The River Kelvin; History and Communications in West Central Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

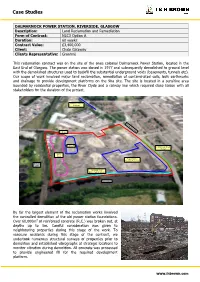

Dalmarnock Power Station, Riverside

Case Studies DALMARNOCK POWER STATION, RIVERSIDE, GLASGOW Description: Land Reclamation and Remediation Form of Contract: NEC3 Option A Duration: 60 weeks Contract Value: £3,400,000 Client: Clyde Gateway Clients Representative: Grontmij This reclamation contract was on the site of the once colossal Dalmarnock Power Station, located in the East End of Glasgow. The power station was closed in 1977 and subsequently demolished to ground level with the demolished structures used to backfill the substantial underground voids (basements, tunnels etc). Our scope of work involved major land reclamation, remediation of contaminated soils, bulk earthworks and drainage to provide development platforms on the 9ha site. The site is located in a sensitive area bounded by residential properties, the River Clyde and a railway line which required close liaison with all stakeholders for the duration of the project. Dalmarnock Road Drainage Crib wall Borrow Pit Dalmarnock Road Tunnel SUDS Pond Power Station Building Footprint Railway Line Perimeter Wall River Clyde Walkway River Clyde By far the largest element of the reclamation works involved the controlled demolition of the old power station foundations. Over 60,000m3 of reinforced concrete (R.C.) was broken out, at depths up to 5m. Careful consideration was given to neighbouring properties during this stage of the work. To reassure residents during this stage of the contract, we undertook numerous structural surveys of properties prior to demolition and established vibrographs at strategic locations to monitor vibration during demolition. All concrete was processed to provide engineered fill for the required development platform. www.ihbrown.com Case Studies The removal of the substantial perimeter wall included a section which ran parallel with the River Clyde Walkway. -

East Dunbartonshire Profile Cite This Report As: Shipton D and Whyte B

East Dunbartonshire Profile Cite this report as: Shipton D and Whyte B. Mental Health in Focus: a profile of mental health and wellbeing in Greater Glasgow & Clyde. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health, 2011. www.GCPH.co.uk/mentalhealthprofiles Acknowledgements Thanks to those who kindly provided data and/or helped with the interpretation: Judith Brown (Scottish Observatory for Work and Health, University of Glasgow), Anna Cameron (Labour Market Statistics, Scottish Government), Jan Cassels (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), Louise Flanagan (NHS Health Scotland), Julie Kidd (ISD Scotland), Stuart King (Scottish Crime & Justice Survey, Scottish Government), Nicolas Krzyzanowski (Scottish Household Survey, Scottish Government), Rebecca Landy (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), Will Linden (Violence Reduction Unit, Strathclyde Police), Carole Morris (ISD Scotland), David McLaren (Scottish House Condition Survey, Scottish Government), Carol McLeod (formally Violence Reduction Unit, Strathclyde Police), Denise Patrick (Labour Market Statistics, Scottish Government), the PsyCIS Steering Group (Mental Health Services, NHS GG&C), Julie Ramsey (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), David Scott (ISD Scotland), Martin Taulbut (NHS Health Scotland), Gordon Thomson (ISD Scotland), Elaine Tod (NHS Health Scotland), Susan Walker (Housing and Household Surveys, The Scottish Government), National Records for Scotland. We would like to also thank the steering group for their invaluable input during the project: Doug -

You May Not Consider a City the Best Place to See Interesting Geology, but Think Again! the City of Glasgow Was, Quite Literally

Glasgow’s Geodiversity K Whitbread1, S Arkley1 and D Craddock2 1British Geological Survey, 2 Glasgow City Council You may not consider a city the best place to see interesting geology, but think again! The city of Glasgow was, quite literally, built on its geology – it may even have been named after one of its rocky features. The geological history of the Glasgow area can be read in the rocks and sediments exposed within the city, from the streams to the buildings and bridges. In 2013 the British Geological Survey Quarrying and building stone conducted a Geodiversity Audit of Sandstones in the Carboniferous sedimentary rocks in the Glasgow the City of Glasgow for Glasgow City area were commonly quarried for Council to identify and describe the building stone. Many former quarries have been infilled, but the best geological features in the city ‘dressed’ faces of worked sandstone, with ‘tool’ marks still area. visible, can be seen in some road cuttings, such as the one below in Here we take you on a tour of some the Upper Limestone Formation at Possil Road. of the sites.... Fossil Forests As well as the local In Carboniferous times, forests of ‘blonde’ sandstone, red Lycopod ‘trees’ grew on a swampy sandstone, granite and river floodplain. In places the stumps other rocks from across of Lycopods, complete with roots, Scotland have been have been preserved. At Fossil Grove, used in many of the a ‘grove’ of fossilised Lycopod stumps historic buildings and was excavated in the Limestone Coal bridges of Glasgow, such Formation during mining. The fossils as in this bridge across were preserved in-situ on their the Kelvin gorge. -

