The Detectives in Agatha Christie's Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Detectives in Modern Detective Novels an Analysis Of

Female Detectives in Modern Detective Novels An Analysis of Miss Marple and V. I. Warshawski Writer: Sladana Marinkovic Supervisor: Dr Michal Anne Moskow Examination assignment 10 p, English 41-60 p 10 p Essay Department of Education and Humanities 03-02-04 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Page 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………….….………………………....3 1.1 Background……………………………………………..……………………...…4 1.2 Summary of the Novels…………………………….…………………..…5 1.3 Literature Review……..…………………………………….….……………..7 1.4 Research Questions……………………………………………………….….9 1.5 Methods…………………………………….…………………………………….…9 2. LITERATURE AND CULTURE…………………………………………..10 2.1. The Women Detectives…...……….………………………..……………11 2.2. Working Conditions……………………….…………………….………....16 2.3. The Murderers and the Victims………………………………….….17 3. LANGUAGE AND CULTURE………………………...…………………...18 3.1. Gender and Language…………….……………………….……………….20 3.2. Swearing and Taboo……………………………………………..………….22 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………...24 5. BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………...…26 2 1. INTRODUCTION Ever since Edgar Allan Poe wrote what is today considered to be the very first detective short story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”(1841), detective novels have fascinated a lot of people. At first the authors entertained their audience by writing exciting stories where male detectives and spies played the lead part (Berger, 1992, 81). But since then, the murder mystery has evolved and been modified many times. For example, the appearance of the female detectives first emerges in Victorian literature. In this essay I will discuss two fictive women detectives, Christie’s Miss Marple and Paretsky’s V. I. Warshawski. These two detectives, and writers, belong to different times and cultures, but as readers, we must ask ourselves some basic questions before we start to compare them. Some of these questions I will consider later in section 1.4. -

Agatha Christie - Third Girl

Agatha Christie - Third Girl CHAPTER ONE HERCULE POIROT was sitting at the breakfast table. At his right hand was a steaming cup of chocolate. He had always had a sweet tooth. To accompany the chocolate was a brioche. It went agreeably with chocolate. He nodded his approval. This was from the fourth shop he had tried. It was a Danish patisserie but infinitely superior to the so-called French one near by. That had been nothing less than a fraud. He was satisfied gastronomically. His stomach was at peace. His mind also was at peace, perhaps somewhat too much so. He had finished his Magnum Opus, an analysis of great writers of detective fiction. He had dared to speak scathingly of Edgar Alien Poe, he had complained of the lack of method or order in the romantic outpourings of Wilkie Collins, had lauded to the skies two American authors who were practically unknown, and had in various other ways given honour where honour was due and sternly withheld it where he considered it was not. He had seen the volume through the press, had looked upon the results and, apart from a really incredible number of printer's errors, pronounced that it was good. He had enjoyed this literary achievement and enjoyed the vast amount of reading he had had to do, had enjoyed snorting with disgust as he flung a book across the floor (though always remembering to rise, pick it up and dispose of it tidily in the waste-paper basket) and had enjoyed appreciatively nodding his head on the rare occasions when such approval was justified. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background of The Study Agatha Christie is a British author in the 20th century who is famous for her novels. She is also famous for her plays, such as The Mousetrap, and short stories, such as The Submarine Plans and The Second Gong. She is considered to be one of the most famous murder mystery writers. She is clever at making stories and unforgettable detective characters. Agatha Christie has made a great contribution to the world of literature, especially in the genre of detective story. Most of her works have been filmed and the stories of her two famous detective characters, Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot, have been made into a serial in television and radio versions. Miss Marple looks like an ordinary old woman. She does not like a detective at all, yet with her ability to observe human nature, she can solve a murder case with her shrewd observation. Hercule Poirot is a Belgian man who has interesting physical appearance and also eccentric manners. His first appearance is in Christie’s first book, Mysterious Affair at Styles. It is difficult for someone to argue with him for he has strong character. His famous tool in identifying murder case is called “grey cells.” He always finishes each case with a dramatic denouement. 1 Maranatha Christian University In this thesis, I would like to analyse one of the many world famous Christie’s books, Towards Zero. This novel, which is a whodunit story, was written in 1944. Whodunit story is “a novel or drama concerning a crime (usually a murder) in which a detective follows clues to determine the perpetrator” (“who- dun-it”). -

