In Southeast Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory and Cataloging of Sport Fish and Sport Fish Waters

Volume 14 Study G-I Study A-I Job R-IV-D STATE OF ALASKA William A. Egan, Governor Annual Progress Reports for INVENTORY AND CATALOGING INVESTIGATIONS OF PUBLIC FISHING ACCESS AND AQUATIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS DISSEMINATION OF INFO~TION COLLECTED ON DOLLY VARDEN by F. Van Hulle, J. B. Murray, C. J. Kalb D. L. Siedelman, P. B. Cunningham T. W. Trent,T!. A. Stefanich, D. L. Bill R. H. Armstrong ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME James W. Brooks, Comrnassioner DIVISION OF SPORT FISH Rupert E. Andrews, Director Howard E. Metsker, Coordinator Volume 14 Study G-I Job No. G--I-B RESEARCH PROJECT SEGMENT State: Alaska Name: Sport Fish Investigations of Alaska. Project No: F-9-5 Study Title: Inventory and Cataloging. Study No: G-I Job Title: Inventory and Cataloging of the Sport Fish and Sport Fish Waters in Southwest Alaska. Job: G-I-B Period Covered: July I, 1972 thru June 30. 1973. ABSTRACT Physical and chemical water properties and/or volumetric surveys were conducted on five lakes prior to rehabilitation. Abercrombie Lake. Lake Genevieve. and Margaret Lake were treated with liquid rotenone at 1.5 ppm. Three lakes on Adak Island and 29 on Kodiak Island were sampled with gillnets to determine species. relative abundance. and size of native and stocked fish. Lakes sampled for dissolved oxygen and pH in early March showed favorable conditions for fish survival. Ice depth varied from 22 to 30 inches. The Buskin River Dolly Varden, Salvelinus malma, outmigration commenced about May 15 and ended approximately May 31. May creel census indicated a harvest rate of 1.9 fish per hour. -

Karluk River Steelhead Population Assessment Operational Plan. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Regional Operational Plan ROP.SF.2A.2018.03, Anchorage

Regional Operational Plan SF.2A.2018.03 Karluk River Steelhead Population Assessment Operational Plan, 2018-2019 by Tyler B. Polum and Adam Reimer April 2018 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. expected value E nautical mile nmi Corporation Corp. -

Inventory and Cataloging of the Sport Fish and Sport Fish Waters in Southwestern Alaska

Volume 22 STATE OF ALASKA Jq S. Banan#lnd, Gotfernor Annual Performance Report for INVENTORY AND CATALOGING OF THE SPORT FISH AND SPORT FISH WATERS IN SOUTHWESTERN ALASKA Frmjc Vm HuZZe und John 3. klrry ALASKA PEPARTHENT OF FISH AND GAME Ronald 0, Skoog, Codssioner SPORT FISH PZVTSfON Rupert E, Andrews, Dimctor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We greatfully acknowledge the assistaace and cooperation of the Kodiak Commercial Fisheries Division, United States Forest Service and the National Harine Fisheries Service. TABLE OF CONTENTS STUDY NO . G-I lNVENTORY AM) CATALOGING Job No . G-I-B Inventory and Cataloging of the Sport Fish and Sport Fish Waters in Southwestern Alaska By: Frank Van Hulle and John B . Murray Abstract ................................. 1 Background ............................... 2 Recommendations . ..'.. ....................... 4 Objectives ............................... 4 TechniquesUsed ............................ 4 Lake and Stream Surveys' ....................... 6 Abercrombie Lake ........................... 11 Bull Lake .............................. 11 Lilly Pond ............................. Long Lake .............................. 11 Lupine Lake ............................. 12 Pony Lake .............................. 12 SouthernLake ............................ 12 Delphin Bay Lake #I3566 ....................... 13 Roadside Stream Flows and Temperatures ................ 13 Lake Rose Tead ............................ 16 Sport Fish Harvest Estimates ..................... 22 Assessment and Inventory of Anadromous Fish Populations -

Kodiak Island Is a Part of an Archipelago of Islands Including Afognak, Shuyak, and 20 Smaller Islands

