Modernity, Socialization and Failure in Works of Franz Kafka and Hannah Arendt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1 David Pan In the “Sirens” episode in Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus, relying on nothing more than the wax in his sailors’ ears and the rope binding him to the mast of his ship, was able to hear the sirens’ song without being drawn to his death like all the sailors before him.2 Franz Kafka, finally giving the sirens their due, points out that their song could certainly pierce wax and would lead a man to burst all bonds. Instead of attributing Odysseus’ sur- vival to his cunning use of technical means, which he calls “childish mea- sures,”3 Kafka attributes it to the sirens’ use of an even more horrible weapon than their song: their silence. Believing his trick had worked, Odysseus did not hear their silence, but imagined he heard the sound of their singing, for no one could resist “the feeling of having triumphed over them by one’s own strength, and the consequent exaltation that bears down everything before it.”4 The sirens disappeared from Odysseus’per- ceptions, which were focused entirely on himself. Kafka concludes: “If the sirens had possessed consciousness, they would have been annihilated at that moment. But they remained as they had been; all that had hap- pened was that Odysseus had escaped them.”5 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno have argued that this ancient 1. From Primitive Renaissance: Rethinking German Expressionism by David Pan. Copyright 2001 by the University of Nebraska Press. 2. Homer, Odyssey, Book 12, pp.166-200. 3. -

1 the Threats of Sleep In

Emergence: A Journal of Undergraduate Literary Criticism and Creative Research 1 COPYRIGHT NOTICE. Quotations from this article must be attributed to the author. Unless otherwise indicated, copyright for this article belongs to the author, who has granted Emergence first-appearance, non-exclusive rights of publication. The Threats of Sleep in ''The Metamorphosis'' Rebecca Chenoweth Kafka's writings are often lauded for their treatment of the absurd. In ''The Metamorphosis,'' this absurdity is most visible in Gregor Samsa's transformation into a giant insect, but most tellingly also expresses itself in his attitude toward his transformation. In a text that deals so closely with the inversion of the dream-like and reality, Gregor's relationship to sleep speaks volumes about the nature of his metamorphosis. When engaging the theme of sleep in Kafka's works, literary critics have often examined its ''dream-like'' elements, as well as Kafka's own relationship to sleep. This paper examines a third perspective on this theme: the role of sleep as a physical act, and what it reveals about Gregor's state. Gregor sees sleep at times as the cause of and other times as a possible cure for his metamorphosis. His inability to sleep is a troubling indicator that he is losing his grip on life and humanity after his transformation, but his relationship to sleep before the metamorphosis shows how long he has really been dehumanized. Most literary criticism that treats the theme of sleep in ''The Metamorphosis'' focuses on the ways in which it is ''dream-like.'' As is the case with most of Kafka's writings, Gregor's story is often described in terms of a nightmare, despite its being explicitly presented as ''no dream'' (Kafka 89). -

An Unheard, Inhuman Music: Narrative Voice and the Question of the Animal in Kafka's “Josephine, the Singer Or the Mouse

humanities Article An Unheard, Inhuman Music: Narrative Voice and the Question of the Animal in Kafka’s “Josephine, the Singer or the Mouse Folk” Kári Driscoll Department of Languages, Literature, and Communication, Utrecht University, Utrecht 3512 JK, The Netherlands; [email protected] Academic Editor: Joela Jacobs Received: 28 March 2017; Accepted: 26 April 2017; Published: 3 May 2017 Abstract: In The Animal That Therefore I Am, Derrida wonders whether it would be possible to think of the discourse of the animal in musical terms, and if so, whether one could change the key, or the tone of the music, by inserting a “flat”—a “blue note” in other words. The task would be to render audible “an unheard language or music” that would be “somewhat inhuman” but a language nonetheless. This essay pursues this intriguing proposition by means of a reading Kafka’s “Josephine, the Singer or the Mouse Folk,” paying careful attention to the controversy regarding the status of Josephine’s vocalizations, which, moreover, is mirrored in the scientific discourse surrounding the ultrasonic songs of mice. What is at stake in rendering this inhuman music audible? And furthermore, how might we relate this debate to questions of narrative and above all to the concept of narrative “voice”? I explore these and related questions via a series of theoretical waypoints, including Paul Sheehan, Giorgio Agamben, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, and Jean-Luc Nancy, with a view to establishing some of the critical parameters of an “animal narratology,” and of zoopoetics more generally. Keywords: narrative voice; inoperativity; singing mice; zoopoetics; anthropological machine; community; music Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on —Keats 1. -

