Fiduciary Duty and the Public Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Businesses Brace for Energy Cost Increases

newsJUNE 2011 We all influence the health of those around us, especially in the work place. As an employer, you have a tremendous effect on employee health by the examples you set and the health care plans you choose. As a Kentucky Chamber Businesses member, you’re connected to big savings on big benefits for your small business. Help employees get more involved in their health care with consumer-driven HSA, HRA and HIA plans, or choose from more traditional solutions. Either way, brace for you can build a complete benefits package – including preventive care and prescription coverage – with one-stop shopping convenience. energy cost Talk to your broker, call the Kentucky Chamber at 800-431-6833 or visit increases group.anthem.com/kcoc for more information. PAGE 1 Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield is the trade name of Anthem Health Plans of Kentucky, Inc. Life and Disability products underwritten by Anthem Life Insurance Company. Independent licensees of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. ® ANTHEM is a registered trademark of Anthem Insurance Companies, Inc. The Blue Cross and Blue Shield names and symbols are registered marks of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. 19075KYAENABS 1/11 JUNE 2011 Business Summit and Annual Meeting Businesses Morning Joe hosts brace for to share their views energy cost at Annual Meeting ONE OF CABLE television’s highest rated morning increases talk shows, MSNBC’s Morning Joe, is not just a NEW DATA from Kentucky’s regulated news source — it’s also been, at times, a newsmak- electric utility companies shows that the er. -

When Parody and Reality Collide: Examining the Effects of Colbert's

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 394–413 1932–8036/20130005 When Parody and Reality Collide: Examining the Effects of Colbert’s Super PAC Satire on Issue Knowledge and Policy Engagement Across Media Formats HEATHER LAMARRE University of Minnesota See the companion work to this article “Shifting the Conversation: Colbert’s Super PAC and the Measurement of Satirical Efficacy” by Amber Day in this Special Section Following the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court landmark decision on campaign finance (i.e., Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission), political comedian Stephen Colbert took to the airways with a new kind of entertainment-based political commentary; satirical political activism. Colbert’s creation of a super PAC garnered the attention of national media, providing him the opportunity to move his satire beyond the confines of his late- night comedy show (The Colbert Report). Transcending traditional boundaries of late- night political comedy, Colbert appeared in character on a variety of political talk shows. Meta-coverage of this collision between parody and reality begs the question: Do audiences who consume Colbert’s super PAC parody in different media contexts demonstrate significantly different effects? Using data from a Web-based experiment (N = 112), effects of consuming Colbert’s super PAC satire in different media contexts (political comedy show, political talk show) were compared. Results indicate that consuming Colbert’s super PAC parody in the context of his comedy show resulted in significantly higher levels of issue knowledge and support for campaign finance reform when compared with those who consumed Colbert’s super PAC parody in the context of a political talk show (Morning Joe). -

Ruth Marcus Experience The

RUTH MARCUS EXPERIENCE THE WASHINGTON POST 2016-Present: Deputy editorial page editor. Oversee oped pages and all signed opinion content. Review oped submissions, hire and manage columnists and bloggers, develop multi- platform content including video, chart strategic direction of opinion section and develop digital strategy. As member of editorial board attend editorial board meetings and help shape editorial positions. 2006-Present: Columnist. Write opinion column for oped page and, beginning in 2008, for syndicated newspaper clients, focusing on domestic politics and policy. Finalist, Pulitzer Prize for commentary, 2007. “The week” columnist of the year, 2008. 2003-2015: Editorial writer. Write editorials on domestic policy and politics, including budget and taxes, health care, money and politics. 1999-2003: Deputy National Editor. Oversee staff coverage of campaign finance and lobbying and national politics; direct coverage of 2000 recount. 1986-1999: National Staff Reporter covering White House, Supreme Court, Justice Department, national politics, money and politics. 1984-1987: Metro staff reporter covering local development and legal issues. Wrote weekly column on law and lawyers. Covered “Year of the Spy” espionage cases. EXTRACURRICULAR: 2017-Present: MSNBC/NBC news contributor. Appear several times weekly on MSBC shows, including Morning Joe, Andrea Mitchell Reports, Hardball, Last Word, Meet the Press and Meet the Press Daily. Previously: Regular guest on ABC’s “This Week,” CBS “Face the Nation,” CNN, Fox News Frequent guest and moderator on panels, including Atlantic Festival, Aspen Ideas Festival, New Yorker Festival, Brookings Institution. EDUCATION 1981-1984: Harvard Law School, magna cum laude, Harvard Law Review 1975-1979: Yale College, cum laude, with distinction in history Error! Bookmark not defined. -

