Ginger Baker's Beef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

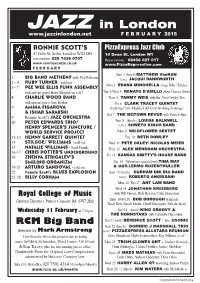

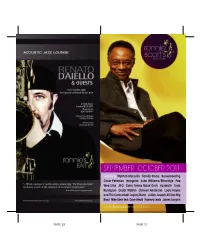

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

Varsity Jazz

Varsity Jazz Jazz at Reading University 1951 - 1984 By Trevor Bannister 1 VARSITY JAZZ Jazz at Reading University 1951 represented an important year for Reading University and for Reading’s local jazz scene. The appearance of Humphrey Lyttelton’s Band at the University Rag Ball, held at the Town Hall on 28th February, marked the first time a true product of the Revivalist jazz movement had played in the town. That it should be the Lyttelton band, Britain’s pre-eminent group of the time, led by the ex-Etonian and Grenadier Guardsman, Humphrey Lyttelton, made the event doubly important. Barely three days later, on 3rd March, the University Rag Committee presented a second event at the Town Hall. The Jazz Jamboree featured the Magnolia Jazz Band led by another trumpeter fast making a name for himself, the colourful Mick Mulligan. It would be the first of his many visits to Reading. Denny Dyson provided the vocals and the Yew Tree Jazz Band were on hand for interval support. There is no further mention of jazz activity at the university in the pages of the Reading Standard until 1956, when the clarinettist Sid Phillips led his acclaimed touring and broadcasting band on stage at the Town Hall for the Rag Ball on 25th February, supported by Len Lacy and His Sweet Band. Considering the intense animosity between the respective followers of traditional and modern jazz, which sometimes reached venomous extremes, the Rag Committee took a brave decision in 1958 to book exponents of the opposing schools. The Rag Ball at the Olympia Ballroom on 20th February, saw Ken Colyer’s Jazz Band, which followed the zealous path of its leader in keeping rigidly to the disciplines of New Orleans jazz, sharing the stage with the much cooler and sophisticated sounds of a quartet led by Tommy Whittle, a tenor saxophonist noted for his work with the Ted Heath Orchestra. -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

ISSUE 22 ° May 2011

Ne w s L E T T e R Editor: Dave Gelly ISSUE 22 ° May 2011 Ready for the Second Round We have now success- packs on the theme ‘The fully completed the devel- Story of British Jazz’, empha- opment phase of the sising the people and places Simon Spillett Talkin’ (and Access Development involved, and also the wider Playin’) Tubby Project for the Heritage social and cultural aspect of A celebration of the Music, Life Lottery Fund bid. Working the times. Some of these are NATIONAL JAZZ ARCHIVE JAZZ NATIONAL and times of the late, great British with Essex Record Office touched on in the Archive’s and Flow Associates, our exhibition at the Barbican jazz legend Tubby Hayes education and outreach Music Library (see below). With John Critchinson (piano), consultants, we have Alec Dankworth (bass) and developed our plans to Clark Tracey (drums) apply for the second NJA Exhibition Saturday 23 July 2011 round – funding of £388,000 opens at Barbican 1.30 - 4.30pm, at Loughton Methodist Church for a three-year delivery Music Library project. Tickets £10 from David Nathan at The Archive’s exhibition the Archive (cheques payable to This will involve building at the Barbican Music Library National Jazz Archive) on what we have so far is set to open on Tuesday 3rd See also Pages 5 & 6 achieved in increasing access May. It presents the people, to our collections during the places, bands and great jazz development phase - con- events, portrayed in rare serving, cataloguing, digitis- photos, posters, books, ing, developing outreach magazines and ephemera facilities, and collaborating from our fast-growing on projects with those who collection. -

Bobby Watson Kirk Knuffke Guillermo Gregorio Horace Silver Coltrane

AUGUST 2019—ISSUE 208 YOUR FREE GuiDe TO THE NYC JaZZ SCENE NYCJaZZRECORD.COM RAVICOLTRANE next trane comin’ bobby kirk GuiLLERMo horace watson knuffke GREGorio siLver Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2019—ISSUE 208 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : bobby watson 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist feature : kirk knuffke 7 by john sharpe [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : ravi coLtrane 8 by russ musto [email protected] Advertising: encore : GuiLLERMo GREGORIO 10 by steven loewy [email protected] Calendar: Lest we forGet : horace siLver 10 by scott yanow [email protected] VOXNews: LabeL spotLiGht : aLeGre recorDs 11 by jim motavalli [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or obituaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] festivaL report 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, cD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Pierre Crépon, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Miscellany Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, 31 George Grella, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event caLenDar Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, 32 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Anna Steegmann, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, George Kanzler, Improvisation is the magic of jazz. -