Southcentral Region Southcentral Alaska Alaska Department of Fish and Game Recreational Fishing Series Division of Sport Fish Kodiak About Kodiak Kodiak Island is a part of an archipelago of islands including Afognak, Shuyak, and 20 smaller islands. Kodiak Island is the second-largest in the United States; only the big island of Hawaii is larger. The Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge covers two-thirds of Kodiak Island. The State of Alaska, various Alaska Native corporations, and private individuals own the remainder. The city of Kodiak is 250 air miles southwest of Anchorage. Two airlines, Alaska Airlines (1-800-252-7522) and ERA Airlines (1-800-866-8394), have daily flights from Anchorage. The Alaska Marine Highway system offers a passenger and vehicle ferry from Homer and Seward to Kodiak four times a week during the fishing season (1-800-642- 0066). About 11,000 people live along the Kodiak Island’s streams and lakes offer easily accessible and remote fishing Kodiak road system, and 14,000 opportunities for salmon, steelhead, Dolly Varden (above) and more. (ADF&G) visitors arrive every year. Available services include approximately 70 Regulations on the Road System differ slightly from charter operators, 33 remote lodges, six air taxi services, the Remote Area, so check the regulations book carefully. 12 state and federal public-use cabins, 10 private remote There are 75 miles of paved and hard-packed gravel roads cabins for rent, five hotels and motels, 30 bed-and- that cross 10 significant streams and provide access to 18 breakfasts, three sporting goods stores, and other amenities stocked lakes. -

A Fishing Experience Like No Other

A fishing experience like no other. experience wild alaska, one cast at a time Salmon - Steelhead - Trout Get hooked on the karluk Kodiak’s Green Goddess Located in the heart of the 1.9-million-acre Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, Karluk Lake is the most productive watershed on Kodiak Island, home to one of the highest densities of bears in the world. Our fi shing program is designed to provide our guests with an opportunity to fi sh the pristine waters that make up the Karluk Watershed, including all of the tributaries that fl ow into the lake. Karluk Lake forms the headwaters of the Karluk River, a winding 22-mile (35 km) system that supports diverse and abundant fi sh runs. Legendary for chinook salmon and steelhead trout, the Karluk also supports other salmon species (sockeye, coho, chum and pink) as well as Dolly Varden, arctic char and rainbow trout. “the kodiak brown bear center and its exceptional lodging stand alone as luxury in the middle of kodiak island. truly, heaven on earth!” john shier, producer/cinematographer The prime season on the Karluk for steelhead and char is in late September and October, providing our clients with an extended fi shing season. Karluk Lake offers over 30 miles of shoreline with countless tributaries creating some of the highest salmon concentrations on Kodiak. Our clients will experience a variety of conditions that allow them to use different weight rods, leaders, tippets, and fl ies. Whether you’re targeting the rapid, shallow river current where steelhead can be found or the deep holes where the chinook and coho like to congregate, our experienced guides can help educate you in the best tactics to be successful. -

Preliminary Environmental Assessment for Proposed Kodiak Microwave Systems, LLC Telecommunications Project

Preliminary Environmental Assessment for Proposed Kodiak Microwave Systems, LLC Telecommunications Project U.S. Fish United States Fish and Wildlife Service Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge 1390 Buskin River Road Kodiak, AK 9961 May 2016 Photo by Yathin Krishnappa U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Preliminary Environmental Assessment for Proposed Kodiak Microwave Systems, LLC Telecommunications Project, Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, Kodiak Island, Alaska This preliminary Environmental Assessment (EA) was prepared in accordance with the US Department of Interior Departmental Manual 516, and is in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (and subsequent amendments) (P.L. 91-190) and the Council on Environmental Quality Regulations dated November 1978 (40 CFR 1500-1508). This EA serves as a public document to briefly provide sufficient evidence and analysis for determining the need to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement or a Finding of No Significant Impact. This EA concisely describes the need for the proposal, a reasonable range of alternatives, and potential environmental impacts of the proposed action and the alternatives. The EA provides a list of the agencies and persons consulted during EA preparation. Comments may be sent to Tracy Fischbach, Natural Resources Planner, by: Email: [email protected]; or, Mail: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road, MS 231 Anchorage, AK 99503 ATTN: Tracy Fischbach Call Tracy Fischbach at (907)786-3369, if you have questions about the EA directly or about how to -