National,Network Cable Spot Daily Calendar

Spot Daily Calendar National,Network Cable Client: Coalition to Protect Americas Health Care Flight Dates: Monday, March 24, 2014 to Sunday, March 30, 2014 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 03/24/14 03/25/14 03/26/14 03/27/14 03/28/14 03/29/14 03/30/14 Early Morning Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & FXNC-TV: Fox & Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC Ch MSNBC MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe MNBC-TV: Morning Joe 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Daytime Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New CNN-TV: CNN New Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News Day Morning News 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 2 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x 6:00 AM 9:00 AM 1 x Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN CNN-TV: CNN Newsroom 9am Newsroom 9am 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 1 x 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 1 x Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews Ch FoxNews FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News FXNC-TV: Fox News Daytime Daytime Daytime Daytime 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x 9:00 AM 12:00 PM 1 x Ch CNN Ch CNN Ch CNN CNN-TV: CNN News CNN-TV: CNN News CNN-TV: CNN News Daytime Daytime Daytime 10:00 AM -

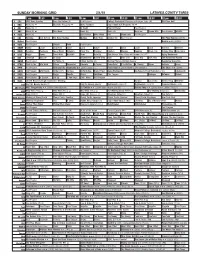

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

MSNBC HD Now Available Nationwide on DISH Network

MSNBC HD Now Available Nationwide on DISH Network Englewood, Colo. – July 9, 2009 – DISH Network today introduced MSNBC HD, becoming the first pay-TV provider to offer the channel to consumers nationwide. “As the leader in high definition programming with more than 140 national HD channels, we are pleased to be the only pay-TV provider to offer MSNBC HD nationwide,”said Dave Shull, senior vice president of Programming for DISH Network. “Nowhere else will consumers find the variety of HD programming and award-winning DVR technology at the low everyday prices that DISH Network offers.” “MSNBC is in the best competitive place it’s ever been, beating CNN in primetime and continuing incredible growth,”said Phil Griffin, President, MSNBC. “Broadcasting in HD is only going to help us build on the great success we’ve had so far this year, and will give viewers what they’ve been asking for, a full high definition broadcast of MSNBC.” DISH Network customers will now be able to watch MSNBC's popular primetime programming in full high definition, including the highly rated and critically acclaimed "Countdown with Keith Olbermann," "The Rachel Maddow Show," "Hardball with Chris Matthews," and the smartest morning show on television, "Morning Joe." MSNBC HD is located on DISH Network Ch. 209 in Classic Silver 200 with HD and above, available to customers starting at $22.99 per month for the first six months, along with free installation, a free HD DVR and three months of free premium channels, including HBO and Showtime. For more information about DISH Network, visit www.dishnetwork.com. -

MSNBC Launches on SIRIUS XM Radio

MSNBC Launches on SIRIUS XM Radio --From 'Morning Joe' in morning drive to primetime with Olbermann, Matthews and Maddow --World-class reporting, personalities, the latest issues and news available to millions of listeners NEW YORK, April 7, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX News Network/ -- SIRIUS XM Radio (Nasdaq: SIRI) and MSNBC today announced that beginning April 12, SIRIUS XM will carry MSNBC, offering millions of subscribers across the country access to the channel's world-class reporting, full schedule of live news coverage, political analysis and award-winning documentary programming. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20080819/NYTU044LOGO ) MSNBC will air on SIRIUS channel 90 and XM channel 120. "We welcome MSNBC's dynamic lineup of shows and hosts to SIRIUS XM," said Scott Greenstein, President and Chief Content Officer, SIRIUS XM Radio. "At virtually every time of day and evening, MSNBC provides compelling and entertaining commentary and news. Now millions of listeners can stay connected via SIRIUS XM to their favorite source for news, politics, and the singular personalities of MSNBC wherever they go." "We're thrilled to have MSNBC's programming available to SIRIUS XM's millions of listeners," said Phil Griffin, President of MSNBC. "We know our viewers will appreciate the ability to take MSNBC with them when they're away from the TV, from 'Morning Joe' on the way to the office to our opinion programs on the way home to breaking news anytime." The MSNBC channel on SIRIUS XM programming lineup includes: ● "Way Too Early" with -