October 2011

SEPTEMBE R - OCTOBER 2011 Featuring: Wynton Marsalis | Family Stone | Remembering Oscar Peterson | Incognito | John Williams/Etheridge | Pee Wee Ellis | JTQ | Colin Towns Mask Orch | Azymuth | Todd Rundgren | Cedar Walton | Carleen Anderson | Louis Hayes and The Cannonball Legacy Band | Julian Joseph All Star Big Band | Mike Stern feat. Dave Weckl | Ramsey Lewis | James Langton Cover artist: Ramsey Lewis Quintet (Thur 27 - Sat 29 Oct) PAGE 28 PAGE 01 Membership to Ronnie Scotts GIGS AT A GLANCE SEPTEMBER THU 1 - SAT 3: JAMES HUNTER SUN 4: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S JAZZ ORCHESTRA PRESENTS THE GENTLEMEN OF SWING MON 5 - TUE 6: THE FAMILY STONE WED 7 - THU 8: REMEMBERING OSCAR PETERSON FEAT. JAMES PEARSON & DAVE NEWTON FRI 9 - SAT 10: INCOGNITO SUN 11: NATALIE WILLIAMS SOUL FAMILY MON 12 - TUE 13: JOHN WILLIAMS & JOHN ETHERIDGE WED 14: JACQUI DANKWORTH BAND THU 15 - SAT 17: PEE WEE ELLIS - FROM JAZZ TO FUNK AND BACK SUN 18: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S BLUES EXPLOSION MON 19: OSCAR BROWN JR. TRIBUTE FEATURING CAROL GRIMES | 2 free tickets to a standard price show per year* TUE 20 - SAT 24: JAMES TAYLOR QUARTET SUN 25: A SALUTE TO THE BIG BANDS | 20% off all tickets (including your guests!)** WITH THE RAF SQUADRONAIRES | Dedicated members only priority booking line. MON 26 - TUE 27: ROBERTA GAMBARINI | Jump the queue! Be given entrance to the club before Non CELEBRATING MILES DAVIS 20 YEARS ON Members (on production of your membership card) WED 28 - THU 29: ALL STARS PLAY ‘KIND OF BLUE’ FRI 30 - SAT 1 : COLIN TOWNS’ MASK ORCHESTRA PERFORMING ‘VISIONS OF MILES’ | Regular invites to drinks tastings and other special events in the jazz calendar OCTOBER | Priority information, advanced notice on acts appearing SUN 2: RSJO PRESENTS.. -

By John Milward

By John Milward ... HE WORD TRAFFIC IS FREQUENTLY FOLLOWED BY JAM. FOR shedding with Winwood were guitarist Dave Mason, the British rock band Traffic, the musical jam ses drummer Jim Capaldi and the horn-blowing Chris Woovd. sion began in the spring of 1967 at a country cot The resulting album, Mr. Fantasy, fit right into a year that tage in Berkshire, England. As the quartet wrote saw the release of Sgt. Pepper and the rise of San Francisco and rehearsed, member Steve Winwood’s soulful psychedelic bands Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead. voice and wailing organ could be heard on the ra And the song “Dear Mr. Fantasy” was a monster jam of key dio via “Gimme Some Lovin’ ” and “I’m a Man,” monster hits boards and guitars that could go on pretty much forever. from his previous band, the Spencer Davis Group. Now wood- In 1994, two decades after the original band broke up, Winwood and Capaldi re-formed Traf- Above: Jim Capaldi, fic and toured with the king of the jam Dave Mason, Chris bands, the Grateful Dead, who played Wood and Steve “Dear Mr. Fantasy” when Traffic did Winwood (from le ft) not. In 2002, Winwood attended the annual gathering of jam bands, the Bonnaroo Music Festival, and sat in with Widespread Panic and the String Cheese Inci dent, making his “long strange trip” slightly more typical than that of his buddies, the Dead. His journey was that of a gifted singer and musician. By expanding rock’s instrumental palette, Traffic broke new ground in popular music. -

Florida Design Naples Edition

Sofas from Century Furniture cloaked in linen and EJ Victor’s tailored club chairs shape distinct seating areas in the grand MOLLY GRUP salon. A leather cocktail ottoman from Baker exudes elegance “Inspired by the breathtaking views of the Gulf of Mexico, while translucent elements like the crystal accent table from John-Richard are harmonious with the glistening Gulf waters. I wanted to be sure the design choices did not take the eye from the view. I love the idea of interiors being clean, monochromatic and full of texture.” AS SEEN IN NAPLES EDITION FLORI DA DESIGN THE STARS WERE ALIGNED FOR THE homeowner of this 8,233-square-foot penthouse as he uncovered not one but two gems — the Le Rivage tower and interior designer Molly Grup. When the JEWEL IN THE SKY designer dug her heels into this full renovation, the owner had no idea of what was about to transpire. The result: an ultra-sleek yet sophisticated condo he now calls home. At the top of one of Naples’ most prestigious addresses, intoxicating views envelop a stellar “He described what he was looking for and gave me a lot of creative freedom,” Grup says. From space abounding with organically inspired elements and incredible surprises neutral tones to colorful artwork, the space exudes a warm vibe. Designed with unobstructed views, the open floor plan breathes in sunshine while allowing the eye to move through the space. interior design by MOLLY GRUP, FICARRA DESIGN ASSOCIATES, NAPLES, FL A “come one, come all” ambience welcomes family and friends into the grand salon, an inviting architecture by BOB VAYDA, STOFFT COONEY ARCHITECTS, NAPLES, FL builder KURTZ HOMES, NAPLES, FL area divided into sections that channel the flow of both large and intimate gatherings.