Dutch Science Shops: Matching Community Needs with University R&D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting New Science Shops

PERARES Deliverable D4.2 Supporting new Science Shops Report describing the implementation phase of the local Public Engagement with Research action plans, mentoring and advisory activities, and Summer Schools Dr. Henk A.J. Mulder (editor) Science Shop, University of Groningen May 2014 This publication and the work described in it are part of the project Public Engagement with Research and Research Engagement with Society – PERARES which received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 244264 Contact details for editor: Dr. Henk A.J. Mulder, Science Shop, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The chapters in this report are written by many colleagues from the ten new Science Shop initiatives. Many thanks go to the mentors and Summer School teachers. Disclaimer: PERARES is an FP7 project funded by the European Commission. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. 2 Executive Summary Science Shops are units that perform or broker research with and for Civil Society Organisations, in a demand driven way. They are often, but now always, based at universities. This allows them to use students to do the research under faculty supervision. Thus, the research is part of the core-business of the university (research driven learning and teaching), and the public engagement is added-in to these activities, and not added-on. This makes Science Shops an affordable tool for science-society engagement and co- creation of new knowledge. -

Science Shops � Knowledge for the Community

Science Shops " knowledge for the community EUR 20877 Table of contents Foreword . .3 Rainer Gerold, Science and Society Director at the European Commission’s Research Directorate-General, shares his thoughts on science shops Community service . .4 An introduction to science shops Behind the counter . .5 The inner workings of science shops Science shops in action . .6 A behind-the-scenes tour of science shops and other community structures in Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom Talking shops . .10 Experts and prominent officials share their views on the role of science shops in Europe and beyond The rewards of community work . .12 What draws researchers to volunteer their time and effort for science shops Europe: international trendsetter . .13 A look at the community-based research movements in the United States and Canada and how European science shops helped shape their transatlantic counterparts Activities funded by the Commission . .15 Outlines the different ways in which the European Commission supports science shops Setting up shop . .16 New science shops often receive a helping hand from their established ‘cousins’ Useful information . .18 2 The ISSNET network and other useful information Science Shops Foreword here are more scientists in the world corridors of the research community for The European Union is not just about insti- T today than ever before and we depend science to better serve the citizen. However, tution building and bringing Member States on science and its applications in almost in order to serve the community, science closer together, it is also about bringing every aspect of our lives, yet we do not needs to get closer to it. -

Science Shops As University-Community Interfaces: an Interactive Approach in Science Communication

International Symposium on Public Communication of Science and Technology (PCST), Beijing, China, 21-24 June 2005 SCIENCE SHOPS AS UNIVERSITY-COMMUNITY INTERFACES: AN INTERACTIVE APPROACH IN SCIENCE COMMUNICATION H.A.J. Mulder1 and C.F.M. de Bok2 1Chemistry Shop, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, NL-9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands 2Science Shop for Biology, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, NL-3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands ABSTRACT Science shops provide independent, participatory research support to civil society. They both use traditional science communication techniques to produce usable results, and they are part of an interactive science communication system: They help articulate civil society issues and support the use of results, and they put citizens requests on the research agenda. They can have a special position as facilitators in risk communication as an independent, trusted source. Science shops benefit research, higher education and civil society simultaneously. The E.U. supports science shops to help close the gap between science and society. Science shops proved viable in different countries, provided there is demand for knowledge and supply of researchers (e.g. students for credits), with willing hosts (like universities) and available paid staff. There should be more studies on this method for interactive science communication from the democratic motive, to strengthen it and improve its impact. INDEX TERMS science shops, interactive science communication, risk communication INTRODUCTION With the start of the Science and Society Program in 2001, the European Commission started to look for ways to create a better interaction between science and society. One of their focal points is the “Science Shop”, a Dutch invention from the 1970s, which has spread to a number of other countries as well. -

Breaking out of the Local: International Dimensions of Science Shops

Breaking Out of the Local: International dimensions of science shops CASPAR DEBOK AND NORBERT STEINHAUS hat is the air quality like, right here, at my front door, W downtown in this big city? This question has been put many times in recent years to Science Shops. There is a growing concern among citizens on local air quality and the impact it is having on their health. City traffic is becoming more and more dense, traffic jams are on the rise and rush hours last longer. There is more traffic and more pollution from cars. In 2006 the European Environment Agency (EEA) published a report on air pollution at street level in European cities (EEA 2006). The EEA concludes that traffic-related air pollution is still one of the most pressing problems in urban areas. Human exposure to increased concentrations of pollutants, especially the so-called fine particles, in densely populated urban areas is high. Air quality controls, which are aimed at protecting public health, are frequently exceeded, especially in streets and other urban hotspots. More generally, Science Shops, as well as regional and local Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), have been confronted with an Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement No 1 (2008): 165–178 © UTSePress and the authors Gateways | De Bok & Steinhaus increasing number of requests from citizens on local environmental issues. Many of these requests focus on the lack of information that is available for citizens. The Aarhus Convention, signed by many countries of the United Nations in 1998 and brought into force in 2001, obliges local governments to inform citizens about local environmental conditions and to create opportunities for citizens to participate in (environmental) decision-making processes at the local level. -

Henk Mulder – Mentoring Among Science Shops

faculty of mathematics science shop and natural sciences Date 11-05-2012 | 1 Mentoring among Science Shops Henk Mulder, Science Shop/Science & Society Group, University of Groningen, The Netherlands [email protected] faculty of mathematics science shop and natural sciences Date 11-05-2012 | Role of Mentors › Making Visits: . Lectures, Talks, Speeches (ppt’s to share); different target groups (Lobby, PR, training) . Participate in discussions, meetings, workshops . Give on-the-job advice (eg curriculum inclusion) . Support pilots (/w students) › Receiving visitor . Discussion / Introduction (but: language) . Introduction of operational procedures › Summerschools + FAQs online Toolbox faculty of mathematics science shop and natural sciences Date 11-05-2012 | Pilot Project › Civil society partner (preferably) › Knowledge available, low risk › Short › Good publicity potential › Involve students Outcome as PR to start broader science shop 3 faculty of mathematics science shop and natural sciences Date 11-05-2012 | 4 Mentoring: Romania › Romania (Phase 1) 1998-2000 (4 cities) . Mentored shops: 2 x 0.5 fte/2yr . Mentors: … › Romania (Phase 2) 2002-2005 (8 cities) . 4 from phase 1: 3 yr/0.5 fte . 4 new: 3 yr/2x0.5 fte . 2 fte network . Mentors: 0.5 fte faculty of mathematics science shop and natural sciences Date 11-05-2012 | 5 TRAing and Mentoring of Science shops (TRAMS), EU 2005-2008 › Mentoring & Training (10 sites) . 37 days mentors . 5-10 days each mentored partner . Toolbox › Cachan (F), TIMCED-Ploiesti (RO), National Network (RO), STEP-C (Crete), CREA (Barcelona), Science Shops Belgium, TU Iceland, TU Tallinn (EST), Haceteppe (Ankara), Baltic Inst. Soc. Sciences (LV) faculty of mathematics science shop and natural sciences Date 11-05-2012 | 6 PERARES, EU 2010-2014 › WP4: Mentoring & Training . -

An Innovative Civil Society

AN INNOVATIVE CIVIL SOCIETY Wednesday, April 9th Welcome by Michael Søgaard Jørgensen & Søsser Brodersen 09:00 Welcome by professor Christian Clausen, Center for Design, Innovation and Sustainable Development, Aalborg University Welcome by Dr. Henk Mulder & Norbern Steinhaus Plenary: Citizens, Science, and Democracy Facilitator: Michael Søgaard Jørgensen - DIST Aalborg University Alan Irwin, Copenhagen Business School: Public Engagement with Science: from deficit to democracy – and back again? (202) Katrin Vohland, Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Research: Citizen Science and democracy – challenges and difficulties (205) David Stanners, European Environmental Agency: Improving the science policy interface by engaging with citizens (201) Martine Legris Revel, University of Lille 2 CERAPS: The scientific activity in the prism of the participatory imperative (180) 12:00 Lunch break Plenary: Funding research with and for civil society Session facilitator: Norbert Steinhause, Science Shop Bonn Gilles Laroche, Head of Unit of Science with and for Society, DG Research and Innovation, EC - The role of Responsible Research and Innovation 13:00 to foster institutional change: empowering research organisations to take-up public engagement in research and innovation Katrin Grüber, Institut Mensch, Ethik und Wissenschaft (IMEW) Berlin - Funding Schemes as Potential Barriers to Transferring Societal Problems to Research Questions (167) Emma McKenna, Science Shop Belfast - Experiences on research with and for civil -

International Student Guide 2 1

International Student Guide 2 1 2 Contents PAGE European University Cyprus Highlights 2 European University Cyprus 5 2 - Schools and Departments 5 1 QS Top Universities (QS StarsΤΜ) Distinction 7 Research, Collaborations & Strategic Agreements 9 - Microsoft Innovation Center 9 - The University signs Magna Charta Universitatum 9 - U-Multirank Ranking 9 - UI GreenMetric World Ranking 9 - Strategic Collaboration Agreements with Greek Universities and Higher Technological Institutes 10 - Breakthroughs in Pioneering Research 10 - “Science Shop” 11 - Professional Recognition 11 - ‘HR Excellence in Research Logo’ 11 - The Library 11 ERASMUS+ 13 - ERASMUS+ Participation 13 - Student Testimonials 13 Admission 14 - General Admission Requirements 15 - Undergraduate Students Admission Requirements 16 - Graduate Students Admission Requirements 16 - PhD Students Admission Requirements 17 - Visa Requirements (Non - EU students) 18 Accommodation and Cost of Living 21 Employability 23 - Career Center 23 Student Events and Conferences 24 - Cyprus Annual Medical Students Meeting (CAMESM) 25 - First prize at the Researcher’s Night 2017 25 - First Prize Pancyprian Educational Robotic Olympiad 25 - ‘Motion Vibes’ an Innovative Education Project 25 Student Life and Services 27 - Fitness Center 27 Students Share Their Views 29 Schools and Programs of Study 30 - The School of Business Administration 31 - The School of Humanities, Social and Education Sciences 32 - The School of Sciences 34 - The School of Law 35 - The School of Medicine 36 - Τhe Distance Learning -

Counter-Research: a History of Science Shops in the Netherlands

Counter-research: A History of Science Shops in the Netherlands Master’s Thesis UU History and Philosophy of Science Jurgen Sijbren Sijbrandij, 3865916 Utrecht, 8 December 2017 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. L.T.G. Theunissen Second reader: Dr. D.M. Baneke 1 Table of contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter I: From democratization movements to the first science shops ............................................... 7 Chapter II: Science shops in practice ..................................................................................................... 18 Chapter III: Challenges for science shops .............................................................................................. 28 Chapter IV: Closing down science shops ............................................................................................... 42 Chapter V: Socially oriented research in the 21st century ..................................................................... 50 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 62 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................... 68 Appendix ............................................................................................................................................... -

Science Shops in Europe: the Public As Stakeholder

Science and Pubtic Poticy, volume 31, number 3. June 2004, pages 199-211, Beech Tree Publishing. 10 Watford Close, Guildford, Surrey GUI 2EP, England Science shops Science shops in Europe: the public as stakeholder Corinna Fischer, Loet Leydesdorff and Malte Schophaus After two decades of relative silence, science shops HE SCIENCE SHOP MODEL seems to be seem to be back on the agenda of science pol- back on the agenda of science policy-making icy-making. In this article, country-specific and Tin Europe (Hellemans, 2001; Farkas, 2002). country-independent factors for their success and New science shops are being founded, like the failure and their co-operation with civil society are Brunei University Science Shop (BUSS) in London discussed in terms of different traditions in politi- (August 2002), which is funded by the Higher Edu- cation Active Community Fund, and two new ones cal culture. Science shops seem to be at a cross- in Belgium (at the University of Antwerp and the roads, where their work focus and their coalitions University of Brussels, 2003).' may have to change. On the one hand, they are The European Commission in its Science and So- still connected to their roots, the social move- ciety Action Plan of 4 December 2001, stated that ments. On the other hand, a general trend towards more than 60 science shops exist in Europe, mainly business co-operation in science policy can be ob- in the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, the United served. The increasing debate about science and Kingdom, and France. The Commission proposed an society interfaces lends importance to the science action plan to enhance the networking of science shop concept, as is especially visible in the recent shops and the creation of a structure for the inven- support given them by the European Commission. -

30 Years Bonn Science Shop

WILA Wissenschaftsladen Bonn ANNIVERSARY EDITION 30 YEARS BONN SCIENCE SHOP il Society Civ fer ans Tr ge act led o w t o Kn w o n y k it to il b a n e i t a a t c s u u d S e o t 2 Guiding Principles Education - Knowledge - Action: All the projects and events at Bonn Science Shop (WILA Bonn) are governed by the aim of enabling people to use their knowledge in order to make social changes in their natural and societal environment possible. But action can only be undertaken by those who have understood the societal challenges and the Education options available for action. This is why people‘s education is one of Bonn Science Shop‘s most important concerns, i.e. to support the acquisition of knowledge and foster the ability to act. This applies to all citizens who are thereby enabled to get involved in all societal concerns in a more competent manner. However, it also applies to scientists whom we would like to motivate so that they deal quite consciously with civil society concerns and requests. 1 German Nature Conservation Prize Action Knowledge Preamble | 3 30 Years Bonn Science Shop Motivation History Funding For (now) thirty years the work of the Indignation about the fact that The Bonn Science Shop is a non-profit Bonn Science Shop has been dedicated scientists were doing their research organization, working on a cost- to societal challenges: the enormous in an ‚ivory tower‘ and citizens had covering but not profit-orientated consumption of land, the phasing out no benefit from it at all - that was the basis. -

Modules for Training of Science Shops Staff

ENHANCING THE RESPONSIBLE AND SUSTAINABLE EXPANSION OF THE SCIENCE SHOPS ECOSYSTEM IN EUROPE Modules for Training of Science Shops Staff Science Shops: the Basics This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No 741657. 2 This is an introductory training about Science Shops. It can be used as a stand-alone training session if only an overview into Science Shops is needed, or as a first module in the series of modules. Objectives In the area of expanding knowledge, after this module, participants will: ● Become familiar with the Science Shop concept, its benefits and relationship with public engagement and RRI ● Understand the principles of running a Science Shop and related challenges ● Have gained an overview of the steps to establish a Science Shop In the area of skills and attitudes they will: ● Strengthen their interest in furthering their knowledge and skills with regard to Science Shops ● Be interested in establishing a Science Shop at their institution ● Be able to plan the first steps to establish a Science Shop Session outline Methodology Material required Duration Total: 2 hr 30 min 1. Welcome Training agenda (printed) 5 min. 2. Personal introductions "Post-it” notes (different colours) 15 min. and initial evaluation 2. Sharing experiences Invited speakers or videos 60 min. (including Q&A and discussion) 3. Presentation - Projector & large screen 90 min. (including Q&A - Key messages and discussion) - PowerPoint presentation 4. Interactive exercise 30–40 min. © 2019 SciShops.eu | Horizon 2020 – SwafS-01-2016 | 741657 3 Description of methodologies Welcome The trainer welcomes participants, presents the session’s aims, distributes and comments briefly on the training agenda. -

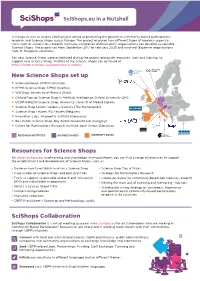

Factsheet: Scishops.Eu in a Nutshell

SciShops.eu in a Nutshell SciShops.eu was a Horizon 2020 project aimed at promoting the growth of community-based participatory research and Science Shops across Europe. The project explored how different types of research organisa- tions, such as universities, research institutes, companies and non-profit organisations can develop sustainable Science Shops. The project ran from September 2017 to February 2020 and involved 18 partner organisations from 13 European countries. Ten new Science Shops were established during the project alongside resources, tools and training to support new Science Shops. Profiles of the Science Shops can be found at https://www.scishops.eu/about/new-scishops/ New Science Shops set up ScienceShop.at, SYNYO (Austria) KPMG Science Shop, KPMG (Cyprus) WatShop, University of Brescia (Italy) Oxford Pop-up Science Shop in Artificial Intelligence, Oxford University (UK) UC3M-INAECU Science Shop, University Carlos III of Madrid (Spain) Science Shop Leiden, Leiden University (The Netherlands) Science Shop Leuven, KU Leuven (Belgium) Innovation Labs, Wuppertal Institute (Germany) Bay Zoltán Science Shop, Bay Zoltán Nonprofit Ltd (Hungary) Centre for Participatory Research, Institute Josef Stefan (Slovenia) Resources for Science Shops On www.scishops.eu, a networking and knowledge sharing platform, you can find a range of resources to support the establishment and development of Science Shops, such as: Guide on how to establish and run a Science Shop Science Shop Tips & Tricks Case studies of Science Shops and best practices