When Parody and Reality Collide: Examining the Effects of Colbert's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

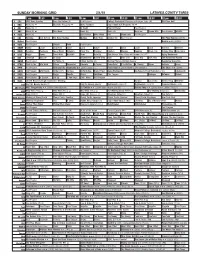

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

The 60Th Annual New York Emmy® Award Nominations Announced This Morning!

THE 60TH ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THIS MORNING! MSG Network Gets the Most Nominations with 54 New York, NY – Thursday, February 23, 2017. The 60th Annual New York Emmy® Award nominations took place this afternoon at the studios of CUNY-TV. Hosting the announcement was Denise Rover, President, NY NATAS. Presenting the nominees were Emmy® Award-winner N.J. Burkett, Correspondent, WABC-TV; Emmy® Award-winner Marvin Scott, Senior Correspondent and Anchor/Host, PIX News Close Up, WPIX-TV; Emmy® Award-winner Elizabeth Hashagen, Anchor, News 12 Long Island; and Emmy® Award-winner, Diana Williams, Anchor, Eyewitness News at 5 PM, WABC-TV Total Number of Nominated Entries MSG Network 54 NJ.com 3 WNBC-TV 50 WXXI Public Broadcasting 3 WPIX-TV 44 NYDailyNews.com 2 YES Network 34 WCNY Syracuse 2 WXTV Univision 41 33 WMHT-TV 2 WNJU Telemundo 47 31 WXXA 2 Newsday 25 Zagat 2 SNY 25 abc7ny.com 1 News 12 Long Island 23 APTV / Asbury Park Television 1 WNYW FOX 5 19 Azteca America 1 News 12 Connecticut 17 BARD Entertainment 1 News 12 Westchester 14 cbsnewyork.com 1 WCBS-TV 14 ESN-TV Cablevision Channel 118 1 BRIC TV 13 Greenburgh Cable Access Television 1 Thirteen/WNET 12 HuffingtonPost.com 1 CUNY-TV 11 MSGNetworks.com 1 WABC-TV 11 NET TV 1 WLIW 10 News 12 Brooklyn 1 MSG+ 10 News 12 Interactive 1 NJTV 9 News 12 The Bronx 1 NYC Life 8 NewYorkLiveTV.com 1 News 12 New Jersey 7 NY1 Noticias 1 Time Warner Cable News - Albany 7 NY1Noticias.com 1 Time Warner Cable News - Rochester 7 PCK Media/NJTV 1 WTEN-TV 7 PIX11.com 1 Brooklyn Free Speech 6 SNY.tv 1 Elite Daily 6 SYR.edu 1 FiOS1 News 5 Telemundo47.com 1 WGRZ-TV 5 The Players Tribune & Spacestation 1 WHEC-TV 5 Thirteen.org 1 WIVB-TV 5 Time Warner Cable SportsChannel 1 WRGB-TV 5 WGRZ.com 1 Yankees.com 5 WJLP-TV 1 Vox Media/Eater.com 4 WNED-TV 1 WSTM-TV 4 WRNN-TV 1 GAF 3 WROC-TV 1 HITN 3 The 60th Annual New York Emmy® Awards will be presented at a Black-Tie Gala on Saturday, May 6, 2017 at The Marriott® Marquis ~ Times Square. -

Businesses Brace for Energy Cost Increases

newsJUNE 2011 We all influence the health of those around us, especially in the work place. As an employer, you have a tremendous effect on employee health by the examples you set and the health care plans you choose. As a Kentucky Chamber Businesses member, you’re connected to big savings on big benefits for your small business. Help employees get more involved in their health care with consumer-driven HSA, HRA and HIA plans, or choose from more traditional solutions. Either way, brace for you can build a complete benefits package – including preventive care and prescription coverage – with one-stop shopping convenience. energy cost Talk to your broker, call the Kentucky Chamber at 800-431-6833 or visit increases group.anthem.com/kcoc for more information. PAGE 1 Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield is the trade name of Anthem Health Plans of Kentucky, Inc. Life and Disability products underwritten by Anthem Life Insurance Company. Independent licensees of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. ® ANTHEM is a registered trademark of Anthem Insurance Companies, Inc. The Blue Cross and Blue Shield names and symbols are registered marks of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. 19075KYAENABS 1/11 JUNE 2011 Business Summit and Annual Meeting Businesses Morning Joe hosts brace for to share their views energy cost at Annual Meeting ONE OF CABLE television’s highest rated morning increases talk shows, MSNBC’s Morning Joe, is not just a NEW DATA from Kentucky’s regulated news source — it’s also been, at times, a newsmak- electric utility companies shows that the er. -

