A Law and Economics Policy Analysis of Sand Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Martinez.P65

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER PERSPECTIVES IN INDIAN DEVELOPMENT New Series 32 Social Metabolism and Environmental Conflicts in India Joan Martinez-Alier Leah Temper Federico Demaria ICTA, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Spain Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2014 NMML Occasional Paper © Joan Martinez-Alier, Leah Temper and Federico Demeria, 2014 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the opinion of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Society, in whole or part thereof. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail : [email protected] ISBN : 978-93-83650-34-7 Price Rs. 100/-; US $ 10 Page setting & Printed by : A.D. Print Studio, 1749 B/6, Govind Puri Extn. Kalkaji, New Delhi - 110019. E-mail : [email protected] NMML Occasional Paper Social Metabolism and Environmental Conflicts in India* Joan Martinez-Alier, Leah Temper and Federico Demaria Abstract This paper explains the methods for counting the energy and material flows in the economy, and gives the main results of the Material Flows for the economy of India between 1961 and 2008 as researched by Simron Singh et al. (2012). Drawing on work done in the Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabities and Trade (EJOLT) project, some illustrations are given of the links between the changing social metabolism and ecological distribution conflicts. These cover responses to bauxite mining in Odisha, conflicts on sand mining, disputes on waste management options in Delhi and ship dismantling in Alang, Gujarat. -

Understanding Precarity in the Context of the Political and Criminal Economy in India

Buried in Sand: Understanding Precarity in the Context of the Political and Criminal Economy in India Jordann Hass 6340612 Final Research Paper submitted to Dr. Melissa Marschke Final Version Abstract: As the world population grows and countries become more urbanized, the demand for sand is more prominent than ever. However, this seemingly infinite resource is being exhausted beyond its natural rate of renewal; we are running out of sand. The limited supply of sand has resulted in illicit sand trading globally, spawning gangs and mafias in a lethal black market. Through the nexus of politics, business and crime, India has demonstrated to be the most extreme manifestation of the global sand crisis. This paper will offer insight into the under-researched area of precarity surrounding the sand trade in the context of political criminality in India. By adopting an integrative approach to precarity, the analysis will review the direct and indirect impacts on livelihoods and local communities. The findings highlight how the collusive relations between the sand mafia and state authorities perpetuate a cycle of precarious labour and social-ecological conditions. To conclude, I will explore recommendations on how to address the implications of sand mining as a global community. 1.0 Introduction Sand is a fundamental component in modern society. Minuscule, and in some instances almost invisible, sand is one of the most important solid substances on earth (Beiser, 2018a). Historically, it was used as a form of verbal art that incorporated language, culture and expression through drawings. Eventually, the use of sand evolved into a material that was ‘malleable and durable, strong and fireproof,’ (Mars, 2019). -

The Unsustainable Use of Sand: Reporting on a Global Problem

sustainability Article The Unsustainable Use of Sand: Reporting on a Global Problem Walter Leal Filho 1,2,* , Julian Hunt 3, Alexandros Lingos 1, Johannes Platje 4 , Lara Werncke Vieira 5, Markus Will 6 and Marius Dan Gavriletea 7 1 European School of Sustainability Science and Research, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Ulmenliet 20, D-21033 Hamburg, Germany; [email protected] 2 Department of Natural Sciences, Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester Street, Manchester M1 5GD, UK 3 Energy Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Schlossplatz 1, A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria; [email protected] 4 WSB University in Wroclaw, ul. Fabryczna 29-31, 53-609 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] 5 Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul—UFRGS, Porto Alegre 90040-060, Brazil; [email protected] 6 Zittau/Görlitz University of Applied Sciences, Theodor-Körner-Allee 16, D-02763 Zittau, Germany; [email protected] 7 Business Faculty, Babe¸s-BolyaiUniversity, Horea 7, 400038 Cluj–Napoca, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Sand is considered one of the most consumed natural resource, being essential to many industries, including building construction, electronics, plastics, and water filtration. This paper assesses the environmental impact of sand extraction and the problems associated with its illegal exploitation. The analysis indicates that extracting sand at a greater rate than that at which it is naturally replenished has adverse consequences for fauna and flora. Further, illicit mining activities compound environmental damages and result in conflict, the loss of taxes/royalties, illegal work, and Citation: Leal Filho, W.; Hunt, J.; losses in the tourism industry. -

MARCH CURRENT AFFAIR NATIONAL AFFAIRS Shah, Minister of State (Mos) for Home Affairs - G

