Female Detectives in Modern Detective Novels an Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agatha Christie

LINGOTES DE ORO Agatha Christie http://www.librodot.com Librodot Lingotes de oro Agatha Christie 2 Estos relatos son contados por los miembros del Club de los Martes que se reúnen cada semana. En la cual cada uno de los miembros y por turno expone un problema o algún misterio que cada uno conozca personalmente y del que, desde luego sepa la solución. Para así el resto del grupo poder dar con la solución del problema o misterio. El grupo esta formado por seis personas: Miss Marple, Mujer ya mayor pero especialista en resolver cualquier tipo de misterio. Raymond West: Sobrino de Miss Marple y escritor. Sir Henry Clithering: Hombre de mundo y comisionado de Scotland Yard. Doctor Pender: Anciano clérigo de parroquia Mr. Petherick: Notable abogado Joyce Lempriére: Joven artista 2 Librodot Librodot Lingotes de oro Agatha Christie 3 No se si la historia que voy a contarles es aceptable -dijo Raymond West, porque no puedo brindarles la solución. No obstante, los hechos fueron tan interesantes y tan curiosos que me gustaría proponerla como problema y, tal vez entre todos, podamos llegar a alguna conclusión lógica. »Ocurrió hace dos años, cuando fui a pasar la Pascua de Pentecostés a Cornualles con un hombre llamado John Newman. -¿Cornualles? -preguntó Joyce Lemprire con viveza. -Sí. ¿Por qué? -Por nada, sólo que es curioso. Mi historia también ocurrió en cierto lugar de Cornualles, en un pueblecito pesquero llamado Rathole. No irá usted a decirme que el suyo es el mismo. -No, el mío se llama Polperran y está situado en la costa oeste de Cornualles, un lugar agreste y rocoso. -

El Club De Los Martes

EEll CClluubb ddee llooss MMaarrtteess AGATHA CHRISTIE Misterios sin resolver. Raymond West lanzó una bocanada de humo y repitió las palabras con una especie de deliberado y consciente placer. –Misterios sin resolver. Miró satisfecho a su alrededor. La habitación era antigua, con amplias vigas oscuras que cruzaban el techo, y estaba amueblada con muebles de buena calidad muy adecuados a ella. De ahí la mirada aprobadora de Raymond West. Era escritor de profesión y le gustaba que el ambiente fuera evocador. La casa de su tía Jane siempre le había parecido un marco muy adecuado para su personalidad. Miró a través de la habitación hacia donde se encontraba ella, sentada, muy tiesa, en un gran sillón de orejas. Miss Marple vestía un traje de brocado negro, de cuerpo muy ajustado en la cintura, con una pechera blanca de encaje holandés de Mechlin. Llevaba puestos mitones también de encaje negro y un gorrito de puntilla negra recogía sus sedosos cabellos blancos.Tejía algo blanco y suave, y sus claros ojos azules, amables y benevolentes,contemplaban con placer a su sobrino y los invitados de su sobrino. Se detuvieron primero en el propio Raymond, tan satisfecho de sí mismo.Luego en Joyce Lempriére, la artista, de espesos cabellos negros y extraños ojos verdosos, y en sir Henry Clithering, el gran hombre de mundo. Había otras dos personas más en la habitación: el doctor Pender, el anciano clérigo de la parroquia; y Mr. Petherick,abogado, un enjuto hombrecillo que usaba gafas, aunque miraba por encima y no a través de los cristales. Miss Marple dedicó un momento de atención a cada una de estas personas y luego volvió a su labor con una dulce sonrisa en los labios. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background of The Study Agatha Christie is a British author in the 20th century who is famous for her novels. She is also famous for her plays, such as The Mousetrap, and short stories, such as The Submarine Plans and The Second Gong. She is considered to be one of the most famous murder mystery writers. She is clever at making stories and unforgettable detective characters. Agatha Christie has made a great contribution to the world of literature, especially in the genre of detective story. Most of her works have been filmed and the stories of her two famous detective characters, Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot, have been made into a serial in television and radio versions. Miss Marple looks like an ordinary old woman. She does not like a detective at all, yet with her ability to observe human nature, she can solve a murder case with her shrewd observation. Hercule Poirot is a Belgian man who has interesting physical appearance and also eccentric manners. His first appearance is in Christie’s first book, Mysterious Affair at Styles. It is difficult for someone to argue with him for he has strong character. His famous tool in identifying murder case is called “grey cells.” He always finishes each case with a dramatic denouement. 1 Maranatha Christian University In this thesis, I would like to analyse one of the many world famous Christie’s books, Towards Zero. This novel, which is a whodunit story, was written in 1944. Whodunit story is “a novel or drama concerning a crime (usually a murder) in which a detective follows clues to determine the perpetrator” (“who- dun-it”). -

