Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleats, Tucks, & Ruffles

My BERNINA BERNINA ACCESSORIES WORKBOOK PLEATS, TUCKS, & RUFFLES GATHERING PINTUCKS PINTUCKS & STITCHES PLEATING & RUFFLING NARROW TUCKS 48 My BERNINA BERNINA ACCESSORIES WORKBOOK GATHERING Gathering Foot #16 comes in two versions, one for 5.5 mm machines and one for 9 mm machines. They are both called #16 and both have a 5.5 mm needle opening. One is wider than the other and it is designed to fit the wider feed teeth of the larger machines. Supplies & Settings • Three pieces medium weight cotton, one 3” x 6” and two 4” x 12” Gathering Foot #16 • Cotton or polyester thread • Gathering Foot #16 • 80/12 Universal needle • Center needle position • Stitch: Straight Stitch Gathering Attach the gathering foot to the machine, select the Straight Stitch and adjust the stitch length to 5 mm. Swatch #1 1. Place one 12” length of fabric right side up under the foot. 2. Stitch the length of the fabric; it will gather as it goes under the needle. Swatch #2 1. Place the remaining 12” length of fabric right side up under the presser foot. Stitch 2”-3” and stop. Note: There are three things that 2. Insert the 6” length of fabric right side down into affect the amount of gathers: the slot of the foot with the raw edge against the right side of the slot. Fabric Weight—The lighter weight the 3. Continue stitching, carefully guiding both pieces of fabric, the more it gathers. fabric. Guide the fabric being gathered with the left hand and the flat piece of fabric with the right hand. -

Bernina Bernina Accessories Workbook Bernina

MYMy BERNINA BERNINA ACCESSORIES WORKBOOK BERNINA MASTERY BOOK SERIES Presser Feet and Accessories BERNINA PRESSER FEET ACCESSORIES WORKBOOK 1 ©2019 BERNINA of America. Permission granted to copy and distribute in original form only. Content may not be altered or used in any other form or under any other branding. 06022019 My BERNINA BERNINA ACCESSORIES WORKBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................... 4 CORDED EDGE ....................................... 25 FEET INFORMATION ................................ 5 NARROW HEM ....................................... 26 SEAMS ..................................................... 6 TRIMMED EDGE ..................................... 27 PATCHWORK SEAM ................................ 7 SPECIALTY FABRICS .............................. 28 STANDARD SEAM .................................... 8 SEWING JEANS & DENIM ...................... 29 KNIT SEAM ............................................... 9 SEWING LEATHER, VINYL & PLASTIC .... 30 FAGOTED SEAM .................................... 10 APPLIQUÉ & DECORATIVE STITCHES .. 31 HEMSTITCHED SEAM ............................. 11 BLANKET STITCH APPLIQUÉ .................. 32 EDGE JOINING SEAM ............................. 12 INVISIBLE APPLIQUÉ .............................. 33 FLAT FELLED SEAM ................................ 13 DECORATIVE STITCHING ....................... 34 CLOSURES ............................................. 14 QUILTING ............................................... 35 MANUAL BUTTONHOLES ..................... -

FURHTURE, TAPESTRY and EMBROIDERY of YESTERDAY AID TODAY MARLBOROUGH HOUSE Wednesday April 25™

ROYAL SCHOOL OF NEEDLEWORK Patron : H.M. QUEEN ELIZABETH THE QUEEN MOTHER LOAN EXHIBITION FURHTURE, TAPESTRY AND EMBROIDERY OF YESTERDAY AID TODAY MARLBOROUGH HOUSE Wednesday April 25™ TO Wednesday May 30™ PRICE 6 ° Ma r II)o ± ough ho use by Sir Owen Morshead. Whitehall Palace having been destroyed by fire in 1698, it was in St. James' Palace that Queen Anne set up her residence in 1702; and the Court of St. James' is still the term in official use to-day. Within a year she had created her Lord Privy Seal (John Sheffield) Duke of Buckingham, and he proceeded to erect for himself the big house looking down the length of the Mall which, rebuilt since, is known to us as Buckingham Palace. Shortly afterwards she allowed her Mistress of the Robes and close confidante, Sarah Duchess of Marlborough, to build the house in which the present exhibition is being held. From his campaign in the Low Countries the Duke had written to his wife: "You,know I never lik'd to build it at all. 'Tis not a proper Place for a great House. And I am sure," he added knowingly, "when you have built a little one you will not like it." The one which Sir Christopher Wren designed for her in 1709 is the present house minus the two top floors and certain additional rooms in the side wings. Built on so confined a site it has had to expand upwards, to the detriment of its appearance. The mettlesome Duchess was vexed by the inadequacy of its entrance from the street, and she resented too its domination by the houses in Pall Mall. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Yarn Couching