1 MARCH CURRENT AFFAIR NATIONAL AFFAIRS Shah, Minister of State (Mos) for Home Affairs - G. Kishan Reddy & Nityanand Rai. 1. Name the Campaign which was launched by Lok Sabha speaker Om Birla in Kota, 3. ‘Chowk’ the Historic city of Jammu & Rajasthan to provide nutritional support Kashmir(J&K) has been renamed as to pregnant women and adolescent girls ‘Bharat mata chowk’. Who is the present (Feb 2020). governor of J&K? 1) Poshan Abhiyan 1) Radha Krishna Mathur 2) Eat right movement 2) Droupadi Murmu 3) Poshan Maa 3) Jagdish Mukhi 4) Suposhit Maa Abhiyan 4) Girish Chandra Murmu 5) Fit India 5) Biswa Bhusan Harichandan 1. Answer – 4) Suposhit Maa Abhiyan 3. Answer – 4) Girish Chandra Murmu Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla has launched The Jammu & Kashmir’s historic City Chowk, ‘Suposhit Maa Abhiyan’ in his constituency Kota, which was a commercial center in Old Jammu, has Rajasthan, to provide nutritional support to been renamed as ‘Bharat Mata Chowk’. The Capital pregnant women and adolescent girls. Smriti Irani, of the J&K - Srinagar (May–October) Jammu Ministry of Women & Child Development & (Nov–April) & Governor - Girish Chandra Murmu Ministry of Textiles, also presided over the function. 4. Name the Indian state which prohibits the About Suposhit Maa Abhiyan: In the first phase online supply of food from Food Business of the campaign, 1,000 kits of 17 kg balanced diet Operators (FBOs) who don’t possess each was provided to 1,000 pregnant women. hygiene rating. 2. Union Home ministry has appointed S N 1) Punjab Shrivastava as additional charge of Delhi 2) Haryana Police Commissioner (Feb 2020). -

Life Cycle Assessment of Zircon Sand

The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01619-5 LCI METHODOLOGY AND DATABASES Life cycle assessment of zircon sand Johannes Gediga1 & Andrea Morfino1 & Matthias Finkbeiner2 & Matthias Schulz3 & Keven Harlow4 Received: 24 June 2018 /Accepted: 27 March 2019 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Purpose To support the needs of downstream users of zircon sand and other industry stakeholders, the Zircon Industry Association (ZIA) conducted an industry-wide life cycle assessment (LCA) with the aim to quantify the potential environmental impacts of zircon sand production, from mining to the separation of zircon sand (zirconium silicate or ZrSiO4). This novel work presents the first, globally representative LCA dataset using primary data from industry. The study conforms to relevant ISO standards and is backed up by an independent critical review. Methods Data from ZIA member companies representing 10 sites for the reference year 2015 were collected. In total, more than 77% of global zircon sand production was covered in this study. All relevant mining routes (i.e. wet and dry mining) were considered in the investigation, as well as all major concentration and separation plants in major zircon sand–producing regions of the world (i.e. Australia, South Africa, Kenya, Senegal and the USA). As it is common practise in the metal and mining industry, mass allocations were applied with regard to by-products (Santero and Hendry, Int J Life Cycle Assess 21:1543–1553, Santero and Hendry 2016) where economic allocation is only applied if high-valued metals like PGMs are separated with a process flow. -

Karen Ensall Page 3 El Monte Sand Mine & Nature Preserve

Karen Ensall Page 3 El Monte Sand Mine & Nature Preserve PDS2015-MUP-98-014W2, PDS2015-RP-15-001 Policies and Recommendations page 8 5. Provide for street tree planting and landscaping, as well as the preservation of indigenous plant life. 7. Bufferresidential areas from incompatible activitiesthat create heavy traffic,noise, lighting, odors, dust, and unsightly views. (Pp) 9. Require strict and literal interpretation of the requirements for a Major Use Permit when analyzing such permit applications. {Pp) 10. Allow certain non-disruptive commercial uses in residential areas after analysis on a site-specific basis. (Pp) I do not believe this project is non-disruptive! Please address. Policies and Recommendations page 11 4. Encourage commercial activities that would not interfere either functionally or visually with adjacent land uses or the rural atmosphere of the community. (P) 15. Require commercial and industrial land uses to minimize adverse impacts, such as noise, light, traffic congestion, odors, dust, etc. AGRICULTURAL GOAL page 12 PROVIDE FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AGRICULTURAL LAND USES, WHILE MAINTAINING THEIR COMPATIBILITYWITH OTHER NON-RURAL USES. FINDINGS Lakeside has a unique agricultural heritage, which the community wishes to perpetuate. In the urban core, large scale agricultural uses have given way to residential development. In spite of this, extensive portions of the Plan Area display significant primary and secondary agricultural uses. These areas include Eucalyptus Hills, Moreno Valley, the El Monte Road area, and Blossom Valley. Secondary agricultural uses are also common in areas within the Village Boundary Line Maintaining and enhancing these agricultural uses is essential to the basic character of the Lakeside community. -

Crystalline Silica in Air & Water, and Health Effects

Crystalline Silica IN AIR & WATER, AND HEALTH EFFECTS Crystalline silica is a type of silica formed from silica sand, a ‘building block’ material in rock, soil and sand, through natural heat and pressure. It is used in a number of industrial and commercial processes like glass-making, road-building, hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas production, water filtration, and even electronics. Who Does It Affect? Silica Sand Mining & Water Exposure to silica sand particles is of Silica sand mining or processing can affect greatest concern for workers in the fracking drinking water sources. or mining industry, and other construction trades where dust is generated. People who Groundwater live in communities near silica mining and processing operations have not been shown Any mine may create a pathway for to be exposed to levels of crystalline silica chemicals and/or bacteria to more easily harmful for health. reach the groundwater. The risks to drinking water depend on: ▪ How close the mining operations are to Silica in Air the groundwater’s surface Crystalline silica can be released into the air ▪ The use of heavy equipment from cutting, grinding, drilling, crushing, ▪ Leaks and spills of fuel, engine oil or sanding, or breaking apart many different other chemicals materials. A few years ago, concern ▪ Runoff from contaminant sources or mounted surrounding silica sand mining waste dumped illegally in the mine activities and the potential release of large Products called flocculants used by some amounts of crystalline silica into the air. In frac sand mines (mines that extract silica response, MDH developed a health-based sand to be used for hydraulic fracturing) guidance value for crystalline silica in the air may contain low concentrations of and the Minnesota Pollution Control chemicals (acrylamide and DADMAC) that Agency (MPCA) began monitoring for are of potential concern. -

264 Comm-Report-2015 Science & Technology.Pmd

REPORT NO. 264 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS TWO HUNDRED SIXTY FOURTH REPORT Environmental Issues in Mumbai and Visakhapatnam (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on the 21st July, 2015) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on the 22nd July, 2015) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi July, 2015/Ashadha, 1937 (Saka) Hindi version of this publication is also available PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS TWO HUNDRED SIXTY FOURTH REPORT Environmental Issues in Mumbai and Vishakhapatanam (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 21st July, 2015) (Laid on the Table of the Lok Sabha on 22nd July, 2015) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi July, 2015/Ashadha, 1937 (Saka) Website: http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] C O N T E N T S PAGES 1. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE .......................................................... (i) 2. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ (iii) 3. ACRONYMS ....................................................................................... (v) 4. REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ...................................................................... 1–13 5. RECOMMENDATIONS/OBSERVATIONS – AT A GLANCE.......................................... 14–16 6. MINUTES ................................................................................................ 17–22 7. -

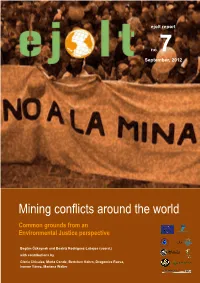

Mining Conflicts Around the World - September 2012

Mining conflicts around the world - September 2012 ejolt report no. 7 September, 2012 Mining conflicts around the world Common grounds from an Environmental Justice perspective Begüm Özkaynak and Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos (coord.) with contributions by Gloria Chicaiza, Marta Conde, Bertchen Kohrs, Dragomira Raeva, Ivonne Yánez, Mariana Walter EJOLT Report No. 07 Mining conflicts around the world - September 2012 September - 2012 EJOLT Report No.: 07 Report coordinated by: Begüm Özkaynak (BU), Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos (UAB) with chapter contributions by: Gloria Chicaiza (Acción Ecológica), Marta Conde (UAB), Mining Bertchen Kohrs (Earth Life Namibia), Dragomira Raeva (Za Zemiata), Ivonne Yánez (Acción Ecologica), Mariana Walter (UAB) and factsheets by: conflicts Murat Arsel (ISS), Duygu Avcı (ISS), María Helena Carbonell (OCMAL), Bruno Chareyron (CRIIRAD), Federico Demaria (UAB), Renan Finamore (FIOCRUZ), Venni V. Krishna (JNU), Mirinchonme Mahongnao (JNU), Akoijam Amitkumar Singh (JNU), Todor Slavov (ZZ), around Tomislav Tkalec (FOCUS), Lidija Živčič (FOCUS) Design: Jacques bureau for graphic design, NL Layout: the world Cem İskender Aydın Series editor: Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos The contents of this report may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational or non-profit services without special Common grounds permission from the authors, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. This publication was developed as a part of the project from an Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade (EJOLT) (FP7-Science in Society-2010-1). EJOLT aims to improve policy responses to and support collaborative research and action on environmental Environmental conflicts through capacity building of environmental justice groups around the world. Visit our free resource library and database at Justice perspective www.ejolt.org or follow tweets (@EnvJustice) to stay current on latest news and events. -

Sand Mafias in India – Disorganized Crime in a Growing Economy Introduction

SAND MAFIAS IN INDIA Disorganized crime in a growing economy Prem Mahadevan July 2019 SAND MAFIAS IN INDIA Disorganized crime in a growing economy Prem Mahadevan July 2019 Cover photo: Adobe Stock – Alex Green. © 2019 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 What are the ‘sand mafias’? ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Sand: A diminishing resource .................................................................................................................................. 7 How the illicit trade in sand operates ............................................................................................................ 9 Political complicity in India’s illicit sand industry ....................................................................................11 Dividing communities from within .................................................................................................................13 -

Focus on Guyana Budget 2021 Contents Caveat

Focus on Guyana Budget 2021 Contents Caveat Budget arithmetic .......................................... 3 Focus on Guyana Budget 2021 is based on the presentation delivered by Dr. Ashni Singh, Macroeconomic indicators .............................. 4 Senior Minister in the Office of the President with responsibility for Finance in Parliament on 12 Tax measures ................................................. 5 February 2021. This publication was prepared by Ernst & Young EY Consulting ................................................ 8 Services Inc. The contents are intended as a general guide for the benefit of our clients and associates and Digital Utopia — Guyana 2030 ......................... 9 are for information purposes only. It is not intended to be relied upon for specific Tax rates for income year 2021 .................... 11 tax and/or business advice and as such, users are encouraged to consult with professional advisors on Status of fiscal measures 2020 ..................... 13 specific matters prior to making any decision. This publication is distributed with the understanding Tax dispute resolution process ...................... 15 that Ernst & Young Services Inc. or any other member of the Global Ernst & Young organisation is About EY Caribbean ..................................... 17 not responsible for the result of any actions taken on the basis of this publication, nor for any omissions or Tax services and contacts ............................. 18 errors contained herein. Ernst & Young Services Inc. The Pegasus Hotel, -

Placement Brochure

PLACEMENT BROCHURE 2018 -20 M.A/M.Sc In disaster management Jamsetji Tata School of Disaster Studies Tata Institute of social sciences,Mumbai CONTENTS 01 Message From the Director 02 Message From the Dean 11 Voices From Field 03 Message From the Coordinator 12 TISS Interventions 04 About JTSDS 13 Response To Disasters - Kerala Flood 06 Why US? 14 Faculty Profile 07 Courses Highlights 15 Batch Diversity 08 Distribution Of Credit Hours 16 Alumni Network 09 Subjects Offered 17 Student Profiles 35 Alumni Testimonials 37 Flagship Events 38 Some Glimpses From Field 39 Contact Details The Tata Institute of Social Sciences, now in its 84th year, continues to impact social policies, programmes and ground-level action for the betterment of Message society. As a community-engaged University with campuses in Mumbai, Tuljapur, Guwahati and Hyderabad, the Institute's vision is to create socially relevant knowledge and transfer that knowledge through its various teaching From the programmes and field action projects. With over eight decades of experi- ence, the Institute creates highly knowledgeable and skilled human service professionals and empowers them to find sustainable solutions to people's Director problems, social issues and social transformation. The Institute has been involved in addressing disasters since the partition of 1947. Student and faculty interventions have continued through the decades whether it be the Bhopal gas tragedy, Latur earthquake, the Tsunami, the Assam riots, or the Uttarakhand floods. The Jamsetji Tata School of Disasters Studies demonstrates our commitment towards developing a scientific approach to understanding and responding to disasters and their impacts. Our Masters' programme in Disaster Management is the first of its kind in the country.