Executive Privilege” 7 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petitioner, V

No. 19-____ In The Supreme Court of the United States ____________________ ROBERT A. PEREZ, Petitioner, v. STATE OF COLORADO, Respondent. ____________________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Colorado ____________________ PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ____________________ Ned R. Jaeckle Jeffrey L. Fisher COLORADO STATE PUBLIC O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP DEFENDER 2765 Sand Hill Road 1300 Broadway, Suite 300 Menlo Park, CA 94025 Denver, CO 80203 Meaghan VerGow Kendall Turner Counsel of Record O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP 1625 Eye Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 383-5204 [email protected] i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether, and to what extent, the Sixth and Four- teenth Amendments guarantee a criminal defendant the right to discover potentially exculpatory mental health records held by a private party, notwithstand- ing a state privilege law to the contrary. i STATEMENT OF RELATED PROCEEDINGS Perez v. People, Colorado Supreme Court No. 19SC587 (Feb. 24, 2020) (available at 2020 WL 897586) (denying Perez’s petition for a writ of certio- rari) People v. Perez, Colorado Court of Appeals No. 16CA1180 (June 13, 2019) (affirming trial court judg- ment) People v. Perez, Colorado District Court No. 14CR4593 (Apr. 7, 2016) (granting motion to quash subpoena seeking mental health records) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED ........................................ i STATEMENT OF RELATED PROCEEDINGS ....... i PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ........... 1 OPINIONS BELOW .................................................. 1 JURISDICTION ........................................................ 1 RELEVANT CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS .................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................. 4 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT................ 8 A. State high courts and federal courts of appeals are openly split on the question presented. -

The President, Congress, and the Courts

The Yale Law Journal Volume 83, Number 6, May 1974 The President, Congress, and the Courts Raoul Bergert I. Subpoenaing the President: Jefferson v. Marshall in the Burr Case We do not think that the President is exalted above legal process .. .and if the President possesses information of any nature which might tend to serve the cause of Aaron Burr, a subpoena should issue to him, notwithstanding his elevated station. Alexander McRae, of counsel for President Jefferson' Chief Justice Marshall's rulings on President Jefferson's claim of right to withhold information in the trial of Aaron Burr have been a source of perennial debate. Eminent writers have drawn demon- strably erroneous deductions from the record. For example, Edward t Charles Warren Senior Fellow in American Legal History, Harvard University Law School. 1. 1 T. CARPENTER, THE TRIAL OF COLONEL AARON BURR 75 (1807). McRae's co-counsel, William Wirt, who served as Attorney General of the United States for twelve consecu- tive years, stated that "if the production of this letter would not compromit [sic] the safety of the United States, and it can be proved to be material to Mr. Burr, he has a right to demand it. Nay, in such a case, I will admit his right to summon the President ... ."Id. at 82. His associate, George Hay, the United States Attorney, stated, I never had the idea of clothing the President . with those attributes of di- vinity. That high officer is but a man; he is but a citizen; and, if he knows anything in any case, civil or criminal, which might affect the life, liberty or property of his fellow-citizens . -

Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate

DePaul Law Review Volume 23 Issue 2 Winter 1974 Article 5 Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate Luis Kutner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Luis Kutner, Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate, 23 DePaul L. Rev. 658 (1974) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol23/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVICE AND DISSENT: DUE PROCESS OF THE SENATE Luis Kutner* The Watergate affair demonstrates the need for a general resurgence of the Senate's proper role in the appointive process. In order to understand the true nature and functioning of this theoretical check on the exercise of unlimited Executive appointment power, the author proceeds through an analysis of the Senate confirmation process. Through a concurrent study of the Senate's constitutionally prescribed function of advice and consent and the historicalprecedent for Senatorial scrutiny in the appointive process, the author graphically describes the scope of this Senatorialpower. Further, the author attempts to place the exercise of the power in perspective, sug- gesting that it is relative to the nature of the position sought, and to the na- ture of the branch of government to be served. In arguing for stricter scrutiny, the author places the Senatorial responsibility for confirmation of Executive appointments on a continuum-the presumption in favor of Ex- ecutive choice is greater when the appointment involves the Executive branch, to be reduced proportionally when the position is either quasi-legis- lative or judicial. -

June 11, 2021 the Honorable Xavier Becerra Secretary Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Ave S.W. Washingto

June 11, 2021 The Honorable Xavier Becerra Secretary Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Ave S.W. Washington, D.C. 20201 The Honorable Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D. Director National Institutes of Health 9000 Rockville Pike Rockville, MD 20892 Dear Secretary Becerra and Director Collins, Pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 2954 we, as members of the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, write to request documents regarding the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recent release of approximately 4,000 pages of NIH email communications and other documents from early 2020 has raised serious questions about NIH’s handling of COVID-19. Between June 1and June 4, 2021, the news media and public interest groups released approximately 4,000 pages of NIH emails and other documents these organizations received pursuant to Freedom of Information Act requests.1 These documents, though heavily redacted, have shed new light on NIH’s awareness of the virus’ origins in the early stages of the COVID- 19 pandemic. In a January 9, 2020 email, Dr. David Morens, Senior Scientific Advisor to Dr. Fauci, emailed Dr. Peter Daszak, President of EcoHealth Alliance, asking for “any inside info on this new coronavirus that isn’t yet in the public domain[.]”2 In a January 27, 2020 reply, Dr. Daszak emailed Dr. Morens, with the subject line: “Wuhan novel coronavirus – NIAID’s role in bat-origin Covs” and stated: 1 See Damian Paletta and Yasmeen Abutaleb, Anthony Fauci’s pandemic emails: -

Nixon Now: the Courts and the Presidency After Twenty-Five Years

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1999 Nixon Now: The ourC ts and the Presidency after Twenty-five Years Michael Stokes Paulsen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Paulsen, Michael Stokes, "Nixon Now: The ourC ts and the Presidency after Twenty-five Years" (1999). Minnesota Law Review. 1969. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1969 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nixon Now: The Courts and the Presidency After Twenty-five Years Michael Stokes Paulsent United States v. Nixon' was, and remains today, a case of enormous doctrinal and political significance-easily one of the five most important Supreme Court decisions of the last fifty years. The decision proximately led to the forced resignation of a President of the United States from office. The decision helped spawn a semi-permanent statutory regime of Independ- ent Counsel, exercising the prosecutorial power of the United States and investigating executive branch officials 2-- a regime that has fundamentally reshaped our national politics. Nixon provided not only the political context that spawned the Inde- pendent Counsel statute, but a key step in the doctrinal evolu- tion that led the Court to uphold its constitutionality, incor- rectly, fourteen years later, in Morrison v. Olson.3 United States v. Nixon also established the principle that the President possesses no constitutional immunity from com- pulsory legal process, a holding that led almost inexorably to the Supreme Court's unanimous rejection of presidential im- munity from civil litigation for non-official conduct, twenty- three years later, in Clinton v. -

The Breadth of Congress' Authority to Access Information in Our Scheme

H H H H H H H H H H H 5. The Breadth of Congress’s Authority to Access Information in Our Scheme of Separated Powers Overview Congress’s broad investigatory powers are constrained both by the structural limitations imposed by our constitutional system of separated and balanced powers and by the individual rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights. Thus, the president, subordinate officials, and individuals called as witnesses can assert various privileges, which enable them to resist or limit the scope of congressional inquiries. These privileges, however, are also limited. The Supreme Court has recognized the president’s constitutionally based privilege to protect the confidentiality of documents or other information that reflects presidential decision-making and deliberations. This presidential executive privilege, however, is qualified. Congress and other appropriate investigative entities may overcome the privilege by a sufficient showing of need and the inability to obtain the information elsewhere. Moreover, neither the Constitution nor the courts have provided a special exemption protecting the confidentiality of national security or foreign affairs information. But self-imposed congressional constraints on information access in these sensitive areas have raised serious institutional and practical concerns as to the current effectiveness of oversight of executive actions in these areas. With regard to individual rights, the Supreme Court has recognized that individuals subject to congressional inquiries are protected by the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments, though in many important respects those rights may be qualified by Congress’s constitutionally rooted investigatory authority. A. Executive Privilege Executive privilege is a doctrine that enables the president to withhold certain information from disclosure to the public or even Congress. -

R R R ---R R R R R R R R R R R R R

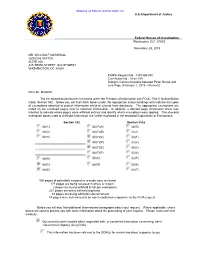

Obtained via FOIA by Judicial Watch, Inc. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 November 29, 2019 MR. WILLIAM F MARSHALL JUDICIAL WATCH SUITE 800 425 THIRD STREET, SOUTHWEST WASHINGTON, DC 20024 FOIPA Request No.: 1391365-000 Civil Action No.: 18-cv-154 Subject: Communications between Peter Strzok and Lisa Page (February 1, 2015 – Present) Dear Mr. Marshall: The enclosed documents were reviewed under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), Title 5, United States Code, Section 552. Below you will find check boxes under the appropriate statue headings with indicate the types of exemptions asserted to protect information which is exempt from disclosure. The appropriate exemptions are noted on the enclosed pages next to redacted information. In addition, a deleted page information sheet was inserted to indicate where pages were withheld entirely and identify which exemptions were applied. The checked exemption boxes used to withhold information are further explained in the enclosed Explanation of Exemptions. Section 552 Section 552a r (b)(1) r (b)(7)(A) r (d)(5) r (b)(2) r (b)(7)(B) r (j)(2) r (b)(3) P' (b)(7)(C) r (k)(1) -------- P' (b)(7)(D) r (k)(2) (b)(7)(E) (k)(3) -------- P' r -------- r (b)(7)(F) r (k)(4) (b)(4) r (b)(8) r (k)(5) (b)(5) r (b)(9) r (k)(6) (b)(6) r (k)(7) 500 pages of potentially responsive records were reviewed. 171 pages are being released in whole or in part. 2 pages are being withheld in full per exemptions. -

Executive Privilege: a Constitutional Myth

Book Reviews The Seedlings for the Forest Executive Privilege: A Constitutional Myth. By Raoul Berger. Cam- bridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1974. Pp. xvi, 430. $14.95. Reviewed by Ralph K. Winter, Jr.t I Were the author of Executive Privilege: A Constitutional Myth an academic obscurity tilling the fields of legal history, a reviewer might well resolve the conflict between magnanimity and candor in favor of the former. But Raoul Berger is a public figure, extolled in the media as an eminent authority and relied upon as the definitive scholar on questions of compelling public concern. What he writes is front page news in the New York Times,' the subject of long stories in weekly newsmagazines 2 and recommended by reviewers as important reading.3 This reader dissents. Executive Privilege: A Constitutional Myth is so inadequate as to be almost beside the point. Indeed, media praise raises serious questions about how the media choose the legal scholarship they spotlight. Only a lack of acquaintance with Berger's work or a hypocritical affinity for the immediate political implications of his conclusions can explain this enthusiasm from such unlikely sources. This is a book, for example, which strongly suggests that President Eisenhower committed an impeachable offense when he directed a Deputy General Counsel of the Defense Department not to answer Senator Joseph McCarthy's questions as to conversations within the executive branch relating to ways in which the McCarthy investigations into the Army might be stopped. 4 Berger's principal mode of analysis is far more compatible with the constitutional ap- proach of those who would have impeached Earl Warren than with that of those who would impeach Richard Nixon. -

Congress's Contempt Power and the Enforcement Of

Congress’s Contempt Power and the Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas: Law, History, Practice, and Procedure -name redacted- Legislative Attorney Updated May 12, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL34097 Congress’s Contempt Power and the Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas Summary Congress’s contempt power is the means by which Congress responds to certain acts that in its view obstruct the legislative process. Contempt may be used either to coerce compliance, to punish the contemnor, and/or to remove the obstruction. Although arguably any action that directly obstructs the effort of Congress to exercise its constitutional powers may constitute a contempt, in recent times the contempt power has most often been employed in response to non- compliance with a duly issued congressional subpoena—whether in the form of a refusal to appear before a committee for purposes of providing testimony, or a refusal to produce requested documents. Congress has three formal methods by which it can combat non-compliance with a duly issued subpoena. Each of these methods invokes the authority of a separate branch of government. First, the long dormant inherent contempt power permits Congress to rely on its own constitutional authority to detain and imprison a contemnor until the individual complies with congressional demands. Second, the criminal contempt statute permits Congress to certify a contempt citation to the executive branch for the criminal prosecution of the contemnor. Finally, Congress may rely on the judicial branch to enforce a congressional subpoena. Under this procedure, Congress may seek a civil judgment from a federal court declaring that the individual in question is legally obligated to comply with the congressional subpoena. -

John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan Pacific Cgem Orge School of Law

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2010 The akM ing of the Attorney General: John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan Pacific cGeM orge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/facultyarticles Part of the Legal Biography Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation 41 McGeorge L. Rev. 311 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review Essay The Making of the Attorney General: John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan* I. INTRODUCTION Shortly after I resigned my position as General Counsel of the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department in 1971, I was startled to receive a two-page letter from Attorney General John Mitchell. I was not a Department of Justice employee, and Mitchell's acquaintance with me was largely second-hand. The contents were surprising. Mitchell generously lauded my rather modest role "in developing an effective and professional law enforcement program for the District of Columbia." Beyond this, he added, "Your thoughtful suggestions have been of considerable help to me and my colleagues at the Department of Justice." The salutation was, "Dear Jerry," and the signature, "John." I was elated. I framed the letter and hung it in my office. -

June 1-15, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/2/1972 A Appendix “B” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/5/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/6/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/9/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/12/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1972 – June 15, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THF WHITE ,'OUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Travel Record for Travel AnivilY) f PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day. Yr.) _u.p.-1:N_E I, 1972 WILANOW PALACE TIME DAY WARSAW, POLi\ND 7;28 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ccd R=Received ACTIVITY 1----.,------ ----,----j In Out 1.0 to 7:28 P The President requested that his Personal Physician, Dr. -

August 18, 2020 VIA FOIA ONLINE Kevin Krebs Assistant Director FOIA

August 18, 2020 VIA FOIA ONLINE Kevin Krebs Assistant Director FOIA/Privacy Unit Executive Office for United States Attorneys Department of Justice 175 N Street NE, Suite 5.400 Washington, DC 20530-0001 Via FOIA Online Re: Freedom of Information Act Request Dear FOIA Officer: Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the implementing regulations of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), 28 C.F.R. Part 16, American Oversight makes the following request for records. In May 2020, Attorney General William Barr tapped U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Texas John Bash to investigate “unmasking” practices—i.e., the intelligence community practice of revealing of the identity of an individual on a monitored communication—occurring before and after the 2016 presidential election.1 The move is part of a broader DOJ investigation into unmasking, which has raised concerns about political motivations within the DOJ.2 American Oversight seeks records with potential to shed light on Mr. Bash’s actions. Requested Records American Oversight requests that your agency produce the following records within twenty business days: 1 Quint Forgey, Barr Taps U.S. Attorney to Investigate ‘Unmasking’ as Part of Russian Probe Review, Politico (May 28, 2020, 9:25 AM), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/28/barr-russia-probe-attorney-286920. 2 See, e.g., Mark Hosenball, Former U.S. Officials Question DOJ’s Probe of ‘Unmasking’ of Trump Ally, Reuters (May 29, 2020, 6:08 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa- intelligence-unmasking/former-u-s-officials-question-dojs-probe-of-unmasking-of-trump- ally-idUSKBN23519Q.