The Road from Mont Pèlerin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Removing Obstacles on the Path to Economic Freedom1

Removing Obstacles on the Path to Economic Freedom1 John B. Taylor Mont Pelerin Society Fort Worth, Texas May 22, 2019 My remarks on removing obstacles on the path to economic freedom touch on themes raised at Mont Pelerin Society meetings for many years. But here I emphasize that the obstacles often change their form over time and pop up in surprising ways. I see two basic kinds of obstacles. First are obstacles based on claims that the principle ideas of economic freedom are wrong or do not work. The principle ideas of economic freedom include the rule of law, predictable policies, reliance on markets, attention to incentives, and limitations on government.2 This first kind of obstacle largely promotes the opposite of these principles, arguing that the rule of law should be replaced by arbitrary government actions, that policy predictability is no virtue, that market prices can be replaced by central decrees, that incentives matter little, and that government does not need to be restrained. Many were making such claims at the time that the Mont Pelerin Society was founded in 1947. Communist governments were taking hold. Socialism was creeping up everywhere. “The common objective of those who met at Mont Pelerin was undoubtedly to halt and reverse current political, social, and economic trends toward socialism,” as R. M. Hartwell described the first meeting in his history of the Mont Pelerin Society.3 Despite many successes, these claims have returned today in renewed calls for socialism and criticism of free market capitalism as a way to improved standards of living. -

ANTONY FISHER Champion of Liberty

ANTONY FISHER Champion of Liberty Gerald Frost First published in Great Britain in 2002 by Profile Books Ltd. Copyright: Gerald Frost Condensed in 2008 by David Moller Copyright: Institute of Economic Affairs. Additional material on Dorian Fisher supplied by Linda Whetstone and on the Atlas Economic Research Foundation by John Blundell and Colleen Dyble. 1 Introduction When Antony Fisher died in San Francisco on July 9, 1988, aged 73, four weeks after being knighted in the Queen’s birthday honours list, the world was largely unaware of him or his influence. He was not listed in Who’s Who. He was not well known to the British or American media. He had never held major elected office. Although he had made – and lost – a considerable fortune he relied during his latter years on the financial support of a rich and devoted second wife. The belated knighthood, which fitted the tall, sparse, handsome Englishman like a glove, was almost the sole public recognition he received during his lifetime, and this did not come until he was terminally ill. Only two politicians, Enoch Powell and Keith Joseph, attended his memorial service. That, however, would probably have been more a matter of satisfaction than of regret, since throughout his life the former businessman and decorated World War II pilot displayed an ill-concealed contempt for the generality of politicians. He believed that their capacity for harm far outweighed their ability to do good. Among MPs generally, probably only a handful were aware of Fisher’s remarkable influence. Yet in founding the Institute of Economic Affairs, the London-based free-market think tank, he had played a crucial role in helping to reverse economic trends that many had judged to be irreversible, thereby changing the direction of British post-war politics. -

Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Zora Neale Hurston on War, Race, the State, and Liberty

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Zora Neale Hurston on War, Race, the State, and Liberty ✦ DAVID T. BEITO AND LINDA ROYSTER BEITO he ideals of liberty, individualism, and self-reliance have rarely had more enthusiastic champions than Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Zora TNeale Hurston. All three were out of step with the dominant worldview of their times. They had their peak professional years during the New Deal and World War II, when faith in big government was at high tide. -

The Allais Paradox: What It Became, What It Really Was, What It Now Suggests to Us

Economics and Philosophy (2019), 35, 423–459 doi:10.1017/S0266267118000469 ARTICLE The Allais paradox: what it became, what it really was, what it now suggests to us Philippe Mongin GREGHEC, 1 rue de la Libération, F-78350 Jouy-en-Josas, France Email: [email protected] (Received 11 June 2018; revised 24 August 2018; accepted 27 August 2018; first published online 30 January 2019) Abstract Whereas many others have scrutinized the Allais paradox from a theoretical angle, we study the paradox from an historical perspective and link our findings to a suggestion as to how decision theory could make use of it today. We emphasize that Allais proposed the paradox as anormativeargument, concerned with ‘the rational man’ and not the ‘real man’,touse his words. Moreover, and more subtly, we argue that Allais had an unusual sense of the normative, being concerned not so much with the rationality of choices as with the rationality of the agent as a person. These two claims are buttressed by a detailed investigation – the first of its kind – of the 1952 Paris conference on risk, which set the context for the invention of the paradox, and a detailed reconstruction – also the first of its kind – of Allais’s specific normative argument from his numerous but allusive writings. The paper contrasts these interpretations of what the paradox historically represented, with how it generally came to function within decision theory from the late 1970s onwards: that is, as an empirical refutation of the expected utility hypothesis, and more specifically of the condition of von Neumann–Morgenstern independence that underlies that hypothesis. -

Rousas John Rushdoony: a Brief History, Part V Year-End Sale Martin Selbrede “An Opportunity

Faith for All of Life September/October 2016 Publisher & Chalcedon President Editorials Rev. Mark R. Rushdoony 2 From the President Chalcedon Vice-President Rousas John Rushdoony: A Brief History, Part V Year-End Sale Martin Selbrede “An Opportunity... Thanks Be to God!” 30% OFF Editor 20 From the Founder All orders thru Martin Selbrede 2 Corinthians, Godly Social Order Jan. 31, 2017 Managing Editor The True Perspective (2 Cor. 4:8-18) Susan Burns Features Contributing Editor Lee Duigon 7 Rousas John Rushdoony as Philosopher Jean-Marc Berthoud Chalcedon Founder Rev. R. J. Rushdoony 14 Rushdoony on History (1916-2001) Otto J. Scott was the founder of Chalcedon 17 For Such a Time as This and a leading theologian, church/ state expert, and author of Andrea Schwartz numerous works on the applica- Columns tion of Biblical Law to society. 19 Fragile World Receiving Faith for All of Life: This Movie Reviewed by Lee Duigon magazine will be sent to those who request it. At least once a year we ask 23 The Sleeping Princess of Nulland by Aaron Jagt that you return a response card if you Book Reviewed by Lee Duigon wish to remain on the mailing list. Subscriptions are $20 per year ($35 27 Product Catalog (YEAR-END SALE! Save 30% on all orders for Canada; $45 for International). through January 31, 2017) Checks should be made out to Chalcedon and mailed to P.O. Box 158, Vallecito, CA 95251 USA. Chalcedon may want to contact its readers quickly by means of e-mail. Faith for All of Life, published bi-monthly by Chalcedon, a tax-exempt Christian foundation, is sent to all who If you have an e-mail address, please request it. -

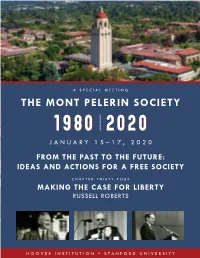

The Mont Pelerin Society

A SPECIAL MEETING THE MONT PELERIN SOCIETY JANUARY 15–17, 2020 FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE: IDEAS AND ACTIONS FOR A FREE SOCIETY CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY RUSSELL ROBERTS HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1 1 MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY Prepared for the January 2020 Mont Pelerin Society Meeting Hoover Institution, Stanford University Russ Roberts John and Jean De Nault Research Fellow Hoover Institution Stanford University [email protected] 1 2 According to many economists and pundits, we are living under the dominion of Milton Friedman’s free market, neoliberal worldview. Such is the claim of the recent book, The Economists’ Hour by Binyamin Applebaum. He blames the policy prescriptions of free- market economists for slower growth, inequality, and declining life expectancy. The most important figure in this seemingly disastrous intellectual revolution? “Milton Friedman, an elfin libertarian…Friedman offered an appealingly simple answer for the nation’s problems: Government should get out of the way.” A similar judgment is delivered in a recent article in the Boston Review by Suresh Naidu, Dani Rodrik, and Gabriel Zucman: Leading economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman were among the founders of the Mont Pelerin Society, the influential group of intellectuals whose advocacy of markets and hostility to government intervention proved highly effective in reshaping the policy landscape after 1980. Deregulation, financialization, dismantling of the welfare state, deinstitutionalization of labor markets, reduction in corporate and progressive taxation, and the pursuit of hyper-globalization—the culprits behind rising inequalities—all seem to be rooted in conventional economic doctrines. -

Maurice Allais on Equilibrium and Capital in Some of His 1940S Writings

QUADERNI DEL DIPARTIMENTO DI ECONOMIA POLITICA E STATISTICA Ariel Dvoskin Maurice Allais on Equilibrium and Capital in some of his 1940s Writings n. 690 – Dicembre 2013 Abstract - The article discusses M. Allais’ contributions on equilibrium and capital during the 1940s. While in his Traité (1943) Allais formalizes for the first time an intertemporal general equilibrium (IGE) in a finite- horizon economy, he subsequently abandons this notion, and in the Économie (1947) resumes, instead, the more traditional method based on the notion of stationary equilibrium. The article argues: i) that Allais’ reasons to leave the IGE framework behind, of which the most important turn round his misgivings about the sufficiently correct foresight entailed by that notion, and that reflect the impossibility to establish a correspondence between observations and theory by means of the IGE method, are well-justified; ii) that his shift to the method based on the notion of stationary equilibrium to connect the results of neoclassical theory with observations cannot be accepted, since a notion of stationary equilibrium that would make this correspondence possible must face an insurmountable difficulty in the treatment of the factor capital. Keywords: Allais, Intertemporal Equilibrium, Stationary Equilibrium, Perfect Foresight, Centre of Gravitation JelClassification: B21-B30- B41-D50-D24 The author is grateful to professors F. Petri, A. Béraud and S. Fratini for their very helpful comments to previous drafts of this article. Thanks are also due to N. Semboloni of the library of the Faculty of Economics, University of Siena. The usual disclaimers apply. Ariel Dvoskin, University of Siena (Italy) and University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). -

Read-I-Pencil.Pdf

There is no better, more easily understood, and more fun explanation of the complexity of markets than Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil.” It ought to give considerable pause when we listen to the arrogance of politicians who tell us they can manage an economy better than millions, perhaps billions, of independent decision makers in pursuit of their own goals. Its message to would-be planners is to bug out! WALTER E. WILLIAMS PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS • GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY “I, Pencil” is a superb case study of free markets in action. Half of the world’s economic problems would vanish if everyone would read “I, Pencil.” BURTON W. FOLSOM PROFESSOR OF HISTORY • HILLSDALE COLLEGE What have economists contributed to human knowledge? Plenty, but the magical, beautiful idea of the division of labor might rank as the most important insight. “I, Pencil” explains we create so much more wealth as a community than we ever could alone - in fact, even the simplest item cannot be made without a complex division of labor. JEFFREY A. TUCKER DIRECTOR OF DIGITAL DEVELOPMENT • FEE “I, Pencil” provides remarkable insights into the complexity generated by market mechanisms. Textbook economics almost never incorporates these insights. MICHAEL STRONG CO-FOUNDER • CONSCIOUS CAPITALISM CEO • RADICAL SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURS FEE’s mission is to inspire, educate, and connect future leaders with the economic, ethical, and legal principles of a free society. Join us online at: FEE.org Facebook.com/FEEonline Twitter.com/FEEonline (@feeonline) Foundation for Economic Education 1819 Peachtree Road NE, Suite 300 Atlanta, Georgia 30309 Telephone: (404) 554-9980 Print ISBN: 978-1-57246-043-0 Ebook ISBN: 978-1-57246-042-3 Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. -

Atlas Network Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80k2f0h No online items Register of the Atlas Network records Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015, 2019 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Atlas Network 2015C50 1 records Title: Atlas Network records Date (inclusive): 1946-2013 Collection Number: 2015C50 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: In English and Spanish Physical Description: 319 ms. boxes, 1 oversize box(160.5 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, memoranda, conference papers and other conference materials, fundraising and grant award records, other financial records, and printed matter relating to international promotion of free market economic policies. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 2015. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Atlas Network records, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Historical Note The Atlas Network was founded in Fairfax, Virginia, as the Atlas Economic Research Foundation, in 1981. Its founder, Sir Antony Fisher (1915-1988), had already created the Institute of Economic Affairs in his native Great Britain and the Fraser Institute in Canada. The purpose of these organizations was promotion of free market economics, limited government, and deregulation and privatization to the greatest extent possible. -

Betting on People the Olin Foundation’S Support for Law and Eco- Nomics Was Part of a Larger Success in Public-Policy Philanthropy

4 Betting on People The Olin Foundation’s support for law and eco- nomics was part of a larger success in public-policy philanthropy. The foundation wanted to build up an alternative intellectual infrastructure that could compete with entrenched academic and media elites at generating new ideas for the governance of American society. “What we desperately need in America today is a powerful counterintelligentsia,” wrote longtime Olin president William Simon in his 1978 bestselling book, A Time for Truth. He wanted 50 to bolster thinkers dedicated to “individual liberty...meritocracy...and the free market.... Such an intelligentsia exists, and an audience awaits its views.” Just about every aspect of the Olin Foundation’s philanthropy involved meeting that long-term goal. It was a monumental challenge. Though much of the funder’s grantmaking focused on scholars at col- leges and universities, today left-wing orthodoxies are even more dom- inant on campuses than when the foundation first started to address this problem in the 1970s. Can we consider Olin to have succeeded in fostering fresh thinking that translates into altered public policies? First, it’s important to note that Olin had a few savvy allies in its cause. The earliest efforts in this area were made by the William Volker Fund way back in the 1940s. In 1947, the Volker Fund agreed to help a group of 17 economists fly from the United States to Switzerland for the first meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, an organization of libertarian economists founded by Friedrich Hayek to promote free markets and refute socialism. -

Neoliberal Reason and Its Forms: Depoliticization Through Economization∗

Neoliberal reason and its forms: Depoliticization through economization∗ Yahya M. Madra Department of Economics Boğaziçi University Bebek, 34342, Istanbul, Turkey [email protected] Yahya M. Madra studied economics in Istanbul and Amherst, Massachusetts. He has taught at the universities of Massachusetts and Boğaziçi, and at Skidmore and Gettysburg Colleges. He currently conducts research in history of modern economics at Boğaziçi University with the support of TÜBITAK-BIDEB Scholarship. His work appeared in Journal of Economic Issues, Rethinking Marxism, The European Journal of History of Economic Thought, Psychoanalysis, Society, Culture and Subjectivity as well as edited volumes. His current research is on the role of subjectivity in political economy of capitalism and post-capitalism. and Fikret Adaman Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University Bebek, 34342, Istanbul, Turkey [email protected] Fikret Adaman studied economics in Istanbul and Manchester. He has been lecturing at Boğaziçi University on political economy, ecological economics and history of economics. His work appeared in Journal of Economic Issues, New Left Review, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Economy and Society, Ecological Economics, The European Journal of History of Economic Thought, Energy Policy and Review of Political Economy as well as edited volumes. His current research is on the political ecology of Turkey. DRAFT: Istanbul, October 3, 2012 ∗ Earlier versions of this paper have been presented in departmental and faculty seminars at Gettysburg College, Uludağ University, Boğaziçi University, İstanbul University, University of Athens, and New School University. The authors would like to thank the participants of those seminars as well as to Jack Amariglio, Michel Callon, Pat Devine, Harald Hagemann, Stavros Ioannides, Ayşe Mumcu, Ceren Özselçuk, Maliha Safri, Euclid Tsakalatos, Yannis Varoufakis, Charles Weise, and Ünal Zenginobuz for their thoughtful comments and suggestions on the various versions of this paper. -

The Essential Von Mises

The Essential von Mises The Essential von Mises Murray N. Rothbard LvMI MISES INSTITUTE Scholar, Creator, Hero © 1988 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute The Essential von Mises first published in 1973 by Bramble Minibooks, Lansing Michigan Copyright © 2009 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute and published under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/ New matter copyright © 2009 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute Ludwig von Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832 Mises.org ISBN: 978-1-933550-41-1 Contents Introduction by Douglas E. French . vii Part One: The Essential von Mises 1. The Austrian School. 3 2. Mises and “Austrian Economics”: The Theory of Money and Credit . .13 3. Mises on the Business Cycle . 21 4. Mises in the Interwar Period . 25 5. Mises on Economic Calculation and Socialism . 29 6. Mises on the Methodology of Economics. 31 7. Mises and Human Action . 35 8. Mises in America . .41 9. The Way Out . 45 Part Two: Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero 1. The Young Scholar . 51 2. The Theory of Money and Credit. 55 3. The Reception of Mises and of Money and Credit . 67 4. Mises in the 1920s: Economic Adviser to the Government . 73 5. Mises in the 1920s: Scholar and Creator . 79 6. Mises in the 1920s: Teacher and Mentor . 91 7. Exile and the New World . 99 8. Coda: Mises the Man . 115 v Introduction he two essays printed in this monograph were written by my Tteacher Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995) about his teacher Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973).