Recovery Coach Manual Substance Use Disorder Recovery Program Recovery2nd Edition, Coach Revised 2017 Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Eastern News: September 19, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep September 2003 9-19-2003 Daily Eastern News: September 19, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_sep Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: September 19, 2003" (2003). September. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_sep/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in September by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N “Tell the truth September 19, 2003 FRIDAY and don’t be afraid.” VOLUME 87, NUMBER 20 THEDAILYEASTERNNEWS.COM Panthers host Redbirds ISU’s explosive offense meets Eastern’s stifling defense Saturday at O’Brien Stadium. Page 12 SPORTS No charges filed yet in crash death N State’s attorney will determine whether to pursue action in homicide By Carly Mullady CITY EDITOR Pressing charges for a summer death ruled homicide is now in the State’s Attorney’s hands. Last Thursday, a coroner’s jury in Champaign County ruled the summer car accident death of Eastern student Sheila Sue Henson a homicide. The homicide ruling is then submitted to the state’s attorney in the county the accident occurred. “Depending on circumstances, sometimes they will press charges and sometimes they won’t,” Champaign Deputy Coroner Duane Northrup said. “The state’s attorney does not have to prosecute unless they feel there is enough evidence to prose- DAILY EASTERN NEWS PHOTOS BY COLIN MCAULIFFE cute a homicide.” Lorelei Sims, former Eastern graduate and owner of 5 Points Blacksmith located at 218 State St., works on a welding project A homicide ruling means the jury viewed a death Thursday afternoon. -

Lisa Bircher, Doctoral Candidate in EHHS, Kent State University

PART-TIME DOCTORAL STUDENT SOCIALIZATION THROUGH PEER MENTORSHIP A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College and Graduate School of Education, Health and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Lisa S. Bircher December 2012 © Copyright, 2012 by Lisa S. Bircher All Rights Reserved ii A dissertation written by Lisa S. Bircher B.S., Youngstown State University, 1993 M.S., The Ohio State University, 2002 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by __________________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee William P. Bintz __________________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Lisa Donnelly __________________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Susan V. Iverson __________________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by __________________________________, Director, School of Teaching, Learning Alexa Sandmann Curriculum Studies __________________________________, Dean, College and Graduate School of Daniel F. Mahony Education, Health, and Human Services iii BIRCHER, LISA S., Ph.D., December 2012 CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION PART-TIME DOCTORAL STUDENT SOCIALIZATION THROUGH PEER MENTORSHIP (345 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William P. Bintz, Ph.D. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to understand the socialization (Weidman, Twale, & Stein, 2001) experiences of part-time doctoral students as a result of peer mentorship in one college. Part-time doctoral -

A Perfect Circle the Outsider Renholder Apocalypse Mix Download

A Perfect Circle - The Outsider (renholder Apocalypse Mix) Download 1 / 6 A Perfect Circle - The Outsider (renholder Apocalypse Mix) Download 2 / 6 3 / 6 Check out aMOTION [Explicit] by A Perfect Circle on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or ... Unlimited MP3 £7.99 ... Buy MP3 Album £7.99 ... 3, Outsider (Apocalypse Remix), 5:28. 4, Weak And Powerless (Tilling My Grave Renholder Mix), 3:05.. Outsider (Apocalypse Remix) ... Resident Evil Afterlife Theme The Outsider - A Perfect circle [ENDSONG] · Resident Evil Afterlife - Soundtrack - The Outsider (Renholder Apocalypse Mix) ... By clicking “Agree” you allow us to use cookies on our website, social media and partner websites in order to improve and personalize our shop, and for analysis .... A Perfect Circle - The Outsider Apocalypse Mix mp3 ... Resident Evil Afterlife - Soundtrack - The Outsider Renholder Apocalypse Mix mp3 .... «The Outsider (Renholder Apocalypse Mix)» – A Perfect Circle 6. «The End of Heartache» – Killswitch Engage (the end credits song and main ... arquitectura sin arquitectos bernard rudofsky libro pdf download Listen to Outsider (Apocalypse Remix) by A Perfect Circle, 212423 Shazams, featuring on 2000s Hard Rock Essentials, and 2000s Rock Essentials Apple Music .... rk bangia law of contract ebook download rk bangia law of contract ebook download.. Alex Theme (Machine Head Mix) - Mary Elizabeth McGlynn Mp3 Download - ABLE2.ABLESERVICES.EU. ... Outsider (Apocalypse Remix) - A Perfect Circle mp3 download ... Made Of Stone (Renholdër Remix) - Evanescence mp3 download .... A perfect circle outsider apocalypse remix listen. The outsiders-a ... remix) mp3. Resident evil afterlife - soundtrack - the outsider (renholder apocalypse mix).. The Outsider (Apocalypse Mix) Lyrics: Help me if you can / It's just that this / Is not the way I'm wired so could you please / Help me understand why / You've .. -