Modernist Permabulations Through Time and Space

Journal of the British Academy, 4, 197–219. DOI 10.5871/jba/004.197 Posted 18 October 2016. © The British Academy 2016 Modernist perambulations through time and space: From Enlightened walking to crawling, stalking, modelling and street-walking Lecture in Modern Languages read 19 May 2016 ANNE FUCHS Fellow of the Academy Abstract: Analysing diverse modes of walking across a wide range of texts from the Enlightenment period and beyond, this article explores how the practice of walking was discovered by philosophers, educators and writers as a rich discursive trope that stood for competing notions of the morally good life. The discussion proceeds to then investigate how psychological, philosophical and moral interpretations of bad prac- tices of walking in particular resurface in texts by Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann and the interwar writer Irmgard Keun. It is argued that literary modernism transformed walking from an Enlightenment trope signifying progress into the embodiment of moral and epistemological ambivalence. In this process, walking becomes an expression of the disconcerting experience of modernity. The paper concludes with a discussion of walking as a gendered performance: while the male walkers in the modernist texts under discussion suffer from a bad gait that leads to ruination, the new figure of the flâneuse manages to engage in pleasurable walking by abandoning the Enlightenment legacy of the good gait. Keywords: modes of walking, discursive trope, Enlightenment discourse, modernism, modernity, moral and epistemological ambivalence, gender, flâneuse. Walking on one’s two legs is an essential but ordinary skill that, unlike cycling, skate-boarding, roller-skating or ballroom dancing, does not require special proficiency, aptitude or thought—unless, of course, we are physically impaired. -

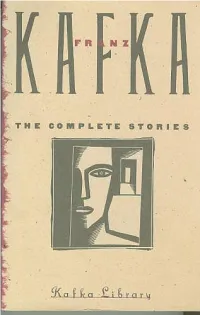

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 73-20,631

THE EFFORT TO ESCAPE FROM TEMPORAL CONSCIOUSNESS AS EXPRESSED IN THE THOUGHT AND WORK OF HERMAN HESSE, HANNAH ARENDT, AND KARL LOEWITH Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Olsen, Gary Raymond, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 18:13:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288040 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Paga(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Introduction

Guston, Philip Guston 9/8/10 6:04 PM Page 1 INTRODUCTION DORE ASHTON “Create, artist! Don’t talk!” the aging Goethe counseled his contemporaries in 1815. The painter Degas seconded the old sage when he told the young poet Paul Valéry that when the muses finished their day’s work they didn’t talk, they danced. But then, as Valéry vividly recalled, Degas went on to talk of his own art for hours on end. Painters have always talked, and some, such as Delacroix, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Malevich, and Motherwell, also wrote. Certain painters, Goya, for example, also deftly used language to augment their imagery. Like Degas, who liked to talk with poets and even engaged the inscrutable Mallarmé, Guston liked talking with poets, and they with him. Among his most attentive listeners was his friend the poet Clark Coolidge, whose ear was well attuned to Guston’s sometimes arcane utterances and who has selected some of the painter’s most eloquent sessions of writing and talking, resulting in a mosaic of a life - time of thought. I was also one of Guston’s interlocutors for almost thirty years. I recognize with pleasure Coolidge’s unfurling of Guston’s cycles of talk and non-talk; his amusing feints and dodges when confronted with obtuse questioners, his wondrous bursts of language when he felt inspired, his sometimes playful contrariness, his satisfaction in being a provocateur, and his consistent preoccupation with serious aesthetic ques - tions through out his working life as a painter. Above all, I recognize Guston’s funda - mental rebelliousness, which manifested itself not only in his artistic preferences but in his politics, his choice of artistic battlefields, and his intimate studio life. -

Metamodernism, Or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism

“We’re Lost Without Connection”: Metamodernism, or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism MA Thesis Faculty of Humanities Media Studies MA Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Giada Camerra S2103540 Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden, 14-06-2020 Supervisor: Dr. M.J.A. Kasten Second reader: Dr.Y. Horsman Master thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations of Leiden University 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Discussing postmodernism ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Postmodernism: theories, receptions and the crisis of representation ......................................... 10 1.2 Postmodernism: introduction to the crisis of representation ....................................................... 12 1.3 Postmodern aesthetics ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.1 Sociocultural and economical premise ................................................................................. 14 1.3.2 Time, space and meaning ..................................................................................................... 15 1.3.3 Pastiche, parody and nostalgia ............................................................................................ -

Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Bäckström, P. (2008) One Earth, Four or Five Words: The Notion of ”Avant-Garde” Problematized Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-89603 ACTION YES http://www.actionyes.org/issue7/backstrom/backstrom-printfriendl... s One Earth, Four or Five Words The Notion of 'Avant-Garde' Problematized by Per Bäckström L’art, expression de la Société, exprime, dans son essor le plus élevé, les tendances sociales les plus avancées; il est précurseur et révélateur. Or, pour savoir si l’art remplit dignement son rôle d’initiateur, si l’artiste est bien à l’avant-garde, il est nécessaire de savoir où va l’Humanité, quelle est la destinée de l’Espèce. [---] à côté de l’hymne au bonheur, le chant douloureux et désespéré. […] Étalez d’un pinceau brutal toutes les laideurs, toutes les tortures qui sont au fond de notre société. [1] Gabriel-Désiré Laverdant, 1845 Metaphors grow old, turn into dead metaphors, and finally become clichés. This succession seems to be inevitable – but on the other hand, poets have the power to return old clichés into words with a precise meaning. Accordingly, academic writers, too, need to carry out a similar operation with notions that are worn out by frequent use in everyday language. -

Kafka and the Postmodern Divide: Hebrew and German in Aharon Appelfeld’S the Age of Wonders (Tor Ha-Pela’Ot)

THE GERMANIC REVlEW Kafka and the Postmodern Divide: Hebrew and German in Aharon Appelfeld’s The Age of Wonders (Tor Ha-pela’ot) DAVID SUCHOFF uch recent cultural criticism has argued that postmodern culture can be di- M agnosed as an unworked-through period of mourning, unable to come to terms with the Holocaust and the definitive break with modernist categories that it represents.’ Aharon Appelfeld’s Hebrew novella The Age of Wonders (1978) portrays the story of an assimilated Jewish writer and his family in Austria be- fore the Holocaust, and the story of his son Bruno, who returns to Austria from Jerusalem after the war in search of his past. The text’s very structure seems to affirm the traditional categories of the modedpostmodern divide. Bruno’s father seems to represent the formalism of modernist fiction and its paradigmatic eth- nic self-denial. As the Holocaust draws near in the first half of the novella, Jew- ish history is truly the nightmare from which the writer, as the “father” of Bruno’s apparently rootless, postmodern fate, unsuccessfully tries to awaken. “Father” (his only consistent name in the novella) constantly seeks to become an “Austrian writer,” with German as his “only language” and “mother tongue,” while critics constantly racialize him as a Jew and compare his writing to Kafka’s “parasitism” and unhealthy Jewish style.2 “Father” seems to represent classical modernism, struggling to break with the mass and enter elite culture, only to con- front the question of Jewish culture in its own terms, and those of its enemies, everywhere he turns. -

Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka Hartmut Binder

Document generated on 09/25/2021 10:25 p.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, re?daction Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka Hartmut Binder Kafka pluriel : réécriture et traduction Volume 5, Number 2, 2e semestre 1992 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037123ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/037123ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Association canadienne de traductologie ISSN 0835-8443 (print) 1708-2188 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Binder, H. (1992). Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka. TTR, 5(2), 41–105. https://doi.org/10.7202/037123ar Tous droits réservés © TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction — Les auteurs, This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit 1992 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka Hartmut Binder Translation by Iris and Donald Bruce, University of Alberta "Bild, nur Büd"1 [Images, only images] Proverbial sayings are pictorially formed verbal phrases2 whose wording, as it has been handed down, is relatively fixed and whose meaning is different from the sum of its constituent parts. As compound expressions, they are to be distinguished from verbal metaphors; as syntactically dependant constructs, which gain ethical meaning and the status of objects only through their embedding in discursive relationships, they are to be differentiated from proverbs. -

Max Weber and Franz Kafka

Law, Culture and the Humanities http://lch.sagepub.com/ Max Weber and Franz Kafka: A Shared Vision of Modern Law Douglas Litowitz Law, Culture and the Humanities 2011 7: 48 originally published online 7 July 2010 DOI: 10.1177/1743872109355552 The online version of this article can be found at: http://lch.sagepub.com/content/7/1/48 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Association for the Study of Law, Culture and the Humanities Additional services and information for Law, Culture and the Humanities can be found at: Email Alerts: http://lch.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://lch.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from lch.sagepub.com at Chelyabinsk State University on January 11, 2011 LAW, CULTURE AND THE HUMANITIES Article Law, Culture and the Humanities 7(1) 48–65 Max Weber and Franz Kafka: © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: sagepub. A Shared Vision of Modern Law co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1743872109355552 http://lch.sagepub.com Douglas Litowitz Magnetar Capital LLC Abstract Recent scholarship suggests a line of influence from the sociologist Max Weber to the writer Franz Kafka, mediated through the lesser-known figure of Alfred Weber, who was Max’s younger brother and a law professor who served as one of Kafka’s law school examiners. This paper finds textual support for this claim of influence. Indeed, there is an uncanny similarity between Weber’s and Kafka’s writings on law, particularly in their diagnosis of a legitimation crisis at the heart of modern law, and in their suspicion that modern law cannot deliver on its promises.