Hooded Plover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tasmania: Birds & Mammals 5 ½ -Day Tour

Bellbird Tours Pty Ltd PO Box 2008, BERRI SA 5343 AUSTRALIA Ph. 1800-BIRDING Ph. +61409 763172 www.bellbirdtours.com [email protected] Unique and unforgettable nature experiences! Tasmania: birds & mammals 5 ½ -day tour 15-20 Nov 2021 Australia’s mysterious island state is home to 13 Tasmanian Thornbill and Scrubtit, as well as the beautiful endemic birds as well as some unique mammal Swift Parrot. Iconic mammals include Tasmanian Devil, species. Our Tasmania: Birds & Mammals tour Platypus and Echidna. Add wonderful scenery, true showcases these wonderful birding and mammal wilderness, good food and excellent accommodation, often highlights in 5 ½ fabulous days. Bird species include located within the various wilderness areas we’ll be visiting, Forty-spotted Pardalote, Dusky Robin, 3 Honeyeaters, and you’ll realise this is one tour not to be missed! The tour Yellow Wattlebird, Tasmanian Native-Hen, Black commences and ends in Hobart, and visits Bruny Island, Mt Currawong, Green Rosella, Tasmanian Scrubwren, Wellington and Mt Field NP. Join us in 2021 for an unforgettable experience! Tour starts: Hobart, Tasmania Price: AU$3,799 all-inclusive (discounts available). Tour finishes: Hobart, Tasmania Leader: Andrew Hingston Scheduled departure & return dates: Trip reports and photos of previous tours: • 15-20 November 2021 http://www.bellbirdtours.com/reports Questions? Contact BELLBIRD BIRDING TOURS : READ ON FOR: • Freecall 1800-BIRDING • Further tour details • Daily itinerary • email [email protected] • Booking information Tour details: Tour starts & finishes: Starts and finishes in Hobart, Tasmania. Scheduled departure and return dates: Tour commences with dinner on 15 November 2021. Please arrive on or before 15 November. -

Biodiversity Summary: Port Phillip and Westernport, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Tasmania and the Orange-Bellied Parrot – Set Departure Trip Report

AUSTRALIA: TASMANIA AND THE ORANGE-BELLIED PARROT – SET DEPARTURE TRIP REPORT 22 – 27 OCTOBER 2018 By Andy Walker We enjoyed excellent views of several of the Critically Endangered (IUCN) Orange-bellied Parrots during the tour. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Australia: Tasmania and the Orange-bellied Parrot: October 2018 Overview This short Tasmania group tour commenced in the state capital Hobart on the 22nd of October 2018 and concluded back there on the 27th of October 2018. The tour focused on finding the state’s endemic birds as well as two breeding endemic species (both Critically Endangered [IUCN] parrots), and the tour is a great way to get accustomed to Australian birds and birding ahead of the longer East Coast tour. The tour included a couple of days birding in the Hobart environs, a day trip by light aircraft to the southwest of the state, and a couple of days on the picturesque and bird-rich Bruny Island. We found, and got very good views of, all twelve endemic birds of Tasmania, these being Forty- spotted Pardalote, Green Rosella, Tasmanian Nativehen, Scrubtit, Tasmanian Scrubwren, Dusky Robin, Strong-billed, Black-headed, and Yellow-throated Honeyeaters, Yellow Wattlebird, Tasmanian Thornbill, and Black Currawong, as well as the two Critically Endangered breeding endemic species (Orange-bellied Parrot and Swift Parrot), of which we also got excellent and prolonged views of a sizeable proportion of their global populations. Other highlights included Little Penguin, Hooded Dotterel, Freckled Duck, White-bellied Sea Eagle, Wedge-tailed Eagle, Grey Goshawk, Laughing Kookaburra, Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo, Blue-winged Parrot, Pink Robin, Flame Robin, Scarlet Robin, Striated Fieldwren, Southern Emu-wren, and Beautiful Firetail. -

