MOVING on in MISSION and MINISTRY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property Owner's List (As of 10/26/2020)

Property Owner's List (As of 10/26/2020) MAP/LOT OWNER ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE PROP LOCATION I01/ 1/ / / LEAVITT, DONALD M & PAINE, TODD S 828 PARK AV BALTIMORE MD 21201 55 PINE ISLAND I01/ 1/A / / YOUNG, PAUL F TRUST; YOUNG, RUTH C TRUST 14 MITCHELL LN HANOVER NH 03755 54 PINE ISLAND I01/ 2/ / / YOUNG, PAUL F TRUST; YOUNG, RUTH C TRUST 14 MITCHELL LN HANOVER NH 03755 51 PINE ISLAND I01/ 3/ / / YOUNG, CHARLES FAMILY TRUST 401 STATE ST UNIT M501 PORTSMOUTH NH 03801 49 PINE ISLAND I01/ 4/ / / SALZMAN FAMILY REALTY TRUST 45-B GREEN ST JAMAICA PLAIN MA 02130 46 PINE ISLAND I01/ 5/ / / STONE FAMILY TRUST 36 VILLAGE RD APT 506 MIDDLETON MA 01949 43 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/ / / VASSOS, DOUGLAS K & HOPE-CONSTANCE 220 LOWELL RD WELLESLEY HILLS MA 02481-2609 41 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/A / / VASSOS, DOUGLAS K & HOPE-CONSTANCE 220 LOWELL RD WELLESLEY HILLS MA 02481-2609 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/B / / KERNER, GERALD 317 W 77TH ST NEW YORK NY 10024-6860 38 PINE ISLAND I01/ 7/ / / KERNER, LOUISE G 317 W 77TH ST NEW YORK NY 10024-6860 36 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/A / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 23 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/B / / MCCUNE, STEVEN; MCCUNE, HENRY CRANE; 5 EMERY RD SALEM NH 03079 26 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/C / / MCCUNE, STEVEN; MCCUNE, HENRY CRANE; 5 EMERY RD SALEM NH 03079 33 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/ / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 21 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/A / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 17 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/B / / FLYNN, MICHAEL P & LOUISE E 16 PINE ISLAND MEREDITH NH -

R,Eg En T's S.10411415 Wood -P P

R,EG EN T'S S.10411415 WOOD -P P o AAYLLOONt \\''. 4k( ?(' 41110ADCASTI -PADDINGTON "9' \ \ - s. www.americanradiohistory.com St l'ANCRAS U S TON \ 4\ \-4 A D RUSSEL. A. 'G,PORTLAND St \ O \ \ L. \ \2\\\ \ SQUARE \ l' \ t' GOO DGT. 1,..\ S , ss \ ' 11 \ \ \ 4-10USi \ç\\ NV cY\6 \ \ \ e \ """i \ .jP / / ert TOTT E N NAM // / ;COI COURT N.O. \ ON D ).7"'";' ,sr. \,60 \-:Z \COvtroi\ oA ARDEN O \ www.americanradiohistory.com X- www.americanradiohistory.com THE B. B. C. YEAR=BOOK 1 93 3 The Programme Year covered by this book is from November I, 1931 to October 31, 1932 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION BROADCASTING HOUSE LONDON W I www.americanradiohistory.com f Readers unfamiliar with broadcasting will find it easier to understand the articles in this book if they bear in mind the following :- (I) The words "Simultaneous(ly) Broadcast" or "S.B." refer to the linking of two or more transmitters by telephone lines for the purpose of broadcasting the same programme ; e.g. the News Bulletins are S.B. from all B.B.C. Stations. (2) The words "Outside Broadcast" or "O.B." refer to a broadcast outside the B.B.C. studios, not necessarily out -of- doors; e.g. a concert in the Queen's Hall or the commentary on the Derby are equally outside broadcasts. (3) The B.B.C. organisation consists, roughly speaking, of a Head Office and five provincial Regions- Midland Region, North Region, Scottish Region, West Region, and Belfast. The Head Office includes the administration of a sixth Region - the London Region-which supplies the National programme as well as the London Regional programme. -

