Studies in Applied Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

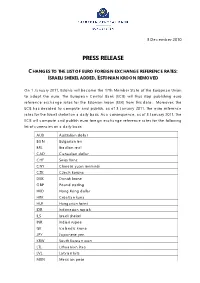

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: the Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series REGIONAL AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION IN ASIA Zsolt Darvas No. 712 April 2017 Asian Development Bank Institute Zsolt Darvas is senior fellow at Bruegel and senior research Fellow at the Corvinus University of Budapest. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Darvas, Z. 2017. Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: The Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia. ADBI Working Paper 712. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/regional-and-global-financial-safety-nets Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Paper prepared for the Conference on Global Shocks and the New Global/Regional Financial Architecture, organized by the Asian Development Bank Institute and S. -

Baltic Monetary Regimes in the Xxist Century

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Viksnins, George J. Article — Digitized Version Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Viksnins, George J. (2000) : Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 35, Iss. 5, pp. 213-218 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/40777 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu EU ENLARGEMENT member states, the candidates should expect the dangers of inaction are even greater because the enlargement to be in a state of fluidity. existing member states may use their veto on • Second, the fact that uncertainty cannot be accession of new members to protect their broader interests. -

On Israel's "Hyperinflation"

SAE./No.127/September 2018 Studies in Applied Economics ON ISRAEL'S "HYPERINFLATION" Tal Boger Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise On Israel's \Hyperinflation” Tal Boger∗ Johns Hopkins University Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise. September 2018. Abstract Affected by the worldwide ”Stagflation” of the 1970s caused by sharp oil price rises in 1973 and 1979, Israel experienced elevated inflation rates in the 1970s. These inflation rates not only continued but also accelerated into the 1980s, as Israel saw its inflation hit triple digits at the turn of the decade. This inflation worsened, and peaked in 1984 and 1985. Noticing the sharply rising in- flation rates in Israel, many journalists and academics dubbed Israel's bout of inflation a hyperinflation, and have questioned its exclusion from the Hanke-Krus World Hyperinfla- tion Table. However, an analysis of Israel's CPI data - as reported by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics - shows that Israel's inflation rates fell short of hyperinflation by a sizable margin. Analyzing Israel's primary CPI data, we find conclusive evidence that Israel did not hyperinflate in the 1980s, despite many credible analyses to the contrary. Keywords: Hyperinflation, Israeli inflation 1. Introduction On October 14, 1984, Hobart Rowen wrote an article for The Washington Post titled \Israel's Hyperinflation: Ravaged State of Economy a Threat to Israel's Survival." In the article, Rowen writes that \[Israel] now must deal with the reality of a hyperinflation that is running over 400 percent, and in a few days may be measured at the incomprehensible level ∗Tal Boger is a senior at Beth Tfiloh Dahan Community High School. -

Estonia in the Eurozone – a Strategic Success

oswCommentary issue 53 | 20.06.2011 | Centre for eastern studies Estonia in the eurozone y – a strategic success ENTAR m Paweł Siarkiewicz Com es C The adoption of the euro in January 2011 topped off Estonia’s integration policy. In the opinion of Estonian politicians, this country has never been so secure and stable in its history. Tallinn sees the introduction of the tudies euro primarily in the political context as an entrenchment of the Estonian s presence in Europe. The process of establishing increasingly close rela- tions with Western European countries, which the country has consisten- astern tly implemented since it restored independence in 1991, has been aimed e at severing itself its Soviet past and at a gradual reduction of the gap existing between Estonia and the best-developed European economies. The Estonian government also prioritises the enhancement of co-operation as part of the EU and NATO as well as its principled fulfilment of the Centre for country’s undertakings. It sees these as important elements for building the country’s international prestige. y The meeting of the Maastricht criteria at the time of an economic slump ENTAR m and the adoption of the euro during the eurozone crisis proved the deter- mination and efficiency of the government in Tallinn. Its success has been Com based on strong support from the Estonian public for the pro-European es C (integrationist) policy of Estonia: according to public opinion polls, appro- ximately 80% of the country’s residents declare their satisfaction with EU membership, while support for the euro ranges between 50% and 60%. -

Republic of Estonia (Banking and Cürbency Befobm) 7 % Loan, 1927

[Distributed to the Council and C. 186. M. 60. 1928. ii the Members of the League.] (F. 514.) Geneva, August 3rd, 1928. LEAGUE OF NATIONS REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA (BANKING AND CÜRBENCY BEFOBM) 7 % LOAN, 1927 FIRST ANNUAL REPORT BY THE TRUSTEE covering the period from June 15lh, 1927, to June 30th, 1928. I ntroduction . In conformity with the decision of the Council of September 15th, 1927. I have the honour to submit to the Council of the League of Nations my first annual report as Trustee for the " Republic of Estonia (Banking and Currency Reform) 7 % Loan. 1927 ”, it may be useful to give in this first report a somewhat detailed description of the execution of the scheme and of the duties of the Trustee. The essential features of the Estonian banking and currency reform, on which the Estonian Government and the financial experts of the League had already been working for some time, are contained in the Protocol signed at Geneva on December 10th. 1926. by the Estonian Minister of Finance, and approved by the Council on the same day. As provided for in this Protocol, the following laws were passed by the Estonian Parliament early in May 1927. viz., (1) the Eesti Pank Statutes Law, (2) the Monetary Law of Estonia, (3) the Law to terminate the Issue of Treasury and " Change ” Notes, and (4) the Foreign Loan Law 1. Thereupon, it was permissible to open negotiations for the loan which was to be issued under the auspices of the League and which was to produce an effective net yield of £1.350,000. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 23.7.2013 COM(2013) 540 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area EN EN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Twelfth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area 1. INTRODUCTION Since the adoption of the euro by Estonia on 1 January 2011, the euro area consists of seventeen EU Member States. Among the remaining eleven Member States, nine Member States are expected to adopt the euro once the necessary conditions are fulfilled. Denmark and the United Kingdom have a special "opt-out"-status and are not committed to adopt the euro. This report assesses the state of play of the practical preparations for introducing the euro in Latvia and evaluates the progress made in preparing the changeover related communication campaign. Following the Council decision from 9 July 2013 concluding that the necessary conditions for euro adoption are fulfilled, Latvia will adopt the euro on 1 January 2014 ("€- day"). The conversion rate between the Latvian lats and the euro has been irrevocably fixed at 0.702804 Latvian lats to one euro. 2. STATE OF PLAY OF THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE CHANGEOVER IN LATVIA Latvia will be the sixth of the group of Member States which joined the EU in 2004 to adopt the euro. Latvia's original target date of 1 January 2008 foreseen in the Action Plan for Implementation of the Single European Currency of 1 November 2005 was subsequently reconsidered. -

Bank of Estonia (Eesti Pank) Act – Riigi Teataja

Bank of Estonia (Eesti Pank) Act – Riigi Teataja https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/513042015009/consolide Issuer: Riigikogu Type: act In force from: 29.03.2015 In force until: In force Translation published: 13.04.2015 Bank of Estonia (Eesti Pank) Act Passed 18.05.1993 RT I 1993, 28, 498 Entry into force 18.06.1993 Chapter 1 General Provisions § 1. Legal foundations of the Bank of Estonia(Eesti Pank) (1) The Bank of Estonia (Eesti Pank) - hereinafter, ‘the Bank of Estonia’ - is the central bank of the Republic of Estonia and a member of the European System of Central Banks. The Bank of Estonia is the legal successor to the Bank of Estonia which was established as the central bank of the Republic of Estonia in 1919. [RT I 2006, 29, 219 - entry into force 08.07.2006] (2) The Bank of Estonia is a legal person with its own Statute, seal, coat of arms and other insignia permitted by the law. (3) The Bank of Estonia operates pursuant to the Constitution of the Republic of Estonia, the Constitution of the Republic of Estonia Amendment Act, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank, legislation of the European Central Bank, this Act, other Acts and its Statute. [RT I 2010, 22, 108 - entry into force 01.01.2011] (4) The legal status of the Bank of Estonia may only be changed by the passage of a Bank of Estonia Act Amendment Act. -

