Cooperation Or Co-Optation? Prospects for Democratization in Belarus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testimony :: Stephen Nix

Testimony :: Stephen Nix Regional Program Director, Eurasia - International Republican Institute Mr. Chairman, I wish to thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Commission today. We are on the eve of a presidential election in Belarus which holds vital importance for the people of Belarus. The government of the Republic of Belarus has the inherit mandate to hold elections which will ultimately voice the will of its people. Sadly, the government of Belarus has a track record of denying this responsibility to its people, its constitution, and the international community. Today, the citizens of Belarus are facing a nominal election in which their inherit right to choose their future will not be granted. The future of democracy in Belarus is of strategic importance; not only to its people, but to the success of the longevity of democracy in all the former Soviet republics. As we have witnessed in Georgia and Ukraine, it is inevitable that the time will come when the people stand up and demand their rightful place among their fellow citizens of democratic nations. How many more people must be imprisoned or fined or crushed before this time comes in Belarus? Mr. Chairman, the situation in Belarus is dire, but the beacon of hope in Belarus is shining. In the midst of repeated human rights violations and continual repression of freedoms, a coalition of pro-democratic activists has emerged and united to offer a voice for the oppressed. The courage, unselfishness and determination of this coalition are truly admirable. It is vitally important that the United States and Europe remain committed to their support of this democratic coalition; not only in the run up to the election, but post-election as well. -

The Year in Elections, 2013: the World's Flawed and Failed Contests

The Year in Elections, 2013: The World's Flawed and Failed Contests The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Norris, Pippa, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martinez i Coma. 2014. The Year in Elections 2013: The World's Flawed and Failed Contests. The Electoral Integrity Project. Published Version http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11744445 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA THE YEAR IN ELECTIONS, 2013 THE WORLD’S FLAWED AND FAILED CONTESTS Pippa Norris, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martínez i Coma February 2014 THE YEAR IN ELECTIONS, 2013 WWW. ELECTORALINTEGRITYPROJECT.COM The Electoral Integrity Project Department of Government and International Relations Merewether Building, HO4 University of Sydney, NSW 2006 Phone: +61(2) 9351 6041 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com Copyright © Pippa Norris, Ferran Martínez i Coma, and Richard W. Frank 2014. All rights reserved. Photo credits Cover photo: ‘Ballot for national election.’ by Daniel Littlewood, http://www.flickr.com/photos/daniellittlewood/413339945. Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. Page 6 and 18: ‘Ballot sections are separated for counting.’ by Brittany Danisch, http://www.flickr.com/photos/bdanisch/6084970163/ Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. Page 8: ‘Women in Pakistan wait to vote’ by DFID - UK Department for International Development, http://www.flickr.com/photos/dfid/8735821208/ Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. -

The Mediation of the Concept of Civil Society in the Belarusian Press (1991-2010)

THE MEDIATION OF THE CONCEPT OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN THE BELARUSIAN PRESS (1991-2010) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 IRYNA CLARK School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures ............................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 7 Declaration ....................................................................................................................... 8 Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................ 8 A Note on Transliteration and Translation .................................................................... 9 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 10 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 11 Research objectives and questions ................................................................................... 12 Outline of the Belarusian media landscape and primary sources ...................................... 17 The evolution of the concept of civil society -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Review-Chronicle of Human Violations in Belarus in 2009

The Human Rights Center Viasna Review-Chronicle of Human Violations in Belarus in 2009 Minsk 2010 Contents A year of disappointed hopes ................................................................7 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in January 2009....................................................................9 Freedom to peaceful assemblies .................................................................................10 Activities of security services .....................................................................................11 Freedom of association ...............................................................................................12 Freedom of information ..............................................................................................13 Harassment of civil and political activists ..................................................................14 Politically motivated criminal cases ...........................................................................14 Freedom of conscience ...............................................................................................15 Prisoners’ rights ..........................................................................................................16 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in February 2009................................................................17 Politically motivated criminal cases ...........................................................................19 Harassment of -

Human Rights for Musicians Freemuse

HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship Freemuse is an international organisation advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. OUR MAIN OBJECTIVES ARE TO: • Document violations • Inform media and the public • Describe the mechanisms of censorship • Support censored musicians and composers • Develop a global support network FREEMUSE Freemuse Tel: +45 33 32 10 27 Nytorv 17, 3rd floor Fax: +45 33 32 10 45 DK-1450 Copenhagen K Denmark [email protected] www.freemuse.org HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS Ten Years with Freemuse Human Rights for Musicians: Ten Years with Freemuse Edited by Krister Malm ISBN 978-87-988163-2-4 Published by Freemuse, Nytorv 17, 1450 Copenhagen, Denmark www.freemuse.org Printed by Handy-Print, Denmark © Freemuse, 2008 Layout by Kristina Funkeson Photos courtesy of Anna Schori (p. 26), Ole Reitov (p. 28 & p. 64), Andy Rice (p. 32), Marie Korpe (p. 40) & Mik Aidt (p. 66). The remaining photos are artist press photos. Proofreading by Julian Isherwood Supervision of production by Marie Korpe All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Human rights for musicians – The Freemuse story Marie Korpe 9 Ten years of Freemuse – A view from the chair Martin Cloonan 13 PART I Impressions & Descriptions Deeyah 21 Marcel Khalife 25 Roger Lucey 27 Ferhat Tunç 29 Farhad Darya 31 Gorki Aguila 33 Mahsa Vahdat 35 Stephan Said 37 Salman Ahmad 41 PART II Interactions & Reactions Introducing Freemuse Krister Malm 45 The organisation that was missing Morten -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

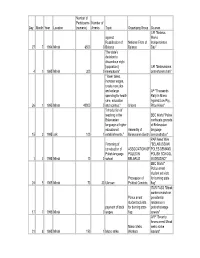

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in November 2009 in Belarus November Started with the Population's Pani

Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in November 2009 In Belarus November started with the population’s panic caused by the epidemic of an acute virus disease that often brought such complication as pneumonia. Though the World Health Organization declared a swine influenza pandemic, on 1 November the deputy minister of health Valiantsina Kachan stated that there was no swine flu in Belarus, irrespective of the fact that tests for swine flu were carried out only in severe cases or after the death of patients. Everybody was well aware that one could die of pneumonia and the medical institutions were overcrowded. However, there was no information about the number of deaths and hospitalizations in Belarus, as the Belarusian officials kept silence. For several day the people bought up all antivirus medicines, masks, etc. Only on 6 November, after an avalanche of alarming news in independent media and internet, the authorities announced holding additional anti-epidemic actions in Minsk and closed educational establishments for quarantine. On the other hand, on 4 November the first deputy minister of information Liliya Ananich stated the ministry ‘will stop any attempts to misinform the population of the country’. The same day Valiantsina Kachan voiced the data from which it followed that 19 people died of pneumonia during the two last weeks. All of them were tested for swine flu and in seven cases the tests were positive. This was all official information. Meanwhile, for 2-29 November 170 819 cases of swine flu and acute respiratory viral infection were registered in Homel oblast alone. -

General Conclusions and Basic Tendencies 1. System of Human Rights Violations

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND BASIC TENDENCIES 1. SYSTEM OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS The year 2003 was marked by deterioration of the human rights situation in Belarus. While the general human rights situation in the country did not improve, in its certain spheres it significantly changed for the worse. Disrespect for and regular violations of the basic constitutional civic rights became an unavoidable and permanent factor of the Belarusian reality. In 2003 the Belarusian authorities did not even hide their intention to maximally limit the freedom of speech, freedom of association, religious freedom, and human rights in general. These intentions of the ruling regime were declared publicly. It was a conscious and open choice of the state bodies constituting one of the strategic elements of their policy. This political process became most visible in formation and forced intrusion of state ideology upon the citizens. Even leaving aside the question of the ideology contents, the very existence of an ideology, compulsory for all citizens of the country, imposed through propaganda media and educational establishments, and fraught with punitive sanctions for any deviation from it, is a phenomenon, incompatible with the fundamental human right to have a personal opinion. Thus, the state policy of the ruling government aims to create ideological grounds for consistent undermining of civic freedoms in Belarus. The new ideology is introduced despite the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus which puts a direct ban on that. -

Review–Chronicle

REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 Human Rights Center Viasna ReviewChronicle » of the Human Rights Violations in Belarus in 2005 VIASNA « Human Rights Center Minsk 2006 1 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 » VIASNA « Human Rights Center 2 Human Rights Center Viasna, 2006 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 INTRODUCTION: main trends and generalizations The year of 2005 was marked by a considerable aggravation of the general situation in the field of human rights in Belarus. It was not only political rights » that were violated but social, economic and cultural rights as well. These viola- tions are constant and conditioned by the authoritys voluntary policy, with Lu- kashenka at its head. At the same time, human rights violations are not merely VIASNA a side-effect of the authoritarian state control; they are deliberately used as a « means of eradicating political opponents and creating an atmosphere of intimi- dation in the society. The negative dynamics is characterized by the growth of the number of victims of human rights violations and discrimination. Under these circums- tances, with a high level of latent violations and concealed facts, with great obstacles to human rights activity and overall fear in the society, the growth points to drastic stiffening of the regimes methods. Apart from the growing number of registered violations, one should men- Human Rights Center tion the increase of their new forms, caused in most cases by the development of the state oppressive machine, the expansion of legal restrictions and ad- ministrative control over social life and individuals. -

NGO Sustainability Index USAID

2009 NGO SUSTAINABILITY INDEX for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia 13th Edition – June 2010 Cover Photo: Volunteers work to preserve the Lietava castle in Slovakia during the project Naša Žilina (Our Žilina), an effort to which nearly 200 corporate volunteers contributed. Photo Credit: Pontis Foundation The 2009 NGO Sustainability Index for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia Developed by: United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Europe and Eurasia Office of Democracy, Governance and Social Transition 2009 NGO SUSTAINABILITY INDEX SCORES COUNTRY Legal Service Viability Capacity Financial Financial Provision Advocacy Environment Public Image Overall Score Infrastructure Organizational Organizational NORTHERN TIER Czech Republic 3.0 3.0 3.1 2.3 2.3 2.8 2.5 2.7 Estonia 1.7 2.3 2.4 1.8 2.3 1.6 1.9 2.0 Hungary 1.7 3.0 3.6 3.1 2.6 2.2 3.3 2.8 Latvia 2.4 3.0 3.3 2.2 2.5 2.4 3.3 2.7 Lithuania 2.2 2.9 3.0 2.1 3.5 3.0 2.9 2.8 Poland 2.2 2.6 2.7 1.8 2.2 1.7 2.2 2.2 Slovakia 2.8 3.0 3.3 2.6 2.5 2.3 2.4 2.7 Slovenia 3.5 3.9 4.4 3.8 3.5 3.7 3.8 3.8 Average 2.4 3.0 3.2 2.5 2.7 2.5 2.8 2.7 SOUTHERN TIER Albania 3.8 3.9 4.6 3.4 3.7 4 3.8 3.9 Bosnia 3.4 3.4 4.8 3.1 4 3.9 3.3 3.7 Bulgaria 2.0 4.3 4.4 2.6 3.2 3.1 3.0 3.2 Croatia 2.8 3 4.1 3.2 3.1 2.7 2.9 3.1 Kosovo 3.5 3.7 4.8 3.8 3.9 3.6 3.7 3.9 Macedonia 3.2 3.7 4.5 3.2 3.8 3.2 3.9 3.6 Montenegro 3.6 4.4 4.9 3.5 4.0 3.9 4.4 4.1 Romania 3.5 3.5 4.2 3.4 3.1 3.2 3.7 3.5 Serbia 4.4 4.2 5.3 3.8 4.3 3.7 4.6 4.3 Average 3.4 3.8 4.6 3.3 3.7 3.5 3.7 3.7 EURASIA: Russia, West NIS, and -

March 2019 Newsnet

NewsNet News of the Association for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies March 2019 v. 59, n. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Magnitsky Act - Behind the 3 Scenes: An interview with the film director, Andrei Nekrasov Losing Pravda, An Interview with 8 Natalia Roudakova Recent Preservation Projects 12 from the Slavic and East European Materials Project The Prozhito Web Archive of 14 Diaries: A Resource for Digital Humanists 17 Affiliate Group News 18 Publications ASEEES Prizes Call for 23 Submissions 28 In Memoriam 29 Personages 30 Institutional Member News Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) 203C Bellefield Hall, 315 S. Bellefield Ave Pittsburgh, PA 15260-6424 tel.: 412-648-9911 • fax: 412-648-9815 www.aseees.org ASEEES Staff Executive Director: Lynda Park 412-648-9788, [email protected] Communications Coordinator: Mary Arnstein 412-648-9809, [email protected] NewsNet Editor & Program Coordinator: Trevor Erlacher 412-648-7403, [email protected] Membership Coordinator: Sean Caulfield 412-648-9911, [email protected] Financial Support: Roxana Palomino 412-648-4049, [email protected] Convention Manager: Margaret Manges 412-648-4049, [email protected] 2019 ASEEES SUMMER CONVENTION 14-16 June 2019 Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb Zagreb, Croatia The 2019 ASEEES Summer Convention theme is “Culture Wars” with a focus on the ways in which individuals or collectives create or construct diametrically opposed ways of understanding their societies and their place in the world. As culture wars intensify across the globe, we invite participants to scrutinize present or past narratives of difference or conflict, and/or negotiating practices within divided societies or across national boundaries.