Bishop of Ebbsfleet

THE SEE OF EBBSFLEET where St Augustine of Canterbury first landed and preached in 597 MONTHLY INTERCESSION SCHEME 2014 “Beloved, let us hold fast to the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who has promised is faithful. And let us consider how to provoke one another to love and good deeds, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day approaching.” Hebrews 10.23-25 DAY 1 For Bishop JONATHAN and Sarah his wife DAY 2 For The Diocese of DERBY St Anne, Derby: Vacant, Canon Michael Brinkworth St Luke, Derby: Vacant, Fr Theodore Holmes St Bartholomew, Derby: Vacant, Fr Theodore Holmes St Francis, Mackworth: Vacant, Fr Theodore Holmes St Thomas, Somercotes: Fr Peter Davies St Laurence, Long Eaton and Holy Trinity, Ilkeston: Bishop Roger Jupp St John the Baptist, Staveley, with St Columba, Inkersall, and St Andrew, Barrow Hill: Fr Stephen Jones, Fr David Teasdel, Fr Derek Booth, Fr Ian Falconer, Fr Brian Hoskin St Paul, Hasland, & St James, Temple Normanton: Fr Malcolm Ainscough, Fr John Butterfield DAY 3 For Fr William Butt, the Bishop’s Representative for Derby Clergy and People in Non-Petitioning Parishes in Derby DAY 4 For Archbishop Justin Welby and Archbishop John Sentamu, the College of Bishops and the General Synod. For the Council of Bishops of The Society [http://www.sswsh.com/bishops.php] DAY 5 For The Diocese of LICHFIELD - Stafford area Christ Church, Tunstall with St John, Goldenhill: Fr John Stather St Saviour, Smallthorne: Fr Richard Grigson, -

This 2008 Letter

The Most Reverend and Right Hon the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury & The Most Reverend and Right Hon the Lord Archbishop of York July, 2008 Most Reverend Fathers in God, We write as bishops, priests and deacons of the Provinces of Canterbury and York, who have sought, by God’s grace, in our various ministries, to celebrate the Sacraments and preach the Word faithfully; to form, nurture and catechise new Christians; to pastor the people of God entrusted to our care; and, through the work of our dioceses, parishes and institutions, to build up the Kingdom and to further God’s mission to the world in this land. Our theological convictions, grounded in obedience to Scripture and Tradition, and attentive to the need to discern the mind of the whole Church Catholic in matters touching on Faith and Order, lead us to doubt the sacramental ministry of those women ordained to the priesthood by the Church of England since 1994. Having said that, we have engaged with the life of the Church of England in a myriad of ways, nationally and locally, and have made sincere efforts to work courteously and carefully with those with whom we disagree. In the midst of this disagreement over Holy Order, we have, we believe, borne particular witness to the cause of Christian unity, and to the imperative of Our Lord’s command that ‘all may be one.’ We include those who have given many years service to the Church in the ordained ministry, and others who are very newly ordained. We believe that we demonstrate the vitality of the tradition which we represent and which has formed us in our discipleship and ministry – a tradition which, we believe, constitutes an essential and invaluable part of the life and character of the Church of England, without which it would be deeply impoverished. -

Dac Members - Biographies

Churchyard DAC MEMBERS - BIOGRAPHIES Membership of the Diocesan Advisory Committee for the Care of Churches 2019 WALKER LAPTHORNE, CHAIR Walker Lapthorne is a Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and a semi – retired Chartered Building Surveyor. He was a Partner of Taylor Lane & Creber, Chartered Surveyors, in Plymouth in the 1980’s and a Director of Stratton Creber until 1996. He joined the established Building Company, J D C Builders in the South Hams and became Managing Director after a management buy out in 2000. The company specialised in high quality new build and refurbishment and specialist conservation works. He has had direct experience of working on major church restoration and reordering projects and has worked on many significant listed buildings throughout South Devon and South East Cornwall. He is the Chair of Trustees for the Eden Cottages Alms Houses in Ivybridge. Walker believes that the development of the Church as the focal point for worship in the community will need to be accommodated by the sensitive adaptation of the buildings to ensure that they remain fit for purpose in modern times. This has to be managed without losing sight of the listed status of many of the churches and the need to ensure that they are conserved for future generations. The reconciliation of this need against the constraints of available budgets will need creative thinking from all Members and Partners of the DAC, to ensure that the appropriate advice is offered. The building stock represents a considerable asset for the Diocese and such assets will need both protection and appreciation of how they can function to serve the mission and ministry as well as the wider community, going forward. -

