An Exploration of Prehistoric Ontologies in the Bering Strait Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological and Cultural Evidence for Social Maturation at Point Hope, Alaska: Integrating Data from Archaeological Mortuary Practices and Human Skeletal Biology

BIOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL EVIDENCE FOR SOCIAL MATURATION AT POINT HOPE, ALASKA: INTEGRATING DATA FROM ARCHAEOLOGICAL MORTUARY PRACTICES AND HUMAN SKELETAL BIOLOGY by Lauryn Justice A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Biological and cultural evidence for social maturation at Point Hope, Alaska: Integrating data from archaeological mortuary practices and human skeletal biology A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Lauryn Justice Bachelor of Arts University of North Carolina – Wilmington, 2014 Director: Daniel Temple Department of Anthropology for Master’s Thesis Spring Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA ii Copyright 2017 Lauryn Justice All Rights Reserved iii DEDICATION For my grandparents, David and Claudia Clay, whose unwavering love and constant support makes me believe I can achieve anything. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My deepest thanks are owed to my advisor, Dr. Daniel Temple, for introducing me to the field of bioarchaeology in 2013. I am honored to have had the privilege to work with him during my undergraduate and graduate careers. He is the most brilliant man I have ever known and the knowledge he imparted me has allowed me to grow and become the scholar I am today. My committee members, Dr. Haagen Klaus and Dr. Nawa Sugiyama, also deserve acknowledgement and thanks. -

Evolutionary Psychology, Cognitive Archaeology, and Psychological Prehistory Course Description: This Course Is PSY 325, Evoluti

Evolutionary Psychology, Cognitive Archaeology, and Psychological Prehistory Course Description: This course is PSY 325, Evolutionary Psychology, as offered in the Spring of 2020 Text: Henley, T., Rossano, M., & Kardas, E. (2020). Handbook of Cognitive Archaeology: Psychology in Prehistory. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Note – I know this book is expensive, so there will be a copy placed on reserve in the library that you can use The Basics: Keep in mind that a syllabus sometimes shifts a little as a course unfolds. I say that by way of noting the importance of class attendance, as you will be held responsible for any change in plans announced in class. The other basic admonition every syllabus must include is that cheating (broadly defined) is not allowed. Or, as the university likes me to say: "All students enrolled at the University shall follow the tenets of common decency and acceptable behavior conducive to a positive learning environment (see Student's Guide Handbook, Policies and Procedures, Conduct).” And, note that “Students requesting accommodations for disabilities must go through the Academic Support Committee. For more information, please contact the Director of Disability Resources & Services, Gee Library, Room 132, (903) 886-5835.” Last: Only qualified law enforcement officers or those who are otherwise authorized to carry a concealed handgun in the State of Texas are permitted to do so. Pursuant to Penal Code (PC) 46.035 and A&M-Commerce Rule 34.06.02.R1, even license holders may not carry a concealed handgun in restricted locations. Readings: The readings are listed on the Schedule of Events as follows: key required; required; suggested; and optional. -

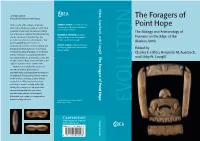

The Foragers of Point Hope Point of Foragers the the Ipiutak and Tigara Archaeological Sites, the and Libby W

Hilton, Auerbach, and Cowgill K SBEA Cambridge Studies in C Y The Foragers of Biological and Evolutionary Anthropology M C At the very tip of the Lisburne Peninsula, CHARLES E. HILTON is an assistant professor in Point Hope Point Hope, Alaska represents one of the best the Department of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. examples of northernmost cultures. Yielding The Biology and Archaeology of one of the largest samples of northern latitude BENJAMIN M. AUERBACH is an assistant skeletal remains in the world it has also professor in the Department of Anthropology at Humans on the Edge of the provided crucial evidence for understanding The University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Alaskan Arctic past foraging lifeways in this remote environment; as well as human, cultural, and LIBBY W. COWGILL is an assistant professor in the Anthropology Department at the University of biological variation in general. Presenting a Edited by Missouri, Columbia. set of anthropological analyses on the human Charles E. Hilton, Benjamin M. Auerbach, skeletal remains and cultural material from The Foragers of Point Hope the Ipiutak and Tigara archaeological sites, The and Libby W. Cowgill Foragers of Point Hope sheds new light on the original excavations from 1939 to 1941. Modern archaeological theory, dental microwear analysis, biomechanics, paleopathology, and population modeling are all employed, bringing these human remains to the forefront of biological anthropology research and addressing debates about subsistence, warfare, activity, and health. Finally, these analyses are integrated into current anthropological perspectives to address the cultural, archaeological, behavioral, and ecological components of human foraging systems. Cover illustration (front): [copy to follow]; EVOLUTION (back): [copy to follow]. -

