room Center Beeville, TX 78102 PRTC Bldg. Room 119 13055 FM 3522 6225 Highway 290 E (361) 362-2300 200 Lee Morrison Lane Abilene, TX 79601 Austin, TX 78723 01/21/16 9:00am – 1:00pm Bryan, TX 77807 (325) 548-9075 (512) 926-4482 04/21/16 9:00am – 1:00pm (979) 779-1633 05/14/16 1:00pm – 5:00pm 01/09/16 12:00pm – 4:00pm 07/21/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 03/05/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 08/20/16 1:00pm – 5:00pm 04/09/16 12:00pm – 4:00pm 10/20/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 06/04/16 9:00am – 1:00pm 11/19/16 1:00pm – 5:00pm 07/16/16 12:00pm – 4:00pm 09/03/16 9:00am – 1:00pm BONHAM, TEXAS 12/03/16 9:00am – 1:00pm Robertson Unit St. -

2017 Leadership Book

“Seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you…because if it prospers, you too will prosper” Jeremiah 29:7 2017 LEADERSHIP BOOK ANNUAL CHURCH CONFERENCE REPORT NOVEMBER 13, 2016 The Reverend Jay Jackson, Superintendent, Southwest District The Texas Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church C. Chappell Temple, Dan Conway, Michelle Hall, Mike Whang Christ Church Pastoral Staff With thanks to SugarLand.com for images of Sugar Land, Texas. 2 christchurchsl.org 3 Welcome from our Pastors There are many words and expressions in our culture that bid welcome. My offering to you would be “thank you for saying yes to God and Christ Church and know that It’s a greeting used by everyone these days, from Muslims who say, “As-salamu alaykum” (or you are so welcome. My hope for each person/family is that they would experience “peace be upon you”) to Hebrews who start each Friday with “Shabbat Shalom” (“peaceful the inestimable love of Jesus Christ and find your place among us. If I could sing, Sabbath”) to even those stuck in the Sixties who may tell you when leaving somewhere simply and those who know me would confirm that I can NOT, I would sing “Oh How I Love “Peace Out!” For in truth, there is nothing more satisfying to many than to enjoy peace in their Jesus”. Please know that your pastor, Michelle, is imperfect, but by the grace of God, I lives, one way or the other. continue to trust that if I live as faithfully as I can, He will continue to lead and guide me. -

2019 Adult Correctional Systems Survey

ADULT CORRECTIONAL SYSTEMS A Report Submitted to the FISCAL AFFAIRS AND GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS COMMITTEE Southern Legislative Conference Council of State Governments Prepared by: Patrick Page Cortez, President Monique Appeaning Louisiana Senate Fiscal Analyst/Special Projects Coordinator Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Office Clay Schexnayder, Speaker Christopher Keaton Louisiana House of Representatives Legislative Fiscal Officer 2019 This public document was published at a total cost of $813.98 ($10.85 per copy). 75 copies of this public document were published in this first printing. The total cost of all printings of this document including reprints is $813.98. This document was published by OTS-PSS, 627 North 4th Street, Baton Rouge, LA 70802 for the Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Office, Post Office Box 44097, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70804 in an effort to provide legislators, staff and the general public with an accurate summary of Adult Correctional Systems Comparative Data for FY 19. This material was printed in accordance with the standards for printing by state agencies established pursuant to R.S. 43.31. Printing of this material was purchased in accordance with the provisions of Title 43 of the Louisiana Revised Statutes. ADULT CORRECTIONAL SYSTEMS TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Introduction and Methodology I. Inmate Population Trends and Incarceration Rates ...………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 - 15 II. Prison and Jail Capacities ......…….....…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….................16 -

Training Schedule (Revised Date - 01/03/2019)

Training Schedule (Revised Date - 01/03/2019) Please choose a training site that is most convenient to attend. You are required to contact the facility prior to the training to verify no schedule changes have occurred and to ensure you are on the Volunteer Training Roster. Please wear proper attire. You DO NOT need a letter from Volunteer Services to attend this training. Attending this training does not guarantee you will be approved. If you are concerned about your eligibility you are encouraged to contact Volunteer Services prior to attending. What to bring: Drivers License, pen and completed Volunteer Application. For additional information regarding the TDCJ Volunteer Program contact Volunteer Services at 936-437-3026. Training Start Training End Training Date Contact Number Training Location Street Address City Zip Time Time Abilene 4/20/2019 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9035 Robertson unit 12071 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 6/15/2019 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9075 Middleton Unit 13055 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 8/17/2019 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9035 Robertson unit 12071 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 12/7/2019 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9075 Middleton Unit 13055 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 Amarillo 1/19/2019 9:00 AM 1:00 PM 806-381-7080 Trinity Fellowship Church 5000 Hollywood Rd Amarillo 79118 3/28/2019 10:00 AM 1:00 PM 806-381-7080 Bishop Defalco Retreat Center 2100 N. Spring Amarillo 79107 4/10/2019 10:00 AM 2:00 PM 806-381-7080 Bishop Defalco Retreat Center 2100 N. -