THE MOVING FINGER Agatha Christie

THE MOVING FINGER Agatha Christie Chapter 1 I have often recalled the morning when the first of the anonymous letters came. It arrived at breakfast and I turned it over in the idle way one does when time goes slowly and every event must be spun out to its full extent. It was, I saw, a local letter with a typewritten address. I opened it before the two with London postmarks, since one of them was clearly a bill, and on the other I recognised the handwriting of one of my more tiresome cousins. It seems odd, now, to remember that Joanna and I were more amused by the letter than anything else. We hadn't, then, the faintest inkling of what was to come - the trail of blood and violence and suspicion and fear. One simply didn't associate that sort of thing with Lymstock. I see that I have begun badly. I haven't explained Lymstock. When I took a bad crash flying, I was afraid for a long time, in spite of soothing words from doctors and nurses, that I was going to be condemned to lie on my back all my life. Then at last they took me out of the plaster and I learned cautiously to use my limbs, and finally Marcus Kent, my doctor, clapped me on my back and told me that everything was going to be all right, but that I'd got to go and live in the country and lead the life of a vegetable for at least six months. -

The Miss Marple Reading List Uk

THE MISS MARPLE READING LIST UK Miss Jane Marple doesn’t look like your average detective, but appearances are deceiving... A shrewd woman with a sparkle in her eye, she isn’t above speculation about her neighbours in the small village of St Mary Mead. A keen advocate for justice, armed often only with her knitting needles and a pair of gardening gloves, this sleuth knows plenty about human nature. TOP FIVE MISS MARPLE NOVELS THE NOTES THE LIST Although published in 1976, Sleeping Murder was written during If you want to read the stories chronologically (in terms of World War II and portrays a sprightlier Miss Marple than Nemesis. The Miss Marple’s lifetime), we recommend the following order: title Miss Marple’s Final Cases is a misnomer, because most of the short stories are actually set (and were written) in the 1940’s. ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ is published in The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding. The Murder at the Vicarage [1930] The Thirteen Problems (short stories) [1932] Miss Marple’s Final Cases (short stories) [1979] The Body in the Library [1942] “ I’m very ordinary. An ordinary rather The Moving Finger [1942] scatty old lady. And that of course is Sleeping Murder [1976] very good camouflage.” A Murder is Announced [1950] Nemesis, Agatha Christie They Do it with Mirrors [1952] A Pocket Full of Rye [1953] ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ [1956] THE CHALLENGE 4.50 from Paddington [1957] The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side [1962] A Caribbean Mystery [1964] Keep track of your Miss Marple reading. How many stories have you read? At Bertram’s Hotel [1965] Nemesis [1971] For more reading ideas visit www.agathachristie.com THE MISS MARPLE READING LIST US Miss Jane Marple doesn’t look like your average detective, but appearances are deceiving.. -

The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie

April 26 – May 22, 2016 on the One America Mainstage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts with contributions by Janet Allen, Courtney Sale Robert M. Koharchik, Alison Heryer, Michelle Habeck, David Dabbon Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON SPONSOR 2015-2016 ASSOCIATE LEAD SPONSOR SPONSOR YOUTH AUDIENCE & PRODUCTION PARTNER FAMILY SERIES SPONSOR MATINEE PROGRAMS SPONSOR The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie Welcome to the classic Agatha Christie mystery thriller: a houseful of strangers trapped by a blizzard and stalked by an unknown murderer. The Mousetrap is the world’s longest running stage play, celebrating its 64th year in 2016. Part drawing room comedy and part murder mystery, this timeless chiller is a double-barreled whodunit full of twists and surprises. Student Matinees at 10:00 A.M. on April 28, May 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 Estimated length: 2 hours, 15 minutes, with one intermission Recommended for grades 7-12 due to mild language Themes & Topics Development of Genre Deceit and Disguise Gender and Conformity Xenophobia or Fear of the Other Logic Puzzles Contents Director’s Note 3 Executive Artistic Director’s Note 4 Designer Notes 6 Author Agatha Christie 8 10 Commandments of Detective Fiction 11 Agatha Christie’s Style 12 Other Detective Fiction 14 Academic Standards Alignment Guide 16 Pre-Show Activities 17 Discussion Questions 18 Activities 19 Writing Prompts 20 Resources 21 Glossary 23 Going to the Theatre 29 Education Sales Randy Pease • 317-916-4842 cover art by Kyle Ragsdale [email protected] Ann Marie Elliott • 317-916-4841 [email protected] Outreach Programs Milicent Wright • 317-916-4843 [email protected] Secrets by Courtney Sale, director What draws us in to the murder mystery? There is something primal yet modern about the circumstances and the settings of Agatha Christie’s stories. -

The Miss Marple Model of Psychological Assessment

THE MISS MARPLE MODEL OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Carolyn Allen Zeiger ABSTRACT The Agatha Christie detective, Miss Jane Marple, is used as a model for a particular method of doing psychological assessment. The paper demonstrates how this seemingly loose, intuitive, and informal approach is supported by a formal conceptual system. The underlying structure is delineated using concepts and tools from Descriptive Psychology. The model is articulated in terms of its procedural and conceptual features, as well as personal characteristics of the person using it. My husband and I are not television watchers, but one snowy night a couple of years ago, we were stuck at home and turned on the BBC Mystery Series. Thereupon we discovered Miss Marple, Agatha Christie's octogenarian, amateur sleuth, who just happens to show up at the right places and solve murder mysteries. Although we enjoyed all the BBC mysteries, Miss Marple was different. In her cases, I figured Advances in Descriptive Psycholoey, Volume 6, pages 159·183. Editors: Mary Kathleen Roberts and Raymond M. Bergner. Copyright 10 1991 Descriptive Psychology Press. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. ISBN: 0-9625661·1-X. 159 160 CAROLYN ALLEN ZEIGER out the mysteries. I knew what was going on. I couldn't believe it, because when it was a Sherlock Holmes mystery, I wouldn't get it. The other experience I had with Miss Marple was a strong sense of identification with her. I felt a little foolish about it, but none the less I thought, "I work just like Miss Marple, which is why she makes sense to me!" I had been worrying about not being able to articulate the way I do psychotherapy. -

Hercule Poirot Mysteries in Chronological Order

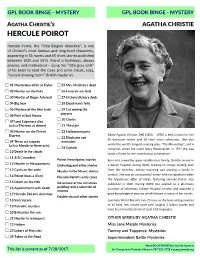

Hercule Poirot/Miss Jane Marple Christie, Agatha Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the “queen” of British mystery writers, published more than ninety stories between 1920 and 1976. Her best-loved stories revolve around two brilliant and quite dissimilar detectives, the Belgian émigré Hercule Poirot and the English spinster Miss Jane Marple. Other stories feature the “flapper” couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, the mysterious Harley Quin, the private detective Parker Pyne, or Police Superintendent Battle as investigators. Dame Agatha’s works have been adapted numerous times for the stage, movies, radio, and television. Most of the Christie mysteries are available from the New Bern-Craven County Public library in book form or audio tape. Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Murder on the Links [1923] Poirot Investigates [1924] Short story collection containing: The Adventure of "The Western Star", TheTragedy at Marsdon Manor, The Adventure of the Cheap Flat , The Mystery of Hunter's Lodge, The Million Dollar Bond Robbery, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, The Kidnapped Prime Minister, The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman, The Case of the Missing Will, The Veiled Lady, The Lost Mine, and The Chocolate Box. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] The Under Dog and Other Stories [1926] Short story collection containing: The Underdog, The Plymouth Express, The Affair at the Victory Ball, The Market Basing Mystery, The Lemesurier Inheritance, The Cornish Mystery, The King of Clubs, The Submarine Plans, and The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. The Big Four [1927] The Mystery of the Blue Train [1928] Peril at End House [1928] Lord Edgware Dies [1933] Murder on the Orient Express [1934] Three Act Tragedy [1935] Death in the Clouds [1935] The A.B.C. -

Download Poirot: Halloween Party Free Ebook

POIROT: HALLOWEEN PARTY DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Agatha Christie | 336 pages | 03 Sep 2001 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007120680 | English | London, United Kingdom 35. Hallowe'en Party (1969) - Fraser Robert Barnard : "Bobbing for apples turns serious when ghastly child Poirot: Halloween Party extinguished in the bucket. Uploaded by Unknown on September 22, All Episodes Search icon An illustration of a magnifying glass. Mrs Goodbody. However, he commits suicide when two men, recruited by Poirot to trail Miranda, thwart him and save her life. What a joy it was to find out that we were going to get Poirot: Halloween Party new Poirots this summer where I live in the US, at least. You've just tried to add this show to My List. Edit Storyline When Ariadne Oliver and Poirot: Halloween Party friend, Judith Butler, attend a children's Halloween party in the village of Woodleigh Common, a young girl named Joyce Reynolds boasts of having witnessed a murder from years before. At a Hallowe'en party held at Rowena Drake's home in Woodleigh Common, thirteen-year-old Joyce Reynolds tells everyone attending she had once seen a murder, but had not realised it was one until later. Ariadne Oliver. Director: Charlie Palmer as Charles Palmer. Visit our What to Watch page. Plot Keywords. The television adaptation shifted the late s setting to the s, as with nearly all shows in this series. The Cold War is at its peak and the opponents are hostile. External Link Explore Now. The story moves along nicely, and the whole thing is visually appealing. Read by Hugh Fraser. -