Ruth Marcus Experience The

RUTH MARCUS EXPERIENCE THE WASHINGTON POST 2016-Present: Deputy editorial page editor. Oversee oped pages and all signed opinion content. Review oped submissions, hire and manage columnists and bloggers, develop multi- platform content including video, chart strategic direction of opinion section and develop digital strategy. As member of editorial board attend editorial board meetings and help shape editorial positions. 2006-Present: Columnist. Write opinion column for oped page and, beginning in 2008, for syndicated newspaper clients, focusing on domestic politics and policy. Finalist, Pulitzer Prize for commentary, 2007. “The week” columnist of the year, 2008. 2003-2015: Editorial writer. Write editorials on domestic policy and politics, including budget and taxes, health care, money and politics. 1999-2003: Deputy National Editor. Oversee staff coverage of campaign finance and lobbying and national politics; direct coverage of 2000 recount. 1986-1999: National Staff Reporter covering White House, Supreme Court, Justice Department, national politics, money and politics. 1984-1987: Metro staff reporter covering local development and legal issues. Wrote weekly column on law and lawyers. Covered “Year of the Spy” espionage cases. EXTRACURRICULAR: 2017-Present: MSNBC/NBC news contributor. Appear several times weekly on MSBC shows, including Morning Joe, Andrea Mitchell Reports, Hardball, Last Word, Meet the Press and Meet the Press Daily. Previously: Regular guest on ABC’s “This Week,” CBS “Face the Nation,” CNN, Fox News Frequent guest and moderator on panels, including Atlantic Festival, Aspen Ideas Festival, New Yorker Festival, Brookings Institution. EDUCATION 1981-1984: Harvard Law School, magna cum laude, Harvard Law Review 1975-1979: Yale College, cum laude, with distinction in history Error! Bookmark not defined. -

Fiduciary Duty and the Public Interest

FIDUCIARY DUTY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST CHERYL L. WADE∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1191 I. SUBPRIME LENDERS, SHAREHOLDERS, CONSUMERS, AND COMMUNITIES ................................................................................... 1193 II. PREDATORY LENDERS AND THE FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS THAT DID BUSINESS WITH THEM ................................................................ 1196 III. PUBLIC OPINION, DISCOURSE, AND FIDUCIARY DUTY. ...................... 1203 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................. 1207 INTRODUCTION Professor Tamar Frankel’s excellent book, Fiduciary Law, is a thorough and comprehensive look at the fiduciary-law forest. My contribution to the Symposium on The Role of Fiduciary Law and Trust in the Twenty-First Century is one leaf on one branch of one tree in the forest that Professor Frankel so expertly navigates. In this Essay, I explore the fiduciary relationship between corporate directors and officers and the shareholders they serve. I examine how the breach of fiduciary duties owed to shareholders has the power to dramatically impact non-shareholder groups. Professor Frankel accurately observes that “[f]iduciary duties are anchored in the interests of the parties to the relationship rather than the public’s interests.”1 But her statement ignores the expansive reach and impact of fiduciary law in general and fiduciary duty breach in particular. Corporate fiduciaries’ -

National,Network Cable Spot Daily Calendar

Spot Daily Calendar National,Network Cable Client: Coalition to Protect Americas Health Care Flight Dates: Monday, March 24, 2014 to Sunday, March 30, 2014 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 03/24/14 03/25/14 03/26/14 03/27/14 03/28/14 03/29/14 03/30/14 Early Morning Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Daytime Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN CNN-TV: CNN Newsroom 9am Newsroom 9am 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 1 x 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 1 x Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News Daytime Daytime Daytime Daytime 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN News CNN-TV: CNN News CNN-TV: CNN News Daytime Daytime Daytime 10:00 AM -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

MSNBC HD Now Available Nationwide on DISH Network

MSNBC HD Now Available Nationwide on DISH Network Englewood, Colo. – July 9, 2009 – DISH Network today introduced MSNBC HD, becoming the first pay-TV provider to offer the channel to consumers nationwide. “As the leader in high definition programming with more than 140 national HD channels, we are pleased to be the only pay-TV provider to offer MSNBC HD nationwide,”said Dave Shull, senior vice president of Programming for DISH Network. “Nowhere else will consumers find the variety of HD programming and award-winning DVR technology at the low everyday prices that DISH Network offers.” “MSNBC is in the best competitive place it’s ever been, beating CNN in primetime and continuing incredible growth,”said Phil Griffin, President, MSNBC. “Broadcasting in HD is only going to help us build on the great success we’ve had so far this year, and will give viewers what they’ve been asking for, a full high definition broadcast of MSNBC.” DISH Network customers will now be able to watch MSNBC's popular primetime programming in full high definition, including the highly rated and critically acclaimed "Countdown with Keith Olbermann," "The Rachel Maddow Show," "Hardball with Chris Matthews," and the smartest morning show on television, "Morning Joe." MSNBC HD is located on DISH Network Ch. 209 in Classic Silver 200 with HD and above, available to customers starting at $22.99 per month for the first six months, along with free installation, a free HD DVR and three months of free premium channels, including HBO and Showtime. For more information about DISH Network, visit www.dishnetwork.com. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

MSNBC Launches on SIRIUS XM Radio

MSNBC Launches on SIRIUS XM Radio --From 'Morning Joe' in morning drive to primetime with Olbermann, Matthews and Maddow --World-class reporting, personalities, the latest issues and news available to millions of listeners NEW YORK, April 7, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX News Network/ -- SIRIUS XM Radio (Nasdaq: SIRI) and MSNBC today announced that beginning April 12, SIRIUS XM will carry MSNBC, offering millions of subscribers across the country access to the channel's world-class reporting, full schedule of live news coverage, political analysis and award-winning documentary programming. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20080819/NYTU044LOGO ) MSNBC will air on SIRIUS channel 90 and XM channel 120. "We welcome MSNBC's dynamic lineup of shows and hosts to SIRIUS XM," said Scott Greenstein, President and Chief Content Officer, SIRIUS XM Radio. "At virtually every time of day and evening, MSNBC provides compelling and entertaining commentary and news. Now millions of listeners can stay connected via SIRIUS XM to their favorite source for news, politics, and the singular personalities of MSNBC wherever they go." "We're thrilled to have MSNBC's programming available to SIRIUS XM's millions of listeners," said Phil Griffin, President of MSNBC. "We know our viewers will appreciate the ability to take MSNBC with them when they're away from the TV, from 'Morning Joe' on the way to the office to our opinion programs on the way home to breaking news anytime." The MSNBC channel on SIRIUS XM programming lineup includes: ● "Way Too Early" with -

Daniela Pierre-Bravo Teaches Us How to 'Earn It'

Daniela Pierre-Bravo Teaches Us How to 'Earn It' Daniela Pierre-Bravo has never met an obstacle more formidable than her will. Disqualified from college scholarships due to her legal status, she built a thriving local Mary Kay business to pay for it. Invited to an interview for an unpaid internship in NYC, she took an 18-hour overnight bus from Ohio and showed up the next morning. And nailed it. Now And now she's the coauthor of the new book, Earn It: A Career Guide for Women in Their Twenties and Beyond with MSNBC Morning Joe host Mika Brzezinski. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Alicia Menendez: Hey. For those of you who follow us on Instagram or Twitter, you may already know this, but for those of you who don't, we have merch. We have a brand new mug, perfect for your morning coffee con leche or matcha tea or whatever it is you're into. We've got these canvas pouches that you can use to organize your bag, put in your headphones, your lipstick. And then, we have these sticker sets that you can put wherever you want. I have mine on my laptop. I love it. My laptop feels so much cooler. We'd be so grateful if you headed over to latinatoLatina.com/shop. Check it out. Buy one for yourself, for your friend, for your favorite listener. Again, we love you. We love being able to do this for you, and creating a product at this level requires things like studio time, sound engineer, and so, a little bit of support will really go a long way. -

THE COLOR of NEWS: How Different Media Have Covered the General Election

THE COLOR OF NEWS: How Different Media Have Covered the General Election When it comes to coverage of the campaign for president 2008, where one goes for news makes a difference, according to a new study. In cable, the evidence firmly suggests there now really is an ideological divide between two of the three channels, at least in their coverage of the campaign. Things look much better for Barack Obama—and much worse for John McCain—on MSNBC than in most other news outlets. On the Fox News Channel, the coverage of the presidential candidates is something of a mirror image of that seen on MSNBC. The tone of CNN’s coverage, meanwhile, lay somewhere in the middle of the cable spectrum, and was generally more negative than the press overall. On the evening newscasts of the three traditional networks, in contrast, there is no such ideological split. Indeed, on the nightly newscasts of ABC, CBS and NBC, coverage tends to be more neutral and generally less negative than elsewhere. On the network morning shows, Sarah Palin is a bigger story than she is in the media generally. And on NBC News programs, there was no reflection of the tendency of its cable sibling MSNBC toward more favorable coverage of Democrats and more negative of Republicans than the norm. Online, meanwhile, polling tended to drive the news. And on the front pages of newspapers, which often have the day-after story, things look tougher for John McCain than they tend to in the media overall. 1 These are some of the findings of the study, which examined 2,412 stories from 48 outlets during the time period from September 8 to October 16.1 The report is a companion to a study released October 22 about the tone of coverage overall.