Threads n Scissors Machine Yarn Couching IMPORTANT: PLEASE READ Materials These designs are made to be used with a Freemotion Yarn Stabilizer: Couching Foot. Please check with your dealer regarding this Either two layers of foot for your machine. water soluble OR I own a Bernina Artista and use the #43 foot 1 layer of cutaway The designs are smaller than a regular design. Be sure to use a large hoop for these designs. The Yarn Couching Foot is Freemotion Yarn Couching Foot LARGER than a normal embroidery foot and needs the extra space not to hit into the hoop. 2mm diameter yarn or Before starting any Yarn Couching Design, snap the Yarn cording to be used with foot Couching Foot firmly into place, put your hoop into the ma- chine and LIFT the pressure foot. Check the design or Trace Fabric of choice, I used the design to be sure that the foot won’t hit the embroidery suede type fabric hoop when stitching. When you are sure all is right, you may start stitching your designs. Embroidery thread Follow these Instructions to continue with the stitching of your design. No 80 embroidery needle or needle rec- ommended to be used Hoop either 2 layers of water soluble stabilizer OR 1 layer of cutaway stabilizer with couching foot with your fabric. Using a normal embroidery foot, stitch out the design leaving the last color. Some of the Designs may have the same color used two or three times at the end. Don’t stitch these yet. These are color stops used for the yarn or cording. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

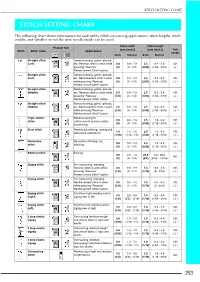

Stitch Setting Chart

STITCH SETTING CHART STITCH SETTING CHART The following chart shows information for each utility stitch concerning applications, stitch lengths, stitch widths, and whether or not the twin needle mode can be used. Stitch width Stitch length Presser foot [mm (inch.)] [mm (inch.)] Twin Stitch Stitch name Applications needle Auto. Manual Auto. Manual Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Left) etc. Reverse stitch is sewn while 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK pressing “Reverse/ (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Left) etc. Reinforcement stitch is sewn 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK while pressing “Reverse/ (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Middle) etc. Reverse stitch is sewn while 3.5 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK pressing “Reverse/ (1/8) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Middle) etc. Reinforcement stitch is sewn 3.5 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK while pressing “Reverse/ (1/8) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Triple stretch General sewing for 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 1.5 - 4.0 OK stitch reinforcement and decorative (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) topstitching Stem stitch Reinforced stitching, sewing and 1.0 1.0 - 3.0 2.5 1.0 - 4.0 OK decorative applications (1/16) (1/16 - 1/8) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) Decorative Decorative stitching, top 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 1.0 - 4.0 OK stitch stitching (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) Basting stitch Basting 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 20.0 5.0 - 30.0 NO (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/4) (3/16 - 1-3/16) Zigzag stitch For overcasting, mending. -

English Embroidery

EN GL I S H EM BROI DERY EX ECUTED PRI OR To TH E M I DDLE O F THE X V I C ENTURY Tr Burlington F ine Arts Club E X H I B I T I O N EN GL SH EM BRO D ERY E X EC UT E D PR I OR T O THE M IDDLE OF THE XVI CENT URY L O N D O N P RI N TE D F OR T H E B U RL I N GT O N F I N E ARTS CL U B I 90 5 I WI K P W I I M A N D CH S C RES S : CHARL ES H TT N GHA CO . TOOKS COU RT C ANCERY L ANE L OND ON . , H , COM M ITTEE FOR TH IS EXHIBITION P A P O N K . S . D L U . S I R C R C AR E , C I E . P E . A L D V N O S P S . Y . C RI A E RT , Q , A . G N E S P S . V D . D . E ERAR R E E , Q (ROUGE RAGON) , H B KY LL S I R E R E RT J E , K E K N S . A . F D . E RI C , Q L O N D . L N D Y E S P . S . A E AR C I SA , Q , . - A . Y F . S . O . O O N L U . L F L I E T C CR T S , LIST OF CONTRI BUTORS THE RECTOR AND CHURCHWARDEN OF THE RECTOR AND CHURCHWARDENS OF H TT B S T M . -

Silverwork and Sequins

Session 2: Cornucopia II: Silverwork and sequins In this session you will be learning how to couch metallic threads, both Jap Thread and twist. You will also learn how to stitch sequins in place using a bead. Metallic threads add a touch of sparkle to your embroidery designs. They are made by tightly wrapping a flat metallic strip around a core of cotton or silk thread. This produces a shiny thread which can be bought in a range of sizes. There are particular ways of stitching with metallic threads which you will learn in this session. MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT NEEDED FOR THIS SESSION: • Embroidery hoop or small frame • Embroidery scissors • Needles: o Crewel/embroidery needle size 10/12 o Large-eyed needle such as a chenille or tapestry needle (large enough to take the metallic threads) • The worked embroidery from Session 1: Cornucopia I: Blackwork Infills • Silver Jap Thread • Silver Twist Thread (or DMC silver metallic stranded thread) • Grey sewing cotton • Silver sequins, 3-4 mm, either round or flower-shaped or both: about 5-6 in total • Silver or clear seed beads, one per sequin plus one spare READ ALL OF THE INSTRUCTIONS THROUGH BEFORE YOU START YOUR EMBROIDERY. WORKING THE EMBROIDERY: HORN-OF-PLENTY SECTIONS 1. Place your worked piece from Session 1: Cornucopia I: Blackwork Infills in your hoop or frame (if it isn’t still there!) 2. You are going to use a technique called COUCHING to stitch the silver threads in position on your embroidery. Metallic threads are often too heavy to stitch through the fabric and the outer metallic cover will separate off if you take them through the fabric too often. -