Arbiter, October 2 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 10-2-2003 Arbiter, October 2 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. B()ISE STATE'S INDEPENDENT STU DENT NEW SPA I' E R SIN C E 19 3 J THURSDAY CELEBRATING OCTOBER 2, 2003 70 YEARS CD REVIEW , . .b.a.go'. A'Perfect Circle: . , , The Broacs battle' - page 5 The lighter side of Tool in the ·Bayou A&E-5 Idaho Wild - page 3 Sports -o WWW.ARBITERONLINE,'C()M VOLUME 16 ISSUE 13 CAMPUS SHORTS Religious activists Agency BDlse Slate Theatre looks into Arts Dpens seasen Oct. 2 with Beckett's leak of CIA "Endgame" draw crowd in quad Boise State University's operative's theater arts department opens its 2003-04 season with Samuel - Beckett's name absurdist play "Endgame." Performances are at 7: BY RICHARD B. SCHMITI' 30 p.m. Oct. 2-4 and 8- Los Angeles Times 11 and at 2 p.m, Oct. 5 Los Angeles Times-Washington and 12 at the Morrison Post News Service Center Stage II. Tickets are $9 general and $7 for WASHINGTON - The Justice students and seniors at Department has been asked Select-a-Seat. -

1200 Micrograms 1200 Micrograms 2002 Ibiza Heroes of the Imagination 2003 Active Magic Numbers 2007 the Time Machine 2004

#'s 1200 Micrograms 1200 Micrograms 2002 Ibiza Heroes of the Imagination 2003 Active Magic Numbers 2007 The Time Machine 2004 1349 Beyond the Apocalypse 2004 Norway Hellfire 2005 Active Liberation 2003 Revelations of the Black Flame 2009 36 Crazyfists A Snow Capped Romance 2004 Alaska Bitterness the Star 2002 Active Collisions and Castaways 27/07/2010 Rest Inside the Flames 2006 The Tide and It's Takers 2008 65DaysofStati The Destruction of Small 2007 c Ideals England The Fall of Man 2004 Active One Time for All Time 2008 We Were Exploding Anyway 04/2010 8-bit Operators The Music of Kraftwerk 2007 Collaborative Inactive Music Page 1 A A Forest of Stars The Corpse of Rebirth 2008 United Kingdom Opportunistic Thieves of Spring 2010 Active A Life Once Lost A Great Artist 2003 U.S.A Hunter 2005 Active Iron Gag 2007 Open Your Mouth For the Speechless...In Case of Those 2000 Appointed to Die A Perfect Circle eMOTIVe 2004 U.S.A Mer De Noms 2000 Active Thirteenth Step 2003 Abigail Williams In the Absence of Light 28/09/2010 U.S.A In the Shadow of A Thousand Suns 2008 Active Abigor Channeling the Quintessence of Satan 1999 Austria Fractal Possession 2007 Active Nachthymnen (From the Twilight Kingdom) 1995 Opus IV 1996 Satanized 2001 Supreme Immortal Art 1998 Time Is the Sulphur in the Veins of the Saint... Jan 2010 Verwüstung/Invoke the Dark Age 1994 Aborted The Archaic Abattoir 2005 Belgium Engineering the Dead 2001 Active Goremageddon 2003 The Purity of Perversion 1999 Slaughter & Apparatus: A Methodical Overture 2007 Strychnine.213 2008 Aborym -

Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Maynard James Keenan: Lyrics of Evolution; Evolution

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Antonín Zita Maynard James Keenan: Lyrics of Evolution; Evolution of Lyrics Bachelor ’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2008 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Antonín Zita Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A., for his insightful advice, support and guidance. Table of Contents Introduction……………………………...………………………..…………………….1 1. Maynard James Keenan’s Life and Works…………………………………...……3 1.1 Background………………………………………………………………..3 1.2 Note……………………………………………………………………….11 2. Evolution Lyrics…………….………………………………………………………13 2.1 Evolution through Control…………………...…………………………15 2.2 Evolution of Society………….…………………………………………..24 2.3 Furthering the Evolution………………………………………………..32 3. Religious Songs………………………………………………...……………………42 Conclusion………………………...……………………………………………………52 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….. 54 Appendix……….………………………………………………………………………65 Introduction Maynard James Keenan is the singer known from the bands Tool and A Perfect Circle as well as from his recent side project Puscifer. Beginning in 1990, Tool have become highly influential for several music movements, produced multi-platinum selling records topping the charts in several countries, and won three Grammy Awards, yet due to their intense and multi- layered music, they have remained an alternative act; A Perfect Circle met with similar response. Unlike most of music bands, Tool are a democratic group in the sense that no “spokesman” for the band exists and A Perfect Circle was started by its guitarist Billy Howerdell; however, Keenan’s lyrics are important, for they provide a context for the music. He approaches many issues in his songs, such as personal feelings, manipulation, social criticism, hypocrisy, religion or censorship. -

Music 96676 Songs, 259:07:12:12 Total Time, 549.09 GB

Music 96676 songs, 259:07:12:12 total time, 549.09 GB Artist Album # Items Total Time A.R. Rahman slumdog millionaire 13 51:30 ABBA the best of ABBA 11 43:42 ABBA Gold 9 36:57 Abbey Lincoln, Stan Getz you gotta pay the band 10 58:27 Abd al Malik Gibraltar 15 54:19 Dante 13 50:54 Abecedarians Smiling Monarchs 2 11:59 Eureka 6 35:21 Resin 8 38:26 Abel Ferreira Conjunto Chorando Baixinho 12 31:00 Ace of Base The Sign 12 45:49 Achim Reichel Volxlieder 15 47:57 Acid House Kings Sing Along With 12 35:40 The Acorn glory hope mountain 12 48:22 Acoustic Alchemy Early Alchemy 14 45:42 arcanum 12 54:00 the very best of (Acoustic Alchemy) 16 1:16:10 Active Force active force 9 42:17 Ad Vielle Que Pourra Ad Vielle Que Pourra 13 52:14 Adam Clayton Mission Impossible 1 3:27 Adam Green Gemstones 15 31:46 Adele 19 12 43:40 Adele Sebastan Desert Fairy Princess 6 38:19 Adem Homesongs 10 44:54 Adult. Entertainment 4 18:32 the Adventures Theodore And Friends 16 1:09:12 The Sea Of Love 9 41:14 trading secrets with the moon 11 48:40 Lions And Tigers And Bears 13 55:45 Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits 10 37:30 The African Brothers Band Me Poma 5 37:32 Afro Celt Sound System Sound Magic 3 13:00 Release 8 45:52 Further In Time 12 1:10:44 Afro Celt Sound System, Sinéad O'Connor Stigmata 1 4:14 After Life 'Cauchemar' 11 45:41 Afterglow Afterglow 11 25:58 Agincourt Fly Away 13 40:17 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir Saint Hubert 11 38:26 Ahmad El-Sherif Ben Ennas 9 37:02 Ahmed Abdul-Malik East Meets West 8 34:06 Aim Cold Water Music 12 50:03 Aimee Mann The Forgotten Arm 12 47:11 Air Moon Safari 10 43:47 Premiers Symptomes 7 33:51 Talkie Walkie 10 43:41 Air Bureau Fool My Heart 6 33:57 Air Supply Greatest Hits (Air Supply) 9 38:10 Airto Moreira Fingers 7 35:28 Airto Moreira, Flora Purim, Joe Farrell Three-Way Mirror 8 52:52 Akira Ifukube Godzilla 26 45:33 Akosh S. -

