687 UNION: OCSEA, Local 11, AFSCME, AFL-CIO EMPLOYER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile X-Ray Unit Slated in Cass City All Day Tuesday Deford Methodists

SECTION ONE SECTION ONE PAGES 1 TO 8 PAGES 1 TO 8 Sixteen Pages C ASS CITY CHRONICLE Sixteen Pages VOLUME 48, NUMBER 3. CASS CITY, MICHIGAN PEIDAY, MAY 15, 1953. Sixteen Pages Hold Prayer Service Deford Methodists to Hold Edward Gingrich For Gerald Hartwick Annual Value Days Expected E Dedication Service Sunday Killed in Car-Bus To Attract Thumb Shoppers You might expect a person to Dr.. E. Bay Willson, district > Sponsored by the Cass City fail to put on his license plates superintendent for the Methodist Chamber of Commerce, the third shortly after the time had expired Church, will be in Deford Sunday Mrs. Carpenter to Collision Tuesday Former Cass Cityite annual Cass City Value Days, in March, but not to have them on to take charge of the dedication Lead Discussion at which starts today, is expected to in May is unusual. service scheduled at the Deford Speaks at Rotary draw record crowds to Cass City But Dale Kettlewell, who takes Methodist Church. Cass City Friday Edward Gingrich, 73, of Bay to take advantage of the many frequent trips throughout the state Members of the church have City, was killed Tuesday when his Capt. William H, Spencer, chief bargains in nearly every local for furniture, has to learn the completed an ambitious expansion car skidded into a school bus while pilot of the international division store. The village-wide sale dates hard way. The other day on one of program that includes a new full- "One World" is a panel discus- he was trying to stop in obedience of the Philippine Air Line, told are today "and Saturday. -

Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

MERCY HIGH SCHOOL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED TWICE YEARLY FOR ALUMNAE, PARENTS & FRIENDS FALL / WINTER 2020 Mya Williams '21 Susan Smith '84 Mary Harkness '70 Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Principal Patricia Sattler Julia Bishop '21 DEI Angela Rea '20 INSIDE THIS 2019-20 Honor Roll of Donors • Mercy Moments & Awards mhsmi.org I SSUE Staff Salute • Alumnae Class Notes CREATED BY MERCY’S FOUNDING MOTHER OF ART MARY IGNATIUS DENAY, RSM A MOSAIC IS AN ARRAY OF DIVERSE ELEMENTS JOINED TOGETHER TO CREATE A GREATER WHOLE. Mercy High School Board of Trustees Jared P. Buckley - Chair MHSMI.ORG Cheryl Delaney Kreger, Ed.D. ’66 - President Visit Diana Mercer-Pryor - Treasurer Stay connected with what's happening at Dave Hall - Secretary Mercy. Read and sign up to receive alumnae Nancy Auffenberg and parent e-newsletters, browse Anne Blake, Ph.D. Mercy High School the school year calendar, and check out Robert Casalou 29300 W. 11 Mile Road Mercy activities and news. Margaret Dimond, Ph.D. ’76 Susan Hartmus Hiser Farmington Hills, MI 48336-1409 Brigid Johnson, RSM Email: [email protected] Karla Rose Middlebrooks ’76 Tel: (248) 476-8020 Carla LaFave O’Malley ’70 Fax: (248) 476-3691 Marisa C. Petrella ’77 Mercy Sharon Sanderson Anita Sevier Paul E. Swanson MOSAIC Rita Marie Valade, RSM ’72 ERCY IGH CHOOL High School M H S Board Support Staff MAGAZINE Patricia Sattler - Principal MISSION STATEMENT Colleen McMaster ’81 Editors - Associate Principal Academic Affairs Julie Earle, Maria Siciliano Mueller - Director of Finance Mercy High School, Director of Communications -

CITY COUNCIL Meeting Agenda

CITY COUNCIL Meeting Agenda REGULAR MEETING MONDAY, JANUARY 8, 2018 COUNCIL CHAMBERS 7:00 P.M. The Regular Meetings of City Council are filmed and can be viewed LIVE while the meeting is taking place or at your convenience at any time after the meeting on the City’s website at www.ReadingPa.gov, under “Live and Archived Meeting Videos”. All electronic recording devices must be located behind the podium area in Council Chambers and located at the entry door in all other meeting rooms and offices, as per Bill No. 27-2012. RULES FOR PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AT COUNCIL MEETINGS The Administrative Code, Section § 5-209 defines public participation at Council meetings. 1. Citizens attending Council meetings are expected to conduct themselves in a responsible and respectful manner that does not disrupt the meeting. 2. Those wishing to have conversations should do so in the hall outside Council Chambers in a low speaking voice. 3. Public comment will occur only during the Public Comment period listed on the agenda at the podium and must be directed to Council as a body and not to any individual Council member or public or elected official in attendance. Clapping, calling out, and/or cheering when a speaker finishes his comments is not permitted. 4. Citizens may not approach the Council tables at any time during the meeting. 5. Any person making threats of any type, personally offensive or impertinent remarks or any person becoming unruly while addressing Council may be called to order by the Presiding Officer and may be barred from speaking, removed from Council Chambers and/or cited. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ______

RECOMMENDED FOR FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 206 File Name: 06a0474p.06 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT _________________ LARRY M. YOUNG, X Plaintiff-Appellant, - - - No. 05-2633 v. - > , TOWNSHIP OF GREEN OAK, - Defendant-Appellee. - - - N Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan at Detroit. No. 02-71891—Denise Page Hood, District Judge. Argued: October 30, 2006 Decided and Filed: December 28, 2006 Before: SILER, GILMAN, and GRIFFIN, Circuit Judges. _________________ COUNSEL ARGUED: Peter J. Osetek, OSETEK & ASSOCIATES, Ann Arbor, Michigan, for Appellant. Gregory A. Roberts, Joseph Nimako, CUMMINGS, MCCLOREY, DAVIS & ACHO, Livonia, Michigan, for Appellee. ON BRIEF: Peter J. Osetek, OSETEK & ASSOCIATES, Ann Arbor, Michigan, for Appellant. Gregory A. Roberts, Joseph Nimako, CUMMINGS, MCCLOREY, DAVIS & ACHO, Livonia, Michigan, for Appellee. _________________ OPINION _________________ RONALD LEE GILMAN, Circuit Judge. Larry M. Young appeals from the grant of summary judgment in favor of his former employer, the Township of Green Oak, Michigan. He claims that he was wrongfully discharged from his position as a police officer for the Township. For the reasons set forth below, we AFFIRM the judgment of the district court. 1 No. 05-2633 Young v. Green Oak Township Page 2 I. BACKGROUND A. Factual background Larry M. Young, a veteran of the United States Navy, began working as a police officer for the Green Oak Township Police Department in 1978. In August of 1992, Young suffered a back injury during a training exercise. The injury was diagnosed as a herniated disc, which prevented Young from working for several days. -

INDIANA HEALTH LAW REVIEW Volume 13 2015-2016

INDIANA HEALTH LAW REVIEW Volume 13 2015-2016 Editor-in-Chief Patricia Connelly Executive Managing Editor Executive Notes Editor Ladene Mendoza Maggie Little Executive Editor Executive Articles Editor Jonathon Welling Samantha Weichert Executive Business Editor Executive Production Editor Latoya Highsaw Spenser Benge Executive Symposium Editor Grace Shelton Note Development Editors Articles Editors Matt Elliot Jordan Brougher Bailey Box Brad Lohmeier Scott Knight Michael Knight Scott Watanabe Note Candidates Aileen Worden Kelci Dye Andrew C. Hanna Lee Stoy Ben Brown Nick Erickson Caroline Emhardt Nicholas Golding Chelsea Crawford Portia Bailey Diego Wu Min Ryan Garner Janet Horne Shamika Mazyck Jesse Wyatt Tyler J. Holmes Joey Keller Tyler S. Lemen Kayla Ellis Victoria Howard Faculty Advisors Nicolas P. Terry (Chair) David Orentlicher (Chair) Eleanor D. Kinney (Adviser Emerita) Robert A. Katz Emily Morris Miriam Murphy (Research Liaison) Ben Keele (Research Liaison) INDIANA HEALTH LAW REVIEW Content. The Indiana Health Law Review publishes articles submitted by academics, practitioners, and students on the topics of health law and policy. The scope includes bioethics, malpractice liability, managed care, anti-trust, health care organizations, medical-legal research, legal medicine, and food and drug law. The Indiana Health Law Review will be published twice during the 2015-2016 academic year. Disclaimer. The ideas, views, opinions, and conclusions expressed in articles appearing in this publication are those of the authors and not those of the Indiana Health Law Review or Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. Subscriptions. Claims for non-receipt of the current year’s issues must be made within six months of the mailing date. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Touch and Go…Magazine (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Sex Master…Squeeze (7/78) Surrender…Cheap Trick (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) I Wanna Be Sedated (megamix)…The Ramones (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) I See Red…Split Enz (12/78) Roxanne…The -

The Plain Meaning of Oncale

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 7 (1998-1999) Issue 3 Symposium: Strengthening Title VII: Article 8 1997-1998, Sexual Harassment Jurisprudence April 1999 The Plain Meaning of Oncale Catherine J. Lanctot Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Repository Citation Catherine J. Lanctot, The Plain Meaning of Oncale, 7 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 913 (1999), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol7/iss3/8 Copyright c 1999 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE PLAIN MEANING OF ONCALE Catherine J. Lanctot* The unanimous Supreme Court opinion in Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc. caught many observers by surprise. Even more surprisingthan the Court's unanimity on the divisive issue of same-sex harassment,however, was the author of the opinion-the deeply conservative Justice Antonin Scalia. Many commentators suggest that the opinion's requirement that plaintiffs prove that the harassmentwas "because of sex" will hamper lawsuits arisingfrom single-sex work environments. Attempts tofit the decision within traditionalTitle VIIjurisprudence inevitablywill be clouded by conjecture about Scalia's true intent. Indeed, after one year of experience with Oncale, the judicialrecord is decidedly mixed The debate over Oncale's meaning has manifested itself most clearly in an emerging dispute over the role of summaryjudgment in resolving harassmentcases. Nevertheless, in attempting to apply a new Supreme Court opinion,particularly one joined by all nine Justices, it is the holding of the opinion that must guide the lower courts, not the assortedexamples, exhortations,and suggestions that accompany it. -

שנה טובה Shana Tova Booklet with Yizkor Remembrance Pages 2020/5781

שנה טובה Shana Tova Booklet with Yizkor Remembrance Pages 2020/5781 14005A N. Dale Mabry Hwy | Tampa, FL 33618 813-963-1818 | mekorshalom.org Table of Contents Message from Hazzan Sered-Lever President's Message from Yael Hatfield This Month's Holiday Programming Shabbat @ Virtual Mekor Shalom Volunteer for a Team Adult Lifelong Learning (ALL) Religious School | Bar/Bat Mitzvah Save the Date Yizkor Remembrances Frequent Chai-er Program Joining Mekor Shalom Board of Trustees High Holiday Service Schedule Todah rabbah (Thank you) to: Arlene Abrams-Bernstein, Steve "Captain Mahzor" Bernstein, Yael Hatfield, and Ellen Kaslow (Shulman) for taking care of the mahzor distribution. Dr. Jen Goldberg for sharing her skills as a master educator in leading the Round Challah Days Children's Services. Henry Hatfield for scanning the entire mahzor to make it available for download. Nevin Hatfield for graciously sounding the shofar again this year. It's always a moving experience. Each and every one of you for being here and for believing in your synagogue. Message from Hazzan Sered-Lever Dear Friends, Last year in this space I suggested that "the new year beckons us to try something new or different." Well, in so many ways, we certainly have been living in the Land of Different. One piece that is very different is that this year's services are virtual. This change of not having High Holiday services in person may feel destabilizing and/or uncomfortable. To help us find our footing, let's think about what about this experience may still feel familiar and help to ground us. -

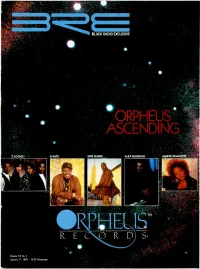

•Sorphe •'ASCEND

• • • z • I. •,. BLACK RADIO EXCWSIVE e • • 46. • • sORPHE , • 'ASCEND • VLOOKE B-FATS ERIC GABLE ALEX BUGNON ALEESE SIMMONS TM R E e • Volume XIV No. 2 January 27, 1989 $5.00 Newspaper fie IC9 SPECIAL EVERTS AND ARTISTS YOU W ON'T WANT TO MISS!!! Opening Cocktail ReceptIon Dance Party Hosted by MCA Records Scholarship Foundation Donner Late Night Party At Tipitinas Store Manager s Party at Tower Records Special Program for Spouses. Companions & Guests BUSINESS SESSIONS SEMINARS • EXHIBITAREA NURCHANDISER OF THE YEAR AWARDS BEST SELLER AWARDS PRODUCT PRESENTATIONS BY: • IsmG DISTRIBUTION/RCA RECORDS/ • INDEPENDENT MANUFACTURERS a, DISTRIBUTORS A&M REC ORDS/ARISTA RECORDS • MCA DISTRIBUTING CORP Wayne loups iSt Zydecajun •CEMA DISTRIBUTION • POLYGRAM RECORDS • WARNER/ELEKTRA/ATLANTIC CORP • CIS RECORDS, INC PowGram Records et COLUMBIA/EPIC -PORTRAIT- ASSOCIATED LAIRS VitGfCIS MAStERW ORIES/CHRYSAUS REC ORDS wei*-tet ttie NAkrtt 6»we'rction, Name Registration Fee $595 O T D Retailer Spouse Fee $225 Company ID Record Manufacturer Of roo m is requested $120 n Wholesaler Address__ encloser deposit) fl Other PLEASE SPECIFY Total Enclosed 1 fir S funds only/ Phone ( ) FAX ( ) Room Reservations keynote Arrival Departure "Peakeusr:cyo, Return Coupon to: -oodoi Em , Snl ith National Association of Recording Merchandisers 3 Eves Drive, Sude 307 Marlton, NJ 08053 USA (609) 596-2221 PLUS PLENTY OF rot Ofnc• Use Only CHECK I BATCH E CO MPANY o REGISTRAn ON DATE ETC D TOTAL FUNDS ROO M DEPOSIT NEW ORLEANS MUSICAL PLEASE DUPLICATE THIS FORM FOR ADDITIONAL REGISTRANTS SURPRISES!!! a\TENTS Publisher SIDNEY MILLER Assistant Publisher SUSAN MILLER VP/General Manager JANUARY 27. -

Who's Who in R&B Record Production

WHO'S WHO IN R&B RECORD PRODUCTION The following is a list of PRODUCERS credited with at least one record in the Top 50 R&B Charts from January 1992 to the present TOs Msting JncJudes the PRODUCER'S Name (# of records credited) "Song Title" - Artist/ Other PRODUCERS credited on the record. Hakeom Abdulsamad(l) - "The Saga Continues...'-The Boys-/ Diamond(l) - "Punks Jump Up To Get Back Down"- Brand Nubian-/ Daniel Abraham(1) - "Crazy Love"-Cece Peniston-/ Clifton Dillon(3) - "Mr. Loverman'-Shabba Ranks-/Michael Bennett + "Flex"- Mad Cobra-/ + "Slow And Walter Afanaeieff(5) - "Lost In The Night'-Peabo Bryson-/Barry Mann + 'I'll Be There'-Mariah Carey- Sexy"-Shabba Ranks & Johnny GillVJimmy Jam Terry Lewis Clifton Dillon /Mariah Carey + "Someone To Hold"-Trey LorenzVMariah Carey + "A Whole New World (Aladdin's D-J- Doc(1) - "Poor Georgie"-MC Lyte-/ Theme)"-Peabo Bryson & Regina Belle-/ "Photograph Of Mary"-Trey LorenzVMariah Carey Tony Dofat(1) - "Who's The Man"- Heavy D. & The Boyz-/ Lance Alexander^) - "I Got AThang 4 Ya'- Lo-Key-/Tony Tolbert + "Love Make:; No Sense"-Alexander Don-EM) - "Love Makes The World Go Round"- Don-E-/ O'Neal-/Professor T. + "Sweet On LT- Lo-Key-/Professor T. °°U0 E- Fresh(1) - "Bustin1 Out(On Funk)"- Doug E. Fresh-/One Cause Tim Allen(2) - "When Only A Friend Will Do"-Mike Davis-/ + "She's Playing Hard To Get"- Hi 5V D™" Low Prod'ns.(2) - "I Don't Mind"- Big Bub-/ + Tellin' Me Stories"- Big Bub-/ Rico Anderson(2) - "Oochie Coochie"-M.C. Brains-/ + "1-4-AI1-4-1"- East Coast Family-/ °°}Nn Low Prod'ns.(1) - "I Don't Mind"- Big Bub-/ Aaron Arce(1) - "Helluva"- Brotherhood Creed-/David Michery Dr- Dre(3)' "Deep Cover"- Dr. -

April 21, 2019

WEEKLY BULLETIN April 21, 2019 THIS MORNING’S LESSON: Worship Order Praise Song “Then the Lord God Shepherd’s Welcome / Prayer formed man of dust from Song the ground, and breathed Lord’s Supper Song into his nostrils the breath Offering of life; and man became a Song living being.” Prayer Song Genesis 2:7 (NASB) Scripture Lesson Invitation Song Reminders REGISTRATION REQUEST: Please use the card Dismissal Prayer in the pew in front of you to note your attend- ance (white for members and blue for visitors) PM Service and PLEASE SIGN UP FOR WEDNESDAY NIGHT MEAL. 6:00… Assembly … Auditorium PARENTS OF CHILDREN AGES 3-6: Happy Birthday Children’s Worship is provided during the morn- April 23 … Jean Weaver ing worship. Children will be dismissed before the sermon. April 26 … Jep Wisdom April 27 … Rodney Weath- erspoon WHERE WE ARE Office: 251.344.2366 ucchrist.org facebook.com/ucchrist We are excited that you chose to worship with us today! It is our hope that you experience the love of Christ this NEW WITH US? morning during our worship. • We offer classes for all age groups from newborns to adults. Our greeters would be happy to show you and your family to our classes. ? • A fully staffed nursery is available during worship services. • If you have any questions about what you see and hear this morning, our ushers are happy to help you find the right person with which to discuss these matters INFO CENTER SERVICE TIMES SUNDAY: Bible Class 9:30 a.m., Worship 10:30 a.m.