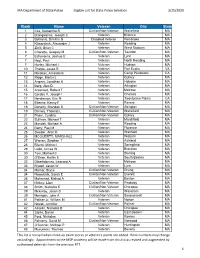

Eligible List for State Police Selection 3/25/2020

MA Department of State Police Eligible List for State Police Selection 3/25/2020 Rank Name Veteran City State 1 Cila, Samantha R Civilian/Non-Veteran Wakefield MA 2 Brangwynne, Joseph C Veteran Billerica MA 3 Bethanis, Dimitris G Disabled Veteran Pembroke MA 4 Klimarchuk, Alexander J Veteran Reading MA 5 Ziniti, Brian C Veteran West Roxbury MA 6 Charette, Gregory M Civilian/Non-Veteran Taunton MA 7 Echevarria, Joshua E Veteran Lynn MA 7 Hoyt, Paul Veteran North Reading MA 7 Hurley, Michael J Veteran Hudson MA 10 Tharpe, Jesse R Veteran Fort Eustis VA 11 Harakas, Amanda K Veteran Camp Pendleton CA 12 Ridge, Martin L Veteran Quincy MA 13 Angers, Jonathan A Veteran Holyoke MA 14 Berg, Alex D Veteran Arlington MA 15 Arsenault, Robert T Veteran Melrose MA 16 Cordes V, Joseph I Veteran Chelsea MA 17 Henderson, Eric N Veteran Twentynine Palms CA 18 Etienne, Kenny F Veteran Revere MA 19 Doherty, Brandon S Civilian/Non-Veteran Abington MA 19 Dorney, Thomas L Civilian/Non-Veteran Wakefield MA 21 Pham, Cynthia Civilian/Non-Veteran Quincy MA 22 Sullivan, Michael T Veteran Marshfield MA 23 Mandell, Michael A Veteran Reading MA 24 Barry, Paul M Veteran Florence MA 25 Sweder, Aron D Veteran Waltham MA 25 MCGUERTY, MARSHALL Veteran Woburn MA 27 Warren, Stephen T Veteran Ashland MA 28 Rivest, Michael Veteran Springfield MA 29 Ladd, James W Veteran Brockton MA 30 Tosi, Michael C Veteran Sterling MA 30 O'Brien, Kaitlin E Veteran South Boston MA 32 Dibartolomeo, Leonard A Veteran Melrose MA 33 Blydell, Jason W Veteran Lynn MA 34 Molnar, Bryce Civilian/Non-Veteran -

Bishop's Award to Recognise Those

FOR OUR GOOD NEWS FROM THE DIOCESE OF EXETER | JUNE 2019 CHURCHES The Dean reflects on WELCOME, NEW the importance of ARCHDEACONS our buildings after the devastating New Archdeacons Notre-Dame fire of Exeter and Plymouth are announced BISHOP’S AWARD TO RECOGNISE THOSE ‘WHO TIRELESSLY GIVE’ he Bishop of Father themselves; displaying moral Exeter has Andrew courage and vision in making Johnson launched an shows the and delivering difficult choices. annual awards St Boniface The Companion of St Boniface medal that investiture to he has medallion has been designed honourT people who have made designed by the Revd Andrew Johnson, a substantial contribution to the assistant curate of Heavitree church in Devon. and Saint Mary Steps, and a The Company of St Boniface professional stained glass artist. will also seek to recognise Father Andrew said: “It took people who have built up between six and nine months overseas links in the Diocese of to achieve the final result. I got Exeter’s witness to Christ. the idea from the St Edward’s Up to six Companions of St Canon’s medal which I designed Boniface will be admitted each a number of years ago. year and a service of investiture “The mitre is at the top of the will be held in Exeter Cathedral People can be nominated to medal because the medal is as close to the feast day of St be recognised with the honour from the bishop and will be from Boniface on June 5 as possible. for a number of reasons Bishop Robert’s successors in The Bishop of Exeter, the including: making a difference time as well.” Right Revd Robert Atwell, said: to the community or in their The deadline for nominations “There are so many members field of ministry; enhancing the this year is September. -

The Voice of Catholic Anglicans Winter 2016

together THE VOICE OF CATHOLIC ANGLICANS WINTER 2016 2017 NATIONAL FESTIVAL Saturday 17th June St John the Baptist, Coventry Fleet Street, Coventry CV1 3AY First things first 12 noon When we think about ‘mission’ – that is, if we think about mission (and I really hope that SOLEMN CONCELEBRATED MASS mission is quickly coming up the PCC agenda of every parish affiliated to The Society) – we’re Principal Celebrant: probably thinking about some kind of plan – even a local ‘mission action plan’. Bishop Roger Jupp, Superior-General Where to start? What to say? What to do? 2.00 pm : Annual Meeting of Associates Who to? Why do it? ‘Have we all got the plan? Synchronize watches …’ 3.00 pm : Exposition, Procession of the Blessed Sacrament and Benediction Priests Associate: those wishing to concelebrate must inform the And then—stupid creatures that Secretary-General via Mary Bashford at: [email protected] we are, only then—we ask God or telephone 0121 382 5533 to bless it, to swing in behind us, to endorse what we’ve put together, to fill our plans with his life and love, and give success to the work of our hands. Put it like that, there’s something clearly not quite right about that approach. It’s dangerously close to thinking that it’s our job to work out how we can take God, even smuggle God, into places and into lives where he’s never been before, when—of course!— God is always, always already in people’s lives, long before we turn up. When we stop and re-think (or when we’ve learnt the hard way because our precious plans have collapsed) we realize that the real mission God gives to us is where he is already opening the door. -

A Thriving Community Message from the Executive Director

SINCE 1980 James, a Plymouth resident a Plymouth James, A THRIVING COMMUNITY MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2016 WAS A CHALLENGING YEAR FOR HOMELESSNESS IN OUR AREA. Tent cities and encampments were, and continue to be, a source of significant public debate. As more people are pushed to the edge of homelessness by rapidly rising rents, the women and men Plymouth serves continue to struggle on the streets, fighting mental illness, chemical dependency, disability, and more. But as we’ve said before: Plymouth is here for the long term. And we’re not alone. As you’ll read about later in this report, we have numerous community partners that support us in this critical work. These partners supplement the services that Plymouth provides; they help our residents succeed in housing by enriching their lives and by building friendships and support networks. I also know that Plymouth needs to do more to meet the desperate need. In 2016, we opened Sylvia Odom’s Place and began construction on Plymouth on First Hill. We also created our next 5-year strategic plan, which was ratified in early 2017. I invite you to read about this plan on page 16, because you’re an integral part of it. Your support—whether monetarily or as a volunteer or advocate—keeps us going. By coming together, we’re rebuilding the lives of men and women experiencing homelessness. And we’ll continue to do so for many years to come. Thank you for being part of our community. Paul Lambros Executive Director 1 MISSION VISION PLYMOUTH HOUSING GROUP’S HOUSING IS JUST THE BEGINNING.. -

