Basics of Ocean Circulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report No. 21

Technical Report No. 21 Climatology of the HOPE-G Global Ocean - Sea Ice General Circulation Model Stephanie Legutke, Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum Ernst Maier-Reimer, Max-Planck-Institut für Meteorologie Bundesstraße 55, D-20146 Hamburg Edited by: Modellberatungsgruppe, DKRZ Hamburg, December 1999 ISSN 0940-9327 ABSTRACT The HOPE-G global ocean general circulation model (OGCM) climatology, obtained in a long-term forced integration is described. HOPE-G is a primitive-equation z-level ocean model which contains a dynamic-thermodynamic sea-ice model. It is formulated on a 2.8o grid with increased resolution in low latitudes in order to better resolve equatorial dynamics. The vertical resolution is 20 layers. The purpose of the integration was both to investigate the models ability to reproduce the observed gen- eral circulation of the world ocean and to obtain an initial state for coupled atmosphere - ocean - sea-ice climate simulations. The model was driven with daily mean data of a 15-year integration of the atmo- sphere general circulation model ECHAM4, the atmospheric component in later coupled runs. Thereby, a maximum of the flux variability that is expected to appear in coupled simulations is included already in the ocean spin-up experiment described here. The model was run for more than 2000 years until a quasi-steady state was achieved. It reproduces the major current systems and the main features of the so-called conveyor belt circulation. The observed distribution of water masses is reproduced reasonably well, although with a saline bias in the intermediate water masses and a warm bias in the deep and bottom water of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. -

A Global Ocean Wind Stress Climatology Based on Ecmwf Analyses

NCAR/TN-338+STR NCAR TECHNICAL NOTE - August 1989 A GLOBAL OCEAN WIND STRESS CLIMATOLOGY BASED ON ECMWF ANALYSES KEVIN E. TRENBERTH JERRY G. OLSON WILLIAM G. LARGE T (ANNUAL) 90N 60N 30N 0 30S 60S 90S- 0 30E 60E 90E 120E 150E 180 150 120N 90 6W 30W 0 CLIMATE AND GLOBAL DYNAMICS DIVISION I NATIONAL CENTER FOR ATMOSPHERIC RESEARCH BOULDER. COLORADO I Table of Contents Preface . v Acknowledgments . .. v 1. Introduction . 1 2. D ata . .. 6 3. The drag coefficient . .... 8 4. Mean annual cycle . 13 4.1 Monthly mean wind stress . .13 4.2 Monthly mean wind stress curl . 18 4.3 Sverdrup transports . 23 4.4 Results in tropics . 30 5. Comparisons with Hellerman and Rosenstein . 34 5.1 Differences in wind stress . 34 5.2 Changes in the atmospheric circulation . 47 6. Interannual variations . 55 7. Conclusions ....................... 68 References . 70 Appendix I ECMWF surface winds .... 75 Appendix II Curl of the wind stress . 81 Appendix III Stability fields . 83 iii Preface Computations of the surface wind stress over the global oceans have been made using surface winds from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) for seven years. The drag coefficient is a function of wind speed and atmospheric stability, and the density is computed for each observation. Seven year climatologies of wind stress, wind stress curl and Sverdrup transport are computed and compared with those of other studies. The interannual variability of these quantities over the seven years is presented. Results for the long term and individual monthly means are archived and available at NCAR. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Lecture Notes in Physical Oceanography

LECTURE NOTES IN PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY ODD HENRIK SÆLEN EYVIND AAS 1976 2012 CONTENTS FOREWORD INTRODUCTION 1 EXTENT OF THE OCEANS AND THEIR DIVISIONS 1.1 Distribution of Water and Land..........................................................................1 1.2 Depth Measurements............................................................................................3 1.3 General Features of the Ocean Floor..................................................................5 2 CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF SEAWATER 2.1 Chemical Composition..........................................................................................1 2.2 Gases in Seawater..................................................................................................4 3 PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF SEAWATER 3.1 Density and Freezing Point...................................................................................1 3.2 Temperature..........................................................................................................3 3.3 Compressibility......................................................................................................5 3.4 Specific and Latent Heats.....................................................................................5 3.5 Light in the Sea......................................................................................................6 3.6 Sound in the Sea..................................................................................................11 4 INFLUENCE OF ATMOSPHERE ON THE SEA 4.1 Major Wind -

Navier-Stokes Equation

,90HWHRURORJLFDO'\QDPLFV ,9 ,QWURGXFWLRQ ,9)RUFHV DQG HTXDWLRQ RI PRWLRQV ,9$WPRVSKHULFFLUFXODWLRQ IV/1 ,90HWHRURORJLFDO'\QDPLFV ,9 ,QWURGXFWLRQ ,9)RUFHV DQG HTXDWLRQ RI PRWLRQV ,9$WPRVSKHULFFLUFXODWLRQ IV/2 Dynamics: Introduction ,9,QWURGXFWLRQ y GHILQLWLRQ RI G\QDPLFDOPHWHRURORJ\ ÎUHVHDUFK RQ WKH QDWXUHDQGFDXVHRI DWPRVSKHULFPRWLRQV y WZRILHOGV ÎNLQHPDWLFV Ö VWXG\ RQQDWXUHDQG SKHQRPHQD RIDLU PRWLRQ ÎG\QDPLFV Ö VWXG\ RI FDXVHV RIDLU PRWLRQV :HZLOOPDLQO\FRQFHQWUDWH RQ WKH VHFRQG SDUW G\QDPLFV IV/3 Pressure gradient force ,9)RUFHV DQG HTXDWLRQ RI PRWLRQ K KKdv y 1HZWRQµVODZ FFm==⋅∑ i i dt y )ROORZLQJDWPRVSKHULFIRUFHVDUHLPSRUWDQW ÎSUHVVXUHJUDGLHQWIRUFH 3*) ÎJUDYLW\ IRUFH ÎIULFWLRQ Î&RULROLV IRUFH IV/4 Pressure gradient force ,93UHVVXUHJUDGLHQWIRUFH y 3UHVVXUH IRUFHDUHD y )RUFHIURPOHIW =⋅ ⋅ Fpdydzleft ∂p F=− p + dx dy ⋅ dz right ∂x ∂∂pp y VXP RI IRUFHV FFF= + =−⋅⋅⋅=−⋅ dxdydzdV pleftrightx ∂∂xx ∂∂ y )RUFHSHUXQLWPDVV −⋅pdV =−⋅1 p ∂∂ρ xdmm x ρ = m m V K 11K y *HQHUDO f=− ∇ p =− ⋅ grad p p ρ ρ mm 1RWHXQLWLV 1NJ IV/5 Pressure gradient force ,93UHVVXUHJUDGLHQWIRUFH FRQWLQXHG K 11K f=− ∇ p =− ⋅ grad p p ρ ρ mm K K ∇p y SUHVVXUHJUDGLHQWIRUFHDFWVÄGRZQKLOO³RI WKHSUHVVXUHJUDGLHQW y ZLQG IRUPHGIURPSUHVVXUHJUDGLHQWIRUFHLVFDOOHG(XOHULDQ ZLQG y WKLV W\SH RI ZLQGVDUHIRXQG ÎDW WKHHTXDWRU QR &RULROLVIRUFH ÎVPDOOVFDOH WKHUPDO FLUFXODWLRQ NP IV/6 Thermal circulation ,93UHVVXUHJUDGLHQWIRUFH FRQWLQXHG y7KHUPDOFLUFXODWLRQLVFDXVHGE\DKRUL]RQWDOWHPSHUDWXUHJUDGLHQW Î([DPSOHV RYHQ ZDUP DQG ZLQGRZ FROG RSHQILHOG ZDUP DQG IRUUHVW FROG FROGODNH DQGZDUPVKRUH XUEDQUHJLRQ -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

Vorticity Production Through Rotation, Shear, and Baroclinicity

A&A 528, A145 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015661 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Vorticity production through rotation, shear, and baroclinicity F. Del Sordo1,2 and A. Brandenburg1,2 1 Nordita, AlbaNova University Center, Roslagstullsbacken 23, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Astronomy, AlbaNova University Center, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden Received 31 August 2010 / Accepted 14 February 2011 ABSTRACT Context. In the absence of rotation and shear, and under the assumption of constant temperature or specific entropy, purely potential forcing by localized expansion waves is known to produce irrotational flows that have no vorticity. Aims. Here we study the production of vorticity under idealized conditions when there is rotation, shear, or baroclinicity, to address the problem of vorticity generation in the interstellar medium in a systematic fashion. Methods. We use three-dimensional periodic box numerical simulations to investigate the various effects in isolation. Results. We find that for slow rotation, vorticity production in an isothermal gas is small in the sense that the ratio of the root-mean- square values of vorticity and velocity is small compared with the wavenumber of the energy-carrying motions. For Coriolis numbers above a certain level, vorticity production saturates at a value where the aforementioned ratio becomes comparable with the wavenum- ber of the energy-carrying motions. Shear also raises the vorticity production, but no saturation is found. When the assumption of isothermality is dropped, there is significant vorticity production by the baroclinic term once the turbulence becomes supersonic. In galaxies, shear and rotation are estimated to be insufficient to produce significant amounts of vorticity, leaving therefore only the baroclinic term as the most favorable candidate. -

Assessment of DUACS Sentinel-3A Altimetry Data in the Coastal Band of the European Seas: Comparison with Tide Gauge Measurements

remote sensing Article Assessment of DUACS Sentinel-3A Altimetry Data in the Coastal Band of the European Seas: Comparison with Tide Gauge Measurements Antonio Sánchez-Román 1,* , Ananda Pascual 1, Marie-Isabelle Pujol 2, Guillaume Taburet 2, Marta Marcos 1,3 and Yannice Faugère 2 1 Instituto Mediterráneo de Estudios Avanzados, C/Miquel Marquès, 21, 07190 Esporles, Spain; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (M.M.) 2 Collecte Localisation Satellites, Parc Technologique du Canal, 8-10 rue Hermès, 31520 Ramonville-Saint-Agne, France; [email protected] (M.-I.P.); [email protected] (G.T.); [email protected] (Y.F.) 3 Departament de Física, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Cra. de Valldemossa, km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-971-61-0906 Received: 26 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The quality of the Data Unification and Altimeter Combination System (DUACS) Sentinel-3A altimeter data in the coastal area of the European seas is investigated through a comparison with in situ tide gauge measurements. The comparison was also conducted using altimetry data from Jason-3 for inter-comparison purposes. We found that Sentinel-3A improved the root mean square differences (RMSD) by 13% with respect to the Jason-3 mission. In addition, the variance in the differences between the two datasets was reduced by 25%. To explain the improved capture of Sea Level Anomaly by Sentinel-3A in the coastal band, the impact of the measurement noise on the synthetic aperture radar altimeter, the distance to the coast, and Long Wave Error correction applied on altimetry data were checked. -

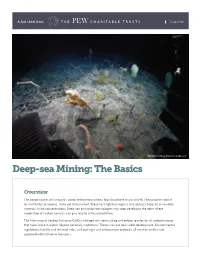

Deep-Sea Mining: the Basics

A fact sheet from June 2018 NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research Deep-sea Mining: The Basics Overview The deepest parts of the world’s ocean feature ecosystems found nowhere else on Earth. They provide habitat for multitudes of species, many yet to be named. These vast, lightless regions also possess deposits of valuable minerals in rich concentrations. Deep-sea extraction technologies may soon develop to the point where exploration of seabed minerals can give way to active exploitation. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is charged with formulating and enforcing rules for all seabed mining that takes place in waters beyond national jurisdictions. These rules are now under development. Environmental regulations, liability and financial rules, and oversight and enforcement protocols all must be written and approved within three to five years. Figure 1 Types of Deep-sea Mining Production support vessel Return pipe Riser pipe Cobalt Seafloor massive Polymetallic crusts sulfides nodules Subsurface plumes 800-2,500 from return water meters deep Deposition 1,000-4,000 meters deep 4,000-6,500 meters deep Cobalt-rich Localized plumes Seabed pump Ferromanganeseferromanganese from cutting crusts Seafloor production tool Nodule deposit Massive sulfide deposit Sediment Source: New Zealand Environment Guide © 2018 The Pew Charitable Trusts 2 The legal foundations • The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Also known as the Law of the Sea Treaty, UNCLOS is the constitutional document governing mineral exploitation on the roughly 60 percent of the world seabed that lies beyond national jurisdictions. UNCLOS took effect in 1994 upon passage of key enabling amendments designed to spur commercial mining. -

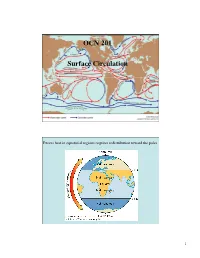

Surface Circulation2016

OCN 201 Surface Circulation Excess heat in equatorial regions requires redistribution toward the poles 1 In the Northern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the right In the Southern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the left Combination of atmospheric cells and Coriolis force yield the wind belts Wind belts drive ocean circulation 2 Surface circulation is one of the main transporters of “excess” heat from the tropics to northern latitudes Gulf Stream http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/Images/gulf_stream_modis_lrg.gif 3 How fast ( in miles per hour) do you think western boundary currents like the Gulf Stream are? A 1 B 2 C 4 D 8 E More! 4 mph = C Path of ocean currents affects agriculture and habitability of regions ~62 ˚N Mean Jan Faeroe temp 40 ˚F Islands ~61˚N Mean Jan Anchorage temp 13˚F Alaska 4 Average surface water temperature (N hemisphere winter) Surface currents are driven by winds, not thermohaline processes 5 Surface currents are shallow, in the upper few hundred metres of the ocean Clockwise gyres in North Atlantic and North Pacific Anti-clockwise gyres in South Atlantic and South Pacific How long do you think it takes for a trip around the North Pacific gyre? A 6 months B 1 year C 10 years D 20 years E 50 years D= ~ 20 years 6 Maximum in surface water salinity shows the gyres excess evaporation over precipitation results in higher surface water salinity Gyres are underneath, and driven by, the bands of Trade Winds and Westerlies 7 Which wind belt is Hawaii in? A Westerlies B Trade -

Impacts of Climate Change on the Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms

Office of Water EPA 820-S-13-001 MC 4304T May 2013 Impacts of Climate Change on the Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms Summary Background Climate change is predicted to change many Algae occur naturally in marine and fresh waters. environmental conditions that could affect the Under favorable conditions that include adequate natural properties of fresh and marine waters both in light availability, warm waters, and high nutrient the US and worldwide. Changes in these factors levels, algae can rapidly grow and multiply causing could favor the growth of harmful algal blooms and “blooms.” Blooms of algae can cause damage to habitat changes such that marine HABs can invade aquatic environments by blocking sunlight and and occur in freshwater. An increase in the depleting oxygen required by other aquatic occurrence and intensity of harmful algal blooms organisms, restricting their growth and survival. may negatively impact the environment, human Some species of algae, including golden and red health, and the economy for communities across the algae and certain types of cyanobacteria, can produce US and around the world. The purpose of this fact potent toxins that can cause adverse health effects to sheet is to provide climate change researchers and wildlife and humans, such as damage to the liver and decision–makers a summary of the potential impacts nervous system. When algal blooms impair aquatic of climate change on harmful algal blooms in ecosystems or have the potential to affect human freshwater and marine ecosystems. Although much health, they are known as harmful algal blooms of the evidence presented in this fact sheet suggests (HABs). -

Ocean and Climate

Ocean currents II Wind-water interaction and drag forces Ekman transport, circular and geostrophic flow General ocean flow pattern Wind-Water surface interaction Water motion at the surface of the ocean (mixed layer) is driven by wind effects. Friction causes drag effects on the water, transferring momentum from the atmospheric winds to the ocean surface water. The drag force Wind generates vertical and horizontal motion in the water, triggering convective motion, causing turbulent mixing down to about 100m depth, which defines the isothermal mixed layer. The drag force FD on the water depends on wind velocity v: 2 FD CD Aa v CD drag coefficient dimensionless factor for wind water interaction CD 0.002, A cross sectional area depending on surface roughness, and particularly the emergence of waves! Katsushika Hokusai: The Great Wave off Kanagawa The Beaufort Scale is an empirical measure describing wind speed based on the observed sea conditions (1 knot = 0.514 m/s = 1.85 km/h)! For land and city people Bft 6 Bft 7 Bft 8 Bft 9 Bft 10 Bft 11 Bft 12 m Conversion from scale to wind velocity: v 0.836 B3/ 2 s A strong breeze of B=6 corresponds to wind speed of v=39 to 49 km/h at which long waves begin to form and white foam crests become frequent. The drag force can be calculated to: kg km m F C A v2 1200 v 45 12.5 C 0.001 D D a a m3 h s D 2 kg 2 m 2 FD 0.0011200 Am 12.5 187.5 A N or FD A 187.5 N m m3 s For a strong gale (B=12), v=35 m/s, the drag stress on the water will be: 2 kg m 2 FD / A 0.00251200 35 3675 N m m3 s kg m 1200 v 35 C 0.0025 a m3 s D Ekman transport The frictional drag force of wind with velocity v or wind stress x generating a water velocity u, is balanced by the Coriolis force, but drag decreases with depth z.