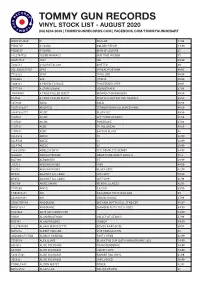

Vinyl Stock List - August 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - AUGUST 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 USI_B001655701 2PAC 2PACALYPSE NOW 49.95 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 67.99 JIV41490.1 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS 49.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 5351106 ABBA GOLD 49.99 19075850371 ABORTED TERRORVISION COLOURED VINYL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107611 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK 41.99 5107621 AC/DC POWERAGE 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 5107651 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 45 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 XLLP740 ADELE 25 29.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 M27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP048 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2012-2017 59.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 1.90296E+11 AIR CASANOVA 70 PIC DISC RSD 40 2438488481 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDE 37.99 SPINE799189 AIRBOURNE BREAKIN OUTTA HELL STND EDT 45.95 NW31135-1 AIRBOURNE DIAMOND CUTS THE B SIDES 44.99 FN279LP AK79 40TH ANNIV EDT 63.99 VS001 ALAN BRAUFMAN VALLEY OF SEARCH 47.99 M76741 ALAN PARSONS I -

Download It for Free

1 CHRISTS ANONYMOUS THE THIRTEENTH STEP 2 CHRISTS ANONYMOUS – THE THIRTEENTH STEP is createdmanifested by Harishchandra Sharma TuTu and Solvejg Sharma TuTu Translated from Danish Sixteenth Edition in process from May 2020 Free copyright Published by: The Christs Anonymous World Service Office The Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions reprinted for adaptation with permission of AA World Services, Inc. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Program of Christs Anonymous was originally suggested in the book The TuTu Doctrine – The New World Order, published by ToTos Solfond (Danish for TuTu’s Sun Foundation) as a pathway for the individual human being to go beyond his/her thinking mind, his/her Ego to his/her true Self, his/her Spirit, and thus be led to Joy of Being irrespective of circumstances. The Program has come into being with permission from ToTos Solfond without any obligations to or affiliations with ToTos Solfond otherwise. The Program has been createdmanifested as an adaptation of the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions of Alcoholics Anonymous with permission from the World Service Office of AA, Inc. without any obligations to or affiliations with Alcoholics Anonymous otherwise. 4 CONTENTS THE THIRTEENTH STEP .............................................................................................. 7 WHO IS CHRIST? ............................................................................................................ 8 WHAT IS CHRISTS ANONYMOUS? ............................................................................ 9 WHY ARE WE HERE? -