Plympton St. Mary

Plympton St. Mary Annual Report and Financial Statements of the Parochial Church Council For the Year ended 31 st December 2007 Incumbent The Rev. M Cameron St Mary’s Vicarage, 209 Ridgeway, Plympton, Plymouth PL7 4HP Bank NatW est, 74/76 Ridgeway, Plympton, Plymouth, PL7 2AF Independent Examiner Mrs P Lillicrap, 7 Campion Way, W oolwell, Plymouth PL6 7TA PLYMPTON. ST. MARY. - ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2008 St. Mary's PCC has the responsibility of cooperating with the incumbent, The Rev. Prebendary Margaret Cameron, to promote in the ecclesiastical parish of Plympton St. Mary the whole mission of the Church, worship, mission and service. We seek to work together pursuing our mission statement: “Serving Christ in the heart of Plympton and beyond.” The Parochial Church Council Members of the PCC are either ex -officio or elected annually at the Annual Parochial Church Meeting (APCM) in accordance with the Church Representation Rules. During the year the following served as members of the PCC: Clergy: (ex officio on PCC) Rev. Prebendary Margaret Cameron, Rev. Roger Beck, Rev. Mark Brimicombe and Rev Harvey Barnes. Wardens: (ex officio on PCC) Mr. Peter Leigh (until May 2007); Mr. Julian Otto and Mr. Keith Escott (from May 2007) Elected to the Deanery Synod, for session ending 2009 (Ex officio on PCC) Mrs. Margaret Leigh, Dr. Tim Smyth Elected Members Elected to 2010 Elected to 2009 Elected to 2008 David Farley Miss Mavis Buttle Mrs. Glenys Otto Alison Thompson Mr. Thomas Allen Mr. David Nicholls Carolyn Wade (resigned) Mr. Keith Shepperd (Treasurer) Miss Lucy Skinner Miss Deborah Tozer (Secretary) Mrs. -

Bishop's Guidelines for Ordained Ministry

VERSION 1.3 JUNE 25, 2020 BISHOP’S GUIDELINES FOR ORDAINED MINISTRY BISHOP’S GUIDELINES FOR ORDAINED MINISTRY CONTENTS Chapter Page Introduction 2 1 Vision and strategy 5 2 Good practice in pastoral ministry 7 3 Safeguarding 12 4 Worship 17 5 Baptism and Confirmation 24 6 Marriage and Civil Partnerships 27 7 Healing and Deliverance Ministry 33 8 Funerals 35 9 Fees 39 10 Sources of support 42 11 Buildings, governance and miscellaneous 56 Appendix: Bishop’s Staff portfolios 63 Diocese of Exeter: Bishop’s guidelines for Ordained Ministry Version 1.3, June 2020 1 Introduction Dear Colleagues, As an inveterate gardener, I value the advice and tips of gardeners more experienced than me. Over the years I have learned that some plants need protecting from frost, others benefit from judicious pruning, and certain plants need the support of a sturdy framework if they are to flourish. These guidelines represent something similar in the realm of ministry. They distil good practice and set out a supportive framework for ministry to help us understand better the obligations and responsibilities we each have as office holders. The guidelines are addressed principally to clergy, but I hope they will be useful to Readers and Licensed Lay Workers as well. All ministry involves a call to holiness of life. Nothing in these pages supersedes the charge laid upon us at our ordinations as set out in the Ordinal. Instead the information here focuses on a range of practical issues. Its guidance should be read in conjunction with the Diocese of Exeter Clergy Terms and Conditions of Service, which sets out the arrangements for those holding office under Common Tenure, and with the national Guidelines for the Professional Conduct of the Clergy as ratified by the Convocations of Canterbury and York on the Church of England website. -

Preparing to Re-Open Our Church Buildings

PREPARING TO RE-OPEN OUR CHURCH BUILDINGS Information from the four Archdeacons for Clergy, Licensed Lay Ministers, Lay Chairs, Churchwardens and PCCs issued on 22nd May 2020 Phases of re-opening Re-opening a church or not? Practicalities Occasional offices THE PHASES OF RE-OPENING It is likely that permission will be given by the government and the national Church for our church buildings to re-open in a phased way over the next couple of months. We have drawn up this document to help clergy and PCCs think through the decisions and actions they need to take in preparation for this. In a Mission Community with more than one church building, we recommend that decisions about which churches will reopen and for what purposes are taken by the Mission Community as a whole. This document covers the following: The likely phases of re-opening churches Whether to re-open a church or not The practical things to consider in relation to Pray: reopening our churches for prayer and worship Grow: how to deepen our church life Serve: how best to serve our local community THANK YOU to all our Occasional offices clergy and laity who are Bellringing working so hard and so Ministers over 70 creatively in the current crisis. The phases of re-opening We cannot know for certain, but we anticipate the phases will be as follows: Phase What is likely to happen Approx. Date Phase 1 Clergy allowed back into their local church for private prayer and Current (as livestreaming of services, including Communion with one member of from 7th May their household.