Kodiak About Kodiak Kodiak Island Is a Part of an Archipelago of Islands That Includes Afognak Island, Shuyak Island, and 20 Smaller Islands

Southcentral Region Alaska Department of Fish and Game Southcentral Alaska Division of Sport Fish Recreational Fishing Series Kodiak About Kodiak Kodiak Island is a part of an archipelago of islands that includes Afognak Island, Shuyak Island, and 20 smaller islands. The island is the second-largest in the United States, with the big island of Hawaii the only larger island. The Ko- diak National Wildlife Refuge covers 2/3 of Kodiak Island. The State of Alaska, various Alaska Native corporations, and private individuals own the remainder. The City of Kodiak is 250 air miles southwest of Anchor- age. Two airlines, Alaska Airlines (1-800-252-7522) and ERA Airlines (1-800-866-8394), have daily fl ights from Anchorage (depending on weather). The Alaska Marine Highway system offers a passenger and vehicle ferry from Homer and Seward to Kodiak four times a week during the A Kodiak Island king salmon. fi shing season (1-800-642-0066). About 11,000 people live along the Kodiak Road System, also includes all salt waters bordering the Road System and 14,000 visitors arrive every year. Available services within one mile of Spruce and Kodiak islands. include 70 charter operators, 33 remote lodges, 6 air taxis, Regulations on the Road System differ slightly from 12 state and federal public use cabins, 10 private remote the Remote Area, so check the Kodiak regulation book cabins for rent, 5 hotels and motels, 30 bed and breakfasts, carefully. 4 sporting good stores, as well as all the other amenities There are 70 miles of paved and hard-packed gravel usually found in a community this size. -

Kodiak Management Area Weir Descriptions and Salmon Escapement Report, 2013

Fishery Management Report No. 14-11 Kodiak Management Area Weir Descriptions and Salmon Escapement Report, 2013 by Brad A. Fuerst March 2014 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. expected value E nautical mile nmi Corporation Corp. -

3.4. History of Karluk Lake Fishery

KARLUK LAKE NUTRIENT ENRICHMENT Preliminary Environmental Assessment and Section 810 Evaluation Kodiak Island, Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge Kodiak, Alaska Karluk Lake Nutrient Enrichment EA and ANILCA Section 810 Evaluation Karluk Lake Nutrient Enrichment EA and ANILCA Section 810 Evaluation KARLUK LAKE NUTRIENT ENRICHMENT PRELIMINARY ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT AND ANILCA SECTION 810 EVALUATION Prepared by SWCA Environmental Consultants 1205 E. International Airport Road, Suite 103 Anchorage, Alaska 99518 (907) 279-7922 Prepared for Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge 1390 Buskin River Road Kodiak, Alaska 99615 (907) 487-2600 December 2014 Karluk Lake Nutrient Enrichment EA and ANILCA Section 810 Evaluation Karluk Lake Nutrient Enrichment EA and ANILCA Section 810 Evaluation CONTENTS 1. Purpose and Need for Action ............................................................................................ 1 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Purpose and Need for Action ........................................................................................................ 1 1.3. Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3.1. Proposed Project History ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3.2. Summary of the Karluk Sockeye Salmon Fishery ............................................................... -

Sockeye Salmon

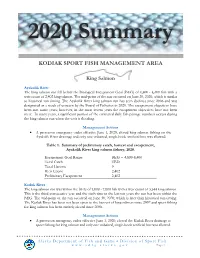

2020 Summary KODIAK SPORT FISH MANAGEMENT AREA King Salmon Ayakulik River The king salmon run fell below the Biological Escapement Goal (BEG) of 4,800 - 8,400 fish with a weir count of 2,402 king salmon. The mid-point of the run occurred on June 20, 2020, which is similar to historical run timing. The Ayakulik River king salmon run has seen declines since 2006 and was designated as a stock of concern by the Board of Fisheries in 2020. The escapement objectives have been met some years; however, in the most recent years the escapement objectives have not been meet. In many years, a significant portion of the estimated daily fish passage numbers occurs during the king salmon run when the weir is flooding. Management Actions • A preseason emergency order effective June 1, 2020, closed king salmon fishing on the Ayakulik River drainage and only one unbaited, single-hook artificial lure was allowed. Table 1. Summary of preliminary catch, harvest and escapement, Ayakulik River king salmon fishery, 2020. Escapement Goal Range BEG = 4,800-8,400 Total Catch TBD Total Harvest 0 Weir Count 2,402 Preliminary Escapement 2,402 Karluk River The king salmon run was within the BEG of 3,000 - 7,000 fish with a weir count of 3,344 king salmon. This is the third consecutive year and the sixth time in the last ten years the run has been within the BEG. The mid-point of the run occurred on June 30, 2020, which is later than historical run-timing. The Karluk River has been not been open to the harvest of king salmon since 2007 and sport fishing for king salmon has been entirely closed since 2008. -

Assessment of the 1994 Return of Steelhead to the Karluk River, Alaska

Fishery Data Series No. 95-41 Assessment of the 1994 Return of Steelhead to the Karluk River, Alaska bY Robert N. Begich December 1995 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish FISHERY DATA SERIES NO. 95-41 ASSESSMENT OF THE 1994 RETURN OF STEELHEAD TO THE KARLUK RIVER, ALASKA Robert N. Begich Division ofsport Fish, Kodiak Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish, Research and Technical Services 333 Raspberry Road, Anchorage, Alaska, 995 18-1599 December 1995 This investigation was partially financed by the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act (16 U.S.C. 777-777K) under Project F-10-10, Job No. R-2-7. The Fishery Data Series was established in 1987 for the publication of technically-oriented results for a single project or group of closely related projects. Fishery Data Series reports are intended for fishery and other technical professionals. Distribution is to state and local publication distribution centers, libraries and individuals and, on request, to other libraries, agencies, and individuals. This publication has undergone editorial and peer review. Robert N. Begich Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Sport Fish, 21 I Mission Road, Kodiak, Alaska, 99615-6399, USA This document should be cited as: Begich, Robert N. 1995. Assessment of the 1994 return of steelhead to the Karluk River, Alaska. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Fishery Data Series No. 95-41, Anchorage. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game administers all programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, national origin, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. -

Synopsis of Biological Data on the Chum Salmon Oncorhynchus Keta

FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 41 BCF/S 41 SAST Chum ea1mon - 1,23(O1),009,03 SYNOPSIS OF BlOLOGîCAL DATA ON THE CHUM SALMON,, Oncorhy.nchus kéta (Wàîba urn) 1792 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE BUREAU OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES Circular 315 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Walter J. Hickel, Secretary Russell E. Train, Under Secretary Leslie L. Glasgow, Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources Charles H. Meacham, Comlni8eioner, U.S. FISH AND WILDUJFE SERVICE Philip M. Roedel, Director, BUREAU OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES Synopsis of Biological Data onthe Chum Salmon, Oncorhynchus keta (Walbaum) 1792 By RICHARD G. BAKKALA FAO Species Synopsis No, 41 Circular 315 Washington, D.C. March 1970 CONTENTS Pag e Introduction i Identity i 1.1 Nomenclature i 1.2 Taxonomy i 1.3 Morphology 5 2 Distribution 8 2.1Total areas 8 2.2 Differential distribution 9 2.3 Determinants of distribution 10 2.4 Hybridization il 3 Bionomics and life history 12 3.1 Reproduction 12 3.2 Preadult phase 24 3.3 Adult phase 28 3.4 Nutrition and growth ¿9 3.5 Behavior 39 4 Population 42 4.1 Structure 42 4.2 Abundance and density (of population) 46 4.3 Natality and recruitment 50 4.4 Mortality and morbidity 51 4.5 Dynamics of population 57 4.6 Population in community and ecosystem 59 5 Fishery 60 5.1 Fishing equipment 60 5.2 Fishing areas 64 5.3 Fishing seasons 65 5.4 Fishing operations and results 65 6 Protection and management .