Mer De Noms a Perfect Circle Zip

Mer De Noms A Perfect Circle Zip 1 / 4 Mer De Noms A Perfect Circle Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Mer De Noms - Live by A Perfect Circle: Listen to songs by A Perfect Circle on Myspace, a place where people come to connect, discover, and .... A Perfect Circle has released three albums: their debut Mer de Noms in 2000, a follow up, Thirteenth Step in 2003, and an album of radically re-worked cover .... A personal tribute and a must have for any A Perfect Circle fan! This high quality print is featured on premium 11x17 heavy weight satin poster paper. Superior .... Order A Perfect Circle - Mer De Noms - 2 LP by A Perfect Circle for $30.95 (3/21/2019) at the Impericon Australia online store for an affordable price.. A Perfect Circle. MER DE NOMS Vinyl Record ... Perfect Circle THIRTEENTH STEP CD. A Perfect Circle ... Perfect Circle EAT THE ELEPHANT Vinyl Record. A Perfect Circle .... ON SALE. Tool Zip-Up Hoodie | Red Face & Logo Tool Hoodie.. rock musika: A Perfect Circle - Mer de Noms (2000). · 9 days ago. 5/18/2008 · That the band had in its initial pre-debut album tours performed an audacious, .... Listen free to A Perfect Circle – Mer de noms (The Hollow, Magdalena and more). 12 tracks (43:51). Mer de Noms is the first studio album by the alternative rock .... Mer de Noms is the debut studio album by American rock band A Perfect Circle. The album was released on May 23, 2000, and entered the Billboard 200 at No.. A Perfect Circle formed in 1999 with principal members Billy Howerdel (Ashes .. -

Newcomer Handbook Is Coda Conference Endorsed Literature

The Newcomer Handbook is CoDA Conference endorsed literature. Copyright 2021 Second Edition 2021 First Edition ? Date Codependents Anonymous, Inc All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or photocopied without written permission of Codependents Anonymous, Inc To obtain additional copies of The Newcomer Handbook, and all other CoDA Conference endorsed literature, contact CoDA Resource Publishing, Inc: CoRe Publications www.corepublications.org 3233 Mission Oaks Blvd Suite M Camarillo, CA 93012, USA 1-805-297-8114 [email protected] For general information about CoDA, contact: Co-Dependents Anonymous, Inc www.coda.org [email protected] PO Box 33577 Phoenix, AZ 85067-3577, USA 1-602-227-7991 Toll free: 1-888-444-2359 Spanish Toll Free: 1-888-444-2379 1 Co-Dependents Anonymous The Newcomer Handbook 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ………………………………………………………………. 4 The Five Parts of the CoDA Program of Recovery ………………... 5 I Attending Meetings ……………………………………………………. 5 II Sharing and Fellowship ……………………………………………... 21 III Working the Steps …………………………………………………… 25 IV Sponsorship …………………………………………………………. 28 V Service ………………………………………………………………... 31 Affirmations ……………………………………………………………. 37 Boundaries Within The Fellowship ………………………………… 40 Recovery Tips ………………………………………………………….. 42 Balance in Recovery ………………………………………………….. 45 Members Share Their Experience, Strength, and Hope ………... 47 What Is Codependence? .................................................................. 48 Crosstalk Defined ………………………………………………………. 49 Keep Coming Back, -

Data Visualization (CIS/DSC 468)

Data Visualization (CIS/DSC 468) Maps Dr. David Koop D. Koop, CIS 468, Spring 2017 Quantifying the Space-Efficiency of 2D Graphical Representations of Trees Michael J. McGuffin and Jean-Marc Robert Abstract— A mathematical evaluation and comparison of the space-efficiency of various 2D graphical representations of tree struc- tures is presented. As part of the evaluation, a novel metric called the mean area exponent is introduced that quantifies the distribution of area across nodes in a tree representation, and that can be applied to a broad range of different representations of trees. Several representations are analyzed and compared by calculating their mean area exponent as well as the area they allocate to nodes and labels. Our analysis inspires a set of design guidelines as well as a few novel tree representations that are also presented. Index Terms—Tree visualization, graph drawing, efficiency metrics. 1INTRODUCTION A variety of graphical representations are available for depicting tree One basic metric of space-efficiency is the total area of a representa- structures (Figure 1), from “classical” node-link diagrams [23, 7], to tion. Assuming the representation is bound within a 1 1 square, both × treemaps [14, 26, 6, 30], concentric circles [2, 27, 31], and many others icicle diagrams and treemaps (Figures 1C and 1G) have a total area of (see [13] for a survey). A major consideration when designing, eval- 1, and are equally efficient (and both optimal) according to this met- uating, or comparing such representations is how efficiently they use ric. Likewise, concentric circles and nested circles (Figures 1E and 1F) screen space to show information about the tree.