Gilmorehill Campus Development Framework

80 University Brand & Visual issue 1.0 University Brand & Visual issue 1.0 81 of Glasgow Identity Guidelines of Glasgow Identity Guidelines Our lockup (where and how our marque appears) Our primary lockups Our lockup should be used primarily on Background We have two primary lockups, in line with our primary colour front covers, posters and adverts but not Use the University colour palette, and follow palette. We should always use one of these on core publications, within the inside of any document. the colour palette guidelines, to choose the such as: appropriate lockup for your purpose. For For consistency across our material, and · Annual Review example, if the document is for a specific to ensure our branding is clear and instantly · University’s Strategic Plan college, that college’s colour lockup recognisable, we have created our lockup. · Graduation day brochure. is probably the best one to use. If the This is made up of: document is more general, you may want Background to use a lockup from the primary palette. Our marque/Sub-identity Use a solid background colour – or a 70% Help and advice for compiling our transparent background against full bleed approved lockups are available images (see examples on page 84). from Corporate Communications at Our marque [email protected]. Our marque always sits to the left of the lockup on its own or as part of a sub- identity. 200% x U 200% x U Gilmorehill 200% x U Campus Lockup background. Can be solid or used at 70% transparency Development Framework < > contents | print | close -

Stunning Duplex Apartment Overlooking Kelvingrove Park

Stunning duplex apartment overlooking Kelvingrove Park. Park Gardens, Glasgow, G3 Drawing room • Kitchen/dining room • WC • 3 bedrooms including the principal suite • Family bathroom • Utility room • Store room Local Information which features a beautiful Park Gardens, constructed circa staircase and mosaic tiled floor. It 1840, is an historic terrace in the has been fully refurbished to an heart of the popular Park area. exemplary standard. Similar to Edinburgh’s New Town, the area has evolved to be the The main reception rooms are established prime residential situated on the ground level with location of Glasgow. the drawing room to the front of The Park area and the West End the property boasting fine period together make a vibrant hub of features including a fireplace and activity which attracts young cornicing, with beautiful wood professionals and families alike. flooring and large windows Nearby Byres Road and offering an open outlook over Finnieston offer an excellent Kelvingrove Park. The selection of specialist shopping, contemporary kitchen is stunning wine bars and restaurants. and has an excellent range of Kelvingrove Park is overlooked units, high spec integrated from the drawing room, while the appliances and a central Botanic Gardens and Glasgow breakfast island which also University are all within walking houses the induction hob. A large distance. full height window looks over the rear communal garden. There is There is local and private also a modern WC on this level. schooling in the area with Kelvinside Academy, Glasgow A turned staircase with a beautiful Academy, St Aloysius Academy wrought iron balustrade leads and Hillhead Primary all nearby. -

0/2, 59 Raeberry Street, North Kelvinside, Glasgow, G20 6EQ.Indd

0/2, 59 Raeberry Street NORTH KELVINSIDE, GLASGOW, G20 6EQ 0141 404 5474 0/2, 59 Raeberry Street North Kelvinside, Glasgow, G20 6EQ Situated in North Kelvinside, this fl at is in a upgraded electrics and lighting) throughout highly desirable West End location and is with a fresh, contemporary theme. The just a short distance from a fi ne selection of apartment has been successfully and cleverly amenities on Great Western Road and Byres designed to off er contemporary living, within Road, together with the wonderful, nearby this popular development. Off ering bright Botanic Gardens. The property is also close living space, the easily-kept accommodation to Kelvinbridge underground and Glasgow extends to a welcoming entrance hall with University. There are good road links to the a storage recess. Immediately impressive nearby Clyde Tunnel, Clydeside Expressway ‘dual-aspect’ lounge/bedroom area. This and M8 motorway network. zone is open-plan to a well equipped and newly fi tted kitchen, with a good range This beautifully appointed, ground fl oor, of fl oor and wall mounted units and a studio apartment is located within the complementary worktop. It further benefi ts desirable West End of Glasgow, which has from an integrated oven, hob, extractor hood, excellent amenities on its doorstep. The washing machine and fridge/freezer. property off ers fl exible accommodation and its attractive position makes it an ideal choice There is a small dressing room/study area off for a young professional, working in the city the lounge. This allows access (via a sliding or commuting further afi eld. -

Delivery Plan Update March 2017

Delivery Plan Update March 2017 Table of Contents Overview .................................................................................................... 3 1. Delivering for our customers .............................................................. 5 2. Delivering our investment programme ............................................ 10 3. Providing continuous high quality drinking water ......................... 16 4. Protecting and enhancing the environment ................................... 18 5. Supporting Scotland’s economy and communities ....................... 21 6. Financing our services ...................................................................... 24 7. Scottish Water’s Group Plan and Supporting the Hydro Nation .. 33 2 Overview This update to our Delivery Plan is submitted to Scottish Ministers for approval. It highlights those areas where the content of our original Delivery Plan for the 2015-21 period and the update provided in 2016 have been revised. In our 2015 Delivery Plan we stated that we were determined to deliver significant further improvements for our customers and out-perform our commitments. As we conclude the second year of the 2015-21 period we are on-track to achieve this ambition. Key highlights of our progress so far include: We have successfully driven up customer satisfaction and driven down the number of complaints. As a result our Customer Experience score has risen further this year, and is currently at 85.3, well above our Delivery Plan target of 82.6. Since the start of the regulatory -

Twentyci Property & Homemover Report

TwentyCi Property & Homemover Report – Q3 2017 Information embargoed until Wednesday 4th October 2017 at 00:01 Welcome to the latest TwentyCi Property & Homemover Report, a quarterly review of the UK property market. As a life event data company, TwentyCi has exclusive access to more than 29 billion qualified data points across the whole of the property sector – for both property purchases and rental. In addition to tracking sales momentum, this ‘state of the nation’ report provides unique insight into the people behind the numbers, creating a picture of the demographic, regional and socio-economic factors impacting the housing market. With a 99.6% view of both the property sales and rental markets, the TwentyCi Property & Homemover Report is the most comprehensive factual source of home moving data available. Key take-outs for Q3 2017 • Overall the volatile market is starting to stabilise with exchanges up 15.2% year-on-year and house prices increasing by 1.5% for the year. However London experiences lower growth in exchanges than the rest of the UK at 9% year-on-year, and prices drop by 8.4% in the Capital – one of the key reasons behind the overall fall in price for the market. • While the majority of market activity is for properties under £250k and with sub £50k household incomes, the biggest growth in transactions this quarter has been among buyers in higher income bands purchasing higher value properties. • Online-only estate agents’ market share increases by 19% this quarter. All data is based on Q3 2017 versus Q3 2016 year-on-year comparisons unless otherwise stated. -

Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Service Directory 2014 Content Page

Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Service Directory 2014 Content Page About the CHP 1 Glasgow City CHP Headquarters 2 North East Sector 3 North West Sector 4 South Sector 5 Adult Protection 6 Child Protection 6 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 6 Addictions 7 - 9 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 - 12 Children and Families 13 - 14 Dental and Oral Health 15 Diabetes 16 Dietetics 17 Domestic Abuse / Violence 18 Employability 19 - 20 Equality 20 Healthy Living 21 Health Centres 22 - 23 Hospitals 24 - 25 Housing and Homelessness 26 - 27 Learning Disabilities 28 - 29 Mental Health 30 - 40 Money Advice 41 Nursing 41 Physiotherapy 42 Podiatry 42 Respiratory 42 Rehabilitation Services 43 Sexual Health 44 Rape and Sexual Assault 45 Stop Smoking 45 Transport 46 Volunteering 46 Young People 47-49 Public Partnership Forum 50 Comments and Complaints 51-21 About Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Glasgow City Community Health Partnership (GCCHP) was established in November 2010 and provides a wide range of community based health services delivered in homes, health centres, clinics and schools. These include health visiting, health improvement, district nursing, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy, podiatry, nutrition and dietetic services, mental health, addictions and learning disability services. As well as this, we host a range of specialist services including: Specialist Children’s Services, Homeless Services and The Sandyford. We are part of NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde and provide services for 584,000 people - the entire population living within the area defined by the LocalAuthority boundary of Glasgow City Council. Within our boundary, we have: 154 GP practices 136 dental practices 186 pharmacies 85 optometry practices (opticians) The CHP has more than 3,000 staff working for it and is split into three sectors which are aligned to local social work and community planning boundaries. -

