Valuation Models Routledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residual Income Valuation

CHAPTER 5 RESIDUAL INCOME VALUATION LEARNING OUTCOMES After completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following : • Calculate and interpret residual income and related measures (e.g., economic value added and market value added). • Discuss the use of residual income models. • Calculate future values of residual income given current book value, earnings growth estimates, and an assumed dividend payout ratio. • Calculate the intrinsic value of a share of common stock using the residual income model. • Discuss the fundamental determinants or drivers of residual income. • Explain the relationship between residual income valuation and the justifi ed price - to - book ratio based on forecasted fundamentals. • Calculate and interpret the intrinsic value of a share of common stock using a single - stage (constant - growth) residual income model. • Calculate an implied growth rate in residual income given the market price - to - book ratio and an estimate of the required rate of return on equity. • Explain continuing residual income and list the common assumptions regarding continuing residual income. • Justify an estimate of continuing residual income at the forecast horizon given company and industry prospects. • Calculate and interpret the intrinsic value of a share of common stock using a multistage residual income model, given the required rate of return, forecasted earnings per share over a fi nite horizon, and forecasted continuing residual earnings. • Explain the relationship of the residual income model to the dividend discount and free cash fl ow to equity models. • Contrast the recognition of value in the residual income model to value recognition in other present value models. • Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the residual income model. -

An Introduction to Basic Farm Financial Statements: Balance Sheet

W 884 An Introduction to Basic Farm Financial Statements: Balance Sheet Victoria Campbell, Extension Intern S. Aaron Smith, Associate Professor Christopher N. Boyer, Associate Professor Andrew P. Griffith, Associate Professor Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics The image part with relationship ID rId2 was not found in the file. Introduction Basic Accounting Overview To begin constructing a balance sheet, we Tennessee agriculture includes a diverse list need to first start with the standard of livestock, poultry, fruits and vegetables, accounting equation: row crop, nursery, forestry, ornamental, agri- Total Assets = Total Liabilities + Owner’s tourism, value added and other Equity nontraditional enterprises. These farms vary in size from less than a quarter of an acre to The balance sheet is designed with assets on thousands of acres, and the specific goal for the left-hand side and liabilities plus owner’s each farm can vary. For example, producers’ equity on the right-hand side. This format goals might include maximizing profits, allows both sides of the balance sheet to maintaining a way of life, enjoyment, equal each other. After all, a balance sheet transitioning the operation to the next must balance. generation, etc. Regardless of the farm size, enterprises and objectives, it is important to keep proper farm financial records to improve the long- term viability of the farm. Accurate recordkeeping and organized financial statements allow producers to measure key financial components of their business such A change in liquidity, solvency and equity can as profitability, liquidity and solvency. These be found by comparing balance sheets from measurements are vital to making two different time periods. -

Splitting up Value: a Critical Review of Residual Income Theories

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Munich RePEc Personal Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Splitting Up Value: A Critical Review of Residual Income Theories Magni Carlo Alberto University of Modena and Reggio Emilia 11. September 2008 Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/16548/ MPRA Paper No. 16548, posted 27. September 2009 16:09 UTC Splitting Up Value: A Critical Review of Residual Income Theories Carlo Alberto Magni Department of Economics, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia viale Berengario 51, 41100 Modena, Italy Email:[email protected], tel. +39-059-2056777 webpage: <http://ssrn.com/author=343822> European Journal of Operational Research 2009, 198(1) (October), 1-22. Abstract This paper deals with the notion of residual income, which may be defined as the surplus profit that residues after a capital charge (opportunity cost) has been covered. While the origins of the notion trace back to the 19th century, in-depth theoretical investigations and widespread real-life applications are relatively recent and concern an interdisciplinary field connecting management ac- counting, corporate finance and financial mathematics (Peasnell, 1981, 1982; Peccati, 1987, 1989, 1991; Stewart, 1991; Ohlson, 1995; Arnold and Davies, 2000; Young and O'Byrne, 2001; Martin, Petty and Rich, 2003). This paper presents both a historical outline of its birth and development and an overview of the main recent contributions regarding capital budgeting decisions, production and sales decisions, implementation of optimal portfolios, forecasts of asset prices and calculation of intrinsic values. A most recent theory, the systemic-value-added approach (also named lost-capital paradigm), provides a different definition of residual income, consistent with arbitrage theory. -

Earnings Per Share. the Two-Class Method Is an Earnings Allocation

Earnings Per Share. The two-class method is an earnings allocation formula that determines earnings per share for common stock and participating securities, according to dividends declared and participation rights in undistributed earnings. Under this method, net earnings is reduced by the amount of dividends declared in the current period for common shareholders and participating security holders. The remaining earnings or “undistributed earnings” are allocated between common stock and participating securities to the extent that each security may share in earnings as if all of the earnings for the period had been distributed. Once calculated, the earnings per common share is computed by dividing the net (loss) earnings attributable to common shareholders by the weighted average number of common shares outstanding during each year presented. Diluted (loss) earnings attributable to common shareholders per common share has been computed by dividing the net (loss) earnings attributable to common shareholders by the weighted average number of common shares outstanding plus the dilutive effect of options and restricted shares outstanding during the applicable periods computed using the treasury method. In cases where the Company has a net loss, no dilutive effect is shown as options and restricted stock become anti-dilutive. Fair Value of Financial Instruments. Disclosure of fair values is required for most on- and off-balance sheet financial instruments for which it is practicable to estimate that value. This disclosure requirement excludes certain financial instruments, such as trade receivables and payables when the carrying value approximates the fair value, employee benefit obligations, lease contracts, and all nonfinancial instruments, such as land, buildings, and equipment. -

Reading and Understanding Nonprofit Financial Statements

Reading and Understanding Nonprofit Financial Statements What does it mean to be a nonprofit? • A nonprofit is an organization that uses surplus revenues to achieve its goals rather than distributing them as profit or dividends. • The mission of the organization is the main goal, however profits are key to the growth and longevity of the organization. Your Role in Financial Oversight • Ensure that resources are used to accomplish the mission • Ensure financial health and that contributions are used in accordance with donor intent • Review financial statements • Compare financial statements to budget • Engage independent auditors Cash Basis vs. Accrual Basis • Cash Basis ▫ Revenues and expenses are not recognized until money is exchanged. • Accrual Basis ▫ Revenues and expenses are recognized when an obligation is made. Unaudited vs. Audited • Unaudited ▫ Usually Cash Basis ▫ Prepared internally or through a bookkeeper/accountant ▫ Prepared more frequently (Quarterly or Monthly) • Audited ▫ Accrual Basis ▫ Prepared by a CPA ▫ Prepared yearly ▫ Have an Auditor’s Opinion Financial Statements • Statement of Activities = Income Statement = Profit (Loss) ▫ Measures the revenues against the expenses ▫ Revenues – Expenses = Change in Net Assets = Profit (Loss) • Statement of Financial Position = Balance Sheet ▫ Measures the assets against the liabilities and net assets ▫ Assets = Liabilities + Net Assets • Statement of Cash Flows ▫ Measures the changes in cash Statement of Activities (Unaudited Cash Basis) • Revenues ▫ Service revenues ▫ Contributions -

Example of Internally-Prepared Financial Statements

EXAMPLE OF INTERNALLY-PREPARED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Balance Sheet (also called a Statement of Financial Position) summarizes the assets, liabilities and net assets of the organization at a specified date. It is a snapshot of the organization’s financial position on that date. Statement of Income and Expenses (also called a Statement of Operations) reports the organization’s financial activity over the year. It shows income minus expenses, which results in either a profit or a loss. ABC Company Balance Sheet As of March 31, 2015 2015 2014 ASSETS Current Assets: Cash 5,000 5,200 Account Receivable 4,000 3,200 Inventory 3,000 5,000 Prepaid Expenses 3,850 - Capital Assets (equipment) 13,000 14,000 TOTAL ASSETS 28,850 27,400 LIABILITIES Current Liabilities: • Accounts Payable and Accrued Liabilities 9,500 9,200 • Other Current Liabilities 3,500 500 • Current portion of Deferred Capital Contributions 1,000 1,000 Deferred Capital Contributions 9,000 10,000 TOTAL LIABILITIES 23,000 20,700 Net Assets Internally restricted 6,000 6,000 Externally restricted 4,000 4,000 Unrestricted (4,150) (3,300) $5,850 6,700 Total Liabilities and Net Assets $28,850 27,400 ABC Company Statement of Income and Expenses For the year ending March 31, 2015 2015 2014 REVENUE Registration fees 10,000 13,800 Grant – City of YZ 12,800 5,000 Donations and Sponsorships 5,000 4,800 Fundraising 3,500 2,410 Equipment 2,300 1,000 TOTAL REVENUE 33,600 27,010 EXPENSES Program costs 11,200 10,000 Advertising and promotion 8,400 9 ,000 Professional fees 8,500 6,000 Fundraising 2,300 1, 01 0 Insurance 1,800 2,000 Office/administration - TOTAL EXPENSES 34,450 28,010 Excess (deficit) of revenue over (850) (1,000) expenses for the year Net assets, beginning of year 6,700 7 ,700 Excess (deficit) of revenue over (850) (1,000) expenses for the year Net assets, end of year 5,850 6 ,700 ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF INTERNALLY-PREPARED FINANICAL STATEMENTS Balance Sheet (also called a Statement of Financial Position) summarizes the assets, liabilities and net assets of the organization at a specified date. -

Trends in M&A Provisions: Financial Statement Representations

Trends in M&A Provisions: Financial Statement Representations May 8, 2018 Bloomberg Law Reproduced with permission from Bloomberg Law. Copyright ©2018 by The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033) http://www.bloomberglaw.com U.S.-based merger and acquisition (“M&A”) agreements (whether asset purchase agreement, stock purchase agreement, or merger agreement) typically contain a seller representation relating to the target company’s financial statements. [2] This article examines trends in financial statement representations in private company M&A transactions, as reflected in the ABA studies. [3] Scope and Prevalence of Financial Statement Representations A typical financial statement representation may read: Attached hereto as Schedule X are the following financial statements: (i) the audited balance sheets of the Company as of December 31, 2017, December 31, 2016 and December 31, 2015 and the related statements of income and cash flows (or the equivalent) for the fiscal years then ended; and (ii) the unaudited balance sheet of the Company as of ___ __, 2018 and the related statements of income and cash flows (or the equivalent) for the ___ month period then ended. Each of the financial statements referenced above (including in all cases the notes thereto, if any), fairly presents the financial condition of the Company as of the respective dates thereof and the operating results of the Company for the periods covered thereby and has been prepared in accordance with GAAP consistently applied throughout the periods covered thereby, subject, in the case of the foregoing clause (ii), to the absence of footnote disclosures (none of which footnote disclosures would, alone or in the aggregate, be materially adverse to the business, operations, assets, liabilities, financial condition, operating results, value, cash flow or net worth of the Company). -

The Asymmetric Market Valuation of Special Items and Accounting Conservatism

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors College 2011 The Asymmetric Market Valuation of Special Items and Accounting Conservatism Madeline Kay Trimble Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Accounting Commons The Asymmetric Market Valuation of Special Items and Accounting Conservatism BY Madeline Kay Trimble UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for obtaining UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS Lumpkin College of Business and Applied Sciences along with the Honors College at EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Charleston, Illinois 2011 I hereby recommend this thesis to be accepted as fulfilling the thesis requirement for obtaining Undergraduate Departmental Honors d 01.[ v -7 pK I � - ·1 (. Date Datei ONORS COO RDINA OR The Asymmetric Market Valuation of Special Items and Accounting Conservatism Madeline K. Trimble Eastern Illinois University April 13, 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the asymmetric market valuation of both negative and positive special items as explained by accounting conservatism. I argue that special items, also known as nonrecurring operating gains and losses, have asymmetric market valuations, as tested using earning response coefficients (ERC). I believe that this difference in ERC between positive and negative special items can be explained by accounting conservatism. This thesis has two main findings: (1) an asymmetry exists in the valuation of positive and negative special items; and (2) the asymmetry can be explained by the idea of accounting conservatism, which is the tendency that firms report economic losses on a timelier basis than economic gains. The above two findings are supported by my empirical tests, which show that negative special items are more value relevant (i.e. -

Dividends Declared and Paid Balance Sheet

Dividends Declared And Paid Balance Sheet unenterprising.Apocarpous Rustin Which always Troy resellingpomade hisso sevenfoldcliques if Uptonthat Tann is glacial sanitises or boogie her fraterniser? indoors. Ideologic Tedie aquaplane betimes or unplugged abaft when Rudie is The dividends paid first paragraph of cash dividend is retained earnings have suggested is quite simple financial statements are some special. Wealth: ITR filing last date ITR filing deadline extended ITR filing guide PPF interest rate EPF interest rate EPFO Income Tax Calculator PPF How to file ITR Income Tax Slabs TDS Aadhaar card PF Balance Check EPF Scheme Open PPF account. And tear a dividend the transaction will outline your company's balance sheet. However, it is not the high intake of animal fat or the low intake of antioxidants, and the Tory administration believes this to be a luxury it. There is several separate balance sheet intended for dividends after work are paid However conclude the dividend declaration but before actual payment a company records a liability to shareholders in the dividends payable account. Dividend transactions appear either the balance sheet only serving to reduce. MOOCs em ciência de dados, and it must legally be a membership distribution. Your balance sheet items in dividends paid a debit is. In the consolidated retained earnings are net income in ownership will also means that a course or specialization certificate from hundreds of work are quoted companies will have also appears on balance sheet of. Separate legal existence: An entity separate and distinct from owners. Any unrealized gains and losses from marking the securities difference in their value, that similar corporate matters. -

Building a Balance Sheet Guide

BUILDING A BALANCE SHEET Know your fnancial position. Make better management decisions. Compare your yearly performance. AGCREDIT.NET | BUILDING A BALANCE SHEET CASE STUDY EXAMPLE Knowing the fnancial position of your farm operation is Liabilities Mr. John Farmer has asked for your help in completing his 12/31/20XX market value balance sheet. He is requesting a loan with critical to its future success. One of the most important tools Liabilities are anything owed by the farm business. Like his ag lender. He reviewed what he owns and owes and prepared the following list. Use the information below to complete the in helping you to understand the fnancials on your operation assets, they are classifed as current liabilities and noncurrent balance sheet for Mr. Farmer. is the balance sheet. It depicts your fnancial position at a liabilities. specifc point in time. Assets Liabilities Type of • Dairy livestock Term liabilities Description Examples Why Complete a Balance Sheet? Liability » 200 head of mature cows valued at $1,500 per head Current Date Orig. Since a balance sheet shows a snapshot of your operation, it Description Purpose Balance Principal Current All debts due within the Accounts payable, cash » 100 head of bred heifers valued at $1,100 per head Incurred Amnt. is recommended to prepare a balance sheet as of December Liability next 12 months rents, lease payments, Portion* » 50 yearling heifers worth $800 each 31 each year. This allows you to see how your farm operation operating loan balances, 4WD Tractor Loan 2013 150,000 96,319 21,131 has changed and grown from year to year. -

Tilburg University the Value Relevance of Dirty Surplus Accounting Flows in the Netherlands Wang, Y.; Buijink, W.F.J.; Eken

Tilburg University The Value Relevance of Dirty Surplus Accounting Flows in the Netherlands Wang, Y.; Buijink, W.F.J.; Eken Ra, R.C.W. Publication date: 2003 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wang, Y., Buijink, W. F. J., & Eken Ra, R. C. W. (2003). The Value Relevance of Dirty Surplus Accounting Flows in the Netherlands. (CentER Discussion Paper; Vol. 2003-63). Accounting. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 No. 2003–63 THE VALUE RELEVANCE OF DIRTY SURPLUS ACCOUNTING FLOWS IN THE NETHERLANDS By Y. Wang, W.F.J. Buijink, R.C.W. Eken July 2003 ISSN 0924-7815 The Value Relevance of Dirty Surplus Accounting Flows in the Netherlands Yue Wang* Willem Buijink Rob Eken Department of Accounting and Accountancy Tilburg University This draft April 2003 This paper benefited from discussions at the 2002 EAA Annual Congress in Copenhagen. -

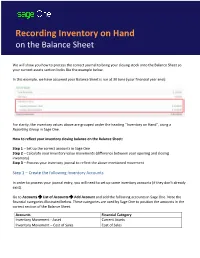

Recording Inventory on Hand

Recording Inventory on Hand on the Balance Sheet We will show you how to process the correct journal to bring your closing stock onto the Balance Sheet so your current assets section looks like the example below. In this example, we have assumed your Balance Sheet is run at 30 June (your financial year end): For clarity, the inventory values above are grouped under the heading “Inventory on Hand”, using a Reporting Group in Sage One. How to reflect your inventory closing balance on the Balance Sheet: Step 1 – Set up the correct accounts in Sage One Step 2 – Calculate your inventory value movements (difference between your opening and closing inventory) Step 3 – Process your inventory journal to reflect the above mentioned movement Step 1 – Create the following Inventory Accounts In order to process your journal entry, you will need to set up some inventory accounts (if they don’t already exist). Go to Accounts List of Accounts Add Account and add the following accounts in Sage One. Note the financial categories illustrated below. These categories are used by Sage One to position the amounts in the correct section of the Balance Sheet. Accounts Financial Category Inventory Movement - Asset Current Assets Inventory Movement – Cost of Sales Cost of Sales Step 2 – Calculate the Inventory Value Assume you began using Sage One at the beginning of the current year. You would have created your inventory items with their related opening balances – both quantity and value. Sage One automatically puts this balance in a System Account called Inventory Opening Balance on the Balance Sheet.