The Melk Chasuble, an Opus Anglicanum

THE MELK CHASUBLE, AN OPUS ANGLICANUM BY HANNA KRONBERGER-FRENTZEN F late years the great artistic and paintings is also to be found in the beautiful technical merit of early English em- needlework of the Melk Chasuble. broidery and its widespread diffusion The subject of the crucifixion is often used in in various parts of Europe, has been English embroidery. It is to be met with in demonstrated again and again. Thus nearly all the famous series of designs with the oldest chasuble [PLATES A and B] of Melk which vestments are usually decorated. But Cathedral, hitherto regarded as an unknown there it always formed part of all the other piece of embroidery, must now be recognized as scenes, except that it is placed in the centre in Opus Anglicanum. Professor Tietze 1 mentions order to emphasize its significance. Thus we this chasuble as an iconographically interest- find it-to mention only a few-on the famous ing specimen of the early fourteenth century, Syon cope in the Victoria and Albert Museum without stating its origin. In spite of every and on those in the Vatican,5 also on that in the effort, it has proved impossible to trace how the Museo Civico in Bologna, and on that in Ascoli- chasuble found its way to the Treasury of the Piceno (the latter being the gift of Pope Nicholas Cathedral. Perhaps we may assume a certain IV). In the rare cases where the Crucifixion connexion with the cope, which until lately occurs alone, it is on a very small scale. It may belonged to the Cathedralof Salzburg and which be seen on the front of a burse (T. -

DP-L'art En Broderie Au Moyen

ENGLISH GLOSSARY Maniple : short band of fabric worn over the left arm, exclusively during Mass, by all clerics. Almoner (alm purse) : purse worn on the belt, closed with a flap or cords. Variable in size and shape, it is an accessory to the Membrane threads : organic metal thread consisting of gilt female and male costume. animal membrane entwined around a fibrous core. Mitre : liturgical headdress and badge of honour worn by bishops Antependium or altar frontal : textile decoration hung vertically and some abbots (i.e. “mitred” abbots). A mitre consists of before an altar. two shield-shaped halves that come to a point and two fringed streamers that hang from the base of the back, called lappets. Appliqué embroidery : technique consisting of attaching pieces of fabric, leather, parchment, etc. to a textile by sewing them onto Organic metal thread : narrow strip of organic material (leather, the ground weave. animal gut, etc.) gilt in silver or gold and wrapped around a fibrous core. Buckram : plant-based fabric used as a lining. Orphrey : woven bands, sometimes embroidered, sewn onto Bullion or purl thread : fine gold thread wound around a needle to liturgical vestments for embellishment. form a hollow spiral. Patterned weave : woven textile decorated with a more or less Chasuble : outer liturgical vestment, open on the sides, worn complex pattern obtained by crossing the threads of the warp by clerics celebrating Mass. A chasuble, stole and maniple are and the weft. generally worn together. Raised embroidery : unlike flat embroidery, embroidery that is Cope : ample liturgical vestment worn by clerics during religious elevated from the ground fabric thanks to padding, (large waxed services. -

From Secular World Into Sacred Space Examples of Liturgical Vestments and Other Paraments from the Collections of the National Museum in Krakow

Many Ways of Personal Piety – From Secular World into Sacred Space Examples of Liturgical Vestments and Other Paraments from the Collections of the National Museum in Krakow Joanna Regina Kowalska The National Museum in Krakow, Poland Abstract: Personal piety could be expressed by presenting the Church with beautiful liturgical vest- ments. Their richness depended on the wealth of a donor. The richest could afford the most expensive fabrics and the most skilled craftsmen. But the need of a personal donation was also very strong among less wealthy people. The Church was given women’s dresses, silk sashes or embroideries taken from the caparisons. All these donations were carefully exam- ined and the most suitable were remade into liturgical vestments. In the collections of the National Museum in Krakow one can find paraments made of fabrics taken from secular out- fits, mostly women’s skirts and silk sashes of Polish noblemen’s costume. Quite interesting are also home-made paraments offered as pious donations. We will see that the history of liturgical vestments can be fascinating and it is always worthwhile examining them carefully even if their artistic quality is not the highest one. Contents: Introduction / The Chasuble from Lelów (17th – 19th cent.) / Paraments Made of Silk Sashes (18th – 19th cent.) / Paraments Made of Embroideries Taken from Women’s Skirts (18th – 19th cent.) / Liturgical Vestments Made by Pious Women / Conclusion / References / Picture Credits Introduction Personal piety could be expressed by presenting the Church with beautiful liturgical vest- ments. Their richness depended on the wealth of a donor. The richest could afford the most expensive fabrics and the most skilled craftsmen.