An Analysis of the Bassoon and Its Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Recital

Student Recital Room 106 Schaefer Fine Arts Center Gustavus Adolphus College Saturday, July 21st, 2007 9:00:AM Program » Quintet Op. 77 in G Major Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) Angela Xie, violin Julia Johnson, violin Elizabeth Johnson, violin Bjorn Hovland, cello Matt Minteer, bass Bourrie 1 from Suite 43 inC Major Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) John Sholund, bass guitar . Preguntale a Las Estrellas Latin American Folk Song Arr, Edward Kilenyi Christine Hoffman, mezzo-soprano Galina Zisk, piano Intorno all’idol mio Marco Antonio Cesti z (1623-1669) Christine Mennicke, soprano Galina Zisk, piano a a i a We ask that all members of the audience refrain from photographing or recording the performance. Please be sure that a all cell phones, beepers, alarms, and similar devices are turned off. cm A high-fidelity recording of this performance may be ordered. A @ brochure will be available following the performance. = You are invited to attend the next events of a The 2007 Lutheran Summer Music Festival: = Student Recitals a Christ Chapel & Room 214, and Room 106 Schaefer Fine Arts Center = Gustavus Adolphus College = Saturday, July 21st, 2007 10:30 AM, 12:00 PM, and 2:30 PM | al Jazz Ensemble Concert Bjérling Recital Hall «a Schaefer Fine Arts Center e Gustavus Adolphus College Saturday, July 21st, 2007 ea 1:00 PM e Festival Orchestra Concert e Christ Chapel a Gustavus Adolphus College Saturday, July 21st, 2007 e 7:00 PM = e This concert is the thirty-eighth event of = Lutheran Summer Music Festival 2007 = = «a «= ee se «= LUTHERAN. UMIME Ro ~~__ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Collegium Musicum S. -

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

FOMRHI Quarterly

il£jia Dal Cortivc Quarterly No. €><4- Jxxly 199 1 FOMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 64 2 Bulletin Supplement 4 MEMBERSHIP LIST Supplement 63 CO Ivl _vlT_J 1ST ICATI01ST S 1044 Review. A.C.I.M.V. (Larigot) Wind Instrument Makers and their Catalogues No. 1: Martin Freres & FamilJe J. Montagu 5 1045 John Paul: an appreciation J. Barnes 6 1046 [Letter to J. M.] D. J. Way 7 1047 On teaching wood to sing D. J. Way 8 1048 Reconstructing Mersenne's basson and fagot G. Lyndon-Jones & P. Harris 9 1049 Praetorius' "Basset: Nicolo" - "lang Strack basset zu den Krumhomer", or "Centaur, mythical beast"? C. Foster 20 1050 Paper organ pipes D. S. Gill 26 10S1 The longitudinal structure of the "Bizey Boxwood Flute" M. Brach 30 1052 Dutch recorders and transverse flutes of the 17th and 18th century J. Bouterse 33 1053 Some English viol belly shapes E. Segerman 38 1054 Mersenne's monochord B. Napier- Hemy 42 1055 Essays of Pythagorean system: 1. primary concepts, 2. two-dimensional syntax F. Raudonikas 44 1056 Evidence of historical temperament from fretted clavichords P. Bavington & M. Hellon 55 1057 A signed Mietke harpsichord A. Kilstrom 59 FELLOWSHIP OF MAKERS AND RESEARCHERS OF HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS Hon. Sec.: J. Montagu, c/o Faculty of Music, St. Aldate's Oxford OX1 1DB, U.K. Bull. 64, p. 2 FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESEARCHERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS Bulletin 64 July, 1991 Well, last time was a bit of a shock. I expected it to be late, as I'd warned you it would be, but not as late as it was. -

June 2015 Broadside

T H E A T L A N T A E A R L Y M U S I C ALLIANCE B R O A D S I D E Volume XV # 4 June, 2015 President’s Message Are we living in the Renaissance? Well, according to the British journalist, Stephen Masty, we are still witnessing new inventions in musical instruments that link us back to the Renaissance figuratively and literally. His article “The 21st Century Renaissance Inventor” [of musical instruments], in the journal “The Imaginative Conservative” received worldwide attention recently regard- ing George Kelischek’s invention of the “KELHORN”. a reinvention of Renaissance capped double-reed instruments, such as Cornamuse, Crumhorn, Rauschpfeiff. To read the article, please visit: AEMA MISSION http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2015/05/the-21st-centurys-great-renaissance-inventor.html. It is the mission of the Atlanta Early Music Alli- Some early music lovers play new replicas of the ance to foster enjoyment and awareness of the histor- Renaissance instruments and are also interested in playing ically informed perfor- the KELHORNs. The latter have a sinuous bore which mance of music, with spe- cial emphasis on music makes even bass instruments “handy” to play, since they written before 1800. Its have finger hole arrangements similar to Recorders. mission will be accom- plished through dissemina- tion and coordination of Yet the sound of all these instruments is quite unlike that information, education and financial support. of the Recorder: The double-reed presents a haunting raspy other-worldly tone. (Renaissance? or Jurassic?) In this issue: George Kelischek just told me that he has initiated The Capped Reed Society Forum for Players and Makers of the Crumhorn, President ’ s Message page 1 Cornamuse, Kelhorn & Rauschpfeiff. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

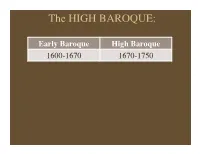

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Laker Drumline Marching Bass Drum Technique

Laker Drumline Marching Bass Drum Technique This packet is intended to define a base framework of knowledge to adequately play a marching bass drum at the collegiate level. We understand that every high school drumline has its own approach to technique, so it’s crucial that ALL prospective members approach their hands with a fresh mind and a clean slate. Mastery of the following concepts & terminology will dramatically improve your experience during the audition process and beyond. Happy drumming! APPROACH The technique outlined in this packet is designed to maximize efficiency of motion and sound quality. It is necessary to use a high velocity stroke while keeping your grip and your muscles relaxed. Keep these key points in mind as you work to refine the music in this packet. Tension in your upper body, lack of oxygen to your muscles, and squeezing the stick are good examples of technique errors that will hinder your ability to achieve the sound quality, efficiency, and control that we strive for. GRIP Fulcrum Place the mallet perpendicularly across the second segment of your index finger. Place your thumb on the mallet so that the thumbnail is directly across from your index finger. ** This is the essential point of contact between your hands and the stick. It should be thought of as the primary pressure point in your fingers and pivot point on the stick. The entire pad of your thumb should remain in contact with the mallet at all times. As a bass drummer, about 60% of the pressure in your hands should lie in the fulcrum. -

Kimberlie Rose Dillon Oboe & English Horn Teamdillonmusic.Wordpress.Com

Kimberlie Rose Dillon Oboe & English Horn teamdillonmusic.wordpress.com I. Education & Training McLennan Community College | Teacher Certification in Early Childhood-Grade 12 Music 2013 Baylor University | Teaching Certificate in Higher Education 2012 Baylor University | Master of Music Degree in Oboe Performance 2012 Oboe Professor: Doris DeLoach, DMA University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD) | Bachelor of Music Degree in Oboe Performance 2010 Oboe Instructor: Laurie Van Brunt Jeanne Inc. | Oboe Gouger Assembly & Maintenance Workshop 2009 Other Primary Teachers Julie Gramolini Williams | Minnesota Orchestra 2015-Present Susan Tomkiewicz, DMA | Luther College 2005-2006 Jennifer Gookin, DMA | Luther College 1999-2005 II. Employment UMD Fine Arts Academy | Community Music Teaching Specialist 2014-Present teach weekly private oboe lessons to middle and high school students Rock Hill Community Church | Administrator 2013-2015 assisted pastoral staff with organizational functions coordinated volunteer schedules, supported bookkeeping efforts, and helped with event planning Waco Baptist Academy | Preschool-Grade 6 General Music Educator 2012-2013 taught Prekindergarten – Grade 6 general music classes and directed school performances Baylor University Golden Wave Marching Band | Administrative Assistant 2012 supported the Golden Wave Marching Band Director by serving in an administrative role Baylor University Fine Arts Library | Student Assistant 2011-2012 assisted patrons in research and checking out materials and shelved books and scores Baylor University School of Music | Graduate Assistant 2010-2012 co-instructed oboe methods, taught secondary oboe lessons, and coached chamber music ensembles coordinated student music recitals and performed secretarial tasks III. Performance Experience Ensembles Mesabi Symphony Orchestra, Sub. Oboe & English Horn 2016-Present, 2013 Itasca Symphony Orchestra, Sub. Oboe & English Horn 2013-Present Lake Superior Chamber Orchestra, Sub. -

The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions J. Wayne Johnson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, J. Wayne, "The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2804. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IDENTIFICATION OF BAS~C PROBLEMS FOUND IN THE BASSOON PARTS OF A SELECTED GROUP OF BAND COMPOSITI ONS by J. Wayne Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the r equ irements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Music Education UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan , Ut a h 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BASSOON 3 THE I NSTRUMENT 20 Testing the bassoon 20 Removing moisture 22 Oiling 23 Suspending the bassoon 24 The reed 24 Adjusting the reed 25 Testing the r eed 28 Care of the reed 29 TONAL PROBLEMS FOUND IN BAND MUSIC 31 Range and embouchure ad j ustment 31 Embouchure · 35 Intonation 37 Breath control 38 Tonguing 40 KEY SIGNATURES AND RELATED FINGERINGS 43 INTERPRETIVE ASPECTS 50 Terms and symbols Rhythm patterns SUMMARY 55 LITERATURE CITED 56 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. -

Leonard Bernstein's MASS

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, April 30, at 8:00 Friday, May 1, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 2, at 8:00 Sunday, May 3, at 2:00 Leonard Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers* Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin Texts from the liturgy of the Roman Mass Additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein For a list of performing and creative artists please turn to page 30. *First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. These performances are made possible in part by the generous support of the William Penn Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Presser Foundation. 28 I. Devotions before Mass 1. Antiphon: Kyrie eleison 2. Hymn and Psalm: “A Simple Song” 3. Responsory: Alleluia II. First Introit (Rondo) 1. Prefatory Prayers 2. Thrice-Triple Canon: Dominus vobiscum III. Second Introit 1. In nomine Patris 2. Prayer for the Congregation (Chorale: “Almighty Father”) 3. Epiphany IV. Confession 1. Confiteor 2. Trope: “I Don’t Know” 3. Trope: “Easy” V. Meditation No. 1 VI. Gloria 1. Gloria tibi 2. Gloria in excelsis 3. Trope: “Half of the People” 4. Trope: “Thank You” VII. Mediation No. 2 VIII. Epistle: “The Word of the Lord” IX. Gospel-Sermon: “God Said” X. Credo 1. Credo in unum Deum 2. Trope: “Non Credo” 3. Trope: “Hurry” 4. Trope: “World without End” 5. Trope: “I Believe in God” XI. Meditation No. 3 (De profundis, part 1) XII. -

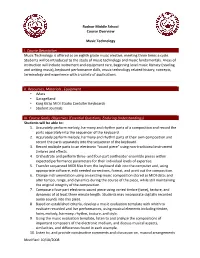

Music Tech-1

Radnor Middle School Course Overview Music Technology I. Course Description Music Technology is offered as an eighth grade music elective, meeting three times a cycle. Students will be introduced to the study of music technology and music fundamentals. Areas of instruction will include instrument and equipment care, beginning level music literacy (reading and writing music), keyboard performance skills, music technology related history, concepts, terminology and experience with a variety of applications. II. Resources, Materials , Equipment • iMacs • GarageBand • Korg K61p MIDI Studio Contoller Keyboards • Student Journals III. Course Goals, Objectives (Essential Questions, Enduring Understandings) Students will be able to: 1. Accurately perform melody, harmony and rhythm parts of a composition and record the parts separately into the sequencer of the keyboard. 2. Accurately perform melody, harmony and rhythm parts of their own composition and record the parts separately into the sequencer of the keyboard. 3. Record multiple parts to an electronic “sound piece” using non-traditional instrument timbres and effects. 4. Orchestrate and perform three- and four-part synthesizer ensemble pieces within expected performance parameters for their individual levels of expertise. 5. Transfer sequenced MIDI files from the keyboard disk into the computer and, using appropriate software, edit needed corrections, format, and print out the composition. 6. Change instrumentation using an existing music composition stored as MIDI data; and alter tempo, range, and dynamics during the course of the piece, while still maintaining the original integrity of the composition. 7. Compose a four-part electronic sound piece using varied timbre (tone), texture, and dynamics of at least three minute length. Students may incorporate digitally recorded audio sounds into this piece.