Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Departmental Performance Report 2009-2010

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Departmental Performance Report 2009-2010 The Honourable Vic Toews, P.C., Q.C., M.P. Minister of Public Safety 1 2 Table of ConTenTs Minister’s Message ..............................................................................................................................................5 section I: Departmental overview .....................................................................................................................7 Raison d’être ....................................................................................................................................................7 Responsibilities .................................................................................................................................................7 Strategic Outcomes and Program Activity Architecture ........................................................................................7 Summary of Performance ..................................................................................................................................7 Contribution of Priorities to Strategic Outcomes ..................................................................................................9 Operational Priorities ......................................................................................................................................11 Management Priorities ....................................................................................................................................12 -

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service: Squaring the Demands of National Security with Canadian Democracy* by Gerard F

Conflict Quarterly The Canadian Security Intelligence Service: Squaring the Demands of National Security with Canadian Democracy* by Gerard F. Rutan Political truth is always precious in a democracy for it always makes up the first element of justice. Political truth is always suspect in a dictatorship, for it usually makes up the first element of treason. Anon. INTRODUCTION This article is historical in methodology, descriptive/analytic in focus. It was written to offer a primarily European readership an understanding of the origins, development, structure, and functions of the new Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). Canadians who are, naturally, more familiar with the history and building of the CSIS will find it somewhat basic. Persons knowledgeable in security in telligence affairs will find little new or exciting in it. Yet, it is important that this case study of how a democratic state faced a scandal in its security intelligence functions, and came out of the scandal with a new, legal and democratic security intelligence process, be examined and ex plained. There are few state systems on earth today which have had the ability and the political will to do what Canada did: to confront an in telligence/security scandal and turn it into a strengthening of democracy. The Commission of Inquiry Concerning Certain Activities of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, more popularly known as the McDonald Commission, was established in July 1977. The proximate cause for its establishment was an official statement by the then Commis sioner of the RCMP that allegations of participation by the force in il legal acts (including the break-in at a Quebec press agency office) might have some basis in fact.1 The Commission acknowledged that some members of the force might have been using methods and procedures not sanctioned by law in the performance of their duties for some time, par ticularly those duties associated with national defense and counteres pionage or counter-terrorism. -

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

The Search for Continental Security

THE SEARCH FOR CONTINENTAL SECURITY: The Development of the North American Air Defence System, 1949 to 1956 By MATTHEW PAUL TRUDGEN A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 12, 2011 Copyright © Matthew Paul Trudgen, 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the development of the North American air defence system from the beginning of the Cold War until 1956. It focuses on the political and diplomatic dynamics behind the emergence of these defences, which included several radar lines such as the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line as well as a number of initiatives to enhance co-operation between the United States Air Force (USAF) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). This thesis argues that these measures were shaped by two historical factors. The first was several different conceptions of what policy on air defence best served the Canadian national interest held by the Cabinet, the Department of External Affairs, the RCAF and the Other Government Departments (OGDs), namely Transport, Defence Production and Northern Affairs. For the Cabinet and External Affairs, their approach to air defence was motivated by the need to balance working with the Americans to defend the continent with the avoidance of any political fallout that would endanger the government‘s chance of reelection. Nationalist sentiments and the desire to ensure that Canada both benefited from these projects and that its sovereignty in the Arctic was protected further influenced these two groups. On the other hand, the RCAF was driven by a more functional approach to this issue, as they sought to work with the USAF to develop the best air defence system possible. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

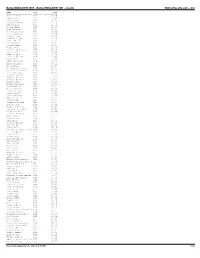

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

Vancouver Institute: an Experiment in Public Education

1 2 The Vancouver Institute: An Experiment in Public Education edited by Peter N. Nemetz JBA Press University of British Columbia Vancouver, B.C. Canada V6T 1Z2 1998 3 To my parents, Bel Newman Nemetz, B.A., L.L.D., 1915-1991 (Pro- gram Chairman, The Vancouver Institute, 1973-1990) and Nathan T. Nemetz, C.C., O.B.C., Q.C., B.A., L.L.D., 1913-1997 (President, The Vancouver Institute, 1960-61), lifelong adherents to Albert Einstein’s Credo: “The striving after knowledge for its own sake, the love of justice verging on fanaticism, and the quest for personal in- dependence ...”. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: 9 Peter N. Nemetz The Vancouver Institute: An Experiment in Public Education 1. Professor Carol Shields, O.C., Writer, Winnipeg 36 MAKING WORDS / FINDING STORIES 2. Professor Stanley Coren, Department of Psychology, UBC 54 DOGS AND PEOPLE: THE HISTORY AND PSYCHOLOGY OF A RELATIONSHIP 3. Professor Wayson Choy, Author and Novelist, Toronto 92 THE IMPORTANCE OF STORY: THE HUNGER FOR PERSONAL NARRATIVE 4. Professor Heribert Adam, Department of Sociology and 108 Anthropology, Simon Fraser University CONTRADICTIONS OF LIBERATION: TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION IN SOUTH AFRICA 5. Professor Harry Arthurs, O.C., Faculty of Law, Osgoode 132 Hall, York University GLOBALIZATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS 6. Professor David Kennedy, Department of History, 154 Stanford University IMMIGRATION: WHAT THE U.S. CAN LEARN FROM CANADA 7. Professor Larry Cuban, School of Education, Stanford 172 University WHAT ARE GOOD SCHOOLS, AND WHY ARE THEY SO HARD TO GET? 5 8. Mr. William Thorsell, Editor-in-Chief, The Globe and 192 Mail GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS: POWER IN CANADIAN MEDIA AND POLITICS 9. -

The Influence of Political Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1977 The Influence of oliticalP Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia Henrik J. von Winthus Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation von Winthus, Henrik J., "The Influence of oliticalP Leaders on the Provincial Performance of the Liberal Party in British Columbia" (1977). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1432. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1432 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF POLITICAL LEADERS ON THE PROVINCIAL PERFORMANCE OF THE LIBERAL PARTY IN BRITISH COLUMBIA By Henrik J. von Winthus ABSTRACT This thesis examines the development of Liberalism In British Columbia from the aspect of leader influence. It intends to verify the hypothesis that in the formative period of provincial politics in British Columbia (1871-1941) the average voter was more leader- oriented than party-oriented. The method of inquiry is predominantly historical. In chronological sequence the body of the thesis describes British Columbia's political history from 1871, when the province entered Canadian confederation, to the resignation of premier Thomas Dufferin Pattullo, in 1941. The incision was made at this point, because the following eleven year coalition period would not yield data relevant to the hypothesis. Implicitly, the performance of political leaders has also been evaluated in the light of Aristotelian expectations of the 'zoon politikon'. -

Paul J. Lawrence Fonds PF39

FINDING AID FOR Paul J. Lawrence fonds PF39 User-Friendly Archival Software Tools provided by v1.1 Summary The "Paul J. Lawrence fonds" Fonds contains: 0 Subgroups or Sous-fonds 4 Series 0 Sub-series 0 Sub-sub-series 2289 Files 0 File parts 40 Items 0 Components Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................Biographical/Sketch/Administrative History .........................................................................................................................54 .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................................Scope and Content .........................................................................................................................54 ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc.