Revisiting Smith's Vexillological Classification System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

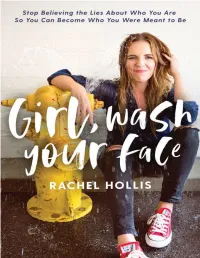

Girl, Wash Your Face

PRAISE FOR Girl, Wash Your Face “If Rachel Hollis tells you to wash your face, turn on that water! She is the mentor every woman needs, from new mommas to seasoned business women.” —ANNA TODD, New York Times and #1 internationally bestselling author of the After series “Rachel’s voice is the winning combination of an inspiring life coach and your very best (and funniest) friend. Shockingly honest and hilariously down to earth, Girl, Wash Your Face is a gift to women who want to flourish and live a courageously authentic life.” —MEGAN TAMTE, founder and co-CEO of Evereve “There aren’t enough women in leadership telling other women to GO FOR IT. We typically get the caregiver; we rarely get the boot camp instructor. Rachel lovingly but firmly tells us it is time to stop letting the tail wag the dog and get on with living our wild and precious lives. Girl, Wash Your Face is a dose of high-octane straight talk that will spit you out on the other end chasing down dreams you hung up long ago. Love this girl.” —JEN HATMAKER, New York Times bestselling author of For the Love and Of Mess and Moxie and happy online hostess to millions every week “In Rachel Hollis’s first nonfiction book, you will find she is less cheerleader and more life coach. This means readers won’t just walk away inspired, they will walk away with the right tools in hand to actually do their dreams. Dream doing is what Rachel is all about it. -

Heraldry in the Republic of Macedonia (1991-2019)

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 1 September 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202109.0027.v1 Article Heraldry in the Republic of Macedonia (1991-2019) Jovan Jonovski1, * 1 Macedonian Heraldic Society; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +38970252989 Abstract: Every country has some specific heraldry. In this paper, we will consider heraldry in the Republic of Macedonia, understood by the multitude of coats of arms, and armorial knowledge and art. The paper covers the period from independence until the name change (1991-2019). It co- vers the state coat of arms of the Republic of Macedonia especially the 2009 change. Special atten- tion is given to the development of the municipal heraldry, including the legal system covering the subject. Also personal heraldry developed in 21 century is considered. The paper covers the de- velopment of heraldry and the heraldic thought in the given period, including the role of the Macedonian Heraldic Society and its journal Macedonian Herald in development of theoretic and practical heraldry, as well as its Register of arms and the Macedonian Civic Heraldic System. Keywords: Heraldry in Macedonia; Macedonian civic heraldry; Republic of Macedonia. 1. Introduction The Republic of Macedonia became independent from the Socialist Federative Re- public of Yugoslavia with the Referendum of 8 September 1991. The Democratic Federal Macedonia was formed during the first session of the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the Na- tional Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) on 2 August 1944 (it later became the People’s Republic of Macedonia, a federal unit of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia). -

Memorandum of the Secretariat General on the European Flag Pacecom003137

DE L'EUROPE - COUNCIL OF EDMFE Consultative Assembly Confidential Strasbourg,•15th July, 1951' AS/RPP II (3) 2 COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PROCEDURE AND PRIVILEGES Sub-Committee on Immunities I MEMORANDUM OF THE SECRETARIAT GENERAL ON THE EUROPEAN FLAG PACECOM003137 1.- The purpose of an Emblem There are no ideals, however exalted in nature, which can afford to do without a symbol. Symbols play a vital part in the ideological struggles of to-day. Ever since there first arose the question of European, organisation, a large number of suggestions have more particularly been produced in its connection, some of which, despite their shortcomings, have for want of anything ;. better .been employed by various organisations and private ' individuals. A number of writers have pointed out how urgent and important it is that a symbol should be adopted, and the Secretariat-General has repeatedly been asked to provide I a description of the official emblem of the Council of Europe and has been forced to admit that no such emblem exists. Realising the importance of the matter, a number of French Members of Parliament^ have proposed in the National Assembly that the symbol of the European Movement be flown together with the national flag on public buildings. Private movements such as'the Volunteers of Europe have also been agitating for the flying of the European Movement colours on the occasion of certain French national celebrations. In Belgium the emblem of the European Movement was used during the "European Seminar of 1950" by a number of *•*: individuals, private organisations and even public institutions. -

Eflags03.Pdf

ISSUE 3 March 2007 Greetings all Flag Institute members and welcome to our third edition of eFlags. As you can see we have developed our logo a bit now….at least it’s memorable! This edition seems to have developed something of an African theme growing out of the chairman’s visit to the cinema to see the ‘Last King of Scotland’ (an amazing and flesh cringing film…well worth a visit by the way). Events have also moved fast in the Institute’s development, and we hope the final section will keep you all in touch. Please do think about coming to one of our meetings, they are great fun, ( its one of the few occasions when you can talk about flags and not face the ridicule of your family or friends!) and we have a line up of some fascinating presentations. As always any comments or suggestions would be gratefully received at [email protected] . THE EMPEROR, THE MIGHTY WARRIOR & THE LORD OF THE ALL THE BEASTS page 2 NEW FLAG DISCOVERED page 9 FLAGS IN THE NEWS page 10 SITES OF VEXILLOGICAL INTEREST page 11 PUTTING A FACE ON FLAGS page 12 FLAG INSTITUTE EVENTS page 13 NEW COUNCIL MEMBERS page 14 HOW TO GET IN TOUCH WITH THE INSTITUTE page 15 1 The Emperor, the Mighty Warrior and the Lord of All the Beasts. The 1970s in Africa saw the rise of a number of ‘colourful’ figures in the national histories of various countries. Of course the term ‘colourful’ here is used to mean that very African blend of an eccentric figure of fun, with brutal psychopath. -

Flag Research Quarterly, August 2016, No. 10

FLAG RESEARCH QUARTERLY REVUE TRIMESTRIELLE DE RECHERCHE EN VEXILLOLOGIE AUGUST / AOÛT 2016 No. 10 DOUBLE ISSUE / FASCICULE DOUBLE A research publication of the North American Vexillological Association / Une publication de recherche de THE FLAGS AND l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie SEALS OF TEXAS A S I LV E R A NN I V E R S A R Y R E V I S I O N Charles A. Spain I. Introduction “The flag is the embodiment, not of sentiment, but of history. It represents the experiences made by men and women, the experiences of those who do and live under that flag.” Woodrow Wilson1 “FLAG, n. A colored rag borne above troops and hoisted on forts and ships. It appears to serve the same purpose as certain signs that one sees on vacant lots in London—‘Rubbish may be shot here.’” Ambrose Bierce2 The power of the flag as a national symbol was all too evident in the 1990s: the constitutional debate over flag burning in the United States; the violent removal of the communist seal from the Romanian flag; and the adoption of the former czarist flag by the Russian Federation. In the United States, Texas alone possesses a flag and seal directly descended from revolution and nationhood. The distinctive feature of INSIDE / SOMMAIRE Page both the state flag and seal, the Lone Star, is famous worldwide because of the brief Editor’s Note / Note de la rédaction 2 existence of the Republic of Texas (March 2, 1836, to December 29, 1845).3 For all Solid Vexillology 2 the Lone Star’s fame, however, there is much misinformation about it. -

Executive Office of the Governor Flag Protocol

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR FLAG PROTOCOL Revised 9/26/2012 The Florida Department of State is the custodian of the official State of Florida Flag and maintains a Flag Protocol and Display web page at http://www.dos.state.fl.us/office/admin-services/flag-main.aspx. The purposes of the Flag Protocol of the Executive Office of the Governor are to outline the procedures regarding the lowering of the National and State Flags to half-staff by directive; to provide information regarding the display of special flags; and to answer frequently asked questions received in this office about flag protocol. Please direct any questions, inquires, or comments to the Office of the General Counsel: By mail: Executive Office of the Governor Office of the General Counsel 400 South Monroe Street The Capitol, Room 209 Tallahassee, FL 32399 By phone: 850.717.9310 By email: [email protected] By web: www.flgov.com/flag-alert/ Revised 9/26/2012 NATIONAL AND STATE FLAG POLICY By order of the President of the United States, the National Flag shall be flown at half-staff upon the death of principal figures of the United States government and the governor of a state, territory, or possession, as a mark of respect to their memory. In the event of the death of other officials or foreign dignitaries, the flag is to be flown at half-staff according to presidential instructions or orders, in accordance with recognized customs or practices not inconsistent with law. (4 U.S.C. § 7(m)). The State Flag shall be flown at half-staff whenever the National Flag is flown at half-staff. -

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Sebastià Herreros i Agüí Abstract Modernism (Modern Style, Modernisme, or Art Nouveau) was an artistic and cultural movement which flourished in Europe roughly between 1880 and 1915. In Catalonia, because this era coincided with movements for autonomy and independence and the growth of a rich bourgeoisie, Modernism developed in a special way. Differing from the form in other countries, in Catalonia works in the Modern Style included many symbolic elements reflecting the Catalan nationalism of their creators. This paper, which follows Wladyslaw Serwatowski’s 20 ICV presentation on Antoni Gaudí as a vexillographer, studies other Modernist artists and their flag-related works. Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Josep Llimona, Miquel Blay, Alexandre de Riquer, Apel·les Mestres, Antoni Maria Gallissà, Joan Maragall, Josep Maria Jujol, Lluís Masriera, Lluís Millet, and others were masters in many artistic disciplines: Architecture, Sculpture, Jewelry, Poetry, Music, Sigillography, Bookplates, etc. and also, perhaps unconsciously, Vexillography. This paper highlights several flags and banners of unusual quality and national significance: Unió Catalanista, Sant Lluc, CADCI, Catalans d’Amèrica, Ripoll, Orfeó Català, Esbart Català de Dansaires, and some gonfalons and flags from choral groups and sometent (armed civil groups). New Banner, Basilica of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 506 Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Background At the 20th International Conference of Vexillology in Stockholm in 2003, Wladyslaw Serwatowski presented the paper “Was Antonio Gaudí i Cornet (1852–1936) a Vexillographer?” in which he analyzed the vexillological works of the Catalan architectural genius Gaudí. -

THE LION FLAG Norway's First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard

THE LION FLAG Norway’s First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard On 27 February 1814, the Norwegian Regent Christian Frederik made a proclamation concerning the Norwegian flag, stating: The Norwegian flag shall henceforth be red, with a white cross dividing the flag into quarters. The national coat of arms, the Norwegian lion with the yellow halberd, shall be placed in the upper hoist corner. All naval and merchant vessels shall fly this flag. This was Norway’s first national flag. What was the background for this proclamation? Why should Norway have a new flag in 1814, and what are the reasons for the design and colours of this flag? The Dannebrog Was the Flag of Denmark-Norway For several hundred years, Denmark-Norway had been in a legislative union. Denmark was the leading party in this union, and Copenhagen was the administrative centre of the double monarchy. The Dannebrog had been the common flag of the whole realm since the beginning of the 16th century. The red flag with a white cross was known all over Europe, and in every shipping town the citizens were familiar with this symbol of Denmark-Norway. Two variants of The Dannebrog existed: a swallow-tailed flag, which was the king’s flag or state flag flown on government vessels and buildings, and a rectangular flag for private use on ordinary merchant ships or on private flagpoles. In addition, a number of special flags based on the Dannebrog existed. The flag was as frequently used and just as popular in Norway as in Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars Result in Political Changes in Scandinavia At the beginning of 1813, few Norwegians could imagine dissolution of the union with Denmark. -

Flag of United Arab Emirates - a Brief History

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers Flag of United Arab Emirates - A Brief History Where In The World Trivia The designer of the flag, Abdullah Mohammad Al Maainah, didn’t realise his design had been chosen until it was raised on the flagpole in 1971. Technical Specification Adopted: 2nd December 1971 Proportion: 1:2 Design: A green-white-black horizontal tricolour with a vertical red band on the right Colours: PMS Green: 355 Red: 032 Brief History In 1820 Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah and Umm al-Quwain joined together to create the Trucial States that were allied with the United Kingdom. The flag adopted to represent this alliance was a red-white-red horizontal triband with a seven pointed gold star. Between 1825 and 1952 Dubai, Kalba and Fujairah also joined the alliance The United Arab Emirates was founded in 1971 when seven of the emirates of the previous Trucial States joined together to create a single independent country. The Pan-Arab green, red, white and black colours were used for the flag which is a green-white-black horizontal tricolour with a vertical red band on the right. The government and private schools raise the flag and play the national anthem every morning. The Flag of the Trucial States The Flag of the United Arab Emirates (1820 – 1971) (1971 to Present Day The Flags of the Emirates in the United Arab Emirates Since 1968 the flag of Abu Dhabi has been a 1:2 proportioned red field with a white rectangle top left. -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Commission Report Final UK

JOINT COMMISSION ON VEXILLOGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES of The Flag Institute and North American Vexillological Association ! ! THE COMMISSION’S REPORT ON THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF FLAG DESIGN 1st October 2014 These principles have been adopted by The Flag Institute and North American Vexillological Association | Association nord-américaine de vexillologie, based on the recommendations of a Joint Commission convened by Charles Ashburner (Chief Executive, The Flag Institute) and Hugh Brady (President, NAVA). The members of the Joint Commission were: Graham M.P. Bartram (Chairman) Edward B. Kaye Jason Saber Charles A. Spain Philip S. Tibbetts Introduction This report attempts to lay out for the public benefit some basic guidelines to help those developing new flags for their communities and organizations, or suggesting refinements to existing ones. Flags perform a very powerful function and this best practice advice is intended to help with optimising the ability of flags to fulfil this function. The principles contained within it are only guidelines, as for each “don’t do this” there is almost certainly a flag which does just that and yet works. An obvious example would be item 3.1 “fewer colours”, yet who would deny that both the flag of South Africa and the Gay Pride Flag work well, despite having six colours each. An important part of a flag is its aesthetic appeal, but as the the 18th century Scottish philosopher, David Hume, wrote, “Beauty in things exists merely in the mind which contemplates them.” Different cultures will prefer different aesthetics, so a general set of principles, such as this report, cannot hope to cover what will and will not work aesthetically. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed.