Development and Validation of an Algorithm to Identify Endometrial Adenocarcinoma in US Administrative Claims Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 – the Following CPT Codes Are Approved for Billing Through Women’S Way

WHAT’S COVERED – 2021 Women’s Way CPT Code Medicare Part B Rate List Effective January 1, 2021 For questions, call the Women’s Way State Office 800-280-5512 or 701-328-2389 • CPT codes that are specifically not covered are 77061, 77062 and 87623 • Reimbursement for treatment services is not allowed. (See note on page 8). • CPT code 99201 has been removed from What’s Covered List • New CPT codes are in bold font. 2021 – The following CPT codes are approved for billing through Women’s Way. Description of Services CPT $ Rate Office Visits New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; straightforward decision making; 15-29 minutes 99202 72.19 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; low level decision making; 30-44 minutes 99203 110.77 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; moderate level decision making; 45-59 minutes 99204 165.36 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; high level decision making; 60-74 minutes. 99205 218.21 Established patient; evaluation and management, may not require presence of physician; 99211 22.83 presenting problems are minimal Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, straightforward decision making; 10-19 99212 55.88 minutes Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, low level decision making; 20-29 minutes 99213 90.48 Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, moderate level decision making; 30-39 99214 128.42 minutes Established patient; comprehensive history exam, high complex decision making; 40-54 minutes 99215 128.42 Initial comprehensive -

Endometrial Biopsy | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Endometrial Biopsy This information describes what to expect during and after your endometrial biopsy. About Your Endometrial Biopsy During your endometrial biopsy, your doctor will remove a small piece of tissue from the lining of your uterus. The lining of your uterus is called your endometrium. This tissue is sent to the pathology department to be examined under a microscope. The pathologist will look for abnormal cells or signs of cancer. Before Your Procedure Tell your doctor or nurse if: You’re allergic to iodine. You’re allergic to latex. There’s a chance that you’re pregnant. If you still get your period and are between ages 11 and 50, you will need to take a urine pregnancy test to make sure you’re not pregnant. You won’t need to do anything to get ready for this procedure. During Your Procedure You will have your endometrial biopsy done in an exam room. You will lie on your back as you would for a routine pelvic exam. You will be awake during the procedure. Endometrial Biopsy 1/3 First, your doctor will put a speculum into your vagina. A speculum is a tool that will gently spread apart your vaginal walls, so your doctor can see your cervix (the bottom part of your uterus). Next, your doctor will clean your cervix with a cool, brown solution of povidone- iodine (Betadine® ). Then, they will put a thin, flexible tool, called a pipelle, through your cervix and into your uterus to take a small amount of tissue from your endometrium. -

The Role of Hysteroscopy in Diagnosing Endometrial Cancer

The role of hysteroscopy in diagnosing endometrial cancer Certain hysteroscopic findings correlate with the likelihood of endometrial carcinoma—and the absence of pathology. Here is a breakdown of hysteroscopic morphologic findings and hysteroscopic-directed biopsy techniques. Amy L. Garcia, MD or more than 45 years, gynecologists He demonstrated the advantages of using have used hysteroscopy to diagnose hysteroscopy and directed biopsy in the eval- F endometrial carcinoma and to asso- uation of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to ciate morphologic descriptive terms with obtain a more accurate diagnosis compared visual findings.1 Today, considerably more with dilation and curettage (D&C) alone clinical evidence supports visual pattern rec- (sensitivity, 98% vs 65%, respectively).2 ognition to assess the risk for and presence of Also derived from this work is the clini- IN THIS endometrial carcinoma, improving observer- cal application of the “negative hysteroscopic ARTICLE dependent biopsy of the most suspect lesions view” (NHV). Loffer used the following cri- (VIDEO 1). teria to define the NHV: good visualization Hysteroscopic In this article, I discuss the clinical evo- of the entire uterine cavity, no structural classification lution of hysteroscopic pattern recognition abnormalities of the cavity, and a uniformly of endometrial Ca of endometrial disease and review the visual thin, homogeneous-appearing endometrium findings that correlate with the likelihood of without variations in thickness (TABLE 1). The this page endometrial carcinoma. In addition, I have last criterion can be expected to occur only in provided 9 short videos that show hystero- the early proliferative phase or in postmeno- Negative scopic views of various endometrial patholo- pausal women. -

STOP Performing Dilation and Curettage for the Evaluation Of

STOP/START Diagnostic hysteroscopy spies polyp previously missed on transvaginal ultrasound and dilation and curettage. STOP performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding START performing in-office hysteroscopy to identify the etiology of abnormal uterine bleeding }expert commentary her treatment she had a 3-year history of Amy Garcia mD, Director, Center for abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from con- Women’s Surgery and Garcia Institute for management secutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the Hysteroscopic Training, Albuquerque, and Clinical Assistant Professor, Department patient had progressively thickening endome- obg r of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University trium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office O r f of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albu- E biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. f querque. Dr. Garcia serves on the OBG ie An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was K ManageMent Board of Editors. On the Web aig Dr. Garcia reports receiving grant support from Hologic; CASe In-office hysteroscopy spies being a consultant to Conceptus, Boston Scientific, Ethicon : Cr 12 intraoperative Endosurgery, IOGYN, Minerva, Hologic, Smith & Nephew, previously missed polyp ation videos from and Karl Storz Endoscopy; and being a member of the r A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast Dr. Garcia, at speakers’ bureau for Conceptus, Karl Storz Endoscopy, and ust ll obgmanagement.com cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During Ethicon Endosurgery. I 44 OBG Management | June 2013 | Vol. 25 No. 6 obgmanagement.com performed with negative histologic diagnosis. FIGURE consecutive ultrasounds evaluating The patient is seen in consultation, and abnormal bleeding the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE). -

The Woman with Postmenopausal Bleeding

THEME Gynaecological malignancies The woman with postmenopausal bleeding Alison H Brand MD, FRCS(C), FRANZCOG, CGO, BACKGROUND is a certified gynaecological Postmenopausal bleeding is a common complaint from women seen in general practice. oncologist, Westmead Hospital, New South Wales. OBJECTIVE [email protected]. This article outlines a general approach to such patients and discusses the diagnostic possibilities and their edu.au management. DISCUSSION The most common cause of postmenopausal bleeding is atrophic vaginitis or endometritis. However, as 10% of women with postmenopausal bleeding will be found to have endometrial cancer, all patients must be properly assessed to rule out the diagnosis of malignancy. Most women with endometrial cancer will be diagnosed with early stage disease when the prognosis is excellent as postmenopausal bleeding is an early warning sign that leads women to seek medical advice. Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is defined as bleeding • cancer of the uterus, cervix, or vagina (Table 1). that occurs after 1 year of amenorrhea in a woman Endometrial or vaginal atrophy is the most common cause who is not receiving hormone therapy (HT). Women of PMB but more sinister causes of the bleeding such on continuous progesterone and oestrogen hormone as carcinoma must first be ruled out. Patients at risk for therapy can expect to have irregular vaginal bleeding, endometrial cancer are those who are obese, diabetic and/ especially for the first 6 months. This bleeding should or hypertensive, nulliparous, on exogenous oestrogens cease after 1 year. Women on oestrogen and cyclical (including tamoxifen) or those who experience late progesterone should have a regular withdrawal bleeding menopause1 (Table 2). -

Comparison of Hysterosalpingography and Hysteroscopy in Evaluating the Uterine Cavity in Infertile Women

MOJ Women’s Health Research Article Open Access Comparison of hysterosalpingography and hysteroscopy in evaluating the uterine cavity in infertile women Abstract Volume 8 Issue 1 - 2019 Background: Infertility in women is predominantly associated with uterine cavity Baydaa F Alsannan,1 Ghadeer S Akbar,2 abnormalities. Uterine cavity anomalies and damage to the fallopian tubes may occur 3 due to various reasons such as endometriosis, polyps, adhesions and scar tissues. Anthony P Cheung 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Objective: To investigate the diagnostic value of hysterosalpingography (HSG) in Kuwait, Kuwait comparison to hysteroscopy (HSC) for various structural and intracavitary uterine 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ministry of Health, pathologies in women with infertility. Kuwait 3Department of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Materials and methods: An observational study of 280 women with infertility was University of British Colombia, Canada carried out to compare the diagnostic values of HSG and HSC in the diagnosis of uterine pathologies in women enduring infertility. The specific uterine conditions Correspondence: Baydaa Al Sannan, Department of evaluated were intrauterine synechiae, intrauterine fibroids/polyps and Mullerian Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of medicine, Kuwait congenital anomalies. The main outcome measures were sensitivity, specificity, University, Kuwait, Tel +965 25319601, positive and negative predictive values of HSG relative to hysteroscopy in diagnosing Email the following uterine pathologies: intrauterine synechiae, intrauterine fibroids/polyps Received: December 18, 2018 | Published: January 16, 2019 and Mullerian anomalies. Results: HSG had a sensitivity of 75% in detecting intrauterine synechiae, specificity of 86.5%, positive predictive value of 63% and negative predictive value of 91.8%. -

Cervical Dysplasia, Colposcopy and Biopsy

University of California, Berkeley 2222 Bancroft Way Berkeley, CA 94720 Appointments 510/642-2000 Online Appointment www.uhs.berkeley.edu Cervical Dysplasia, Colposcopy and Biopsy Dysplasia Dysplasia is a term used when normal cell characteristics such as the nucleus and cell size are altered or distorted. Cervical dysplasia is most often related to infection by the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV). HPV inserts itself into the nucleus of cervical cells; this alters normal cell development. HPV infection most often occurs during sexual contact. Cervical dysplasia represents an abnormality which can potentially progress into cervical cancer if not appropriately monitored and treated. It may also be transient (as with mild dysplasia) and is most often treatable (as with moderate or severe dysplasia). Colposcopy Colposcopy is a method of viewing the vulva, perineum, vagina and cervix, using magnification. Colposcopy is most often used as an adjunct to a Pap test, as both play an important role in identifying and monitoring suspicious or abnormal vaginal and/or cervical changes. The Pap identifies that a problem exists and the colposcopy identifies the specific site of the problem. Vulvar colposcopy may be used to evaluate unusual changes or irritations of the vulva which may be associated with dysplasia, cancer, eczema, estrogen deficiency, etc. If you have been advised to have a colposcopy you can expect that it will be very similar to obtaining a routine Pap test. What will be different? 1) Vinegar will be applied with a Q-tip; abnormal areas are highlighted as the vinegar is absorbed. Often the vinegar causes a mild stinging or mild cramping sensation when applied to the cervix. -

Colposcopy, Treatment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Endometrial Assessment BARBARA S

Gynecologic Procedures: Colposcopy, Treatment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Endometrial Assessment BARBARA S. APGAR, MD; AMANDA J. KAUFMAN, MD; CATHERINE BETTCHER, MD; and EBONY PARKER-FEATHERSTONE, MD, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan Women who have abnormal Papanicolaou test results may undergo colposcopy to determine the biopsy site for his- tologic evaluation. Traditional grading systems do not accurately assess lesion severity because colposcopic impres- sion alone is unreliable for diagnosis. The likelihood of finding cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or higher increases when two or more cervical biopsies are performed. Excisional and ablative methods have similar treatment outcomes for the eradication of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. However, diagnostic excisional methods, including loop electrosurgical excision procedure and cold knife conization, are associated with an increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, such as preterm labor and low birth weight. Methods of endometrial assessment have a high sen- sitivity for detecting endometrial carcinoma and benign causes of uterine bleeding without unnecessary procedures. Endometrial biopsy can reliably detect carcinoma involving a large portion of the endometrium, but is suboptimal for diagnosing focal lesions. A 3- to 4-mm cutoff for endometrial thickness on transvaginal ultrasonography yields the highest sensitivity to exclude endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women. Saline infusion sonohysteros- copy can differentiate -

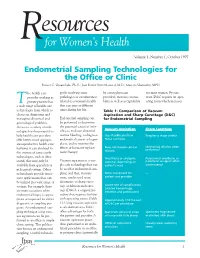

Endometrial Sampling Technologies for the Office Or Clinic Forrest C

esources Rfor Women’s Health Volume 1, Number 1, October 1997 Endometrial Sampling Technologies for the Office or Clinic Forrest C. Greenslade, Ph.D.; José David Ortiz Mariscal, M.D.; Marian Abernathy, MPH he health care gy for resolving some by a non-physician for most women. By con- provider working in pathologies or circumstances provider), increases accessi- trast, D&C requires an oper- T private practice has related to a woman’s health bility as well as acceptability ating room which increases a wide range of health care that can arise at different technologies from which to times during her life. Table 1: Comparison of Vacuum choose in diagnosing and Aspiration and Sharp Curettage (D&C) managing obstetrical and Endometrial sampling can for Endometrial Sampling gynecological problems. be performed to determine Access to a variety of tech- the potential causes of infer- Vacuum Aspiration Sharp Curettage nologies has the potential to tility, to evaluate abnormal help health care providers uterine bleeding, to diagnose Uses flexible plastic or Requires a sharp curette offer better, more appropri- endometrial cancer or hyper- metal cannulae ate reproductive health care; plasia, and to monitor the effects of hormone replace- Does not require cervical Mechanical dilation often however, it can also lead to performed the overuse of some costly ment therapy. dilation technologies, such as ultra- Anesthesia or analgesia Paracervical anesthesia or sound, that may only be Vacuum aspiration is a sim- optional, depending on parenteral analgesic often available from specialists or ple, safe technology that can patient’s need administered in hospital settings. Other be used for endometrial sam- technologies provide innov- pling, and that, in many More convenient for — ative applications that can cases, can be used as an patient and provider be utilized in a wide range of alternative to sharp curet- settings. -