History, Language, and Culture by the National Park Service

NORTH SLOPE BOROUGH COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2019 — 2039 Part I: North Slope Borough Culture and Planning PAGE 1 NORTH SLOPE BOROUGH PART I | CHAPTER 1: HISTORY, LANGUAGE & CULTURE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2019 — 2039 PAGE 2 NORTH SLOPE BOROUGH PART I | CHAPTER 1: HISTORY, LANGUAGE & CULTURE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2019 — 2039 History, Culture, and Government PAGE 3 NORTH SLOPE BOROUGH PART I | CHAPTER 1: HISTORY, LANGUAGE & CULTURE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2019 — 2039 This page is intentionally left blank PAGE 4 NORTH SLOPE BOROUGH PART I | CHAPTER 1: HISTORY, LANGUAGE & CULTURE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2019 — 2039 Chapter 1. History, Culture, and Government documented human habitation of North NORTH SLOPE HISTORY America. Scientists theorize that the Mesa Site The Iñupiat of the North Slope have a rich was a lookout point for hunters who may have cultural history that is evident in both the living been in search of game that is now extinct, such traditions and numerous archaeological sites on as bison or even mammoth. Since there is no the North Slope. Some villages on the North evidence of later cultures using the site, Slope have been occupied continuously for archaeologists have named this culture the Mesa thousands of years, such as Point Hope, while Culture. The style of weapons found suggest the others were more recently founded as year- Mesa Site was used by a Paleo-Indian culture, of round village sites, such as Atqasuk. However, which no convincing evidence has been found all of the land on the North Slope is rich with elsewhere in Alaska prior to this discovery. Much history and culture evidenced by abundant remains to be learned about this discovery and archeological sites across the entirety of the about the people who hunted in this area borough’s frozen tundra. -

Epistemological Problems in Cognitive Archaeology: an Anti-Relativistic Proposal Towards Methodological Uniformity

doi 10.4436/JASS.91003 JASs Invited Reviews e-pub ahead of print Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 92 (2014), pp. 7-41 Epistemological problems in Cognitive Archaeology: an anti-relativistic proposal towards methodological uniformity Duilio Garofoli1 & Miriam Noël Haidle1,2 1) Zentrum für Naturwissenschaftliche Archäologie, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Rümelinstr. 23, 72070 Tübingen, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2) Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Research Group “The Role of Culture in Early Expansions of Humans,” Research Institute Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, D-60325 Frankfurt/ Main, Germany Summary - Cognitive archaeology (CA) has an inherent and major problem. The coupling between extinct minds, brains and behaviors cannot be investigated in a laboratory. Without direct testability, there is a risk that theories in CA will remain merely subjective opinions in which “anything goes”. To counter this risk, opponents of relativism originally argued that CA should adopt a method of validation based on “indirectly” testing inferences from the archaeological record. In this paper, we will offer a two-part analysis. In the first part, we will discuss problems with the original anti-relativistic agenda. While we agree with the necessity of developing a rational methodology for this discipline, in our view previous analyses have significant weak points that need to be strengthened. In particular, we will propose that “indirect testability” should be superseded by a methodology based upon deductive mappings from networks of theories, followed by a plausibility-selection stage. This methodology will be implemented by adopting an extension of Barnard´s (2010b) proposals for mapping hierarchical systems. In the second part, we will compare our methods with those currently adopted in the CA debate. -

Cognitive Archaeology

Introduction to Archaeology: Class 16 Cognitive archaeology Copyright Bruce Owen 2009 − Cognitive archaeology : What people thought in the past, when they thought it, how they came to think it, and how that affected other things − Two broad foci: − Origins and development of modern human thinking abilities − When did people start thinking like we do, why, how, etc. − Content and influence of thought, as opposed to environment, economics, etc. − What religious ideas have people had, why, and how did that affect their lives and developments in their societies? − How did people understand and explain their world, both the physical world and the social (economic, political, etc.) world? − that is, what have people's ideologies been? − In part, this is a reaction to the excesses of the New Archaeology and the processual approach, which tended to emphasize − adaptation to the environment − economic or material determinism − a systemic view of society in which subsystems or subgroups acted in certain ways in response to certain conditions − reacting to this solely materialist focus, the cognitive archaeology approach emphasizes individuals and what they think as being of interest and having a causal role − in order to understand what people were doing in the past, cognitive archaeologists say you have to understand what they were thinking − their cognitive abilities (in the case of very early humans who may or may not have been fully modern in their psychology) − their ideology and cosmological framework for the world − which shapes their understanding -

