Smallholder Pig Value Chain Assessment in Uganda: Results from Producer Focus Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Education,Science,Technology And

Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports Structure of Submission QUARTER 3 Performance Report Summary of Vote Performance Cumulative Progress Report for Projects and Programme Quarterly Progress Report for Projects and Programmes QUARTER 4: Workplans for Projects and Programmes Submission Checklist Page 1 Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports QUARTER 3: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution This section provides an overview of Vote expenditure (i) Snapshot of Vote Releases and Expenditures Table V1.1 below summarises cumulative releases and expenditures by the end of the quarter: Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases (i) Excluding Arrears, Taxes Budget by End by End End Mar Released Spent Spent Wage 11.218 9.015 9.015 8.648 80.4% 77.1% 95.9% Recurrent Non Wage 131.229 109.486 108.844 104.885 82.9% 79.9% 96.4% GoU 62.227 41.228 28.424 24.904 45.7% 40.0% 87.6% Development Ext Fin. 200.477 N/A 77.806 77.806 38.8% 38.8% 100.0% GoU Total 204.674 159.728 146.283 138.436 71.5% 67.6% 94.6% Total GoU+Ext Fin. (MTEF) 405.150 N/A 224.089 216.242 55.3% 53.4% 96.5% Arrears 0.642 N/A 0.642 0.553 100.0% 86.1% 86.1% (ii) Arrears and Taxes Taxes** 19.258 N/A 12.804 2.548 66.5% 13.2% 19.9% Total Budget 425.050 159.728 237.535 219.343 55.9% 51.6% 92.3% * Donor expenditure -

Mukono District Local Government

MUKONO DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT P.O.BOX 110, MUKONO BID NOTICE UNDER OPEN DOMESTIC BIDDING, PRE-QUALIFICATION AND FRAME WORK CONTRACTS FOR F/Y 2021/2022 Mukono District Local government invites detailed applications from rehabilitation materials interested and competent firms/ companies for pre-qualification and Muko542/Supls/21-22/013 Supply of inert and gravel pack frame work contract for provision of works, services and supplies for Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/014 Repair and servicing of the drilling rig F/Y 2021/2022 as described below. Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/015 Test pumping, casting, installation of boreholes and water quality sampling. CATEGORY A – PREQUALIFICATION FOR SERVICES Muko542/Supls/21-22/016 Supply of the rig and compressor spare ACTIVITY CODE ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION parts. Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0001 Property Valuation Muko542/Supls/21-22/017 Plumbing works and water supply Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0002 Motor vehicle and motorcycle insurance connections Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0003 Enforcement of revenue collection and Muko542/Supls/21-22/018 Supply of water quality reagents and management consumables Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0004 Garbage collection and management Muko542/Supls/21-22/019 Supply of medical equipment and Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0005 Car hire services reagents Muko542/Supls/21-22/020 Media and publication CATEGORY B – PREQUALIFICATION FOR WORKS Muko542/Supls/21-22/021 Supply of cleaning materials ACTIVITY CODE ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION Muko542/Wrks/21-22/0001 Construction and renovation of CATEGORY E- OPEN BIDDING buildings and civil works Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/00001 Property valuation of commercial building in Katosi TC, Ntenjeru Kisoga TC and Namataba TC CATEGORY C – PREQUALIFICATION FOR SUPPLIES ACTIVITY CODE ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION Bidding will be conducted in accordance with the Public Procurement Muko542/Supls/21-22/0001 Agricultural Equipment & Implements and disposal of Public Assets Act, 2003 of the Government of Uganda Muko542/Supls/21-22/0002 Entomological supplies and it’s open to all Bidders. -

Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:542 Mukono District for FY 2019/20. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Nkata. B. James Date: 05/12/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 2,165,188 541,297 25% Discretionary Government 4,425,042 1,190,092 27% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 35,247,076 9,611,327 27% Other Government Transfers 3,791,074 663,098 17% External Financing 256,500 42,410 17% Total Revenues shares 45,884,879 12,048,224 26% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 7,460,303 2,150,500 1,922,394 29% 26% 89% Finance 469,132 114,856 85,192 24% 18% 74% Statutory Bodies 1,007,284 252,999 177,696 25% 18% 70% Production and Marketing 2,330,532 595,709 469,467 26% 20% 79% Health 6,530,010 1,841,368 1,760,879 28% 27% 96% Education 24,190,088 6,039,281 5,341,989 -

Mukono Town Council

MUKONO TOWN COUNCIL Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Env ironmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Waste Composting Plant and Landfill in Katikolo Village, Mukono Town Council Prepared By: Enviro-Impact and Management Consults Total Deluxe House, 1ST Floor, Plot 29/33, Jinja Road Public Disclosure Authorized P.O. Box 70360 Kampala, Tel: 41-345964, 31-263096, Fax: 41-341543 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.enviro-impact.co.ug September 2006 Mukono Town Council PREPARERS OF THIS REPORT ENVIRO-IMPACT and MANAGEMENT CONSULTS was contracted by Mukono Town Council to undertake the Environmental impact Assessment study of the proposed Katikolo Waste Composting Plant and Landfill, and prepare this EIS on their behalf. Below is the description of the lead consultants who undertook the study. Aryagaruka Martin BSc, MSc (Natural Resource Management) Team Leader ………………….. Otim Moses BSc, MSc (Industrial Chemistry/Environmental Systems Analysis) …………………… Wilbroad Kukundakwe BSc Industrial Chemistry …………………… EIS Katikolo Waste Site i EIMCO Environmental Consultants Mukono Town Council TABLE OF CONTENTS PREPARERS OF THIS REPORT.....................................................................I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................... VI ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................. VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................VII -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

COVID-19 Effects on the Construction Industry

Issue No. 15, August 2020 THEME: COVID-19 & CONSTRUCTION SAFETY: Keep your site safe during COVID-19 crisis COVID-19: Govt’s intervention to aid sector ’s recovery is crucial RULES: Strict regulation key in eliminating shoddy work COVID-19 effects on the construction industry www.unabcec.co.ug UNABCEC UNABCEC_UG AUGUST, 2020 1 COVID-19 should The Contractor Magazine is a quarterly publication that acts as the voice for the leave you with AUTHENTIC ICON construction industry. We print and distribute The Contractor free of charge to UNABCEC many lessons members and all stakeholders in the construc- tion industry, international and local partners, am excited about this particular is- ministries, departments and agencies, works sue of The Contractor, you should and technical officers of all central and local I too, and this is why. Government entities, Members of Parliament, The lockdown was lifted and for banks, embassies, academic institutions and most sectors, work has resumed nor- the general public. We highlight issues and mally. Although operations of the con- possible solutions relating to the construction struction sector had not been halted as that usually happen at construction business community. Visit our website today to sites. Therefore, in addition to wear- access soft copies of the recent issues. part of measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic, operations were ing masks, do not downplay helmets, Call for articles made difficult by several restrictions, boots, reflectors and other safety gear. All articles on construction experiences, including movement of workers and More than this, insure your workers opinions on developing the industry, policy closure of material outlets. -

Vote: 542 Mukono District Structure of Budget Framework Paper

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2013/14 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Foreword The annual work plan and budget of the year 2013/14 has been out of deliberate efforts by the Technical and Political Leadership. The 2013/2014 Annual work plan and Budget provides a great opportunity for social economic advancement of the people of Mukono District. The planning and Budgeting process has taken a sizeable amount of time and financial resources. I therefore extend my appreciation to Government of Uganda and the private sector for their contribution to the making of this BFP. This plan is a strategic tool in the struggle to get the people of Mukono District out of absolute poverty. The investment areas covered aim at consolidating past achievements which address Primary Education, Primary Health Care, Modernization of Agriculture, etc. On average there has been increase in funding of key production sectors e.g. Agriculture and related activities together with empowering disadvantaged groups. The aim has been to capture pertinent issues that have direct bearing to household incomes. I would like to thank all Heads of Departments especially those who made presentations, the Lower Local Governments Councils, NGOs, delegates who participated in the district plan/ Budget conference and the district council for the roles they have played. In a special way I wish to thank the central Government for funding programmes and investments for 2012/2013. -

Biz Page 1.Indd

28 NEW VISION, Monday, May 9, 2016 BUSINESS SA FINANCES UNDER CONTROL — TREasURY South Africa’s treasury said on Saturday conclusion of the ratings review for a it was bringing public finances under possible downgrade of South Africa’s Africell, Airtel fight control, despite recent “adverse political Baa2 rating it launched in March. development” after Moody’s affirmed Nomura emerging markets analyst the country’s investment-grade credit Peter Attard Montalto, said in a brief rating, but kept its negative outlook. note, the move was a “marginal In a statement, the treasury said positive” but noted that Moody’s has President Jacob Zuma’s government been more upbeat on South Africa than over internet cables would “continue to demonstrate its other credit ratings agencies. commitment to translate plans into Standard & Poor’s, which is expected concrete actions that will ensure South to review South Africa in June, both rate By Edward Kayiwa cables in Kampala, in violation Africa remains an investment-grade the country BBB-, a notch lower than of a court injunction stopping country”. Moody’s announcement Moody’s and the lowest investment- A bitter row has erupted the Police search warrant. The late on Friday after domestic financial grade rating. between telecoms, Africell and injunction was granted by the markets had closed, marked the Reuters Airtel, over allegedly stolen fibre Magistrate’s Court at Nakawa, optic cables in several parts of Airtel stated. the country. Africell is accusing According to the statement Airtel of stealing its cables, signed by Airtel managing while Airtel pleads innocence, director, Tom Gutjahr, the saying it paid for the laying of its Uganda Communications infrastructure and is unaware of Commission (UCC) is aware what the contractor did. -

Assessment Form

Local Government Performance Assessment Mukono District (Vote Code: 542) Assessment Scores Crosscutting Minimum Conditions 78% Education Minimum Conditions 100% Health Minimum Conditions 90% Water & Environment Minimum Conditions 35% Micro-scale Irrigation Minimum Conditions 100% Crosscutting Performance Measures 63% Educational Performance Measures 57% Health Performance Measures 54% Water & Environment Performance Measures 75% Micro-scale Irrigation Performance Measures 25% 542 Crosscutting Performance Mukono Measures 2020 District Summary of No. Definition of compliance Compliance justification Score requirements Local Government Service Delivery Results 1 4 Service Delivery • Evidence that infrastructure There was evidence that the DDEG projects Outcomes of DDEG projects implemented using DDEG completed below were being used/functional by investments funding are functional and utilized the beneficiaries as per their profiles: as per the purpose of the project(s): Maximum 4 points on 1. Out Patient Department and latrine at this performance • If so: Score 4 or else 0 Nakifuma Health Centre III at a cost of Ugx 157 measure Million started in 18/19 and completed on 22/6/2020; 2. A two classroom block at Kayanja Coomunity Primary School in Nagojje Sub County at a cost of Ugx 144 Million started on 11/9/2019 and completed on 27/6/2020; and 3. Works on completed main administrative block at Ugx 40 Million started on 3/1/2020 and completed on 30/6/2020. 2 0 Service Delivery a. If the average score in the overall This Performance Measure was not applicable Performance LLG performance assessment until LLGs are assessed. increased from previous Maximum 6 points on assessment : this performance measure o by more than 10%: Score 3 o 5-10% increase: Score 2 o Below 5 % Score 0 2 3 Service Delivery b. -

Developmtnt (AFD)

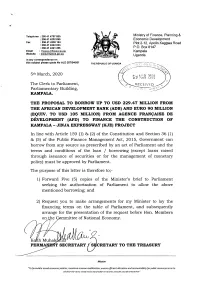

I ? Telephone :256 41 4707 0OO Ministry of Finance, Planning & :256 41 4232095 Economic Development Fax :256 41 4230 163 Plot2-12, Apollo Kaggwa Road :25641 4343O23 :256 41 4341 286 P.O. Box 8147 Email : financeifi)fi nanco.uo,ug Kampala Website : www.finance,go.uo Uganda ln any correspondence on this subject please quote No ALD 2071346101 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA '', a: ',-i -i i; l): I Stt' March, 2O2O 0 ll I'i,,:ifi ?l:?il The Clerk to Parliament, aECr:iv[:3 (l N .i'i r) '.. Parliamentary Building, 7 ':: ',,r i. tl.\l KAMPALA. THE PROPOSAL TO BORROW UP TO USD 229.47 MILLION FROM THE AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK (ADB} AND EURO 90 MILLION (EQUrV. TO USD 1O5 MILLIONI FROM AGENCE FRANgAISE DE DEVELoPMTNT (AFD) To TINANCE THE coNsrRUcrIoN oF r{AMPALA - JrNJA EXPRESSWAY (KJE) PROJECT In line with Article 159 (1) & (2) of the Constitution and Section 36 (1) & (5) of the Public Finance Management Act, 2015, Government can borrow from any source as prescribed by an act of Parliament and the terms and conditions of the loan / borrowing (except loans raised through issuance of securities or for the management of monetary policy) must be approved by Parliament. The purpose of this letter is therefore to;- 1) Forward Five (5) copies of the Minister's brief to Parliament seeking the authorization of Parliament to allow the above mentioned borrowing; and. 2) Request you to make arrangements for my Minister to lay the financing terms on the table of Parliament, and subsequently arrange for the presentation of the request before Hon. -

Stakeholder Engagement Plan

Kampala-Jinja Expressway PPP Project Phase 1 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Volume D: Stakeholder Engagement Plan prepared for Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) by Earth Systems and Atacama Consulting EARTH SYSTEMS Environment · Water · Sustainability August 2018 Rev2 Kampala-Jinja Expressway PPP Project Phase 1 Volume D: Stakeholder Engagement Plan DOCUMENT INFORMATION Project Title Kampala-Jinja Expressway PPP Project Phase 1 Document Title Volume D: Stakeholder Engagement Plan Document Name KJEXP1775_Ph1_SEP_Rev2 Document Version Rev1 Version Date August 2018 File name KJEXP1775_Ph1_SEP_Rev2 Project Manager Project Director Prepared for Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) Project ID KJEXP1775 DOCUMENT REVISION HISTORY Revision Issue Date Status Approved by Revision 0 May 2017 Rev0 Nigel Murphy Revision 1 May 2018 Rev1 Nigel Murphy Revision 2 August 2018 Rev2 Nigel Murphy DISTRIBUTION RECORD Copy Number Company / Position Name 1 Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) 2 Earth Systems 3 Atacama Consulting © Earth Systems Earth Systems This report is not to be used for purposes other than that for which it was intended. ABN 42 120 062 544 Environmental conditions change with time. The site conditions described in this report are 14 Church St based on observations made during the site visit and on subsequent monitoring results. Earth Hawthorn, Victoria 3122 Systems does not imply that the site conditions described in this report are representative of Australia past or future conditions. Where this report is to be made available, either in part or in its Tel: +61 (0)3 9810 7500 entirety, to a third party, Earth Systems reserves the right to review the information and Fax: +61 (0)3 9853 5030 documentation contained in the report and revisit and update ndings, conclusions and Web: www.earthsystems.com.au recommendations. -

Vote: 542 2014/15 Quarter 1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 542 Mukono District 2014/15 Quarter 1 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:542 Mukono District for FY 2014/15. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Chief Administrative Officer, Mukono District Date: 05/02/2015 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 542 Mukono District 2014/15 Quarter 1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % Receipts Budget UShs 000's Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 1,338,909 233,424 17% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 2,860,770 715,193 25% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 25,300,550 6,174,496 24% 2c. Other Government Transfers 2,759,364 1,256,460 46% 3. Local Development Grant 677,694 169,423 25% 4. Donor Funding 529,677 181,770 34% Total Revenues 33,466,963 8,730,765 26% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance Approved Budget Cumulative