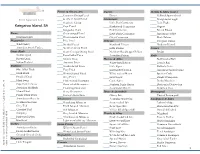

Bird Species Checklist

Petrels & Shearwaters Darters Hawks & Allies (cont.) Common Diving-Petrel Darter Collared Sparrowhawk Bird Species List Southern Giant Petrel Cormorants Wedge-tailed Eagle Southern Fulmar Little Pied Cormorant Little Eagle Kangaroo Island, SA Cape Petrel Black-faced Cormorant Osprey Kerguelen Petrel Pied Cormorant Brown Falcon Emus Great-winged Petrel Little Black Cormorant Australian Hobby Mainland Emu White-headed Petrel Great Cormorant Black Falcon Megapodes Blue Petrel Pelicans Peregrine Falcon Wild Turkey Mottled Petrel Fiordland Pelican Nankeen Kestrel Australian Brush Turkey Northern Giant Petrel Little Pelican Cranes Game Birds South Georgia Diving Petrel Northern Rockhopper Pelican Brolga Stubble Quail Broad-billed Prion Australian Pelican Rails Brown Quail Salvin's Prion Herons & Allies Buff-banded Rail Indian Peafowl Antarctic Prion White-faced Heron Lewin's Rail Wildfowl Slender-billed Prion Little Egret Baillon's Crake Blue-billed Duck Fairy Prion Eastern Reef Heron Australian Spotted Crake Musk Duck White-chinned Petrel White-necked Heron Spotless Crake Freckled Duck Grey Petrel Great Egret Purple Swamp-hen Black Swan Flesh-footed Shearwater Cattle Egret Dusky Moorhen Cape Barren Goose Short-tailed Shearwater Nankeen Night Heron Black-tailed Native-hen Australian Shelduck Fluttering Shearwater Australasian Bittern Common Coot Maned Duck Sooty Shearwater Ibises & Spoonbills Buttonquail Pacific Black Duck Hutton's Shearwater Glossy Ibis Painted Buttonquail Australasian Shoveler Albatrosses Australian White Ibis Sandpipers -

P0060-P0070.Pdf

POSSIBLE FUNCTIONS OF HEAD AND BREAST MARKINGS IN CHARADRIINAE WALTER D. GRAUL OTT (1966) proposed that many of the markings of shorebirds function C as disruptive coloration. Tinbergen (1953) and many other authors suggest that many avian plumage patterns have signal function and reinforce display movements. Ficken and Wilmot (1968) and Ficken, Matthiae, and Horwich (1971) suggested that eye lines in many vertebrates may enhance their vision and enable predaceous species to locate and capture prey more effectively. The latter authors further suggest that the head markings of the Semipalmated Plover (Chradrius semipuhatus) probably serve mainly a disruptive coloration function, although they point out that a given pattern may serve several functions. Bock (1958) tentatively speculated that in Charadriinae the breast bands and head markings act as disruptive marks, especially for the nesting bird, and some of the markings also reinforce aggressive and courtship displays. I have examined the literature concernin, v the Charadriinae in search of correlations that might provide suggestions on the relative importance of these possible functions in the subfamily as a whole, since many members of this group have complicated head and breast patterns and many have black lore lines. I have given special attention to (1) nest-site characteristics and (2) seasonal, sex, and age differences in coloration. I have also relied upon my 1969-72 observations on the Mountain Plover (C. montanus) in eastern Colorado for part of my conclusions. Jehl (1968) lists 37 species in the subfamily Charadriinae in his system of shorebird taxonomy and I have followed his scheme. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION A variety of head and breast markings is found in Charadriinae with 24 basic patterns (Fig. -

Hooded Plover Thinornis Rubricollis Husbandry Manual

Hooded Plover Thinornis rubricollis Husbandry Manual Image copyright © Paul Dodd Michael J Honeyman Charles Sturt University June 2015 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Introduction to the Species................................................................................ 5 1.2 History in Captivity........................................................................................... 5 1.3 Value of the Hooded Plover for education, conservation and research ............ 6 2 Taxonomy ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Nomenclature .................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Subspecies ......................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Recent Synonyms.............................................................................................. 7 2.4 Other common names ....................................................................................... 7 2.5 Discussion ......................................................................................................... 7 3 Natural History......................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Morphometrics .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.1 Measurements -

Fleurieu Birdwatch October 2006 … … … … … … … … … … Outings Here, the Peregrine Falcon Put on a Great Exhibition Onkaparinga Wetland for Us While We Had Lunch

fleurieu birdwatch Newsletter of Fleurieu Birdwatchers Inc October 2006 Meetings: Anglican Church Hall, cnr Crocker and Cadell Streets, Goolwa 7.30 pm 2nd Friday of odd months Outings: Meet 8.30 am. Bring lunch and a chair. See Diary Dates Contacts: Val Laird, phone 8555 5995 Judith Dyer, phone 8555 2736 42 Daniel Avenue, Goolwa 5214 30 Woodrow Way, Goolwa 5214 [email protected] [email protected] Website: users.bigpond.net.au/FleurieuBirdwatchers Newsletter: Verle Wood, 13 Marlin Terrace, Victor Harbor 5211; [email protected] s Saturday 2 December Breakup, Goolwa Barrage Meet in the barrage car park for bird walk at 4.00 pm followed by a Byo everything barbecue. s Saturday 7 October s Friday 12 January 2007 Mt Magnificent CP, Blackfellow’s Creek Twilight Walk, Jarnu Meet at the junction of Nangkita and Enterprise Meet at the Lions Park, Currency Creek, 7.00 pm. Roads, Nangkita. Remember the thermos/esky and nibbles for s Fri–Mon 27–30 October supper after the walk. Campout at Burra Details and maps page 6 s Friday 10 November Meeting A special treat! Speaker: Neil Cheshire Australia’s sub-Antarctic, s Sunday 12 November Heard Island and Southern Ocean sea birds Aldinga Scrub Meet at the park entrance, Cox Road, Aldinga. Member Neil Cheshire will share some unique sightings with us. s Wednesday 22 November And you won’t have to worry about Inman Estuary, Franklin Parade esplanade, the getting your sea-legs to see them! Bluff, Victor Harbor Meet at Barker Reserve, Bay Road, Victor Harbor, 7.30 pm Friday 10 November opposite Council Chambers. -

BIRD LIST NEW ZEALAND South Island – (31

AROUND THE WORLD – BIRD LIST NEW ZEALAND South Island – (31) North Island – (10) Yellow-eyed penguin North Island robin Blue penguin Saddleback White-faced heron Stitchbird (hihi) Black swan Eastern rosella South Island pied oystercatcher Banded rail Variable oystercatcher Pied shag New Zealand pigeon Welcome swallow Bellbird Banded dotterel Tui New Zealand pipit Australian magpie Paradise shelduck Tomtit Silvereye Blackbird Song thrush Chaffinch Yellow hammer Royal spoonbill New Zealand falcon New Zealand fantail Red-billed gull Black-backed gull Gray warbler Bar-tailed godwit Pied stilt Goldfinch Black shag Black-billed gull Spur-winged plover (masked lapwing) California quail Pukeko Common mynah Cook Strait Ferry – (5) Spotted shag Westland petrel Gannet Fluttering shearwater Buller’s albatross AUSTRALIA Queensland (QLD) – (33) Tasmania (TAS) – (11) Whimbrel Superb fairywren Willie wagtail Tasmanian nativehen (turbo chook) Magpie-lark Dusky moorhen White-breasted wood swallow Green rosella Red-tailed black cockatoo Yellow wattlebird (endemic) Sulphur-crested cockatoo Hooded dotterel (plover) Figbird Galah Rainbow lorikeet Crescent honeyeater Pied (Torresian) imperial pigeon Great cormorant Australian pelican Swamp harrier Greater sand plover Forest raven Pectoral sandpiper Peaceful dove Victoria (VIC) – (10) Australian brush-turkey Emu Australian (Torresian) crow Gray fantail Common noddy Pacific black duck Brown booby King parrot Australian white ibis Australian wood duck Straw-necked ibis Red wattlebird Magpie goose Bell miner Bridled -

Checklist Bruny Island Birds

Checklist of bird species found on Bruny Island INALA-BRUNY ISLAND PTY LTD Dr. Tonia Cochran Inala 320 Cloudy Bay Road Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia 7150 Phone: +61-3-6293-1217; Fax: +61-3-6293-1082 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.inalabruny.com.au 11th Edition April 2015 Total Species for Bruny Island: 150 Total species for Inala: 95 * indicates seen on the Inala property Tasmania's 12 Endemic Species (listed in the main checklist as well) 52 Tasmanian Native-hen* Tribonyx mortierii 82 Green Rosella* Platycercus caledonicus 100 Yellow-throated Honeyeater* Lichenostomus flavicollis 101 Strong-billed Honeyeater* Melithreptus validirostris 102 Black-headed Honeyeater* Melithreptus affinis 104 Yellow Wattlebird* Anthochaera paradoxa 111 Forty-spotted Pardalote* Pardalotus quadragintus 113 Scrubtit* Acanthornis magna 115 Tasmanian Scrubwren* Sericornis humilis 117 Tasmanian Thornbill* Acanthiza ewingii 121 Black Currawong* Strepera fuliginosa 134 Dusky Robin* Melanodryas vittata Species Scientific Name Galliformes 1 Brown Quail* Coturnix ypsilophora Anseriformes 2 Cape Barren Goose (rare vagrant to Bruny) Cereopsis novaehollandiae 3 Black Swan* Cygnus atratus 4 Australian Shelduck Tadorna tadornoides 5 Maned Duck (Aust. Wood Duck)* Chenonetta jubata 6 Mallard (introduced) Anas platyrhynchos 7 Pacific Black Duck* (partial migrant) Anas superciliosa 8 Australasian Shoveler Anas rhynchotis 9 Grey Teal* (partial migrant) Anas gracilis 10 Chestnut Teal* (partial migrant) Anas castanea 11 Musk Duck Biziura lobata Sphenisciformes -

Word About the Hood

Word about the Hood Biannual newsletter of BirdLife Australia’s Beach-nesting Birds Program Edition 15 – June 2016 UPDATE FROM THE BEACH-NESTING BIRDS TEAM Source: Glenn Ehmke Renée Mead and Meghan Cullen, Beach-nesting birds interim Managers! The birds started on time this season (August), and had many of us off guard at how quickly the season took off! Normally there’s a spattering of nests recorded along the coast, and then it really starts to pick up and get into the swing of things in late September (depending on the region). But the birds started in August, and then kept going, and going, and going, with the last fledgling recorded in Belfast Coastal Reserve in Far west Victoria in mid April. The Beach-nesting Birds team have been busy delivering and finalising grants, and supporting our diverse Friends of the Hooded Plover groups across southern east Australia. We’ve been busy on Eyre Peninsula, Samphire Coast, Fleurieu Peninsula in South Australia, in Victoria we’ve been all along the Great Ocean Road, Mornington Peninsula, Bass Coast – and everywhere in between! Late in January, Coast and Marine Program Manager, Dr. Grainne Maguire went on maternity leave! This was a bit sudden as itty bitty little Elara was born early. Grainne would like to pass on her disappointment at not getting to say a temporary goodbye to everyone and apologises for leaving some things unfinished. After a long four months, Elara is out of hospital. She is a well loved member of the BNB team, and little sister to Kai! We want to congratulate Grainne on -

Large Flock of Sanderling at Port Fairy, Victoria by MICHAEL J

Vol. 6 JUNE 15, 1976 No.6 Large Flock of Sanderling at Port Fairy, Victoria By MICHAEL J. CARTER, Frankston, GRACIE BOWKER, Port Fairy, and ANDREW C. ISLES, Warrnambool, Victoria. About mid September 1974, Gracie Bowker discovered a flock of between 200 and 300 Sanderling, Calidris alba, on a beach about 5 km west of Port Fairy in Western Victoria. Sanderling normally summer on this beach, known locally as the Little River Beach, but a flock of this size was unprecedented. Large numbers of Sanderling continued to frequent this beach for the next five and a half months, the highest counts being 320 on October 25, 1974, (A.C.I.), and 290 on January 24, 1975, (M.J.C.). None were there on March 1, 1975, (A.C.I.). However, on March 7, 1975, Andrew C. Isles discovered a gathering of at least 400 Sanderling on the kelp beach between The Cutting and Rogers Rocks over 10 km east of Port Fairy. On March 9, the flock had apparently moved 4 km west to Sisters Point, where 250 were found grouped behind clumps of kelp on the sandspit. They were still present on March 12 when the flock was estimated to exceed 380 (G.B.). Sanderlings seen subsequently were 16 between The Cutting and Killarney beach on March 31 and 30 at Little River and 44 at Sisters Point on April6, 1975. These gatherings, we believe, are the largest so far reported in Australia. While the Sanderling is normally regarded as a widespread summeP migrant to Australian beaches it is not normally con sidered common. -

BORR Northern and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment (Biota 2019A) – Part 3 (Part 7 of 7) BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna

APPENDIX E BORR Northern and Central Section Targeted Fauna Assessment (Biota 2019a) – Part 3 (part 7 of 7) BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna 6.0 Conservation Significant Species This section provides an assessment of the likelihood of occurrence of the target species and other conservation significant vertebrate fauna species returned from the desktop review; that is, those species protected by the EPBC Act, BC Act or listed as DBCA Priority species. Appendix 1 details categories of conservation significance recognised under these three frameworks. As detailed in Section 4.2, the assessment of likelihood of occurrence for each species has been made based on availability of suitable habitat, whether it is core or secondary, as well as records of the species during the current or past studies included in the desktop review. Table 6.1 details the likelihood assessment for each conservation significant species. For those species recorded or assessed as having the potential to occur within the study area, further species information is provided in Sections 6.1 and 6.2. 72 Cube:Current:1406a (BORR Alternate Alignments North and Central):Documents:1406a Northern and Central Fauna Rev0.docx BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna This page is intentionally left blank. Cube:Current:1406a (BORR Alternate Alignments North and Central):Documents:1406a Northern and Central Fauna Rev0.docx 73 BORR Northern and Central Section Fauna Table 6.1: Conservation significant fauna returned from the desktop review and their likelihood of occurrence within the study area. ) ) ) 2014 2013 ( ( Marri/Eucalyp Melaleuca 2015 ( Listing ap tus in woodland and M 2012) No.