THE MOVING FINGER Agatha Christie

THE MOVING FINGER Agatha Christie Chapter 1 I have often recalled the morning when the first of the anonymous letters came. It arrived at breakfast and I turned it over in the idle way one does when time goes slowly and every event must be spun out to its full extent. It was, I saw, a local letter with a typewritten address. I opened it before the two with London postmarks, since one of them was clearly a bill, and on the other I recognised the handwriting of one of my more tiresome cousins. It seems odd, now, to remember that Joanna and I were more amused by the letter than anything else. We hadn't, then, the faintest inkling of what was to come - the trail of blood and violence and suspicion and fear. One simply didn't associate that sort of thing with Lymstock. I see that I have begun badly. I haven't explained Lymstock. When I took a bad crash flying, I was afraid for a long time, in spite of soothing words from doctors and nurses, that I was going to be condemned to lie on my back all my life. Then at last they took me out of the plaster and I learned cautiously to use my limbs, and finally Marcus Kent, my doctor, clapped me on my back and told me that everything was going to be all right, but that I'd got to go and live in the country and lead the life of a vegetable for at least six months. -

The Miss Marple Reading List Uk

THE MISS MARPLE READING LIST UK Miss Jane Marple doesn’t look like your average detective, but appearances are deceiving... A shrewd woman with a sparkle in her eye, she isn’t above speculation about her neighbours in the small village of St Mary Mead. A keen advocate for justice, armed often only with her knitting needles and a pair of gardening gloves, this sleuth knows plenty about human nature. TOP FIVE MISS MARPLE NOVELS THE NOTES THE LIST Although published in 1976, Sleeping Murder was written during If you want to read the stories chronologically (in terms of World War II and portrays a sprightlier Miss Marple than Nemesis. The Miss Marple’s lifetime), we recommend the following order: title Miss Marple’s Final Cases is a misnomer, because most of the short stories are actually set (and were written) in the 1940’s. ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ is published in The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding. The Murder at the Vicarage [1930] The Thirteen Problems (short stories) [1932] Miss Marple’s Final Cases (short stories) [1979] The Body in the Library [1942] “ I’m very ordinary. An ordinary rather The Moving Finger [1942] scatty old lady. And that of course is Sleeping Murder [1976] very good camouflage.” A Murder is Announced [1950] Nemesis, Agatha Christie They Do it with Mirrors [1952] A Pocket Full of Rye [1953] ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ [1956] THE CHALLENGE 4.50 from Paddington [1957] The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side [1962] A Caribbean Mystery [1964] Keep track of your Miss Marple reading. How many stories have you read? At Bertram’s Hotel [1965] Nemesis [1971] For more reading ideas visit www.agathachristie.com THE MISS MARPLE READING LIST US Miss Jane Marple doesn’t look like your average detective, but appearances are deceiving.. -

The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie

April 26 – May 22, 2016 on the One America Mainstage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts with contributions by Janet Allen, Courtney Sale Robert M. Koharchik, Alison Heryer, Michelle Habeck, David Dabbon Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON SPONSOR 2015-2016 ASSOCIATE LEAD SPONSOR SPONSOR YOUTH AUDIENCE & PRODUCTION PARTNER FAMILY SERIES SPONSOR MATINEE PROGRAMS SPONSOR The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie Welcome to the classic Agatha Christie mystery thriller: a houseful of strangers trapped by a blizzard and stalked by an unknown murderer. The Mousetrap is the world’s longest running stage play, celebrating its 64th year in 2016. Part drawing room comedy and part murder mystery, this timeless chiller is a double-barreled whodunit full of twists and surprises. Student Matinees at 10:00 A.M. on April 28, May 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 Estimated length: 2 hours, 15 minutes, with one intermission Recommended for grades 7-12 due to mild language Themes & Topics Development of Genre Deceit and Disguise Gender and Conformity Xenophobia or Fear of the Other Logic Puzzles Contents Director’s Note 3 Executive Artistic Director’s Note 4 Designer Notes 6 Author Agatha Christie 8 10 Commandments of Detective Fiction 11 Agatha Christie’s Style 12 Other Detective Fiction 14 Academic Standards Alignment Guide 16 Pre-Show Activities 17 Discussion Questions 18 Activities 19 Writing Prompts 20 Resources 21 Glossary 23 Going to the Theatre 29 Education Sales Randy Pease • 317-916-4842 cover art by Kyle Ragsdale [email protected] Ann Marie Elliott • 317-916-4841 [email protected] Outreach Programs Milicent Wright • 317-916-4843 [email protected] Secrets by Courtney Sale, director What draws us in to the murder mystery? There is something primal yet modern about the circumstances and the settings of Agatha Christie’s stories. -

The Miss Marple Model of Psychological Assessment

THE MISS MARPLE MODEL OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Carolyn Allen Zeiger ABSTRACT The Agatha Christie detective, Miss Jane Marple, is used as a model for a particular method of doing psychological assessment. The paper demonstrates how this seemingly loose, intuitive, and informal approach is supported by a formal conceptual system. The underlying structure is delineated using concepts and tools from Descriptive Psychology. The model is articulated in terms of its procedural and conceptual features, as well as personal characteristics of the person using it. My husband and I are not television watchers, but one snowy night a couple of years ago, we were stuck at home and turned on the BBC Mystery Series. Thereupon we discovered Miss Marple, Agatha Christie's octogenarian, amateur sleuth, who just happens to show up at the right places and solve murder mysteries. Although we enjoyed all the BBC mysteries, Miss Marple was different. In her cases, I figured Advances in Descriptive Psycholoey, Volume 6, pages 159·183. Editors: Mary Kathleen Roberts and Raymond M. Bergner. Copyright 10 1991 Descriptive Psychology Press. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. ISBN: 0-9625661·1-X. 159 160 CAROLYN ALLEN ZEIGER out the mysteries. I knew what was going on. I couldn't believe it, because when it was a Sherlock Holmes mystery, I wouldn't get it. The other experience I had with Miss Marple was a strong sense of identification with her. I felt a little foolish about it, but none the less I thought, "I work just like Miss Marple, which is why she makes sense to me!" I had been worrying about not being able to articulate the way I do psychotherapy. -

A Caribbean Mystery: Complete & Unabridged Pdf, Epub, Ebook

A CARIBBEAN MYSTERY: COMPLETE & UNABRIDGED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Agatha Christie,Joan Hickson | none | 22 Apr 2003 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007161072 | English | London, United Kingdom A Caribbean Mystery: Complete & Unabridged PDF Book Ett delat mysterium Sophie Hannah, Agatha Christie. Learn more about possible network issues or contact support for more help. If you receive an error message, please contact your library for help. But each page has excerpts from her writing, and often other tidbits such as highlighting dates that her plays opened etc. Add it now to start borrowing from the collection. I began maintaining a spreadsheet but it quickly became messy with all the variants. Need a card? The other is ornithologist James Bond Charlie Higson , who begins a lecture to his fellow guests by introducing himself as " Webb , formerly an assistant director at 20th Century Fox. Tim Kendal : A man in his thirties married to Molly Kendal, who marries her using false references and starts the hotel with her, using her money. Thank you so much for sharing those details — and you have definitely found an audience here with the same fascination for solving literary mysteries and finding all these little details! The last diary was printed in She has the LE version…….. Add a library card to your account to borrow titles, place holds, and add titles to your wish list. Tim put belladonna in Molly's cosmetics to make her appear mad to the others. A few minutes before twelve, he hears whistling from the garden, goes to the door, and narrowly misses a dagger being thrown at him. -

CHRISTIE, Agatha

CHRISTIE, Agatha Geboren als: Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller, Torquay, Devon, Engeland, 15 september 1890 Overleden: Wallingford, Oxfordshire, 12 januari 1976 Pseudoniem: Mary Westmacott Opleiding: privé-opleiding thuis; studeerde zang en piano in Parijs Militaire dienst: diende als vrijwillig verpleegster in een Rode Kruis ziekenhuis in Torquay gedurende de Eerste Wereldoorlog en in de legerapotheek van het University College Hospital in Londen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog; Carrière: assisteerde haar echtgenoot Max Mallowan bij opgravingen in Irak en Syrië en bij de Assyrische steden; president van de Detection Club in 1954. Onderscheidingen: Mystery Writers of America Grand Master award, 1954; New York Drama Critics Circle award, 1955; Doctor of Letters (D.Litt), University of Exeter, 1961; C.B.E. (Commander, Order of the British Empire), 1956; D.B.E. (Dame, Order of the British Empire), 1971. Familie: getrouwd met 1. Kolonel Archibald Christie, 1914 (gescheiden, 1928, overleden, 1962); 1 dochter Rosalind, 1919; 2. de archeolooog Sir Max Mallowan in 1930 (overleden, 1978) Op 4 december 1926 verdween Christie enkele dagen op mysterieuze wijze; zij heeft nooit onthuld wat er gedurende die dagen is gebeurd. (foto: Fantastic Fiction) detective: Hercule Poirot , privé-detective, Londen Poirot is een voormalig Belgisch politieman, gevlucht tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog, later privé-detective in Londen. Hij is een kleine, vormelijke man met een hoofd als een ei, een gepommadeerde snor en is geobsedeerd door netheid, orde en methode. Hij was aanvankelijk in dienst bij de Belgische politie, maar ging met pensioen en werd in 1916, gedurende de eerste wereldoorlog naar Engeland gesmokkeld, waar hij zijn kennismaking hernieuwde met Captain Arthur Hastings, die hij in België al ontmoet had. -

The Thirteen Problems

An introduction to The Thirteen Problems Mathew Prichard The Thirteen Problems introduces Miss Marple and the world of St. Mary Mead to crime fiction. It began life as a series of six stories written for ‘Sketch’ magazine in 1928 and was later expanded into the full thirteen and published in 1932. It centres on a group of people who meet once a week to discuss unsolved crimes drawn from their own past. Over the course of two mystery evenings, Miss Marple’s close circle of friends and neighbours’ are developed into the fully rounded characters, now so familiar to Christie readers. It is here that we meet the authoritative ex-commissioner Henry Clithering; respectable clergyman Dr Pender; local solicitor Mr Petherick; upright Colonel Bantry and his wife Dolly and Miss Marple’s nephew – Raymond West. I think that taken together, this collection of short stories encapsulates the quintessential Miss Marple mystery. Time and again, despite the learned intellect and worldly knowledge of the assembled party, it is the sweet old lady in the corner, seemingly absorbed in her knitting, who cuts to the core of every heinous crime, uncovering murderous intent with startling accuracy and apparent ease. It is a tantalising challenge to orthodox assumptions about cosy village life and harmless little old ladies. Like Agatha Christie herself, Miss Marple certainly defies all stereotypes. A gentle woman whose ‘faded blue eyes; benignant and kindly’ conceal a fierce intellect and powerful intuition. She never actually lays claim to any great detective powers herself, but possesses a fundamental understanding of people and their weaknesses. -

Hercule Poirot Mysteries in Chronological Order

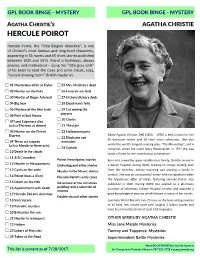

Hercule Poirot/Miss Jane Marple Christie, Agatha Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the “queen” of British mystery writers, published more than ninety stories between 1920 and 1976. Her best-loved stories revolve around two brilliant and quite dissimilar detectives, the Belgian émigré Hercule Poirot and the English spinster Miss Jane Marple. Other stories feature the “flapper” couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, the mysterious Harley Quin, the private detective Parker Pyne, or Police Superintendent Battle as investigators. Dame Agatha’s works have been adapted numerous times for the stage, movies, radio, and television. Most of the Christie mysteries are available from the New Bern-Craven County Public library in book form or audio tape. Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Murder on the Links [1923] Poirot Investigates [1924] Short story collection containing: The Adventure of "The Western Star", TheTragedy at Marsdon Manor, The Adventure of the Cheap Flat , The Mystery of Hunter's Lodge, The Million Dollar Bond Robbery, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, The Kidnapped Prime Minister, The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman, The Case of the Missing Will, The Veiled Lady, The Lost Mine, and The Chocolate Box. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] The Under Dog and Other Stories [1926] Short story collection containing: The Underdog, The Plymouth Express, The Affair at the Victory Ball, The Market Basing Mystery, The Lemesurier Inheritance, The Cornish Mystery, The King of Clubs, The Submarine Plans, and The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. The Big Four [1927] The Mystery of the Blue Train [1928] Peril at End House [1928] Lord Edgware Dies [1933] Murder on the Orient Express [1934] Three Act Tragedy [1935] Death in the Clouds [1935] The A.B.C. -

Hercule Poirot

GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY AGATHA CHRISTIE’S AGATHA CHRISTIE HERCULE POIROT Hercule Poirot, the “little Belgian detective”, is one of Christie's most famous and long-lived characters, appearing in 33 novels and 65 short stories published between 1920 and 1975. Poirot is fastidious, always precise, and methodical – using the “little gray cells” of his brain to read the clues and solve classic, cozy, “locked drawing room” British mysteries. 01 Mysterious affair at Styles 25 Mrs. McGinty's dead 02 Murder on the links 26 Funerals are fatal 03 Murder of Roger Ackroyd 27 Hickory dickory dock 04 Big four 28 Dead man's folly 05 Mystery of the blue train 29 Cat among the pigeons 06 Peril at End House 30 Clocks 07 Lord Edgeware dies (a/k/a Thirteen at dinner) 31 Third girl 08 Murder on the Orient 32 Halloween party Express Dame Agatha Christie, DBE (1890 – 1976) is best known for her 33 Elephants can 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections. She also 09 Three act tragedy remember (a/k/a Murder in three acts) wrote the world's longest-running play, “The Mousetrap”, and 6 34 Curtain romances under the name Mary Westmacott. In 1971 she was 10 Death in the clouds made a Dame for her contribution to literature. 11 A B C murders Poirot investigates: stories Born into a wealthy upper-middle-class family, Christie served in 12 Murder in Mesopotamia Underdog and other stories a Devon hospital during WWI, tending to troops coming back 13 Cards on the table Murder in the Mews: stories from the trenches, before marrying and starting a family in London.