Daniela Pierre-Bravo Teaches Us How to 'Earn It'

Daniela Pierre-Bravo Teaches Us How to 'Earn It' Daniela Pierre-Bravo has never met an obstacle more formidable than her will. Disqualified from college scholarships due to her legal status, she built a thriving local Mary Kay business to pay for it. Invited to an interview for an unpaid internship in NYC, she took an 18-hour overnight bus from Ohio and showed up the next morning. And nailed it. Now And now she's the coauthor of the new book, Earn It: A Career Guide for Women in Their Twenties and Beyond with MSNBC Morning Joe host Mika Brzezinski. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Alicia Menendez: Hey. For those of you who follow us on Instagram or Twitter, you may already know this, but for those of you who don't, we have merch. We have a brand new mug, perfect for your morning coffee con leche or matcha tea or whatever it is you're into. We've got these canvas pouches that you can use to organize your bag, put in your headphones, your lipstick. And then, we have these sticker sets that you can put wherever you want. I have mine on my laptop. I love it. My laptop feels so much cooler. We'd be so grateful if you headed over to latinatoLatina.com/shop. Check it out. Buy one for yourself, for your friend, for your favorite listener. Again, we love you. We love being able to do this for you, and creating a product at this level requires things like studio time, sound engineer, and so, a little bit of support will really go a long way. -

Nbc News, Msnbc, Cnbc and Telemundo Take a Special Look at Education with Dedicated Programming and Cross Network Coverage of Nbc's "Education Nation"

NBC NEWS, MSNBC, CNBC AND TELEMUNDO TAKE A SPECIAL LOOK AT EDUCATION WITH DEDICATED PROGRAMMING AND CROSS NETWORK COVERAGE OF NBC'S "EDUCATION NATION" The Conversation Continues Online as EducationNation.com and iVillage Engage Teachers and Parents New York, NY - September 21 - NBC News, MSNBC, CNBC and Telemundo will provide cross network on-air coverage of NBC's "Education Nation” with a series of special reports, programming and live events starting Sunday, September 26. The conversation will continue online with special features and reports at MSNBC.com, EducationNation.com and iVillage. Throughout the week, "Today's" team of anchors and correspondents will provide daily reports on a variety of different schools from across the country. Each anchor will explore a different age group and the challenges they face. "Today" also will host a Teacher Roundtable and a Parents' Workshop, and report on topics such as the value of learning a second language and the opportunities of vocational schools. On Sunday’s edition of "Meet the Press," David Gregory will moderate a special panel that will include Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, live from Rockefeller Plaza. On "Nightly News with Brian Williams," Education Correspondent Rehema Ellis will explore both the "Race to the Top" project in the U.S., and the secrets behind education success in Finland—where students rank number one in the world. Tom Brokaw will take a closer look at the Gates Foundation's multimillion-dollar research project on teacher effectiveness, and Lester Holt will analyze new technologies and their use in transforming classrooms. "Nightly News" will anchor live from "Education Nation" on Rockefeller Plaza during the summit. -

ENEMY CONSTRUCTION and the PRESS Ronnell Andersen Jones* & Lisa Grow Sun†

ENEMY CONSTRUCTION AND THE PRESS RonNell Andersen Jones* & Lisa Grow Sun† ABSTRACT When the President of the United States declared recently that the press is “the enemy,” it set off a firestorm of criticism from defenders of the institutional media and champions of the press’s role in the democracy. But even these Trump critics have mostly failed to appreciate the wider ramifications of the President’s narrative choice. Our earlier work describes the process of governmental “enemy construction,” by which officials use war rhetoric and other signaling behaviors to convey that a person or institution is not merely an institution that, although wholly legitimate, has engaged in behaviors that are disappointing or disapproved, but instead an illegitimate “enemy” triggering a state of Schmittian exceptionalism and justifying the compromise of ordinarily recognized liberties. The Trump administration, with a rhetoric that began during the campaign and burgeoned in the earliest days of Donald Trump’s presidency, has engaged in enemy construction of the press, and the risks that accompany that categorization are grave. This article examines the fuller components of that enemy construction, beyond the overt use of the label. It offers insights into the social, technological, legal, and political realities that make the press ripe for enemy construction in a way that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. It then explores the potential motivations for and consequences of enemy construction. We argue that enemy construction is particularly alarming when the press, rather than some other entity, is the constructed enemy. Undercutting the watchdog, educator, and proxy functions of the press through enemy construction leaves the administration more capable of delegitimizing other institutions and constructing other enemies—including the judiciary, the intelligence community, immigrants, and members of certain races or religions—because the viability and traction of counter-narrative is so greatly diminished. -

Court Green Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2015 Court Green: Dossier: On the Occasion Of Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: On the Occasion Of" (2015). Court Green. 12. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Read good poetry!” —William Carlos Williams COURT GREEN 12 COURT 12 EDITORS CM Burroughs and Tony Trigilio MANAGING EDITOR Cora Jacobs SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jacob Victorine EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Cameron Decker, Patti Pangborn, Taylor Pedersen, and Andre Price Court Green is published annually in association with Columbia College Chicago, Department of Creative Writing. Our thanks to Matthew Shenoda, Interim Chair, Department of Creative Writing; Suzanne Blum-Malley, Interim Dean, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Stanley T. Wearden, Provost; and Kwang-Wu Kim, President and CEO of Columbia College Chicago. Court Green was founded in 2004 by Arielle Greenberg, Tony Trigilio, and David Trinidad. Acknowledgments for this issue can be found on page 209. Court Green is distributed by Ingram Periodicals and Media Solutions. Copyright © 2015 by Columbia College Chicago. ISSN 1548-5242. Magazine cover design by Hannah Rebernick, Columbia College Chicago Creative Services. -

National Geographic Winter 2021

WINTER 2021 TITLES (MARCH - APRIL) National Geographic Winter 2021 - PAGE 1 Cosmic Queries StarTalk's Guide to Who We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We're Going Neil DeGrasse Tyson, James Trefil Key Selling Points STAR AUTHOR WITH HUGE REACH: Neil deGrasse Tyson is the nation's leading astrophysicist, with multiple New York Times bestsellers to his name. He frequently appears on major news networks and pop-culture offerings like The Daily Show, Late Night with Stephen Colbert, and The Joe Rogan Experience. Tyson was named one of Time magazine's 100 Most Influential Persons in the World in 2007. His personal Twitter has a following of 13.9 million, and his tweets frequently make headline news. STRONG PRESS POTENTIAL: The StarTalk brand has its own celebrity power, with a combined social media following of nearly 720,000. The powerhouse podcast, along with Tyson's A-list national television contacts, will lend enormous support to this title. STRONG CROSS PLATFORM SUPPORT: The book's content provides plenty of cutting-edge material for editorial features in National Geographic magazine and National Geographic 9781426221774 National Geographic digital. 1426221770 Pub Date: 3/2/2021 SEQUEL TO TOP-SELLING TITLE: This is a follow-up to StarTalk, NG's successful first $30.00/$38.00 Can. entry with Neil deGrasse Tyson, which has netted 86k for all editions, as well as more Hardcover than 100,000 copies of a YA version sold through Scholastic. 312 Pages Carton Qty: 20 Print Run: 150K Ages 12 And Up, Grades 7 to 17 Summary Science / Physics Catalog Copy: SCI005000 For science geeks, space and physics nerds, and all who want to understand their place in the universe, this enlightening new book from Neil deGrasse Tyson offers a unique take on the mysteries and curiosities of the cosmos, building on rich material from his beloved StarTalk podcast.