Estonian Way to Liberal Economic System

Center for Social & Economic Research ESTONIAN WAY TO LIBERAL ECONOMIC SYSTEM Jarosław Bauc CASE, Center for Social & Economic Research Warsaw, Poland Warsaw, April 1995 Materials published in this series have a character of working papers which can be a subject of further publications in the future. The views and opinions expressed here reflect Authors' point of view and not necessary those of CASE . Paper was prepared for the project: "Economic Reforms in the former USSR" (Reformy gospodarcze na terenie dawnego ZSRR), financed by the Committee of Scientific Reasearch (Komitet Badań Naukowych). CASE Research Foundation, Warsaw 1995 ISBN 83-86296-34-8 Editor: CASE - Center for Social & Economic Research 00-585 Warszawa, Bagatela 14 tel/fax (48-2) 628 65 81; tel/fax (48-22) 29 43 83 Estonian Way to Liberal Economic System 1. Starting point of reform and general features of development Estonia 1 has adopted the one of the most radical programs of stabilization and transformation amongst not only the former Soviet Union countries but among previously centrally planned economies as well. The commodity and service markets were balanced mainly through the price liberalization and introduction of the internally convertible national currency. This was supplimented with the austerity in public consumption and surpluss in the state budget. The changes were also associated with a radical shift in the foreign trade rearientation. The economy that previously was oriented to almost costless recources from the former Soviet Union and work mostly for the Soviet "markets" seems to be very well adjusted to western markets and broad participation in the world economy. -

Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia

ISSN 1725-3217 Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia EUROPEAN ECONOMY 3|2013 Economic and Financial Affairs The European Economy series contains important reports and communications from the Commission to the Council and the Parliament on the economic situation and developments, such as the European economic forecasts and the Public finances in EMU report. Unless otherwise indicated the texts are published under the responsibility of the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission to which enquiries should be addressed. Legal notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this publication, or for any errors which, despite careful preparation and checking, may appear. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN 978-92-79-28535-6 doi: 10.2765/40058 © European Union, 2013 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia EUROPEAN ECONOMY European Economy N° 3/2013 ABBREVIATIONS LV Latvia EA Euro area EU-27 European Union, 27 Member States EU-25 European Union, 25 Member States before 2007 (i.e. EU-27 excl. BG and RO) EU-15 European Union, 15 Member States before 2004 EUR Euro ECU European currency unit LVL Latvian lats USD US dollar SDR Special Drawing Rights AMR Alert Mechanism Report BoL Bank of Latvia BoP Balance of Payments -

Challenges Facing Estonian Economy in the European Union

Vahur Kraft: Challenges facing Estonian economy in the European Union Speech by Mr Vahur Kraft, Governor of the Bank of Estonia, at the Roundtable “Has social market economy a future?”, organised by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Tallinn, 19 August 2002. * * * A. Introduction, review of the early 1990s and comparison with the present day First of all, allow me to thank Konrad Adenauer Foundation for the organisation of this interesting roundtable and for the honourable invitation to speak about “Challenges of Estonian economy in the European Union”. Today’s event shows yet again how serious is the respected organisers’ interest towards the EU applicant countries. I personally appreciate highly your support to our reforms and convergence in the society and economy. From the outside it may seem that the transformation and convergence process in Estonia has been easy and smooth, but against this background there still exist numerous hidden problems. One should not forget that for two generations half of Europe was deprived of civil society, private ownership, market economy. This is truth and it has to be reckoned with. It is also clear that the reflections of the “shadows of the past” can still be observed. They are of different kind. If people want the state to ensure their well-being but are reluctant to take themselves any responsibility for their own future, it is the effect of the shadows of the past. If people are reluctant to pay taxes but demand social security and good roads, it is the shadow of the past. In brief, if people do not understand why elections are held and what is the state’s role, it is the shadow of the past. -

Venezuela's Tragic Meltdown Hearing

VENEZUELA’S TRAGIC MELTDOWN HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 28, 2017 Serial No. 115–13 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–831PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 12:45 May 02, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_WH\032817\24831 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. YOHO, Florida DINA TITUS, Nevada ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois NORMA J.