2015 Summer Newsletter.Pub

God’s Special Time Summer 2015 News from Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc. Vol. 41 No. 2 Kairos Gears Up for the 2015 Annual Conference Excitement is building for the that this theme along with Mr. Bell chairs the Health Care 2015 Kairos Prison Ministry corresponding Bible verses, will Committee and is a member of the International Annual Conference. be incorporated throughout the Audit and Review and Business & The conference will be held at the entire conference, including Financial Operations committees. American Airline Training and meetings, workshops, general He is the Chairman/CEO and Conference Center in Fort Worth, sessions, etc. founder of Oliver J. Texas July 28 through August 1st. Bell, Inc., and the We are excited to Chairman/founder of This year Kairos moved from a announce that Oliver J. the Texas Labor & Winter and Summer conference Bell, Chairman or the Employee Relations to just one annual conference to Texas Board of Criminal Consortium. be held during the summer Justice, will be our keynote months. Hopefully, this will speaker for the Friday This year we have encourage states and countries to evening general session put together a new provide for more of their following the banquet. set of Workshops for volunteers to attend. So far, our volunteers to registrations are up over previous Oliver Bell was appointed to the attend. We feel honored with the years, with many states having Texas Board of Criminal Justice assemblage of presenters and the already registered their state and in February 2004 and was outstanding workshop content that Advisory Council members. reappointed in 2009. -

Service of Holy Eucharist Holy Baptism and Confirmation the 17Th Sunday After Pentecost-Proper 22

Service of Holy Eucharist Holy Baptism and Confirmation The 17th Sunday after Pentecost-Proper 22 October 6, 2019 8:00 AM The Rt. Rev. Kathryn Ryan Bishop Suffragan in the Diocese of Texas Calvary Episcopal Church 806 Thompson Road Richmond, TX 77469 www.calvaryrichmond.org The Rev. Lecia Brannon, Locum Tenens The Rev. Nancy Wilkes, Deacon Holy Eucharist - Rite I 8:00 AM The Word of God (B.C.P., PG. 323) Processional Hymn COME, LABOR ON Hymn # 541 The people standing, the Presider says Blessed be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. People And blessed be his kingdom, now and for ever. Amen. The Presider continues Almighty God, unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen. Hear what our Lord Jesus Christ saith: Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets. GLORIA Hymn # S-280 Glory to God in the highest, and peace to his people on earth. Lord God, heavenly King, almighty God and Father, we worship you, we give you thanks, we praise you for your glory. Lord Jesus Christ, only Son of the Father, Lord God, Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world; have mercy on us; you are seated at the right hand of the Father; receive our prayer. -

What Is Prisoner Reentry?

Outside the Walls: A National Snapshot of Community-Based Prisoner Reentry Programs Table of Contents List of Sample Programs......................................................................................................................4 Project Overview.................................................................................................................................7 Reentry Television Documentaries ....................................................................................................9 What Is Prisoner Reentry? .................................................................................................................12 Education & Employment and Reentry: Briefing Paper .................................................................13 Education & Employment and Reentry: Programs.........................................................................17 Health Challenges of Reentry: Briefing Paper ................................................................................49 Health Challenges of Reentry: Programs ........................................................................................56 Housing and Reentry: Briefing Paper ..............................................................................................81 Housing and Reentry: Programs ......................................................................................................84 Family and Reentry: Briefing Paper ...............................................................................................102 -

Winter 2008 News from Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc

God’s Special Time Winter 2008 News from Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc. Vol. 34, No.2 Christmas 2008 New Year 2009 Something to Contemplate this Holiday Season…………. Matthew 25:37-46 "Then the prison, and did not help you?' time. Right on baby, we don't righteous will answer him, 'Lord, "He will reply, 'I tell you the have time for people who break when did we see you hungry and truth, whatever you did not do God's laws and sin in God's feed you, or thirsty and give you for one of the least face, do we? something to drink? When did of these, you did we see you a stranger and invite not do for me.' God didn't really mean that you in or needing clothes and those who don't see and hear clothe you? When did we see "Then they will go away to eter- and seek would be cast out, you sick or in prison and go to nal punishment, but the righteous does He? I never broke any visit you?' to eternal life." laws or sinned or needed for- giveness so why should I spend "The King will reply, 'I tell you Are you familiar with this? my time and hard earned money the truth, whatever you did for There it is as plain as the nose on on a bunch like those guys and one of the least of these brothers your face. Jesus telling all when gals in prison? of mine, you did for me.' "Then we see the sick, hungry, thirsty, he will say to those on his left, in need of clothing, or in prison, Maybe God isn't asking you to 'Depart from me, you who are we are called to do something go behind the walls, or even cursed, into the eternal fire pre- more than ignore them. -

Training Schedule Please Choose a Training Site That Is Most Convenient to Attend

Training Schedule Please choose a training site that is most convenient to attend. You are required to contact the facility prior to the training to verify no schedule changes have occurred and to ensure you are on the Volunteer Training Roster. Please wear proper attire. You DO NOT need a letter from Volunteer Services to attend this training. Attending this training does not guarantee you will be approved. If you are concerned about your eligibility you are encouraged to contact Volunteer Services prior to attending. What to bring: Drivers License, pen and completed Volunteer Application. For additional information regarding the TDCJ Volunteer Program contact Volunteer Services at 936-437-3026. Training Training Training Contact Number Training Location Street Address City Zip Date Start Time End Time Abilene 12/9/2017 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9075 Middleton Unit 13055 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 4/21/2018 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9035 Robertson unit 12071 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 6/16/2018 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9075 Middleton Unit 12071 FM 3522 Abilene 70601 8/18/2018 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9035 Robertson Unit 12071 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 12/8/2018 1:00 PM 5:00 PM 325-548-9075 Middleton Unit 12071 FM 3522 Abilene 79601 Amarillo 1/20/2018 9:00 AM 1:00 PM 806-381-7080 Trinity Fellowship Church 5000 Hollywood Rd. Amarillo 79118 3/29/2018 10:00 AM 2:00 PM 806-381-7080 Bishop DeFalco Retreat Center 2100 N.