Working Together to Preserve the Past

CUOURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT information for Parks, Federal Agencies, Trtoian Tribes, States, Local Governments, and %he Privale Sector <yt CRM TotLUME 18 NO. 7 1995 Working Together to Preserve the Past U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service Cultural Resources PUBLISHED BY THE VOLUME 18 NO. 7 1995 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Contents ISSN 1068-4999 To promote and maintain high standards for preserving and managing cultural resources Working Together DIRECTOR to Preserve the Past Roger G. Kennedy ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Katherine H. Stevenson The Historic Contact in the Northeast EDITOR National Historic Landmark Theme Study Ronald M. Greenberg An Overview 3 PRODUCTION MANAGER Robert S. Grumet Karlota M. Koester A National Perspective 4 GUEST EDITOR Carol D. Shull Robert S. Grumet ADVISORS The Most Important Things We Can Do 5 David Andrews Lloyd N. Chapman Editor, NPS Joan Bacharach Museum Registrar, NPS The NHL Archeological Initiative 7 Randall J. Biallas Veletta Canouts Historical Architect, NPS John A. Bums Architect, NPS Harry A. Butowsky Shantok: A Tale of Two Sites 8 Historian, NPS Melissa Jayne Fawcett Pratt Cassity Executive Director, National Alliance of Preservation Commissions Pemaquid National Historic Landmark 11 Muriel Crespi Cultural Anthropologist, NPS Robert L. Bradley Craig W. Davis Archeologist, NPS Mark R. Edwards The Fort Orange and Schuyler Flatts NHL 15 Director, Historic Preservation Division, Paul R. Huey State Historic Preservation Officer, Georgia Bruce W Fry Chief of Research Publications National Historic Sites, Parks Canada The Rescue of Fort Massapeag 20 John Hnedak Ralph S. Solecki Architectural Historian, NPS Roger E. Kelly Archeologist, NPS Historic Contact at Camden NHL 25 Antoinette J. -

Toward a Phenomenological Cognitive Archaeology

PHILIP TONNER The University of Glasgow [email protected] TOWARD A PHENOMENOLOGICAL COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY abstract Archaeologists, neuroscientists and philosophers all aim to shed light on the holistic and co- constitutive role played by bodies and brains, objects and culture over the course of hominin cognitive evolution. Recent advances in neuroscience and brain imaging have enabled exploration of the foundation for tool using capacity in modern human brains. In tandem with this has been the development of cognitive archaeology, a perspective that seeks to uncover and engage with past ways of thought, as these can be inferred from surviving material remains. What I will suggest in this paper is that the phenomenological perspective can contribute to the methodological drive in cognitive archaeology. Phenomenology provides just the kind of access to consciousness and the mind required for an understanding of “ways of thought and action”, including past ways of thought and action, to emerge. I will argue that pragmatic meaning- bestowing agency is operative throughout the Palaeolithic and I will suggest how empirical evidence can be understood in the terms suggested by phenomenological philosophers. keywords Phenomenology; cognitive; archaeology; tools; manufacture; agency TOWARD A PHENOMENOLOGICAL COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY PHILIP TONNER The University of Glasgow 1. Archaeologists, neuroscientists and philosophers all aim to shed light on the holistic and co-constitutive role played by bodies, brains, objects and worlds throughout hominin cognitive evolution. Hominins include modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) and all of our fossil ancestors: hominins are hominids, as are the great apes (Coward and Gamble 2009, p. 64). Archaeology can, with an increasing precision, tell us where and when modern humans emerged: Africa between 100.000 and 200.000 years ago. -

Birds, Needles, and Iron: Late Holocene Prehistoric Alaskan

birds, needles, and iron: late holocene prehistoric alaskan grooving techniques Carol Gelvin-Reymiller Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, PO Box 757720, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7720; [email protected] Joshua Reuther University of Arizona and Northern Land Use Research, Inc., PO Box 83990, Fairbanks, AK 99708 [email protected] abstract This article considers questions in prehistoric technology by examining organic artifacts from sev- eral Alaska Late Holocene sites, including Croxton Site Locality J at Tukuto Lake, western Brooks Range. Examples of bone needle “cores” and needles crafted from large bird humeri are measured and microscopically examined to distinguish possible differences in tools and reduction techniques. Tool handles used to accomplish grooving, including “engraving tool handles,” as well as differences between iron and stone bits, are discussed. Archaeometric data, avian ecology, and ethnographic ac- counts are explored to investigate aspects of needle manufacture, the introduction of iron, and the potential relationships people had to these materials and objects. keywords: Avifauna, needles, bone, technology, Ipiutak, engraving introduction Grooving technologies, the processes by which organic In addition to the analysis of bird bone cores and the materials were divided and shaped, were frequently put to nature of bird bone itself, we consider the construction use by arctic and subarctic cultures. These processes have of tools required to accomplish grooving, including “en- been studied by archaeologists to some degree and con- graving tool handles” (sic Larsen and Rainey 1948) and tinue to be of interest for understanding tool manufac- other handles, as well as bits associated with grooving ture. Semenov’s well-known Prehistoric Technology (1976 techniques. -