Vtgyn Endo Biopsy 1.11

Endometrial Biopsy Before having an endometrial biopsy, you need to know the alternatives, possible benefits, risks, and warning signs. We have listed them here for you. We are happy to answer any questions you have. What is endometrial biopsy? Endometrial biopsy is a way to obtain a small sample of the lining of the uterus — the endometrium. How is endometrial biopsy done? The woman lies in the same position used for a Pap test. A speculum is inserted into the vagina. The clinician gently inserts a thin biopsy instrument through the cervix into the uterus. It is sometimes necessary to put a grasping instrument on the cervix or use thin metal dilators to open the cervix. A sample of tissue is taken. The sample is sent to a laboratory to be examined under the microscope by a doctor. The findings are sent to Vermont Gynecology. What will the endometrial biopsy feel like? Some women feel discomfort when the speculum is inserted into the vagina — like having a Pap test. Most women will feel brief cramping during the biopsy. It may be mild or severe. Sometimes women feel dizzy or faint. You will be offered pain medication to help with cramping from the biopsy. There may be slight spotting or light bleeding after the endometrial biopsy. Reasons for endometrial biopsy Endometrial biopsy may be recommended for several reasons. It can evaluate abnormal bleeding from the uterus. It can detect abnormal or pre-cancerous cells in the uterus. It can determine if ovulation has occurred. Benefits Endometrial biopsy is a safe procedure. -

After Having an Endometrial Biopsy And/Or a Hysteroscopy

Page 1 of 2 Patient After having an endometrial biopsy Information and/or a hysteroscopy Introduction You have had an endometrial biopsy and/or a hysteroscopy performed. The results of the hysteroscopy have been discussed with you today. This leaflet will give you information about what to expect after having a hysteroscopy and when to expect the results from an endometrial biopsy. Results If you have had a biopsy (tiny piece of tissue) taken from the lining of your uterus (womb) called the endometrium or a polyp removed, then we will write to you with the results when it has been examined in the laboratory. We usually receive the results within 5 weeks. As well as the results of the biopsy the letter will inform you if a follow up appointment is needed. Your GP will also receive a copy of the results. Risks and side effects As part of the hysteroscopy, a water solution was used to allow us to see the uterine cavity (inside the womb). It is normal that you may have a watery, blood stained discharge for the next 24 hours followed by light bleeding for up to a week. However, if the bleeding does not settle after 2 weeks or you pass lots of blood clots, then we advise you to see your GP. Due to the risk of infection it is recommended that you use sanitary towels and not tampons while you are bleeding. Once the bleeding has stopped you can resume sexual Reference No. intercourse when you feel ready. GHPI0782_12_19 Department Gynaecology Review due December 2022 www.gloshospitals.nhs.uk Page 2 of 2 Patient Will I have any pain? Information If you do experience any discomfort following the biopsy and hysteroscopy, simple pain relief such as paracetamol should help. -

Assessment of Endometrial Cavity of Infertil Patients with Transvaginal Sonography, Hysterosalpingography, and Hysterescopy

Eastern Journal of Medicine 17 (2012) 67-71 Original Article Assessment of endometrial cavity of infertil patients with transvaginal sonography, hysterosalpingography, and hysterescopy Banu Bingola,*, Faruk Abikeb, Herman Iscia aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Istanbul Bilim University, Istanbul, Turkey bDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medicana International Ankara Hospital, Ankara, Turkey Abstract. To compare the accuracy of transvaginal sonography (TVS), hysterosalpingography (HSG) and hysteroscopy (HS) for uterine pathologies among infertile women. 168 women with diagnosis of infertility were enrolled in this study and assessed with TVS, HSG and HS. TVS, HSG and HS were carried out in all cases, in the 5th-8th days of follicular phase of the cycle. Operative hysteroscopy with directed biopsy was considered as the gold standard. HSG, TVS, and HS were conducted by specialized gynecologists, who were blinded to the results of the other examinations. Endometrial polyp (n=66, 39%), submucous myoma (n=46, 28%), endometrial hyperplasia (n=29, 17%) and suspect of intrauterine synechia (n=27, 16%) were detected with TVS. In the evaluation with HSG results, submucous myoma or polyp (n=42, 25%), irregular uterine contour (n=29, 17%), intrauterine synechia (n=24, 15%) were detected. 73 patients (43%) had normal HSG results. HS (with or without resection) results detected endometrial polyp (n=59, 35%), submucous myoma (n=47, 28%), endometrial hyperplasia (n=35, 21%) and intrauterine synechia (n=27, 16%). Endometrial biopsy revealed no atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium. TVS is the primary investigative method for evaluating every infertile couple by means of uterine cavity and ovaries. TVS seems to be additional and superior to HSG.