Maryhill/Kelvin Area Partnership Multi Member Electoral Ward 15

Area Partnership Profile Maryhill/Kelvin Area Partnership Multi Member Electoral Ward 15 This profile provides comparative information on the Maryhill/Kelvin Area Partnership/ Multi Member Electoral Ward including information on the population; health; labour market; poverty; community safety and public facilities within the area. 1. General Information about the Maryhill/Kelvin Area Partnership 1.1 Maryhill/Kelvin Area Partnership covers the areas of Wyndford, Kelvindale, Gilshochill, Cadder, Summerston and Acre. Housing ranges from traditional sandstone tenements to large housing association estates. The Forth and Clyde Canal runs through the area. It has a mixed population including a large number of students. Map 1: Maryhill Kelvin Area Partnership Table 1: Maryhill/Kelvin Area Partnership - Summary Population (2011 Census) 26,971 (down 2.8%) Population (2011 Census) exc. communal establishments 25,802 Electorate (2012) 22,813 Occupied Households (2011 Census) 13,225 (up 0.7%) Average Household Size (2011) exc. communal establishments 1.95 Housing Stock (2013) 13,654 No. of Dwellings Per Hectare (2012) 20.6 Working Age Population 16-64 (2011 Census) 18,770 (69.6%) Out Of Work Benefit Claimants (May 2013) 3,675 (19.6%) Job Seekers Allowance (Nov 2013) 899 (4.8%) Page 1 of 33 2. Demographic & Socio Economic Information 2.1 At the time of writing, the available 2011 Census Information does not provide all the information included in this section (e.g. household composition). Thus, some information in the profile is based on other information sources which are identified in the report. The profile will be updated as and when further 2011 Census information is available. -

Open Space Strategy Consultative Draft

GLASGOW OPEN SPACE STRATEGY CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Prepared For: GLASGOW CITY COUNCIL Issue No 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Glasgu: The Dear Green Place 11 3. What should open space be used for? 13 4. What is the current open space resource? 23 5. Place Setting for improved economic and community vitality 35 6. Health and wellbeing 59 7. Creating connections 73 8. Ecological Quality 83 9. Enhancing natural processes and generating resources 93 10. Micro‐Climate Control 119 11. Moving towards delivery 123 Strategic Environmental Assessment Interim Environment Report 131 Appendix 144 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 1. Executive Summary The City of Glasgow has a long tradition in the pursuit of a high quality built environment and public realm, continuing to the present day. This strategy represents the next steps in this tradition by setting out how open space should be planned, created, enhanced and managed in order to meet the priorities for Glasgow for the 21st century. This is not just an open space strategy. It is a cross‐cutting vision for delivering a high quality environment that supports economic vitality, improves the health of Glasgow’s residents, provides opportunities for low carbon movement, builds resilience to climate change, supports ecological networks and encourages community cohesion. This is because, when planned well, open space can provide multiple functions that deliver numerous social, economic and environmental benefits. Realising these benefits should be undertaken in a way that is tailored to the needs of the City. As such, this strategy examines the priorities Glasgow has set out and identifies six cross‐cutting strategic priority themes for how open space can contribute to meeting them. -

This Is the Title. It Is Arial 16Pt Bold

Green Flag Award Park Winners 2017 Local Authority Park Name New Aberdeen City Council Duthie Park Aberdeen City Council Hazlehead Park Aberdeen City Council Johnston Gardens Y Aberdeen City Council Seaton Park Aberdeenshire Council Aden Country Park Aberdeenshire Council Haddo Park Dumfries & Galloway Council Dock Park Dundee City Council Barnhill Rock Garden Dundee City Council Baxter Park Trottick Mill Ponds Local Nature Dundee City Council Reserve Dundee City Council Dundee Law Y Dundee City Council Templeton Woods East Renfrewshire Council Rouken Glen Park Edinburgh Braidburn Valley Park Edinburgh Burdiehouse Burn Valley Park Edinburgh Corstorphine Hill Edinburgh Craigmillar Castle Park Edinburgh Easter Craiglockhart Hill Edinburgh Ferniehill Community Park Edinburgh Ferry Glen & Back Braes Edinburgh Figgate Burn Park www.keepscotlandbeautiful.org 1 Edinburgh Hailes Quarry Park Edinburgh Harrison Park Hermitage of Braid inc Blackford Hill Edinburgh & Pond Edinburgh Hopetoun Crescent Gardens Edinburgh Inverleith Park Edinburgh King George V Park, Eyre Place Edinburgh Lochend Park Edinburgh London Road Gardens Edinburgh Morningside Park Edinburgh Muirwood Road Park Edinburgh Pentland Hills Regional Park Edinburgh Portobello Community Garden Edinburgh Prestonfield Park Edinburgh Princes Street Gardens Edinburgh Ravelston Park & Woods Edinburgh Rosefield Park Edinburgh Seven Acre Park Edinburgh Spylaw Park Edinburgh St Margarets Park Edinburgh Starbank Park Edinburgh Station Road Pk, S Queensferry Edinburgh Victoria Park Falkirk Community