Plot of Agatha Christie's …

KULTURISTIK: Jurnal Bahasa dan Budaya Vol. 4, No. 1, Januari 2020, 56-65 PLOT OF AGATHA CHRISTIE’S … Doi: 10.22225/kulturistik.4.1.1584 PLOT OF AGATHA CHRISTIE’S THIRD GIRL Made Subur Universitas Warmadewa [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aimed to examine the parts of the plot structure and also the elements which build up the parts of the plot structure of this novel. The theory used in analyzing the data was the theory on the plot. The theoretical concepts were primarily taken from William Kenney’s book entitled How to Analyze Fiction (1996). Based on the analysis, the plot structure of Agatha Christie’s ‘Third Girl (2002) consisted of three parts: beginning plot, middle plot, and ending plot. The beginning plot of this novel told us about: (a) Hercule Poirot’s peaceful condition after having breakfast; (b) his attitude of scathing view on Edgar Allan Poe; (c) Miss. Norma’s performance with vacant expression; and (d) Hercule Poirot’s good relationship with Mrs Oliver and with Mrs Restarick. In the middle plot of this novel, the story of this novel presented about: (a) Mrs Restarick’s psychological conflict; (b) Andrew Restarick’s angriness because of David Baker’s relationship with his daughter, Miss Norma; and (c) Mrs Adriana’s unsuccessfulness to find Miss. Norma at Borodene Mansions. The events described in the complicating plot of this novel are about: (a) the investigation of Miss Norma as a suspected agent attempting to commit the murder of Mrs Restarick; (b) the secure of Miss Norma suspected to have committed murder by Dr. -

Hercule Poirot

GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY AGATHA CHRISTIE’S AGATHA CHRISTIE HERCULE POIROT Hercule Poirot, the “little Belgian detective”, is one of Christie's most famous and long-lived characters, appearing in 33 novels and 65 short stories published between 1920 and 1975. Poirot is fastidious, always precise, and methodical – using the “little gray cells” of his brain to read the clues and solve classic, cozy, “locked drawing room” British mysteries. 01 Mysterious affair at Styles 25 Mrs. McGinty's dead 02 Murder on the links 26 Funerals are fatal 03 Murder of Roger Ackroyd 27 Hickory dickory dock 04 Big four 28 Dead man's folly 05 Mystery of the blue train 29 Cat among the pigeons 06 Peril at End House 30 Clocks 07 Lord Edgeware dies (a/k/a Thirteen at dinner) 31 Third girl 08 Murder on the Orient 32 Halloween party Express Dame Agatha Christie, DBE (1890 – 1976) is best known for her 33 Elephants can 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections. She also 09 Three act tragedy remember (a/k/a Murder in three acts) wrote the world's longest-running play, “The Mousetrap”, and 6 34 Curtain romances under the name Mary Westmacott. In 1971 she was 10 Death in the clouds made a Dame for her contribution to literature. 11 A B C murders Poirot investigates: stories Born into a wealthy upper-middle-class family, Christie served in 12 Murder in Mesopotamia Underdog and other stories a Devon hospital during WWI, tending to troops coming back 13 Cards on the table Murder in the Mews: stories from the trenches, before marrying and starting a family in London. -

Re-Writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha (1979): 'An

Street, S. C. J. (2020). Re-Writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha (1979): ‘An Imaginary Solution to an Authentic Mystery’. Open Screens, 3(1), 1-30. [1]. https://doi.org/10.16995/os.34 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.16995/os.34 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via BAFTSS at http://doi.org/10.16995/os.34 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Research How to Cite: Street, S. 2020. Re-Writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha (1979): ‘An Imaginary Solution to an Authentic Mystery’. Open Screens, 3(1): 2, pp. 1–30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/os.34 Published: 09 July 2020 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Screens, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.