Le Plant and Driftwood Use at Cape Espenberg, Alaska

Thule Plant And Driftwood Use At Cape Espenberg, Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors Crawford, Laura J. Download date 28/09/2021 20:16:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8578 THULE PLANT AND DRIFTWOOD USE AT CAPE ESPENBERG, ALASKA By Laura J. Crawford RECOMMENDED: £,L Advisory Committee Chair Advisory Committee Chair Chair, Department of Anthropology APPROVED: Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts A: Dean of the Graduate School THULE PLANT AND DRIFTWOOD USE AT CAPE ESPENBERG, ALASKA A THESIS Presented to the Faculty Of the University of Alaska Fairbanks In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Laura J. Crawford, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska August 2012 © 2012 Laura J. Crawford UMI Number: 1521779 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 1521779 Published by ProQuest LLC 2012. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis addresses the question of Thule plant and woody fuel use at Cape Espenberg, Alaska between approximately AD 1500 and 1700. The objective of this thesis is to determine how the Thule at Cape Espenberg were using various plant species, including edible plant species and fiielwood species. -

Archaeology: the Key Concepts Is the Ideal Reference Guide for Students, Teachers and Anyone with an Interest in Archaeology

ARCHAEOLOGY: THE KEY CONCEPTS This invaluable resource provides an up-to-date and comprehensive survey of key ideas in archaeology and their impact on archaeological thinking and method. Featuring over fifty detailed entries by international experts, the book offers definitions of key terms, explaining their origin and development. Entries also feature guides to further reading and extensive cross-referencing. Subjects covered include: ● Thinking about landscape ● Cultural evolution ● Social archaeology ● Gender archaeology ● Experimental archaeology ● Archaeology of cult and religion ● Concepts of time ● The Antiquity of Man ● Feminist archaeology ● Multiregional evolution Archaeology: The Key Concepts is the ideal reference guide for students, teachers and anyone with an interest in archaeology. Colin Renfrew is Emeritus Disney Professor of Archaeology and Fellow of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge. Paul Bahn is a freelance writer, translator and broadcaster on archaeology. YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN THE FOLLOWING ROUTLEDGE STUDENT REFERENCE TITLES: Archaeology: The Basics Clive Gamble Ancient History: Key Themes and Approaches Neville Morley Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in the Greek World John Hazel Who’s Who in the Roman World John Hazel ARCHAEOLOGY The Key Concepts Edited by Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX 14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY: in SEARCH of the EARLIEST SYNTACTIC LANGUAGE-USERS in HIMALAYA Maheshwar P

COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY: IN SEARCH OF THE EARLIEST SYNTACTIC LANGUAGE-USERS IN HIMALAYA Maheshwar P. Joshi Recent scientific studies unfold that neural structures bearing on intonation of speech have a deep evolutionary history traced to mammal-like reptiles called therapsids found in the Triassic period (∼252.17 mya, million years ago). Therefore, these structures were already present in the primates. It goes to the credit of Homo sapiens who developed it to the extent that humans are defined as symbolling animals, for language is the most articulated symbolism. Cognitive archaeology makes it clear that it took hominins millions of years to develop a syntactic language. Stratigraphically controlled and securely established artefact-bearing sites of the Middle Palaeolithic Arjun complex in the Deokhuri Valley, West Nepal, provide firm dates for the presence of the earliest syntactic language speakers in Himalaya from 100 ka to 70 ka (thousand years ago). Keywords: cognitive archaeology, neural structure, syntactic language, verbal communication, Arjun complex 1. Introduction Study of prehistory of language falls in the domain of cognitive archaeology and this discipline ‘is still in early development’ (Renfrew 2008: 67). To the best of my information, no scholar studying South Asian prehistory has addressed this issue despite the fact that South Asia is very rich in material culture vis-à-vis prehistory of language (see for details, Joshi 2014: in press-a; Joshi 2017: in press-b). Since my primary concern in this essay is Himalaya in general and Central Himalaya in particular, I will focus on the earliest syntactic language-users in the context of Central Himalaya.